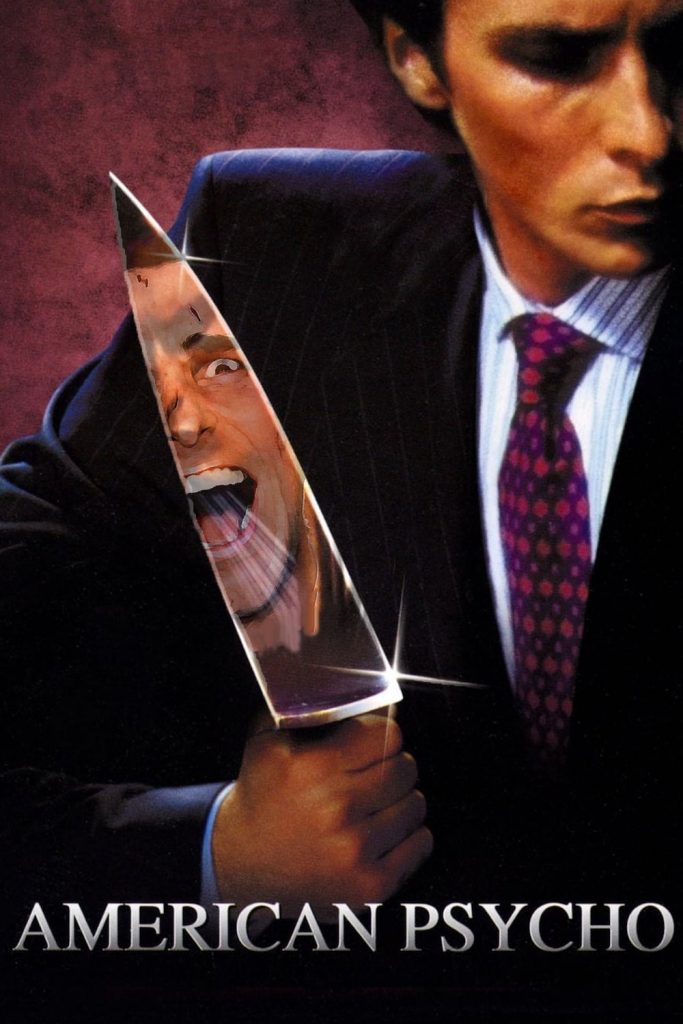

AMERICAN PSYCHO (2000)

A wealthy New York City investment banking executive, hides his alternate psychopathic ego from his co-workers and friends as he delves deeper into his violent, hedonistic fantasies.

A wealthy New York City investment banking executive, hides his alternate psychopathic ego from his co-workers and friends as he delves deeper into his violent, hedonistic fantasies.

Patrick Bateman, the antihero of Mary Harron’s American Psycho (adapting Bret Easton Ellis’s controversial 1991 novel), works on Wall Street, New York City. Or rather, he doesn’t work; for one of the film’s ironies is that while it’s set in a 1980s milieu of sharp-suited ‘greed-is-good’-style yuppies, none of them ever seems to actually turn the wheels of global finance. Instead, they spend their time competing over restaurant reservations and expensively-printed business cards, pretending to be socially conscious while not having a clue what they’re talking about (one laments the Sikhs killing Israelis in Sri Lanka), and hating each other while feigning deep friendship. Hating themselves, too, in the case of Bateman (Christian Bale).

“There is no real me, only an entity, something illusory,” Bateman says in voiceover. “I have all the characteristics of a human being… but not a single clear identifiable emotion except for greed and disgust.” Like his pals, he’s an empty machine built for consumerism, with a vast salary taking the challenge out of owning and consuming things, making him instead turn to murder in an effort to make himself feel something.

At least, that’s what he thinks he does, for American Psycho is decidedly ambiguous on whether Bateman’s slaughters take place anywhere beyond his own fragile mind. As the movie progresses, from restaurant to restaurant, bar to bar, line of coke to line of coke, there’s an increasingly surreal air to them and plausibility becomes increasingly stretched.

At one point, Bateman’s seen running naked through the corridors of an apartment building, smeared in blood while wielding a chainsaw. In another late scene, perhaps the one where Harron (as co-writer) encapsulates most cleverly her film’s slippery reality, Bateman enters what seems to be his office building, murders the security guard and a cleaner, then flees… but later enters another building that’s almost identical, greets a different security guard in what seems to be the exact same lobby and signs in as normal.

What happened there? Did Bateman get lost and enter a similar building and kill two people? Or did the first building not exist at all, outside of Bateman’s warped imagination? The minor differences between the two seem like something one might encounter in a dream.

The actual plot of American Psycho is of little importance. Superficially the story hangs on something of a McGuffin: a colleague of Bateman’s, Paul Allen (Jared Leto), has gone missing and Bateman believes he’s murdered him, after becoming annoyed at Allen for having a fancier business card. A private detective (Willem Dafoe) duly arrives to investigate Allen’s disappearance, politely but probingly questioning Bateman and pointing out the inconsistencies in his alibi. There’s even something about this detective that rings false, too, as he seems preoccupied with minor details that can hardly help him locate a missing man. So does he exist?

By the end of the movie, the oddness and apparent blurring of fantasy and reality permeate everything. Bateman is being mistaken for other people, who refuse to accept he is who he says he is. There are also large but still not conclusive revelations about Allen that throw into question many preceding events.

By this point, it’s as difficult for the viewer as for Bateman to get much of a grip on certainty. Only a few elements of American Psycho seem definitely anchored in the solid world, and it’s striking (especially given that the satire of Ellis’s novel had been widely misinterpreted as misogynistic) that two of the most salient are female characters: Bateman’s secretary Jean (Chloë Sevigny) and the street hooker Christie (Cara Seymour).

It may be no accident that they’re both relatively low on the socioeconomic scale, certainly compared to the wannabe Gordon Gekkos/Sherman McCoys of Bateman’s crowd. American Psycho, which isn’t a subtle film, may almost be saying they are more real because of this. Certainly, the only episode in which Bateman seems to feel genuine empathy for another person is a surprising and even touching scene in his apartment with Jean.

The rest of the time, though, Harron (whose filmography mostly revolves around female lead characters) simply has fun with the concept of Bateman being both a master of the universe and a serial killer. The film is more obviously tongue-in-cheek than the source material, and its title sequence sets that tone perfectly: whimsical music with red drops of “blood” that turn out to be splatters of nouvelle cuisine sauce. A precursor to the opening titles of Showtime’s TV series Dexter, perhaps.

Sometimes the humour is one of straightforward social parody: Bateman describes his grooming routine in obsessive detail (echoing the novel’s long recitations of brand names, although they’re less to the forefront here). At other times it’s more sinister: Bateman fills in a crossword with the words MEAT and BONE repeated over and over again.

And then there are moments where one gets the impression Harron and her co-writer Guinevere Turner just couldn’t resist a juicy line or macabre joke! For example, the way Bateman says “murders and executions” while the girl he’s chatting too mishears it as “mergers and acquisitions” (or does he really say that?), or the way that Bateman mentions notorious cannibal killer Ed Gein and a friend presumes he must be the maître d’ of a trendy bar.

American Psycho runs the risk, then, of being a slight and almost trivial film. And, indeed, it’s little more than one bold idea writ large, but done so smartly that Harron carries it off, aided by fine performances as well as excellent cinematography and music by Velvet Underground’s John Cale.

Bale is magnificent here, even if he can’t be accused of excessive subtlety. Bateman’s conversation, his mannerisms, and his physical movements are impeccably controlled. It’s all about preserving his perfect upwardly-mobile-young-financier image, so Bale’s performance exists almost entirely in his facial expressions. The way he sometimes snaps from politesse to aggression, then back again just as quickly, is a vivid symbol of the Jekyll & Hyde theme that underlies American Psycho.

The British-born Bale once again utterly convinces as an American, too. (Leonardo DiCaprio was considered for the role during the movie’s long development process but would have been unable to bring that same ice-coldness to it.)

Seymour and Sevigny, both vulnerable and cautious in their different ways, provide contrast. Dafoe is also intriguing; the conflict between his chummy manner and the underlying suspicion implied by his questions adding to the feeling that not everything’s as it seems. Matt Ross, meanwhile, is droll as the foppish Carruthers, a closeted gay colleague who develops a crush on Bateman.

The photography by Andrzej Sekuła (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction) is stark and chilly, perfectly reflecting the aesthetic of the ’80s when American Psycho takes place. Sets and costumes, likewise, are ruthlessly over-designed to the point of complete lifelessness. It’s no surprise that Bateman feels he has no identity; there’s hardly a whiff of personality in his stale corporate world.

Composer John Cale proves himself a versatile and effective film composer, easily transitioning from an almost comedic style after Bateman’s rejection of Carruthers, to a tenser Hitchcockian score as he returns to his murderous activities. Much fun is had, too, with Bateman’s pompous explanations of the lame pop music he plays to his victims before dispatching them (a lecture on Huey Lewis and the News, followed by an axe killing…).

In the end, American Psycho (which has no real connection with the terrible 2002 cash-in “sequel” American Psycho 2) is massively bleak despite all the humour that’s gone before. That’s another oddity, but it’s a powerful one, for this film’s jarring changes of tone (just like its unresolved plot questions) leave it lodged in our minds for days after,

And so does the way that Bateman—for all that he’s an appalling snob, an emotionally selfish user, and (perhaps?) a monstrous serial killer—is never totally detestable. Perhaps we don’t like him, but we feel for his plight, if only slightly: he’s a modern man trapped in the rat race of a capitalist and consumerist society, comfortable but distressingly empty inside. All good satire contains truths beneath the laughs, and that is American Psycho’s.

director: Mary Harron.

writer: Mary Harron & Guinevere Turner (based on the novel by Brett Easton Ellis).

starring: Christian Bale, Willem Dafoe, Jared Leto, Josh Lucas, Samantha Mathis, Matt Ross, Bill Sage, Chloë Sevigny, Cara Seymour, Justin Theroux, Guinevere Turner & Reese Witherspoon.