GOD TOLD ME TO (1976)

A New York detective investigates a series of inexplicable and savage crimes, linked only by the perpetrators claiming that “God told me to...”

A New York detective investigates a series of inexplicable and savage crimes, linked only by the perpetrators claiming that “God told me to...”

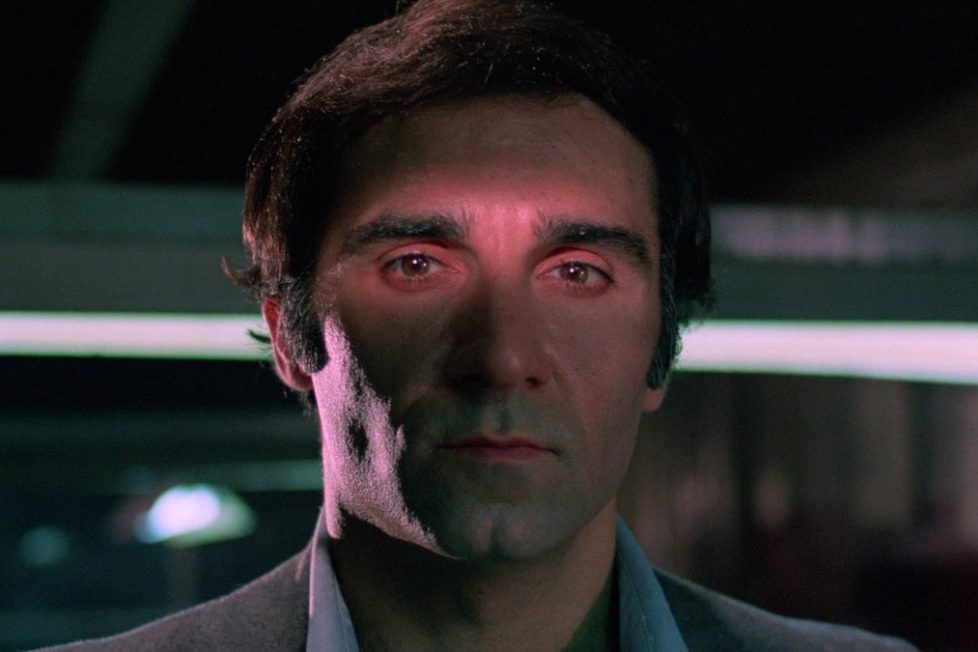

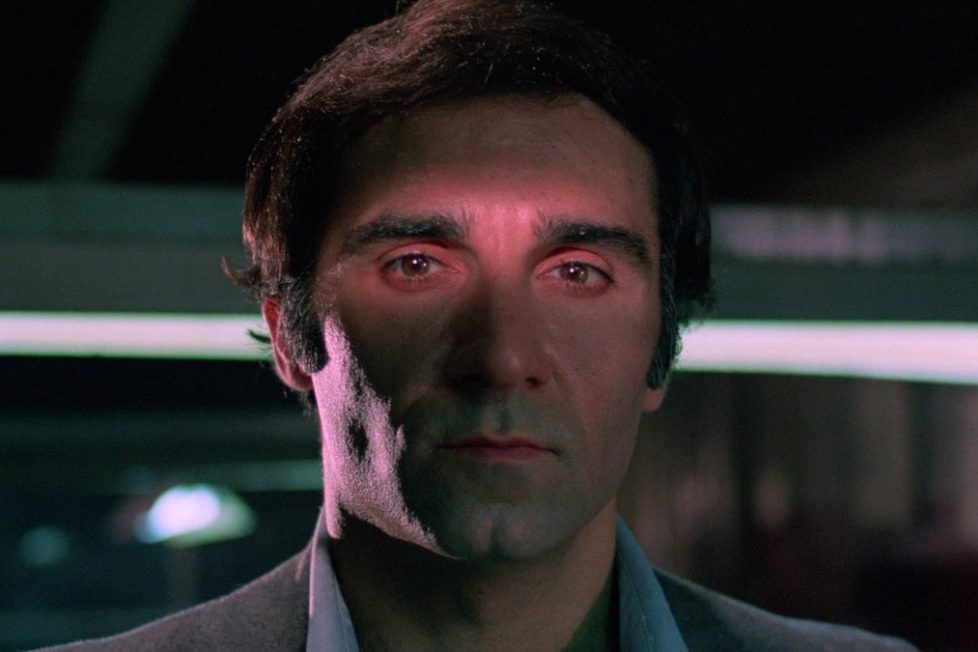

God descended to the big screen in 1975 to appear in Monty Python and the Holy Grail (animated by Terry Gilliam and voiced by Graham Chapman), and again in 1977, this time incarnated as a twinkly old man by George Burns for Oh, God! Neither portrayal was conventionally reverent, but they’re downright traditional alongside the God—or putative God—played by Richard Lynch in Larry Cohen’s God Told Me To, an extraordinary, trippy fusion of Big Apple police procedural, post-Exorcist theological horror, and 1970s paranoia.

Cohen’s film is undeniably flawed: the storyline is a non-stop series of revelations rather than a plot in the normal sense, narrative jumps can leave the audience confused, and occasional forays into outright sci-fi SFX (some of them using footage from UK TV series Space: 1999) sit uncomfortably with the handheld realism of the New York scenes. But its strangeness and its ever-present sense of all-enclosing evil make it one of the most forcefully weird movies of the era, and one that deserves to be far better known.

The opening is stunning and sets a standard many stretches of the movie can’t quite reach, though there are at least a couple of scenes that come close. After an abstract title sequence that seems to depict shooting stars to a soundtrack of Gregorian chant (though Cohen more memorably described them as a “semen-like substance floating across the universe”, the relevance of which later becomes clear), the film proper opens with a mundane NYC street scene on a bright day.

The frame is thronged with pedestrians and cars; among them is a cyclist who seems to be just part of the background, passing by while we await the arrival of really important characters—until, without warning, he’s shot by an unseen gunman. No sooner has he fallen off his bike than another person is struck down, then another, then another; in all, 15 people are killed in a short sequence where at times it feels like almost every shot is a shooting. It’s as attention-grabbing as a Jaws (1975) attack but more disturbing for coming completely out of the blue in a cinematically familiar setting, and it feels like it isn’t going to stop.

There will be more disturbingly raw violence later in the movie, notably in a Psycho (1960)-like attack on a staircase. First, though, it settles into a procedural routine, introducing detective Peter Nicholas (Tony Lo Bianco) as he climbs the water tower where the shooter’s perched; they engage in conversation; the killer is oddly chirpy, almost light-hearted; Nicholas asks him why he did it; “God told me to”, he says.

And the same rationale will soon be offered up by the perpetrators of other apparently random slayings, including a personable guy who matter-of-factly discusses shooting his wife and two kids (“I thought I’d do something for Him after all He’s done for us”, says this killer, played by David Morten with the same chilling casualness as the water-tower sniper). Another man stabbed strangers at the supermarket; another turned on fellow police officers at a St Patrick’s Day parade (along with the opening, this is the biggest set-piece in a film that’s mostly of modest scale, much of it filmed illegally by Cohen and his crew at the real parade).

Before too long Nicholas, pursuing an elusive—and for a long time unseen—young man who appears to be linked to the perpetrators of these rampages, will come to suspect that “God told me to” is not just delusional or metaphorical. Eventually, too, he will also discover things that challenge not only his own religious devotion but his entire understanding of who he is.

Plenty of hints are dropped along the way, both in the script (“people have told me it is physically impossible”, the sniper’s mother says of her son’s crime; “I wonder what guided his hand”, muses Nicholas) and stylistically (via God’s-eye-view overhead shots, for example). Later on there are indications that the God of this movie may not be exactly what we were taught (“he never comes upstairs… I always go down to the furnace room”).

The use of colour by Cohen and cinematographer Paul Glickman is especially striking in drawing a distinction between the mundane world we know and the hidden realities beneath it; earlier passages are full of strongly contrasted colours (for example a red-coated woman standing alongside a red car as two yellow cabs pass, or the many uniforms and brass instruments of the St Patrick’s Day parade), but in scenes where the surprising truth about God is closer, single hues are much more dominant, in a more conventional horror style. The deity himself, if that’s what he really is, appears to be drenched in butter-yellow light.

Thanks in part to touches like these, the film has a sense of gravity and fatefulness even at its more procedural moments, though it would be a mistake to take God Tod Me Too too seriously as a philosophical treatise; its view of Christianity is decidedly simplistic (it’s clear that the Biblical God didn’t order Abraham to kill Isaac because he actually wanted to see the boy slaughtered) and much hinges on the thoroughly debunked “ancient astronauts” ideas championed by Erich von Däniken in his book Chariots of the Gods? (1968). More interesting ideas that Cohen has discussed in interview, for example that a person with superhuman powers might believe themselves to be a god, are not fully developed in the film.

Some structural narrative problems don’t help either: Nicholas seems to know too much too quickly, and a few brief changes in point of view—notably, one depicting a meeting of conspirators that Nicholas can’t have been aware of—undermine our identification with the detective. Roger Ebert called it “the most confused feature-length film I’ve ever seen”, which is perhaps unfair, though there’s little question that God Told Me To is much clearer on a second viewing.

Even at its more puzzling moments, though, God Told Me To has a great deal to offer not only in atmosphere but also in performances. Lo Bianco, then a relatively familiar face from TV and a prominent role in The French Connection (1971), is completely persuasive as the detective who, in uncovering the truth, also finds himself trying to deny things he wishes he hadn’t learned. There is a real sense of a relationship with his girlfriend Casey (Deborah Raffin), too. In smaller roles, highlights include Sam Levene as a science journalist interested in radical theories; Lester Rawlins as an anxious initiate into a huge secret; Sylvia Sidney as an elderly mother; and both John Heffernan and Alan Cauldwell, playing the old and (in flashback) younger versions of a key witness.

The score by Frank Cordell—sadly his last—frequently provides effective support, though less so when the composer gives in to the temptation of over-emphasising dramatic moments. (Cohen had wanted the great Bernard Herrmann, who provided the music for his 1974 It’s Alive, to write God Told Me To’s score as well, and indeed claims that a pre-release cut was the last film Herrmann watched; but the composer died before the plan could come to fruition, leaving Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and Brian De Palma’s Obsession as more famous swansongs.)

God Told Me To did not have an easy entry into the world, meeting an inevitably frosty reception when it opened in religious Texas. Producers Edgar J. Scherick and Daniel H. Blatt asked for their names to be removed, and the film was for a while renamed Demon, completely obscuring the point Cohen was trying to make about the association of the Christian God with violence and destruction but presumably satisfying those who weren’t keen for it to be emphasised. (Alien was also considered as an alternative title, but rejected amid concern that audiences would think the movie was about illegal migrants from Mexico; that didn’t bother Ridley Scott much three years later.)

In the 45 years since its release, though, it has gained a following and more critical respect; Gaspar Noé even considered a remake at one point, though the idea seems to have been abandoned. If it were to be remade, the result would surely be a very different film, partly because its commentary on a God who kills innocents (especially New York ones) would inevitably be seen in post-9/11 terms, but also because its success is so dependent on that peculiarly 1970s mix of cynicism and naivety. Like the alternative deity it proposes, God Told Me To is far from perfect, but it is powerful, surprising and difficult to forget.

USA | 1976 | 91 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Larry Cohen.

starring: Tony Lo Bianco, Deborah Raffin & Richard Lynch.