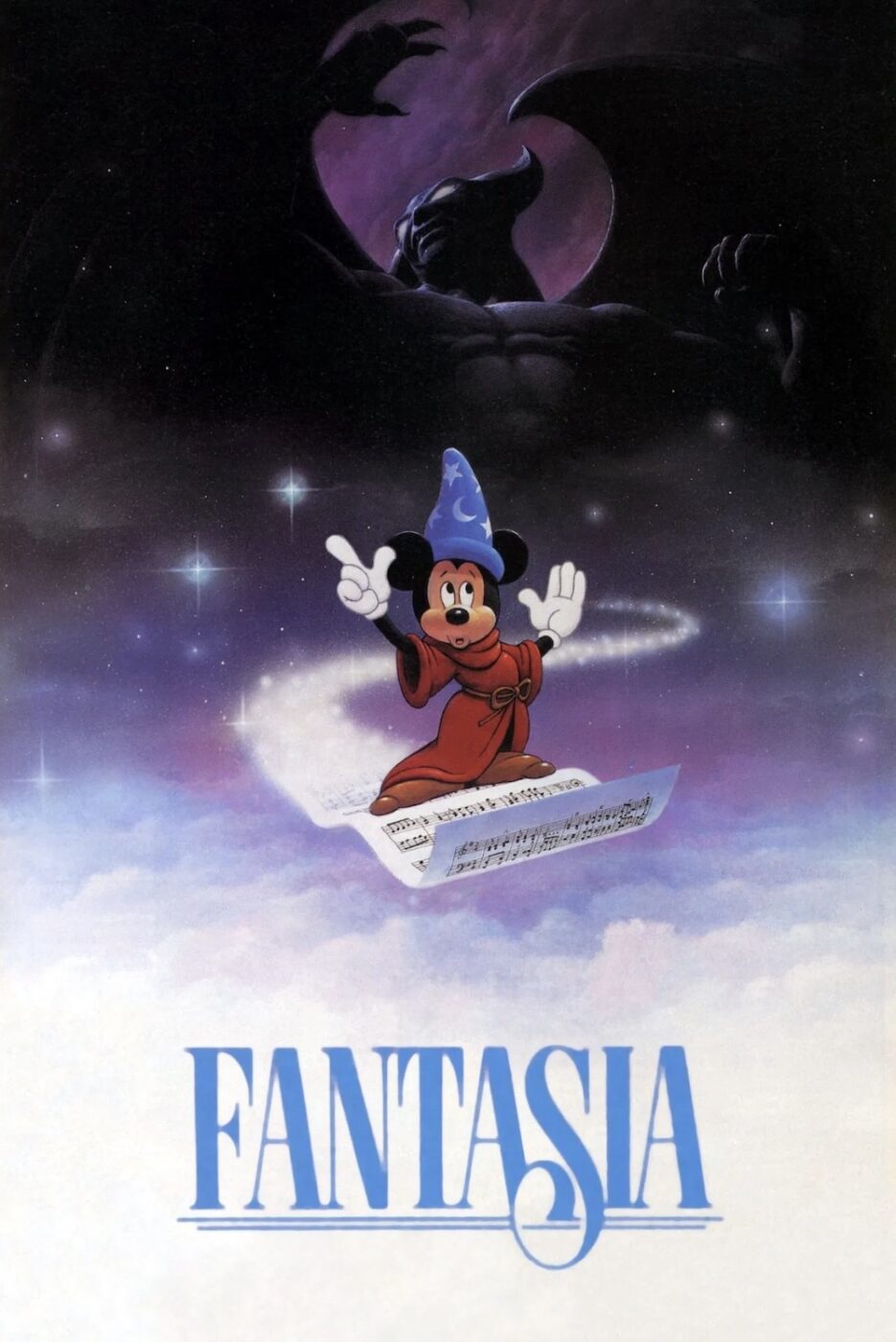

FANTASIA (1940)

A series of eight famous pieces of classical music, conducted by Leopold Stokowski and interpreted in animation by Walt Disney's team of artists.

A series of eight famous pieces of classical music, conducted by Leopold Stokowski and interpreted in animation by Walt Disney's team of artists.

When I was six years old, I was the weird kid at my school. Aside from being spacey and slow to answer the teacher’s questions, I also had strange tastes. Instead of cartoons, I loved old Hollywood musicals. I was also the only child in my class who liked the Disney classic Fantasia. And not just Mickey Mouse’s iconic “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” segment, but all of it.

This was partly due to Fantasia being one of my four-year-old sister’s “dance movies”, that she’d put on whenever she wanted to wear her pink tutu and twirl around the room. But I also couldn’t help but be enchanted by the idea that classical music didn’t have to be boring. You could listen to it and make up stories in your head inspired by the music. Fantasia encouraged daydreaming in a way most institutions and people in my life didn’t.

Today, when I look at Fantasia’s hand-drawn animation in light of the ’40s time period and consider all the love, sweat, and tears that went into making it, I can’t help but stand in awe of the Disney team’s imagination, innovation, and sheer creative genius.

Fantasia was the third animated feature released by the Walt Disney company, but the first to depart from the fairy tale or children’s story formula of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1938) and Pinocchio (1940). Rather than tell a single story, Fantasia’s an anthology of eight tales set to classical music conducted by Leopold Stokowski: “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor”, “The Nutcracker Suite”, “The Rite of Spring”, “The Pastoral Symphony”, “Dance of the Hours”, “Night on Bald Mountain”, and the aforementioned “Sorcerer’s Apprentice”.

Oddly, or fittingly, whichever way one chooses to see it, the original intention of the film was a marketing ploy to boost the popularity of Mickey Mouse.

Disney had already begun producing a series of short animated films called Silly Symphonies that set classical symphonic pieces against silly, slapstick stories featuring Disney cartoon characters. In 1936, Walt Disney noticed that his beloved Mickey Mouse was falling in popularity, as Donald Duck and Goofy became the audience’s new favourites.

In an attempt to boost the mouse’s image, he created a concept for a Silly Symphony short based on the German writer Goethe’s 1797 poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”. The short would be set to an instrumental, orchestral piece also inspired by the prose, written by classical composer Paul Dukas.

Disney mentioned his plans for the short while dining at a Hollywood restaurant with a group that happened to include Leopold Stokowski, the conductor of the famed Philadelphia Orchestra. As it turned out, the Dukas piece was a favourite of Stokowski’s; so much so that he offered to conduct the piece for free.

Of course, when it turned out that the intricacies of the short, including both the animation, new orchestrations, and a full orchestra, would be too expensive to make a profit as a Silly Symphony, Walt developed a new idea. He would feature the short amidst other animations set to pieces of instrumental classical music.

There were long periods of development with the Disney story team led by Joe Grant and Dick Huemer, along with Leopold Stokowski and music critic Deems Taylor, who would act as the film’s narrator. After years of debate, they chose six classical pieces that would feature in the film, along with six miniature scenes and stories to accompany them. To enhance the sound for the film, Disney recorded the musicians on multiple audio channels using ‘Fantasound’—an early version of now-common surround sound.

Upon the film’s release, despite a few classical music aficionados turning up their noses at the very idea of animation being married to their precious music, cinema critics raved about the endeavour. These film critics saw what I did as a young child. Daydreams set to music and shared with the world on the large screen.

All the scenes are visually stunning, but there’s a reason “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” has become the iconic image from the anthology. And it’s easy to see why it was the first and most expensive idea for this anthology. It’s the only short that contains a real sense of story and character that other Disney features are known for. It also achieved its goal of making Mickey Mouse popular again. And that’s because of something Mickey, up until this point, had been lacking: character flaws.

The reason kids gravitated towards Donald Duck and Goofy is that they saw themselves in them. They knew that they could be forgetful and clumsy like Goofy was; they also knew that they could get very angry when things didn’t go their way, like Donald Duck did. Amplifying these very human characteristics helped kids learn to laugh at themselves.

If you watch Mickey’s short film offerings before 1940, you’ll find the now-famous mouse showed none of these characteristics. He was the perfect vision of a hero. Always clever, always sweet, always getting the girl. But in “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” we saw a different mouse.

Mickey plays the titular apprentice of the sorcerer, Yin-Sid. When his master leaves Mickey with instructions to mop and sweep the workspace, Mickey looks through the sorcerer’s spell book to find magic that will help the cleaning along. Of course, it goes horribly awry, and Yin-Sid is forced to return early to set everything right.

Showing Mickey Mouse as someone well-intentioned but a bit lazy and clever but too ambitious for his own good was exactly the type of humour the average cinema attendee needed. Kids could now relate to the rascally rodent on the same level as Donald Duck and Goofy.

“The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” is the segment that truly deserves the loudest praise because it’s the only one in the anthology with a fully developed story and characters with an arc. The other vignettes, including a baby Pegasus learning to fly in Beethoven’s “Pastoral Symphony (Symphony number 6),” a variety of animals waltzing together in Ponchielli’s “The Dance of the Hours” from La Gioconda, and a demon summoning evil spirits and restless souls in “Night on Bald Mountain” by Mussorgsky, contain fun little characters but no true tale that children can get lost in.

That’s something that truly sets Fantasia apart from every other Disney feature. Since its creation, Disney’s prided itself on creating animation not as a spectacle, but in the service of a story. Here, animation is still not quite a spectacle, but it’s in full service to music.

What made this film less of a hit with children than other Disney films has also earned it a rightful place on AFI’s ‘100 Best Films’ list and seen it preserved in the Library of Congress as a film of historical and artistic note. Fantasia not only creates a visual and auditory feast for the eyes and ears, but it also encourages the viewer to think about classical pieces in entirely new ways.

The visions the animators had for pieces such as the “Nutcracker Suite” medley and “Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony” were nothing like the themes originally intended for the music. These changes were not always appreciated, even by the musicians who collaborated on the film.

Stokowski, for example, who is frequently seen in shadow conducting the orchestra in the film, was famously reluctant to go along with the Disney team’s plan to create a Greek mythology animation set to “Beethoven’s Sixth”. The conductor insisted that there were no mythological themes present in the music, and a connection with Greece was never so much as hinted at.

The other classical music adviser, Deems Taylor, a well-known symphony and music critic who also narrated Fantasia, saw what Disney was trying to do. The Disney animators were not creating animation that would cater to a composer’s original intent. Instead, they were listening to the music and showing the audience what that music conjured up for them. Showing the world their daydreams.

The thing about daydreams is that they are wild. They don’t conform to expectations or story, or a composer’s intent. They tend, rather, to fly all over the place. Flitting lightly from one image or thought to another and creating a chaotic, beautiful tapestry as they move.

That is what makes some people love Fantasia and some hate it. It’s a series of daydreams that several animators came up with while listening to classical music. That is art in its purest form. The most magical creations come forth when an artist, for the length of a film, or a novel, or a song, shares their daydreams with the world.

That’s why Fantasia joined my list of favourite childhood films. The sheer enchantment of fish swimming gracefully to the Arabian dance from the “Nutcracker”, and fairies dancing through the forest, echoed something in me. Fantasia showed me that other people daydream like me. It also showed me that there is a class of people in the world who are not ashamed of their daydreams. Rather, they take pride in them. They animate them and put them on display for everyone to see.

As this classic has been listed as a favourite by generations of Disney fans from around the world, it appears that I am not alone. Dreamy children, cut from the same cloth as me and my little sister, will continue to learn the value of daydreams set to music through Fantasia for years to come.

USA | 1940 | 126 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

directors: Samuel Armstrong, James Algar (Sorcerer), Bill Roberts, Paul Satterfield, Ben Sharpsteen, David D. Hand, Hamilton Luske, Jim Handley, Ford Beebe, T. Hee (Dance), Norman Ferguson (Dance) & Wilfred Jackson (Night, Maria).

writers: Joe Grant & Dick Huemer.

starring: Leopold Stokowski, Deem Taylor & The Philadelphia Orchestra.