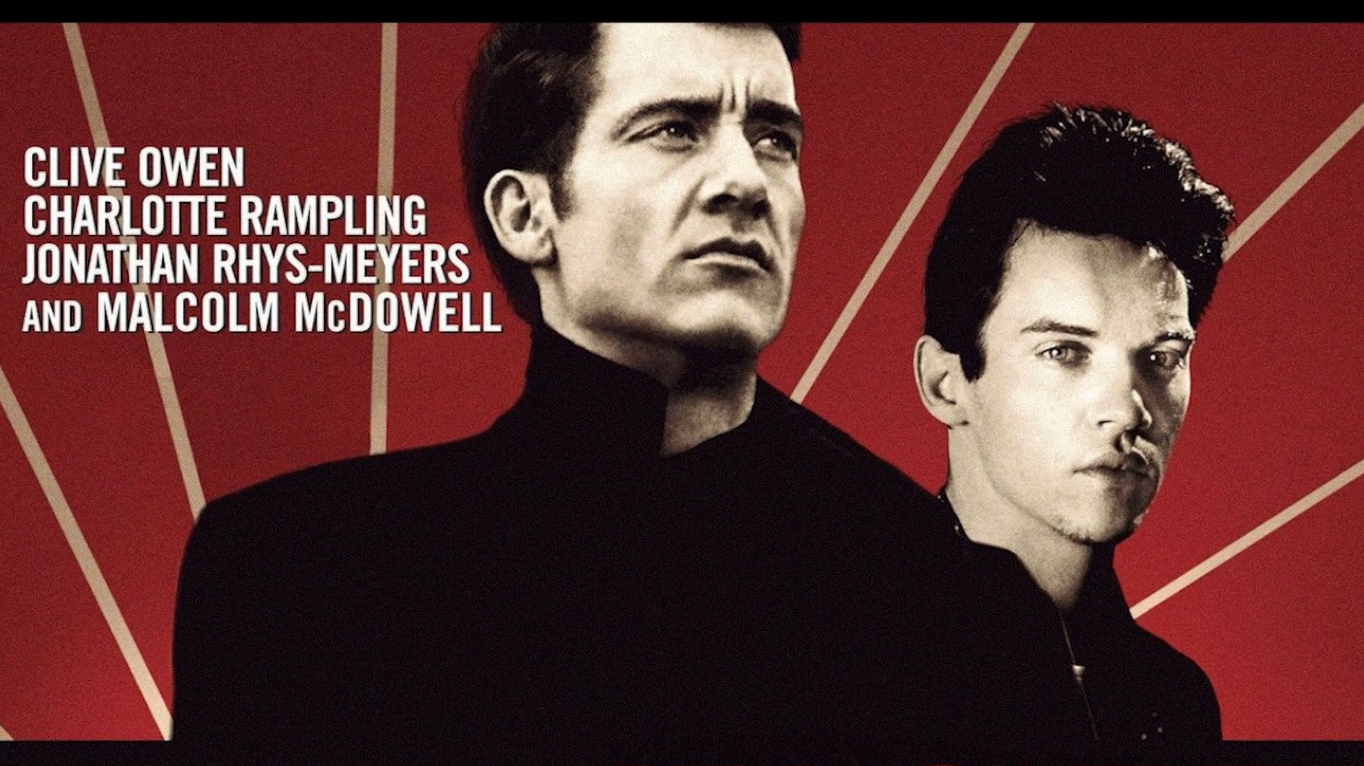

CROUPIER (1998)

An aspiring writer is hired as a croupier at a casino, where he realizes that his life as a croupier would make a great novel.

An aspiring writer is hired as a croupier at a casino, where he realizes that his life as a croupier would make a great novel.

In terms of craft, Croupier may well be director Mike Hodges’ finest film to date, certainly as much a contender as his revered debut Get Carter (1971), the classic hard-boiled crime thriller. Though it’s another of his films, Pulp (1972), that Croupier most resonates with, as both feature a writer as protagonist and rely on extensive voiceovers to counterpoint what we see happening with how the narrator tells it. So, Croupier joins this canon of clever films about authors and is most likely to appeal to those who fancy themselves as one. However, whereas Pulp was a darkly comic satire from the saucy 1970s, Croupier is an altogether sleeker, colder affair from the nihilistic 1990s. A character study that’ll only raise a horrid smile from those in accord with its cruel sense of irony, of which there’s plenty.

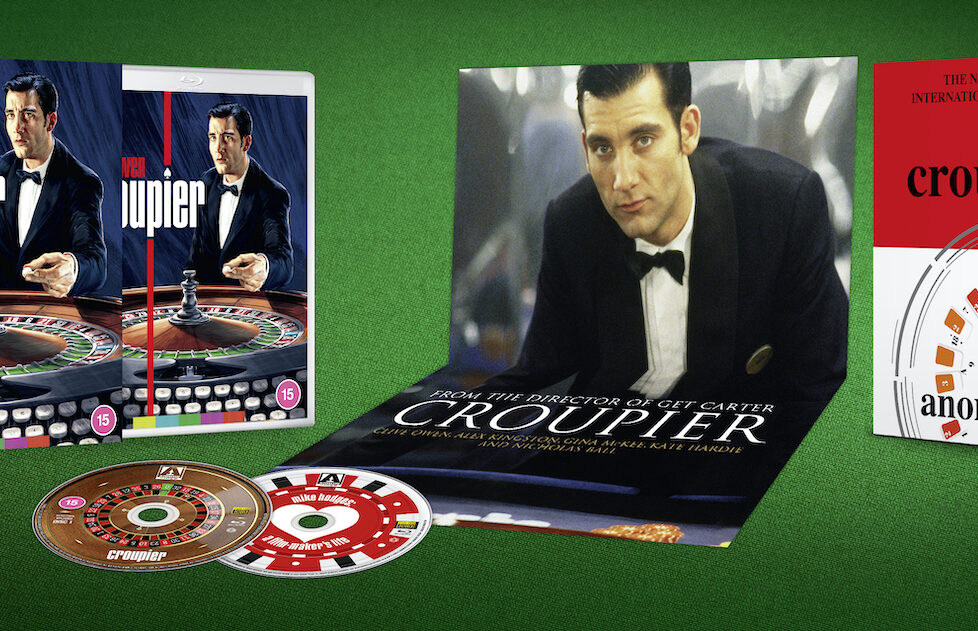

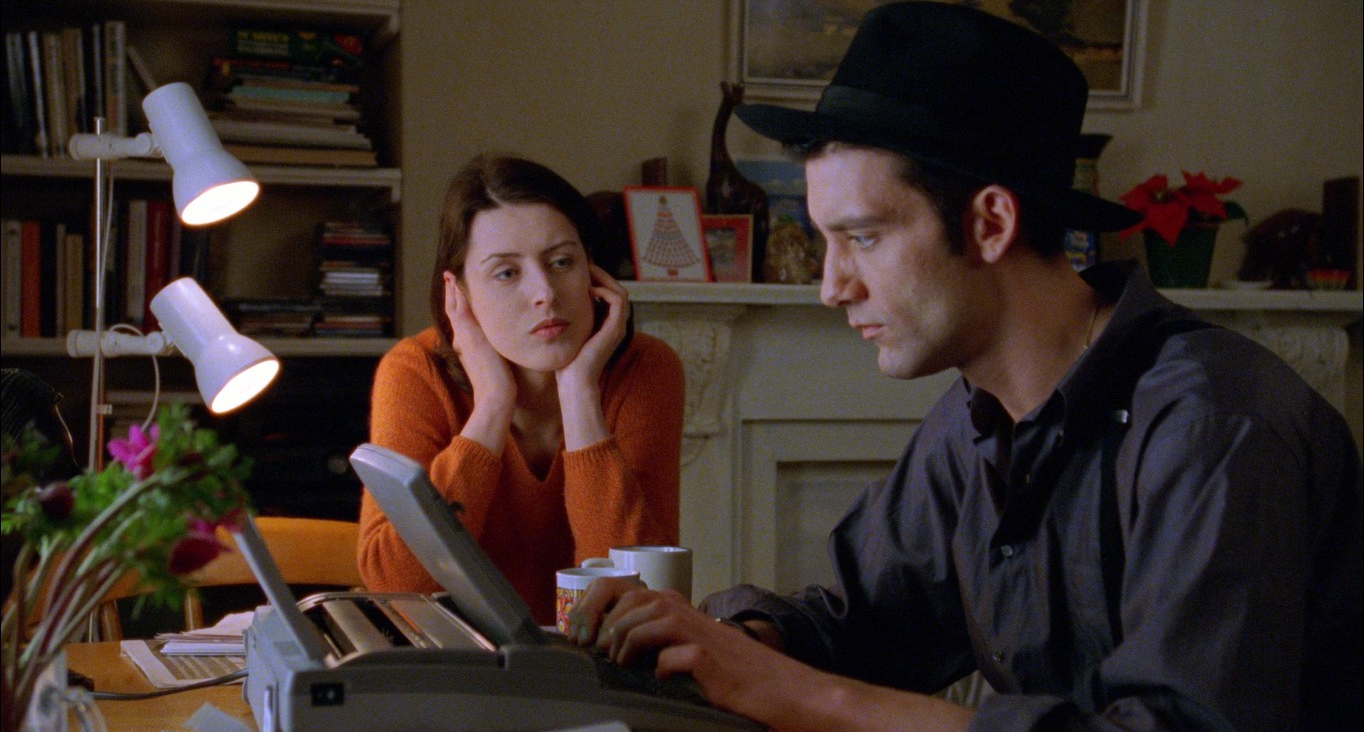

Jack Manfred (Clive Owen) is a struggling writer with literary aspirations for a novel he can’t place with a publisher. He lives with his fiancée Marion (Gina McKee), who’s attracted to the romance of living with a “sensitive writer” and her job as a department store detective supports them both. Jack is increasingly uncomfortable with being a kept man, however, so resorts to selling his 1957 Austin-Healey Roadster so he can back-pay his share of the rent for their basement flat in London.

Turns out the classic car had once been his father’s and selling it was also a symbolic act, shedding the baggage of his youth. Ironically, he’s dispensing with the car (a symbol of adulthood and independence) to assert his adulthood and independence. It’s the first step in a long-overdue rites of passage. We get Jack’s backstory piecemeal throughout the film, progressively enriching themes of self-discovery, and perhaps self-deception. It’s not at the fore, but there is a serious philosophical subtext concerning identity—how we define ourselves compared with how others see us.

When Jack meets publisher Giles Cremorne (Nick Reding) he hopes he may be in luck. However, it’s not Jack’s novel that interests Cremorne, who’s just after a ghostwriter for a celebrity football story that must include lots of corruption and plenty of sex. Jack’s belief that luck is for losers is confirmed and he abandons all hope for his novel… but then his past begins to catch up. Although Jack’s estranged ‘wheeler-dealer’ father (Nicholas Ball) is back in South Africa, he’s still pulling strings for his son and has set up a job for him at a casino.

At his ‘audition’ to be a croupier at the Golden Lion, Jack impresses the casino manager (Alexander Morton) with his cool professionalism and is surprisingly adept at the blackjack table and roulette wheel. We learn his father was an inveterate gambler whose habit drove away his mother and Jack was practically raised in the casinos of Sun City. As a result, Jack abhors gambling and gamblers, but admits to his own addiction… of watching people lose, night after night, while the dealer wields power over them. At the end of the day, the croupier always wins. Of course, he’s missing the point that he’s just an employee and the odds are actually stacked, steeply, in favour of the casino.

From this point, the narrative follows three parallel trajectories. The most obvious is a neo-noir crime drama complete with a tough-talking voiceover. Then there’s a treatise on relationships as we watch Jack deal, not only cards, but with the emotional scars of his upbringing. On top of all that, we get a metaphysical discussion about the meaning of morality in a society of winners and losers when the world doesn’t care which is which. Or, in the words of Ernest Hemmingway, whom Jack is fond of quoting, “the world breaks every one and afterwards many are strong at the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.” Clive Owen would later play the famous writer in Hemmingway and Gellhorn (2012).

Fittingly, the fat-free and focused screenplay is from a seasoned master of the craft Paul Mayersberg, who one can tell began his career as a film critic before moving into production. Working on The Masque of the Red Death (1964) gave him two important contacts in director Roger Corman, for whom he’d write The Tomb of Ligeia (1964), and cinematographer Nicolas Roeg, for whom he’d later script The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) and Eureka (1983).

Mike Hodges is just as eloquent in visual storytelling having turned his hand to nearly all genres. He started out in documentary television in the mid-1960s working on the current affairs programme World in Action before fusing documentary, travelogue, and children’s crime thriller in the quirky Thames TV serial The Tyrant King (1968), heralding his feature debut with Get Carter. Since then, his resume’s taken in gangster, science fiction, horror, comedy, and music videos for Queen—an off-shoot of his high camp reboot of Flash Gordon (1980), and supernatural thriller Black Rainbow (1989).

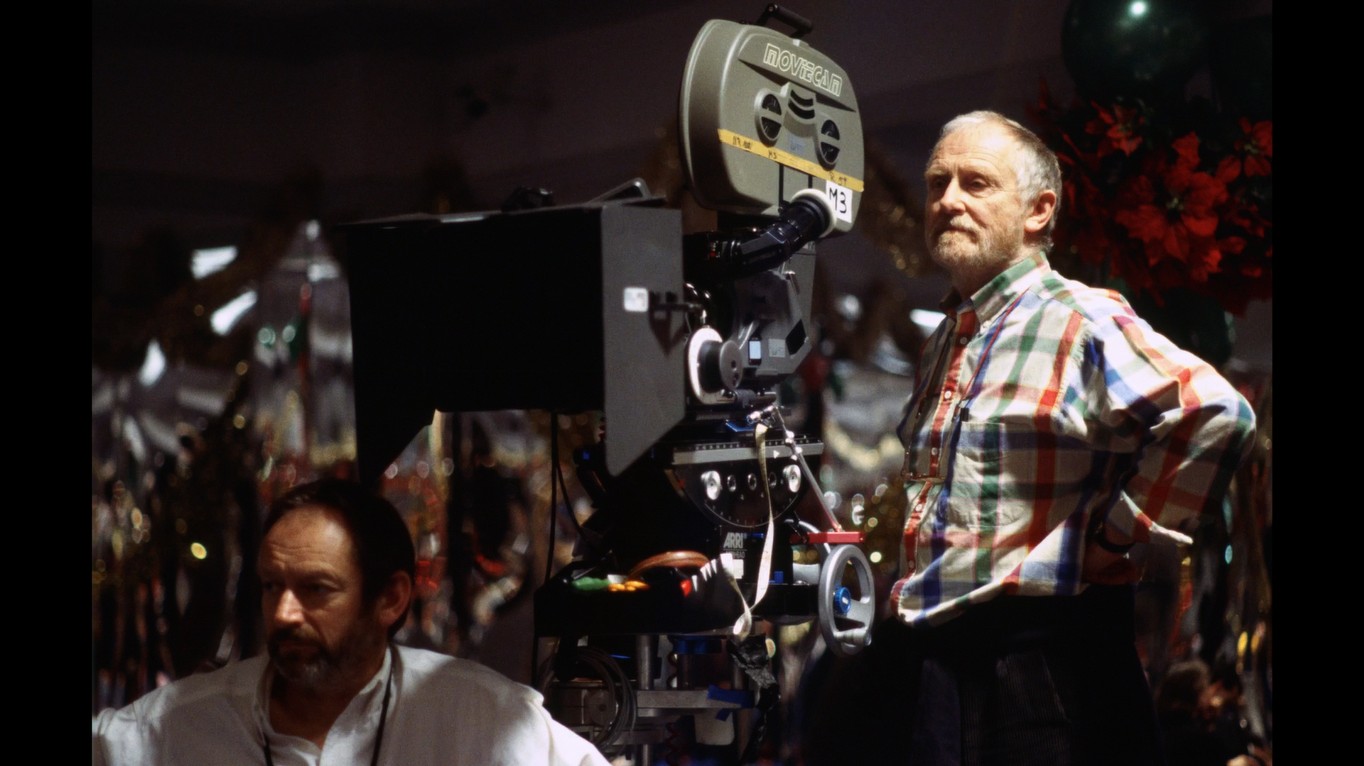

Here he’s aided by veteran cinematographer Mike Garfath, whose career also kicked off in the mid-1960s as Second Unit to Don Chaffey on Hammer Film’s One Million Years B.C. (1966), and to Stanley Donen on Arabesque (1966). He’d already worked with Hodges on Squaring the Circle (1984) and A Prayer for the Dying (1990). Garfath makes Croupier a visual treat, handling the night streets of London particularly well. The tacky tarnished splendour of the Golden Lion’s mirrored décor offers plenty of potential for distortion and clever visual metaphor but a challenge to keep cameras and crew out of shot.

We believe we’re inside one of those casinos that’s somewhere between sleazy last resort for the yuppies of the ’80s and playground for the ’90s newbie rich kids, although it was a purpose-built set at a German studio. So, when Jack enters the casino, he’s literally stepping into a world of artifice. He can’t admit that being a croupier is simply a job, to him it’s research. As he watches the workings of the casino and takes note of the desperate characters on the other side of the table, he works on a new novel.

From now on, the voiceover is laced with pastiche passages from the fiction playing out in Jack’s head, introducing another discourse comparing literate and visual storytelling that’s there for the cineastes to digest and consider the dichotomy of exploring the inner life of characters with a medium which can only show us their surface. It’s a problem that portrait painters have faced for millennia until cinema brought the added tools of actions and dialogue. The use of voiceover is also a cleverly contrived misdirection as we’re lulled into listening for the plot and may miss seeing the clues for ourselves. And as we should know, ‘actions speak louder than words’.

The boundary between fact and fiction begins to blur. He dies his hair black, slicks it down, and wears the croupier uniform of black suit and tie in everyday life, immersing himself in the character of his protagonist, Jake. His new, detached demeanour is so cool it’s cold. Owen’s performance has been compared with Alain Delon’s in Le Samouraï (1967), which may be no coincidence as Paul Mayersberg started his career on Jean-Pierre Melville’s earlier crime drama Le Doulos (1962).

Jack’s transition into an imitation of ‘Jake’, along with the unsociable hours of the casino, takes its toll on his relationship with Marion. He starts two-timing her with a fellow croupier, Bella (Kate Hardie), with an awkward and violent sex scene that crosses the line from the documentary realism of the first two acts into the somewhat cliched melodrama of the third. This is no accident and the narrative is painfully self-aware of the well-trodden tropes it now pulls together.

His unstable relationships with three very different women are clearly part of a doomed quest to find a mother substitute. The third is a down-on-her-luck ‘professional gambler’ whom he bumps into socially and then risks his job by having an illicit affair with a punter. It turns out Jack and Jani (Alex Kingston) have much in common, both being from South Africa, and it isn’t long before they’re embroiled in a plan to rob the casino…

For anyone genuinely interested in cinema and screenwriting, there’s plenty of fun to be had as Hodges effectively delivers a short course in scriptwriting. Croupier ticks all the boxes: introduce conflict to drive character interactions, thwart their desires, make them suffer, and force them to make the moral choices that drive the plot. This approach will also be a problem for some viewers who may well find the neat denouement just a bit too contrived. After all, Jack tells us throughout that he cannot abide cheats.

I saw the director’s cut of Croupier when Mike Hodges introduced it at a 1998 crime film festival in Nottingham prior to certification. It was the stand-out film of the festival and has stuck with me whilst all the others have faded from memory. However, despite plenty of positive reviews, it never garnered the interest of any distributor. It was granted a 15 certificate from the BBFC in 1999 with no cuts and its two prints only enjoyed a sporadic release on the British indie circuit. It was kicking around for a full year after completion before being picked up in the US by The Shooting Gallery, a smaller New York consortium that became an important supporter of indie film at the turn of the millennia.

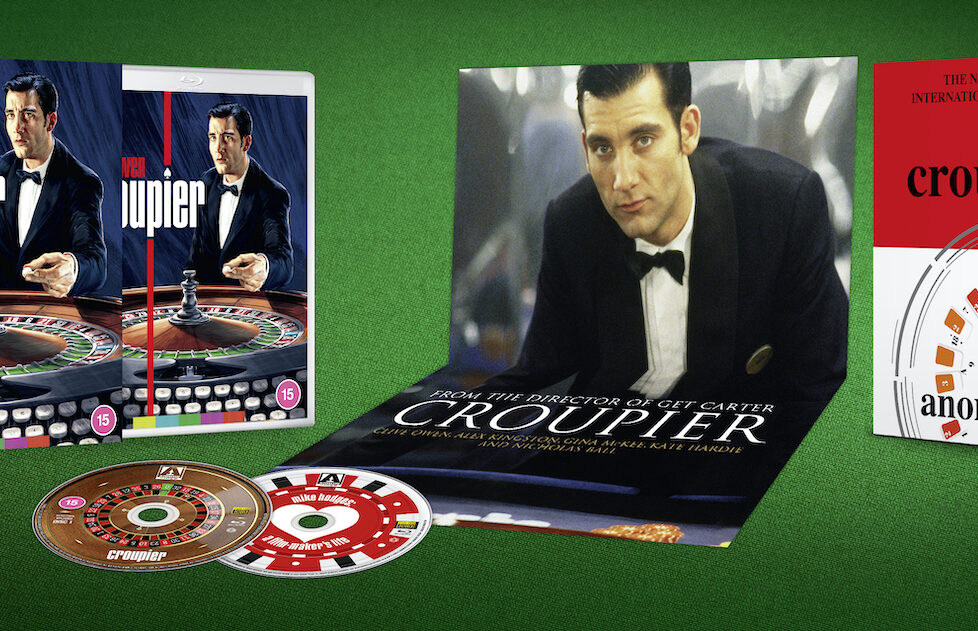

Croupier was their ‘sleeper’ hit of 2000. It eventually recouped Four Film’s £3M budget and ended up taking more than $7M at the box office. It was even touted as an Academy Award contender but disqualified as it had, during 1998, been given a two-week run at a cinema in Singapore and had apparently been screened on Dutch TV. According to the Los Angeles Times, Hodges and The Shooting Gallery hadn’t been aware of these showings until a publicist, for an unnamed rival Oscar nominee, tipped off the Motion Picture Academy of America (MPAA). Since then, it’s become an overlooked gem with the only home entertainment releases having around four minutes shaved off, presumably curtailing the aforementioned sex scene and perhaps two brief, but bloodily brutal, beatings. So, this brand new, director-approved 4K restoration from Arrow Films is a long-overdue and much-welcome release in both Ultra HD and Blu-ray editions. For anyone interested in Mike Hodges in the historical context of the British film industry, the extras include a bonus disc presenting a meticulous, two-hour interview with the director.

UK • IRELAND • FRANCE • GERMANY | 1998 | 94 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Arrow Video has also released Croupier on 4K Ultra HD, but the below was taken from the alternate Blu-ray release.

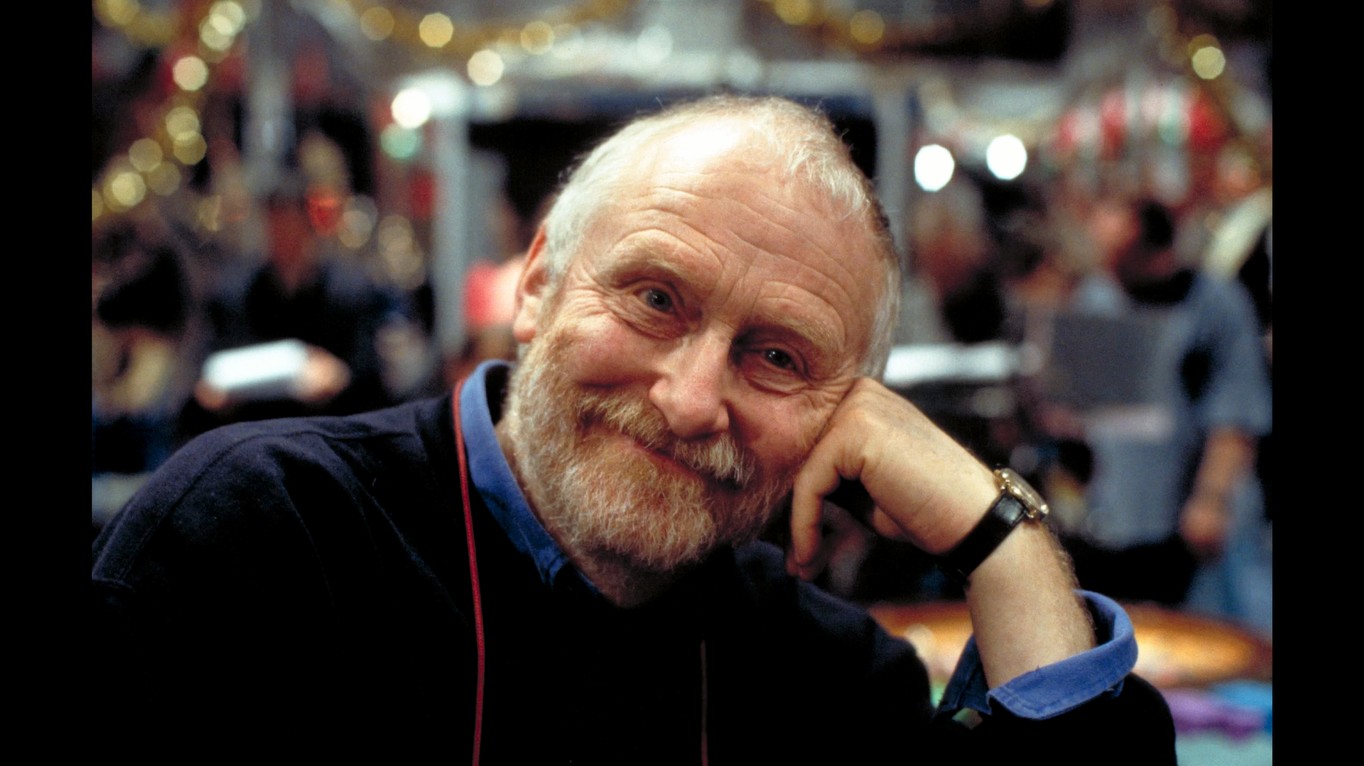

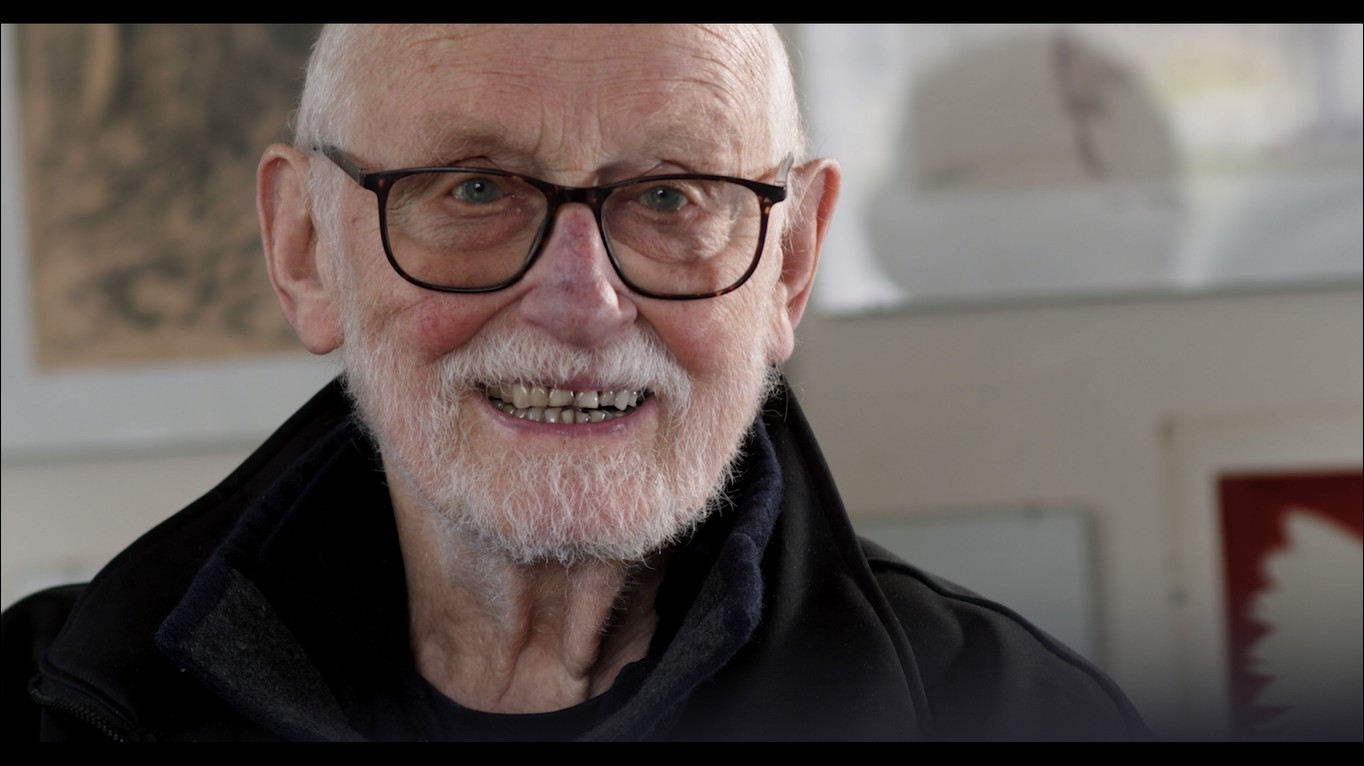

In this new, 121-minute documentary from Arrow Films, film critic David Cairns sits down with Croupier, Get Carter and Flash Gordon director Mike Hodges to take a closer look at the entirety of his career; featuring candid insights into the making of each film and his experience of the industry at large, it’s a remarkable portrait of one of Britain’s finest filmmakers.

At 90 years of age, Hodges shares rare insights, not only into his own long and varied career but into the history of British television and cinema—starting with his National Service in the Navy, qualifying as a chartered accountant, and then deciding to change career by entering the nascent commercial television industry and working his way up. He talks about how his military experiences, and then making documentaries for the World in Action series, shaped his political views in the ‘paranoid 1960s’.

Including plenty of personal anecdotes and biographical touchstones along the way, he talks us through a project-by-project chronology of his career starting with his initiative to make dramas on film for Thames Television, resulting in the inventive children’s series The Tyrant King, before making more experimental television films based on his own scripts, such as Suspect (1969) and Rumour (1970) for the ITV Playhouse series, The Manipulators (1972) for the anthology series The Frighteners, followed by Suspect, before his cinematic debut with Get Carter, and takes us through to I’ll Sleep When I’m Dead (2003), his most recent feature which also starred Clive Owen.

This is a fascinating couple of hours spent in the pleasant company of a passionate filmmaker. Insightful and surprisingly moving with moments of joy and poignancy. To end up with two hours of quality material from just over four hours spent with Mike Hodges is a testament to his eloquence and to the knowledge and interview technique of Cairns. Presented as a to-the-camera interview this feature-length bonus is the real selling point of the whole package.

director: Mike Hodges.

writer: Paul Mayersberg.

starring: Clive Owen, Kate Hardie, Alex Kingston, Gina McKee & Nicholas Ball.