Frame Rated’s 4 Favourite Romantic Films

Four personal choices for the greatest romantic film ever made, to watch on Valentine's Day.

Four personal choices for the greatest romantic film ever made, to watch on Valentine's Day.

When Harry Met Sally… is one of the rare romantic comedies that actually understands time. Not time as a backdrop, but time as pressure—the slow, sometimes irritating force that erodes certainties and exposes what people really want. The film doesn’t hinge on grand gestures or destiny; it hinges on duration. It’s about conversations that repeat,arguments that evolve, and feelings that refuse to stay in their assigned boxes.

Harry and Sally don’t fall in love because they’re “meant to”. They fall in love because they keep running into each other at different moments in their lives, each time slightly misaligned with who they think they are. The film’s great trick is letting those misalignments accumulate. What begins as ideological conflict—Harry’s cynicism versus Sally’s optimism, control versus improvisation—gradually becomes intimacy, not through resolution but through erosion.

Rob Reiner stages this as a comedy of friction rather than charm. The dialogue is sharp, often defensive, and occasionally cruel. Harry isn’t softened into a lovable rogue, and Sally isn’t idealised into a manic fantasy. They’re annoying in recognisable ways. That annoyance is the point: the film understands that attraction often grows not despite irritation, but through it.

What makes When Harry Met Sally… endure is its refusal to rush emotional clarity. The famous question—can men and women be friends?—is never answered abstractly. It’s tested, broken, reformulated, and tested again. Friendship here isn’t a holding pattern before romance; it’s the terrain where romance becomes possible at all. By the time love arrives,it feels earned—not because it’s dramatic, but because the characters are tired of pretending otherwise.

Nora Ephron’s script gives romance something rarely allowed in the genre: self-awareness without irony. The film knows its own conventions, but it doesn’t sneer at them. It lets fantasy and realism coexist—the New York seasons, the split screens, the interviews with elderly couples—while grounding everything in emotional recognisability. Even the iconic lines work because they sound like things people might actually say when they’ve run out of better strategies.

The final scene remains one of the most beautiful love declarations in cinema history—not because it’s poetic, but because it’s specific, neurotic, and slightly embarrassing. Harry doesn’t promise eternity; he admits preference. He lists Sally’s quirks as evidence: the way she orders food, the way she gets cold, and the fact that it takes her an hour and a half to say goodbye on the phone. He doesn’t transcend himself; he exposes himself. That’s the film’s quiet thesis: love isn’t about transformation, but about choosing someone with full awareness of their particularities—and your own.

In this, When Harry Met Sally… shares something essential with Paddy Chayefsky’s Marty (1955): both films reject Hollywood’s romanticised ideal and centre ordinary people navigating loneliness and longing. But where Marty is raw and almost neorealist—no glamour, no New York postcard—Ephron and Reiner refine that honesty into something funnier, lighter, and more structurally elegant. Marty’s love is whispered, tentative, and burdened by shame. Harry’s is louder and more self-aware, but no less vulnerable.

As a Valentine’s pick, When Harry Met Sally… works not because it sells romance as bliss, but because it frames it as recognition over time. Love here isn’t fate striking once; it’s persistence paying off. And that, decades later, still feels disarmingly honest.

Hollywood has long portrayed love as a grand spectacle built around extravagant gestures and melodramatic contrivances. Romantic relationships are often presented as stories that promise emotional safety and permanence once narrative obstacles have been overcome. Richard Linklater’s celebrated Before trilogy stands in deliberate opposition to this fantasy. Collectively, the triptych functions as an overarching cinematic meditation on the evanescence of love against the sweeping grandeur of time. Yet, each instalment also stands independently as a beautifully concentrated distillation of a particular moment in a relationship.

Before Sunrise optimistically captures the intoxication of new connections as it chronicles the first meeting between Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Céline (Julie Delpy). At the other end of the scale, Before Midnight (2013) confronts the sobering challenges of maintaining that idealism, exposing how repetition and compromise can erode a romantic connection. Situated between these two extremes is Before Sunset (2004)—the trilogy’s most delicate and devastating entry, and arguably one of cinema’s most beautiful expressions of romance.

Taking place nine years after their fleeting encounter in Vienna, the film finds Jesse a moderately successful novelist and Céline an environmental and humanitarian activist. During the final stop of Jesse’s promotional book tour, he serendipitously reunites with his former lover. With only an afternoon to spare before Jesse must leave for the airport, the pair rekindle their chemistry as they drift through Paris discussing professional setbacks, marital disappointments, and the compromises of adulthood.

The conceit is deceptively simple, but within this modest framework Linklater constructs a profound meditation on love and regret. As Jesse and Céline walk along the Promenade Plantée and the banks of the Seine, their conversation effortlessly slips back into the flirtatious digressions and philosophical musings of their youth. Yet, despite the golden glow of the afternoon’s “magic hour”, the reunion is suffused with a melancholic shadow. Both characters have matured since their previous encounter and now carry the burden of failed relationships and unfulfilled ambitions.

Co-written by Hawke, Delpy, and Linklater, the screenplay brims with an authentic vulnerability, and the actors deliver performances of extraordinary restraint. The subtle gestures of their body language communicate a separate conversation running parallel to the dialogue—one steeped in longing and unspoken emotions. A stolen glance, a lingering smile, or an unintentional touch reveals a decade of suppressed affection. Yet, the anticipation of romance is haunted by a shared understanding of mortality and the finitude of love itself. Linklater denies the audience easy catharsis, opting to end on a note of deliberate ambiguity. However, it’s within this unresolved tension that Before Sunset articulates its most inspiring and painful truth: love’s power lies in its impermanence, and it must be seized before it’s lost forever.

The films of Wong Kar-wai exude a profound sense of longing and a quest for comfort. Yet the absurd, in all its uncontrollable splendour, often spoils any hope of these desires being fulfilled, leaving survivors of emotional tragedy to ruminate on the better days of yesteryear. The subject matter is the absurdity of romance—grounded and relatable, yet deeply melancholic.

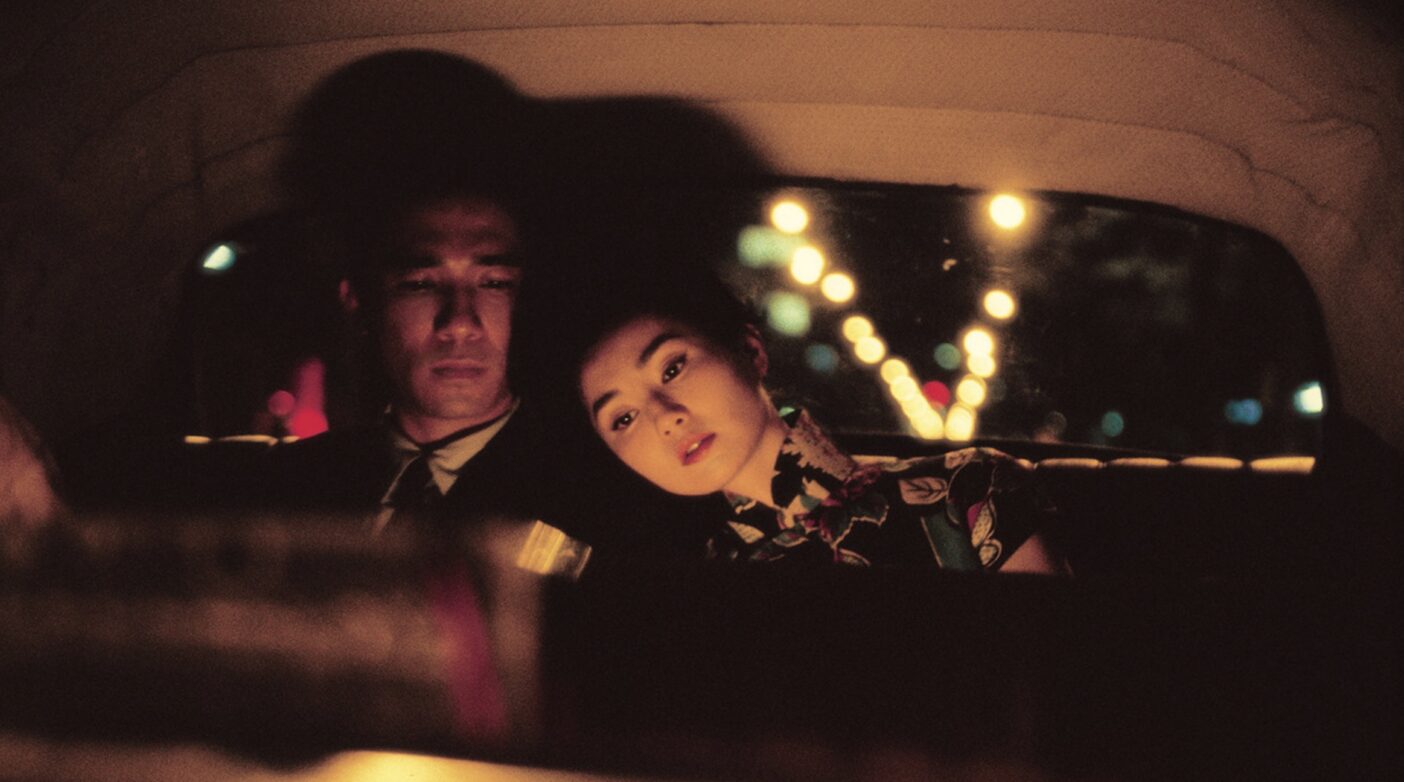

In the Mood for Love focuses on two married individuals grappling with the painful reality of their spouses’ adultery. From this shared grief, an unexpected bond develops, though cultural norms and moral values prevent it from fully blossoming. Wong tells the story through a fragmented chronological order that reflects the nature of memory. Moments, regardless of how small they may seem, serve as distinct instances in time, revealed through subtle changes in attire—even something as simple as a tie. These shifts illustrate the extensive duration of this romantic suffering.

At first glance, these details are easily missed; the film’s cinematography lulls the viewer into a state of allurement. However, with further exposure, one notices a visual subtlety that allows these temporal fragments to be dissected, revealing layered intricacies akin to the inner workings of a pocket watch. It’s remarkable how much sustenance Wong Kar-wai provides his audience to chew on within a concept as universal as love.

The film’s melancholia is heightened by an aching orchestral score that reverberates over fleeting moments of connection, often captured in slow motion to match the music’s tempo. This continuous waltz of the senses creates a hypnotic experience, drawing the viewer into an immersive journey through an unattainable past and evoking a synthesis of euphoric nostalgia and sorrow. Even now, I find myself revisiting the soundtrack to bask in its woeful essence while away from home.

Set in 1960s Hong Kong, the film captures an era where population density was reaching an all-time high and living arrangements were becoming increasingly cramped. Cinematographers Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bin reflect this claustrophobia by framing the leads within a frame—conversations unfold in the narrow confines of doorways, windows, hallways, or alleyways. This creates a suffocating atmosphere that not only reflects the reality of the city but also highlights a specific cultural pressure: voyeurism and the gossip that inevitably follows.

As Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung Chiu-wai) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung) spend time together to understand their spouses’ affair, they draw the suspicious eyes of their landlords. This adds a layer of paranoia to their intentions, ultimately hindering their attempts to rationalise the situation. We, too, are granted a voyeuristic perspective; we view this memory as outsiders, becoming part of the very scrutiny that haunts them.

In the Mood for Love is cinematic perfection. It’s sensual, yet it aches alongside its elegantly abstracted cinematography and ingenious visual temporality. It is, without doubt, my favourite romance and one of my all-time favourite films. Its effect never diminishes with repeated viewings. If you ask me, that’s what love is all about: unwavering passion, tantalisation, and worship.

Written by Diane Drake and directed by Norman Jewison, Only You doesn’t usually make the list of favourite modern romantic comedies. That’s partly because, despite its mid-1990s setting, it isn’t modern at all. Instead, it harks back to the golden age of Hollywood, when characters made insane, impulsive decisions in the name of love and dramatic declarations were the norm. That’s exactly why it remains my favourite cosy Valentine’s Day film.

The story itself feels like something out of a fairy tale. Our heroine, Faith (Marisa Tomei), is a poetry teacher and a romantic who still remembers an incident with an Ouija board from her childhood. The board told her she would “say I do” to a man named Damon Bradley—a prediction later confirmed by a carnival fortune teller. Just 10 days before Faith is due to marry a podiatrist, she receives a call from Damon Bradley himself, an old classmate of her fiancé who is currently travelling through Italy. She immediately sets off for the continent, dragging along her reluctant best friend (Bonnie Hunt) in search of her destiny. She ends up meeting not Damon Bradley, but Peter Wright (Robert Downey Jr.), a charismatic and equally impulsive shoe salesman who begins his own journey to prove he’s the man for her.

Of course, the ridiculous situations rife within this complicated scenario make for great comedy. Bonnie Hunt, in particular, is excellent, with impeccable line delivery. Likewise, the cinematography is stunning; the film was shot on location in various cities and across the countryside of the Italian peninsula. Indeed, much of the film serves as a “Visit Italy” advertisement.

But the real reason this film has become my go-to for Valentine’s Day is that it’s an old-style flick that asks nothing of me. When I put this on, there’s no need to think and no big moral questions to debate. I can simply sit back and enjoy the easy ride, like floating on a gondola in a Venetian canal.

There’s a fairy tale quality to the film where characters exist to feed the story, rather than the other way around. These characters don’t feel “real” in the contemporary sense. They make foolish decisions, embark on logistically impossible adventures, and make bold public declarations that would get a real person sectioned rather than sent to Rome for the weekend. But they’re likeable heroes who teach us that happy endings really do exist.

In that way, it’s everything more modern, cynical romance films are not. There’s no cynicism, moral grey area, or even a hint of reality in Only You. Instead, we get fun adventures in beautiful settings and a happy ending that leaves us sighing and daydreaming. In my opinion, that’s the perfect way to spend Valentine’s Day.