Karloff: Universal Terror (1937-1952)

Eureka reissues three Boris Karloff movies from the late-1930s to the early-1950s: Night Key, The Climax, and The Black Castle.

Eureka reissues three Boris Karloff movies from the late-1930s to the early-1950s: Night Key, The Climax, and The Black Castle.

Expecting actual terror from this trio of Boris Karloff vehicles for Universal Pictures is a little over-optimistic. Night Key (1937) isn’t a horror at all, though it’s the best of the three, and of the other two only The Climax (1944) achieves the uncanny, very briefly.

But, while none of them will be hailed as neglected masterpieces, Night Key and The Climax are certainly watchable. And taken together, all three movies illustrate well the kind of production-line fare the studio system was churning out in the mid-20th-century, which we can easily forget when we concentrate solely on the classics.

As so often with such films, they largely work by varying the plots of films that preceded them and by reassembling parts from disparate sources. Thus, for example, Night Key zeroes in on one aspect of modern life—the electrical burglar alarm system—and rather earnestly explains its wonders before using it as the hook for a cops-and-robbers drama.

It’s a relatively disciplined film, trying to push the boundaries of a well-established genre without completely breaking them —among its novelties, the cops aren’t actual cops and the central robber doesn’t want to really steal anything, but it still has recognisable resemblances to more conventional examples.

The Black Castle (1952) is more Catholic in its grab-bag approach to the premise, plotting, and previous releases, mashing up elements of Romeo and Juliet, The Most Dangerous Game (1932), the 19th-century fear of being buried alive (as evoked by Poe and others), the evil-nobleman-in-his-remote-fastness trope, perhaps a little from The Island of Doctor Moreau, and more.

The Climax, meanwhile, was conceived as a direct follow-up to The Phantom of the Opera (1943) and retains strong affinities with it, while also bringing in the reliable B-picture standby of hypnotism.

Boris Karloff is in all of them: not doing much more in The Black Castle than helping to turn decidedly creaky plot wheels, but in fine evil form as the obsessed doctor-hypnotist in The Climax, and very sympathetic as a hard-done-by inventor and loving father in Night Key. At the same time as providing a taste of average fare as seen by many cinemagoers week to week in the late-1930s to early-1950s, then, Universal Terror also provides a reminder of just how versatile this actor—now associated almost entirely with horror—could be.

An inventor swears revenge on the company that cheated him and is dragged into a world of crime.

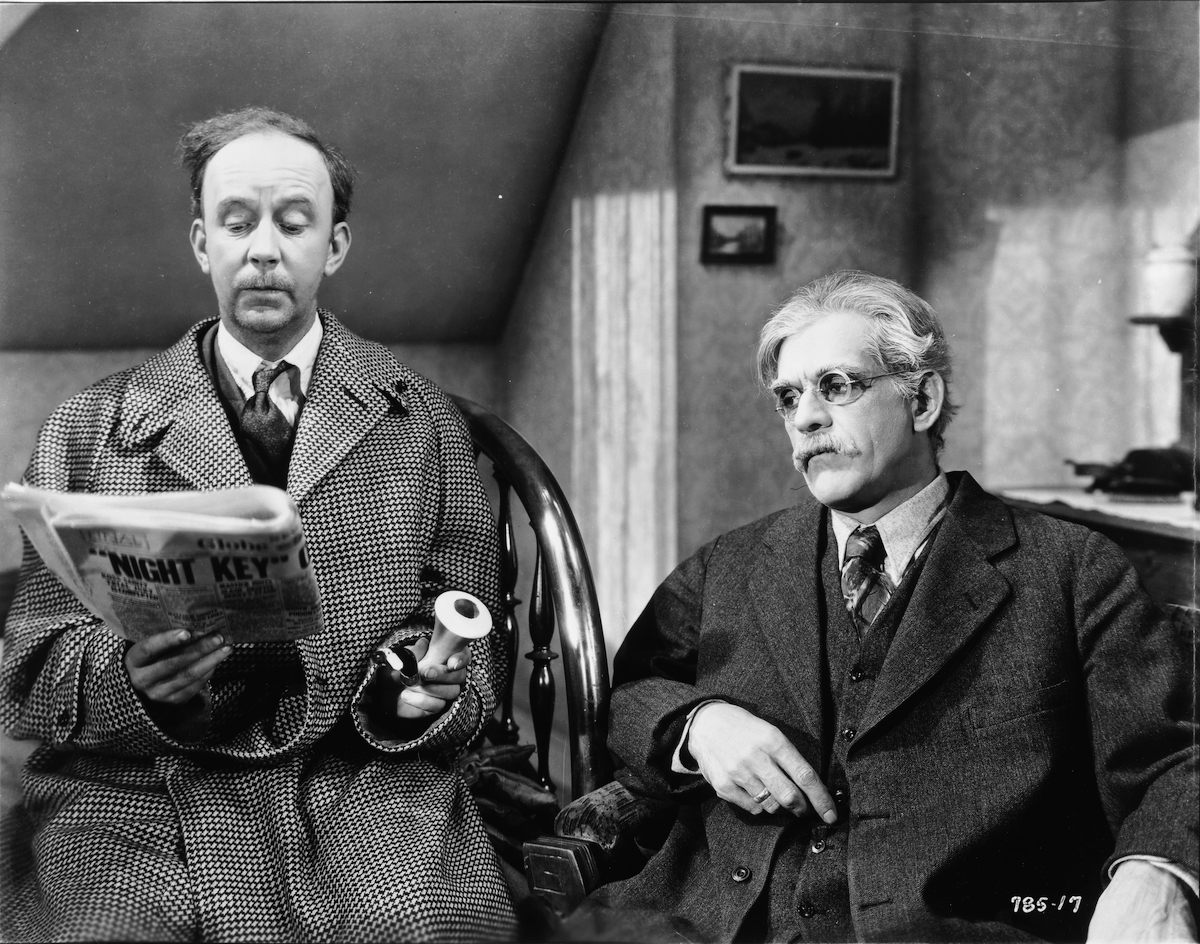

Night Key starts by extolling the wonders of marvels of modern alarm systems—to a pair of comedy Italians—and like many films of the period seems a little in awe of its subject, before moving into a plot that pitches the elderly inventor Mallory (Karloff) against the heartlessly profit-driven Ranger Protective Service.

Ranger has acquired the rights to Mallory’s latest creation, which seems to be a kind of laser-based alarm, but only with the intention of burying it lest it becomes a competitor to established electrical technology. It doesn’t help that the company’s boss (Samuel S. Hinds) and Mallory were previously rivals for the love of a woman who, naturally, married the much nicer latter.

Disappointed that his invention won’t be put into production, Mallory teams up with the small-time crook Petty Louie (Hobart Kavanaugh)—who initially seems only comic relief but proves to be crucial to the plot—with an ingenious plan. Using a gizmo that Mallory has created to disable Ranger’s existing alarms (which he also invented), they will break into premises protected by the systems, but not in order to steal anything: only to discredit Ranger. “What I create, I can destroy,” Mallory writes on the wall of one such target, signing it “Night Key”.

Hopes the individual non-burglaries might be staged with Se7en-like symbolism are raised when the pair rearrange clocks in a jewellery store to illustrate that Ranger has little time to mend its ways, but this fanciful line of plotting is soon abandoned in favour of something more every day. As word spreads of Mallory’s ability to get past Ranger’s alarm systems, a criminal gang leader known only as The Kid (Alan Baxter in a chilling performance) decides that Mallory must work for him on real robberies, against the law-abiding old man’s wishes.

Meanwhile, Ranger guard Jim Travers (Warren Hull) is falling in love with Mallory’s daughter (Jean Rogers), and given that the lines between the good guys and the bad guys are so clearly drawn it’s not difficult to guess who will emerge triumphant. Ward Bond also appears in a minor role; Lloyd Corrigan, the director, himself became better-known as an actor later in his career.

Night Key is a modest but very sturdy and well-made little thriller in which the characters of Mallory and his daughter are genuinely likeable people. The film has no very high aspirations, but those it does harbour, it more than meets.

USA | 1937 | 68 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

A beautiful young opera singer is menaced by an elderly doctor obsessed with her predecessor.

The Climax is loosely based on a much earlier play by Edward Locke, but the screenplay by Curt Siodmak (who in his time penned plenty of horror and sci-fi movies) owes its biggest debt to Phantom of the Opera (1943) and indeed was originally intended as a sequel. Filmed in saturated Technicolor, and receiving an Academy Award nomination for ‘Best Art Direction’, it’s certainly the grandest-looking of the three movies in Universal Terror, though its pomp can quite often shade into silliness.

The place isn’t Paris (as in Phantom), but somewhere in central Europe. The time isn’t clear; a reference to the middle-aged theatre prompter Carl (an entertaining Ludwig Stössel) having fought—presumably as a young man— in the 1866 Battle of Sadowa suggests it’s the late-19th-century, though it feels earlier. Still, given that all the signage in this obviously Germanic country is in English, and that the very American boy king (Scotty Beckett) would seem more at home on the baseball diamond than in the Royal Box at the opera house, perhaps it’s not wise to expect too much historical consistency.

Into this theatre at the beginning of the film sweeps Dr Hohner (Karloff); a nearby worker mentions his obsession with the singer Marcellina, missing for ten years now. Cue a fuzzy-iris framing effect and the flashback revelation that (surprise, surprise) the not-so-good doctor had killed Marcellina, so enthralled by the beauty of her singing that he could not bear the idea other men might experience it too.

Even a decade later he still forbids singing of a musical work called The Magic Voice, “sacred to the memory of Marcellina”. But (of course) along comes a young singer—Angela (Susanna Foster, who had played Christine in Phantom)—whose performances remind him too intensely of the dead woman, and he is infuriated by the rapturous reception she receives at the theatre.

Under the pretence of giving her a throat exam, Hohner hypnotises Angela to prevent her from ever singing again, a dirty trick that in not-quite-explained ways also necessitates him forcing her to carry an atomiser of mysterious liquid on her person at all times. The rest unfolds just as it should, especially when Angela’s fiancé Franz (Turhan Bey, “the Turkish delight”, in a charismatic performance) starts to have his suspicions.

Gale Sondergaard as a seemingly malicious housekeeper who turns out to defy expectations, Thomas Gomez as the theatre’s intelligent and kind but harassed proprietor, and Jane Farrar (also in Phantom) as a bitchy rival singer upstaged by Angela all contribute strong performances which add life to an essentially ridiculous tale. A slight hint of the supernatural when the doctor hears singing in his house is effective, too.

The main problem in The Climax isn’t its implausibility—that’s part of its charm, in fact—but the sheer bizarreness of the musical numbers, which hover somewhere between a more or less appropriate Franz Lehár operetta style and a completely inappropriate full-on Broadway musical idiom. They change tone much too quickly, as well: it’s easy to see why the film’s makers thought the shows-within-the-show ought to progress from introduction to climax in minutes or less, but the effect is absurd and (like the aw-shucks boy king) distracts from the dark story that The Climax is trying to tell.

USA | 1944 | 86 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

An Englishman in disguise tries to uncover the secrets of a German count and his castle.

The sets of The Black Castle, seeming vaguely familiar from other movies and clearly not physically substantial at all, are complemented by a full array of horror clichés from the opening moments: excitable music, a castle and “lightning”, soon followed by a cemetery, a howling wolf, and a creaking door. Lon Chaney Jr. appears, too, as a character who is not strictly a hunchback but might as well be.

Set in the Black Forest around 1800, The Black Castle follows the Englishman Sir Ronald (Richard Greene) as he visits, incognito, the wicked Count von Bruno (Stephen McNally) in an effort to discover the fate of two friends who have disappeared on the count’s estate. En route to the count’s, Sir Ronald stops only for a near-slapstick swordfight in an inn, as you do; the bulk of the story then takes place at the eponymous castle, complete with dungeons, a leopard, crocodiles, a beautiful countess (Rita Corday) and an internal layout that never quite adds up.

The scariest thing in the entire movie is, however, a metal figure in the count’s dungeon—seemingly an Iron Maiden torture device, probably based on the famous Nuremberg one. Truly creepy in its ghastliness, it may have been the creation of Nathan Juran, who was originally hired for the film’s art department and then promoted to director at short notice. He went on to have a notable career in science fiction, as did producer William Alland (who also played the reporter in Citizen Kane, which this most definitely ain’t).

To its credit, though The Black Castle is heavily laden with highly familiar tropes, it does keep you guessing. The problem with it is that Sir Ronald and the countess (with whom he predictably falls in love) are so bland we’re unlikely to really care whether they’re buried alive or not.

Much more engaging is the count himself, played by McNally with dastardly relish, and Burton’s manservant (Tudor Owen). Karloff is a decidedly secondary character, a doctor with a somewhat Munsters/Addams Family air, and never has much opportunity to enliven this, the least satisfactory of the Universal Terror trio.

USA | 1952 | 82 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

directors: Lloyd Corrigan (Key) • George Waggner (Climax) • Nathan H. Juran (Castle).

writers: Tristram Tupper, Jack Moffitt & William A. Pierce (Key) • Curt Siodmak, Lynn Starling & Edward Locke (Climax) • Jerry Sackheim (Castle).

starring: Boris Karloff • Warren Hull & Jean Rogers (Key) • Susanna Foster & Turhan Bey (Climax) • Richard Greene & Stephen McNally (Castle).