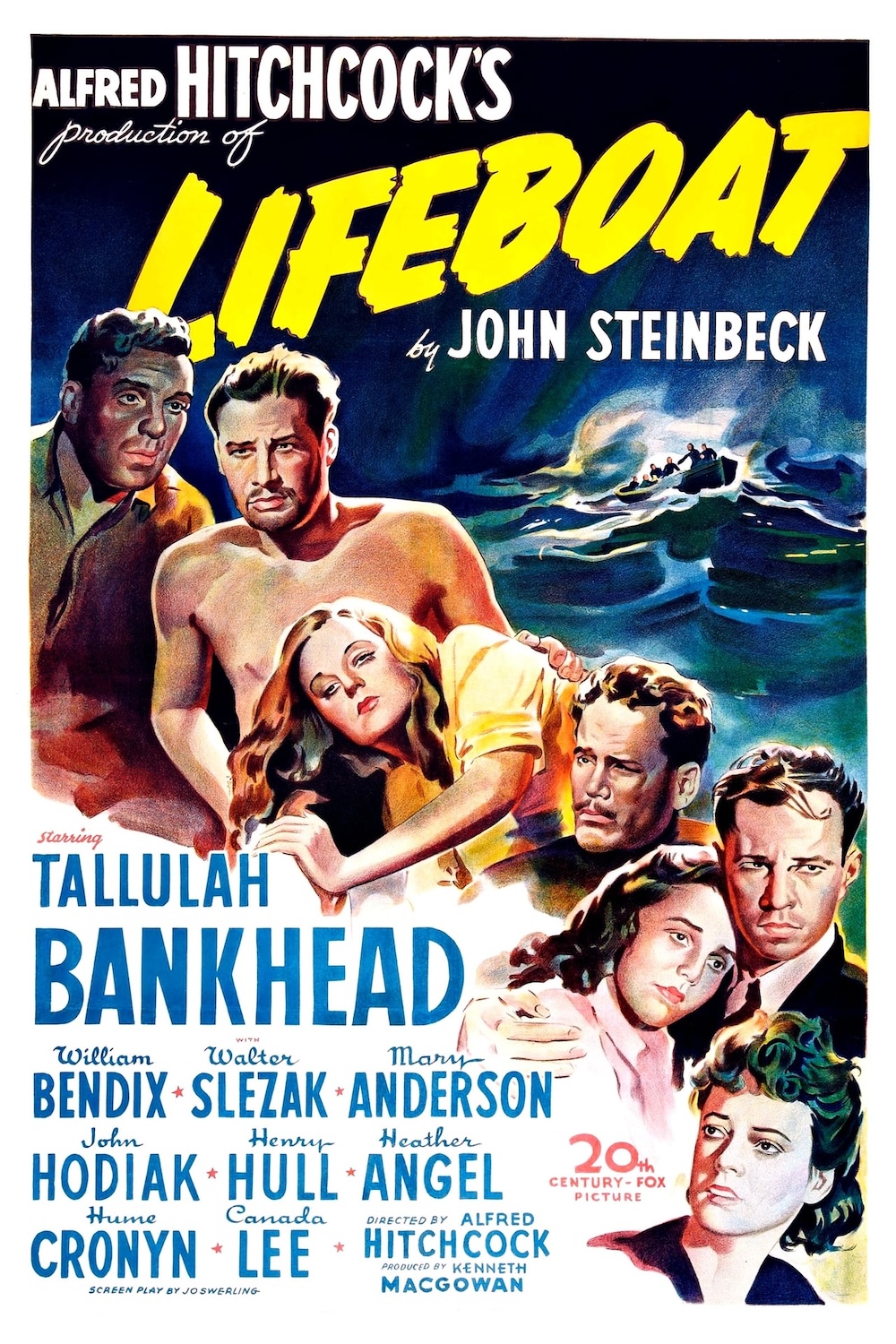

LIFEBOAT (1944)

Several survivors of a torpedoed merchant ship in WWII find themselves in the same lifeboat with one of the crew members of the U-boat that sank them.

Several survivors of a torpedoed merchant ship in WWII find themselves in the same lifeboat with one of the crew members of the U-boat that sank them.

The immense, unfeeling expanse of the ocean has often inspired stories of desperation and hope. It cannot be bargained with, cajoled, or placated. Exposure to sheer weather conditions of blinding sun and frigid cold ensures that the human body is always pushed to its extreme. And the thirst—don’t forget about the maddening thirst.

It’s 1944. A passenger vessel crossing the Atlantic is torpedoed. Sunk by a Nazi U-Boat, the wreckage sinks into the vast, watery deep. However, though the aggressor in the conflict, the German submarine could not escape unscathed and is destroyed in combat. Only a few make it out alive and swim to a nearby lifeboat. As debris and detritus litter the ocean around them, survivors climb aboard and begin to acquaint themselves. But when a German is pulled onto their raft, a suspenseful moral dilemma soon follows…

Though a lesser-known work within Hitchcock’s oeuvre, Lifeboat proves just as compelling a story as any of his acknowledged masterpieces. This claustrophobic tale of human survival throws Hitchcock’s masterful direction into sharp relief, showcasing his signature skills: sublime staging, deft camerawork, and impactful performances, all propelled by impeccable pacing. Beyond technical brilliance, Hitchcock weaves a profound exploration of tribalism and universal values into the narrative, crafting a film that resonates with both raw emotion and fraught tension.

From the opening shot, Hitchcock imparts a sense of the abyss. As the monumental passenger vessel vanishes without a trace, its funnel still spewing smoke in defiance of its watery demise, we shrink in the face of such immensity. In this single image, he establishes a recurring theme—the unfeeling magnitude of nature. Everything is lost in the ocean: our stability, our sanity, and if one is not wise enough to cling to it, our hope.

Disoriented in the middle of the Atlantic, the crew argue over the direction in which they should sail. Juxtaposed against the vastness of their predicament, their human concerns seem impossibly trivial. The fact that Willi (Walter Slezan) is a Nazi soldier means he can’t be believed, despite the fact he’s the only one who can navigate their surroundings. Distrust threatens to doom them all to starvation. Amid a turbulent storm, the Nazi scolds his British and American counterparts for their short-sightedness: “You fools! Stop thinking of yourselves! Think of the boat!”

This single line of dialogue seems to hint at the narcissism and self-righteousness bred by demagoguery within a disillusioned citizenry, echoing the populism that gripped Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy. Instead of confronting the mounting problems staring them in the face, these individuals, consumed by desperation, turn inward, lashing out at one another while the true storm, a sinister omen of their demise, steadily gathers strength. The realisation of their folly dawns tragically late, their eyes opening to the truth of how, by blindly handing their trust to an untrustworthy leader, they have unwittingly steered themselves into oblivion.

On a broader scale, the play serves as a stark commentary on how the myopia nurtured by nationalism can sink an entire nation. Just as the focus of those on the raft should have been on the collective effort to stay afloat, rather than internal squabbles, so too should our global gaze extend beyond individual concerns to encompass the precarious state of our shared vessel, lest we too succumb to the treacherous waters of apathy and division. The raft becomes a poignant microcosm of our own global lack of collective prudence, serving as a haunting reminder of the dangers we face when we lose sight of the bigger picture.

Hitchcock’s first chamber drama finds an incredibly engaging setting in the confines of a lifeboat dwarfed by swirling waves. The bitter irony of how one is gripped by claustrophobia amidst the vast ocean isn’t lost on him. He masterfully displays his talent for crafting sustained tension, pacing, and plot developments, proving that even a cramped setting can’t stifle his storytelling prowess.

Often, the limitations of a single setting can become a hurdle in chamber dramas. With no external influences to stir the pot, it can be challenging to introduce dramatic revelations or build compelling suspense. However, this was never an issue for Alfred Hitchcock. He confined his characters to a single location three times throughout his career, each time crafting brilliant drama. In Rope (1948) he arguably created the purest chamber drama ever made. In 1954, he delivered claustrophobic tension twice: first in Dial M for Murder and again in Rear Window, the latter of which I consider to be his masterpiece.

What sets Lifeboat apart from Hitchcock’s other chamber dramas is his masterful use of confined space to generate tension within his characters. This proves that the maestro truly could squeeze water from a stone.

While on the subject of tension, it is worth pointing out how the premise of the story itself is inherently suspenseful: within small confines, a murderer sits among them—and everyone knows who it is. Yet there are rules to be followed: as a prisoner of war, they cannot simply toss him out of the boat. This sets the stage for a potent brew of suspicion and subterfuge. John Kovac (John Hodiak), exuding a constant distrustful edge, seems capable of erupting into malice at any moment. Our Nazi passenger isn’t above suspicion either, his nonchalant facade leaving us unsure whether it masks sinister intentions or is genuine indifference. This uncertainty, the inability to discern true motives, gnaws at the passengers, weaving a constant shroud of tension and doubt.

Hitchcock’s genius is on display here. He never shows us enough to confirm our suspicions, nor does he allow us adequate room to relax. He proves once again how he has a shrewd understanding of the power of images, as well as a keen awareness regarding how to convey information as economically as possible. Because of this, a man holding a compass becomes extraordinarily suspenseful and a boot placed emphatically on a bench is dolefully shocking. Hands clasping the side of a boat introduce a character with immediate and foreboding significance, while a conversation in German becomes agonisingly thrilling as we eagerly await the translation.

Hitchcock amplifies all of these traits through his technical mastery of the cinematic medium. Foremost, his understanding of staging within confined spaces not only heightens tension but also maximizes the performances of his skilled actors. His expert use of the dolly zoom allows the camera to move seamlessly, never feeling cumbersome. This is crucial, as cluttered or hectic staging can induce audience apathy; if viewers struggle to see the characters, they’ll struggle to identify with them. Hitchcock avoids such a problem by ensuring every character who requires a close-up gets one right on cue.

To achieve this level of control, the production team crafted four distinct boats, enabling them to capture every desired camera angle. Two boats were fully functional lifeboats, while the other two were bisected: one lengthwise, the other crosswise. This meticulous preparation demonstrates one of the director’s exceptional skills as a filmmaker. By physically moving us through the scene, he treats us as a silent tenth character, placing us directly aboard the claustrophobic ship alongside the protagonists.

Glen MacWilliams, the film’s cinematographer, shines brightly, enriching the story with his evocative photography. This is evident early on in the film as he elevates intimate moments with exquisite lighting. A woman sleeps with her arms extended, cradling a baby who is no longer there. As she realises, her face darkens, symbolising the pall that has spread over their boat. As they say, a prayer for the small, lifeless child cast adrift, the morning sun illuminates their grave countenances. A new day is upon them; though it has begun in mourning, the possibility of hope whispers to them still. It’s always starkly apparent how intuitive Hitchcock is in communicating through a visual medium—that the virtuoso got his start in the silent film era can be seen.

However, dialogue in Hitchcock’s films has never been a low point either. In Lifeboat, it’s both witty and emotional, managing to be poignant and irreverent in equal measure. Based on John Steinbeck’s short story, one can see the depth of character in the performances, which never become too theatrical despite the sensational subject matter. The showings are all measured and convey the enormity of their predicament believably. Faced with the prospect of losing his leg, Gus (William Bendix) holds both trepidation and scorn in his eyes, though he manages to muster the strength to put on a forced smile: “Give us a kiss,” he playfully demands of Connie Porter (Tallulah Bankhead).

And she does, unhesitant and unbashful. While the film may be a masterclass in film form and technique, its enduring power resides in the depths of human emotion. In their struggle against both the elements and themselves, a profound human story emerges. A parable reveals itself about the importance of sticking together, of finding fortitude in unity, of facing adversity with a smile. Though Hitchcock’s films are traditionally plot-driven, Lifeboat is, at its foundation, built on the backs of its characters. Each soul aboard contributes to the morale, forging a lifeline in the face of uncertain survival.

Everything that unfolds in that small lifeboat encapsulates not only the horrors of war but the horrors of human depravity. War, after all, is merely a manifestation of our most base impulses: aggression, fear, and the catastrophic desire for control. Plunged into the depths of despair, hunger, and thirst, caustic vitriol and animalistic violence ensue. However, the story also showcases the human capacity for love, kindness, understanding, and intimacy. As Connie assures her newfound partner: “Dying together is even more personal than living together.” In the most extreme of circumstances, we find out who we really are—as well as who we can be.

USA | 1944 | 97 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • GERMAN • FRENCH

director: Alfred Hitchcock

writer: Jo Swerling (story by John Steinbeck).

starring: Tallulah Bankhead, William Bendix, Walter Slezak, Mary Anderson, John Hodiak, Henry Hull, Heather Angel, Hume Cronyn & Canada Lee.