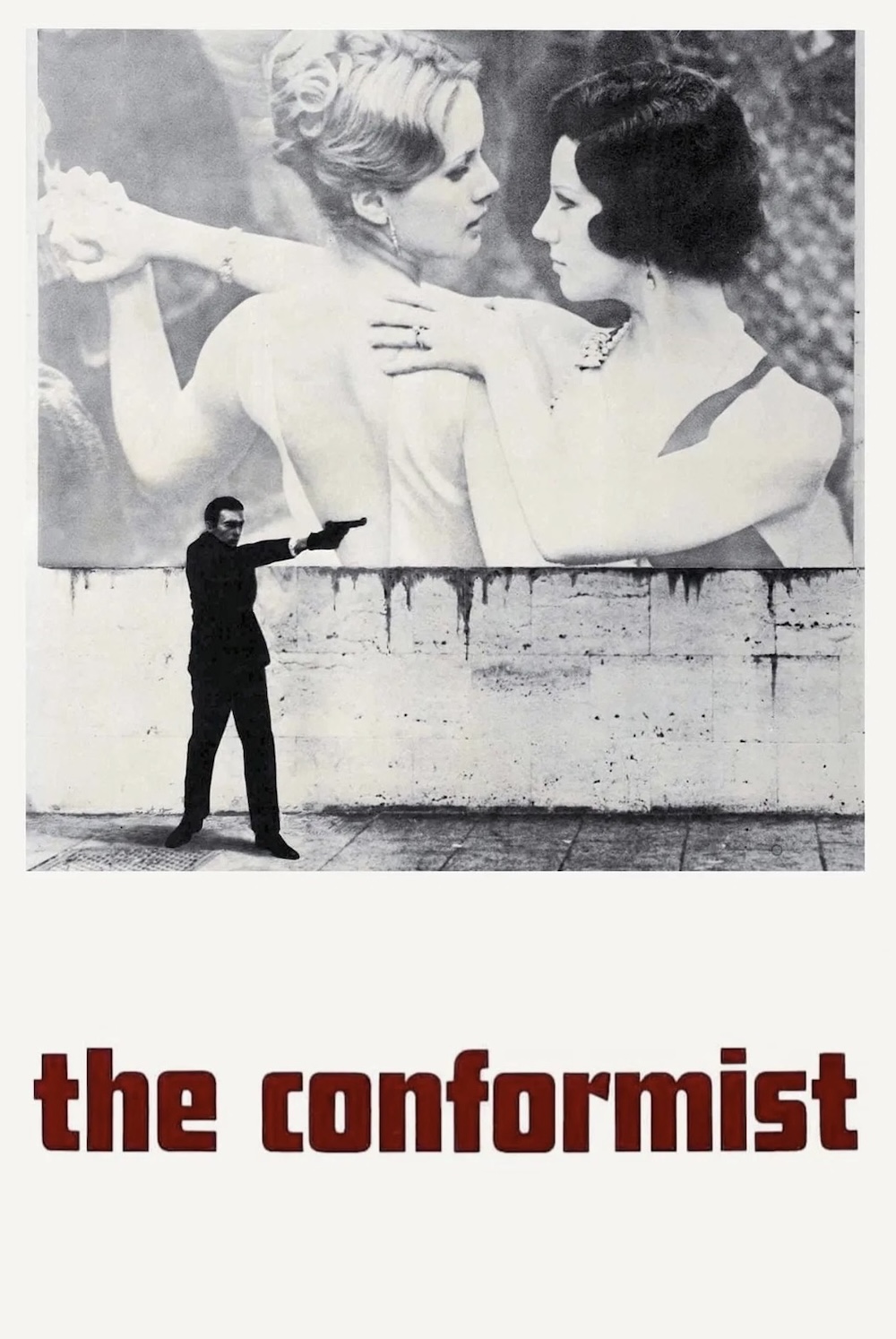

THE CONFORMIST (1970)

A weak-willed Italian man becomes a fascist flunky who goes abroad to arrange the assassination of his old teacher, now a political dissident.

A weak-willed Italian man becomes a fascist flunky who goes abroad to arrange the assassination of his old teacher, now a political dissident.

The saddest thing one can witness is the internal struggle of individuals repressing who they’re meant to be—the never-ending, painful process of having to hide oneself due to irrational, ignorant beliefs within our socio-cultural ethos regarding sexuality. Unfortunately, this outlook, brought to you by Abrahamic religions, has dominated our world and, more than likely, will never completely vanish as long as we continue to view religious texts as anything other than parables—a collection of shared symbols and archetypes repurposed to provide purpose in life and reinforce social unity and stability.

This desolate, dispirited feeling is more common than people think, as many struggle to accept their sexuality and live their lives promoting personas that are not their true selves—a lifelong act of self-deception, isolation, and agony. They view themselves as filthy, abhorrent, or monstrous—any adjective that could portray them as being beneath even the faecal matter of the lowest life form in existence, in their own eyes.

Many deny who they are outwardly, adopting an identity that castigates their truth, yet live truthfully where peering eyes can’t reach. Some who deny outwardly also deprive themselves of favoured flesh entirely and instead adopt a life that is deemed socially and culturally acceptable. Self-denial isn’t conducive to self-fulfilment and will always lead to projection of self-suffering until one can come to terms with who they really are. Cinema isn’t shy of filmmakers who employ this narrative focus in their work, whether singularly or throughout their filmography.

Claire Denis’ film Beau Travail (1999) immediately comes to mind, followed by Luca Guadagnino’s most recent film, Queer (2024). Both are remarkable films; however, the latter was greatly under-appreciated upon release. This may be attributed to the influx of fans Guadagnino gained after Challengers‘ (2024) release, who didn’t resonate with the filmmaking direction, as it did not align with what they’re used to—a presumptuous opinion to hold, seeing as these new fans have only seen one film from their new ‘favourite’ director.

Queer’s exploration of themes invites audiences to engage with the elements of the medium on a level that integrates them with emotional and psychological wealth, urging them to embrace the complexity of sexual identity, whether during a specific temporal moment or a broader context. Seeing Queer last year reminded me of a film that also synthesises the human condition with the specific rules of its medium: Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist / Il conformista.

Describing The Conformist as a masterwork of filmmaking would be disparaging. The Conformist exists in an echelon all of its own, above what many within the public consciousness of this artistic fandom consider some of the greatest contributions in cinematic history. Adapting Alberto Moravia’s novel of the same name and premise, Bertolucci forfeits some of the novel’s psychological profundity and backstory elements to successfully translate it to the silver screen, allowing the adroit visual elements of the film (cinematography, set design, lighting, and editing), when paired with the actions of its cast of characters, to facilitate what is missing by relying on the audience’s intuition. The way I see it, The Conformist is seamless visual poetry, one that defies the conventions associated with the typical cinematic character study.

Films of this genre focus on a singleton individual during a specific moment within their life so as to showcase the entirety of their, well, character: their personality, their aspirations, and elements of their psyche. They’re usually either a hero figure of some sort, equipped with qualities, idealism, and moral proclivity, or someone who lacks these elements and strives for their own personal interest (an antihero), cast against a backdrop of tremendous conflict of any variety (political, economic, social, you name it).

Great examples of this are Taxi Driver (1976), Scarface (1983), and There Will Be Blood (2007), as we bear witness to specific individuals attempting to define themselves within the context of the film’s world, one that usually parallels our own. The Conformist is the antithesis of this. Its protagonist, Marcello Clerici (Jean-Louis Trintignant), isn’t fuelled by power, greed, or beliefs, and he refuses to define himself as who he really is within this post-World War II backdrop; rather, he wishes to repress his truth and the trauma that befell his life in favour of socio-cultural normalcy defined by Italian fascism, as he views his truth and desires to be horrifically vile.

Clerici has homosexual urges—a truth he realised at a young age after a chance encounter that was both enlightening and terrifying. This defining moment has shackled him, causing him to constantly ruminate over different hues of dried ink and subsequently repress some of these instances back into his shadow, as it would anyone whose ego (Jungian) isn’t strong enough to undergo the process of individuation. These moments are presented beautifully, artfully, and seamlessly by Bertolucci’s approach towards the film’s structure: one of reflection.

Clerici sits in bed, fully clothed in professional attire, seemingly unable to sleep. The room is illuminated by the crimson incandescence of the fluorescent typography of the neighbouring business establishment. The tint flickers on and off, with moments of illumination and darkness lasting briefly before interchanging as Clerici sits, unable to remain still for even a moment while deep in thought. This solitary moment lasts until dawn, when Clerici receives a call from an anonymous person regarding a woman who has left with someone of importance, to which Clerici meets with this anonymous person out front of the hotel and leaves to intercept them.

Clerici looks worried, again unable to ease up, yet this time there is no indication of said feelings via his physical actions; it’s all in his eyes. Clerici is unable to focus on the driver’s words; he is recalling the moments leading to the now, which consist of his origins as a person, both of truth and of a false pretence, and the subsequent events that occur after the latter. Both types of recollections contrast and complement each other, as one could not exist without the other, yet the two couldn’t be farther apart on the socio-cultural/political spectrum.

One instance recalls a specific moment in Clerici’s life when he was joining the secret police and about to be wed. He speaks to his best friend, Italo Montanari (Jose Quaglio)—a man who is blind and a fellow fascist (clever)—of the rendezvous he has with the Colonel (Fosco Giachetti), to which Montanari enquires as to why Clerici wishes to be normal, like everyone else, when many people strive to be different. Clerici responds by telling the following story:

“Ten years ago, my father was in Munich. He told me that, often, after going to the theatre, he’d go with friends to a pub. There was a nut there, kind of a funny guy. He spoke about politics. He had become quite an attraction. They’d buy him a beer and encourage him. He’d stand up on the table, making furious speeches. It was Hitler.”

Given that both are fascists, with Clerici being an up-and-coming member of Mussolini’s secret police, this story can be seen as conveying admiration: that Hitler, someone looked fondly upon by those blinded by atrocious political views, was able to accrue public attention and subsequent praise by striving for normalcy.

However, this hint of reverence is only seen as such when taken at face value; the key is within its adjectives and can only be seen as such when Clerici continues to delve into his past, at a particular moment, not too far from this reflection, where he and his mother (Milly) visit his father (Giuseppe Addobbati) at the asylum. Castor oil had its uses back then, and they existed beyond aeronautic lubrication.

Through the shroud of pretence, wisps of Clerici’s truth exist, finding refuge within the words he utters, the volatility of his mood, and the fervour of his actions—a deeply intimate and intricately nuanced approach toward the shadow and its autonomy. Clerici not only hides his homosexual desires beneath the fascist socio-cultural norms of Italy but also the eccentric and empathetic elements of his personality.

These elements can be seen in slivers throughout the recollections in The Conformist, such as how he walks—short bursts of playful, euphoric skips—his humorous mocking of his mother, his embracing of those with pain in their eyes, and so on. And when even a hint of what he’s truly like is uttered by those who know him best, Clerici is quick to shut down said claim as a falsity.

The beauty of The Conformist exists beyond its recollective structure and its labyrinthine bosom of emotional and psychological wealth; it exists in its cinematography, set design, lighting, and editing. Vittorio Storaro’s camerawork in this film is profound, otherworldly even. The way the camera glides across the screen is seamless, occurring naturally and without making the audience aware of its existence, despite the design of each set facilitating multiple compositions within a single scene.

This is exceptionally difficult to do, as a set designed to facilitate multiple compositions within a single scene and allow the camera to glide across its confines freely defies naturalism solely because of how objects and structures are placed within the set—think of Wes Anderson’s work, for example. Somehow, the combined ingenuity of Ferdinando Scarfiotti (art director and set designer) and Vittorio Storaro surmounts the obstructions in creating an environment where new wave practices can thrive and simultaneously feel natural. It’s something else entirely—something I seldom see in films.

This feat in cinematic ingenuity is elevated further when combined with Vittorio’s use of lighting. In The Conformist, light is an active component that accentuates the dramatics of its narrative. Whether it’s the exterior light permeating between the gaps in the window blinds that move up and down a wall during a conversation between Clerici and his soon-to-be wife, Giulia (Stefania Sandrelli), or the light that casts a shadow off Clerici onto a wall during a rendezvous with someone he knew from his university days in Rome, Storaro’s philosophy of light speaks of a journey of discovery, reality versus falsity, and the uncertainty of whether Clerici wants to continue to live in the latter.

The marvel of The Conformist’s ingenuity extends to its editing—how it blends the present with the past, layering flashbacks upon flashbacks, bouncing to and fro to reveal veiled truths and create a nonlinear narrative that plays with temporality in such a lofty, seamless manner as to evoke Clerici’s feelings of anxiety, dread, horror, and uncertainty.

My favourite sequence of editing in the whole film involves Clerici, despite his atheist beliefs, undergoing a confession to proceed with his plans of conformity, marrying a “petty bourgeois,” as he puts it. The scene begins with Clerici, once again, sitting in the backseat of the car—a moment of recollection. It then proceeds to a flashback where Clerici confronts his sexuality for the first time, but this moment isn’t a pleasant one, as it scarred his psyche with fissures he just can’t seem to heal from.

Amidst Clerici’s delving into his shadow, the film cuts to Clerici in church in the middle of confession, as the church’s priest broadly enquires, allowing Clerici to delve further. It then continues back to the previous flashback, only for it to end in the church with Clerici alluding to the idea of socio-cultural conformity in front of the priest.

This sequence of events is a dual point of recollection. Clerici is recalling a moment in his past, then remembers recalling that exact moment somewhere ahead of it but still in the past—a recollection within a recollection where the shared memory lies between the two, capping both ends of this sequence with remembrance. It’s a highly creative structure of temporality that flows like butter and showcases Franco Arcalli’s prowess as an editor of Italian New Wave.

The Conformist is an astounding work of cinematic perfection in every single facet of its design and presentation. It focuses on a man in the midst of a crisis, a man who’s trying to come to terms with his true identity but is too much of a coward to do so, especially during this incredibly turbulent period of cultural disintegration and stifling conformity. Through his repression, Clerici hurts many by the immense friction brought about by the relinquishing of his independence and the autonomous nature of the shadow.

Remember, denying oneself the pursuit of recognition, connection, and intimacy can lead one towards a path of sovereign destructive behaviour and personal ruin. Stay safe and always be true to yourself.

ITALY • FRANCE • WEST GERMANY | 1970 | 108 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • FRENCH • LATIN • CHINESE

director: Bernardo Bertolucci.

writer: Bernardo Bertolucci (based on the novel by Alberto Moravia).

starring: Jean-Louis Trintignant, Stefania Sandrelli, Gastone Moschin, Enzo Tarascio, Fosco Giachetti, José Quaglio, Dominique Sanda & Pierre Clémenti.