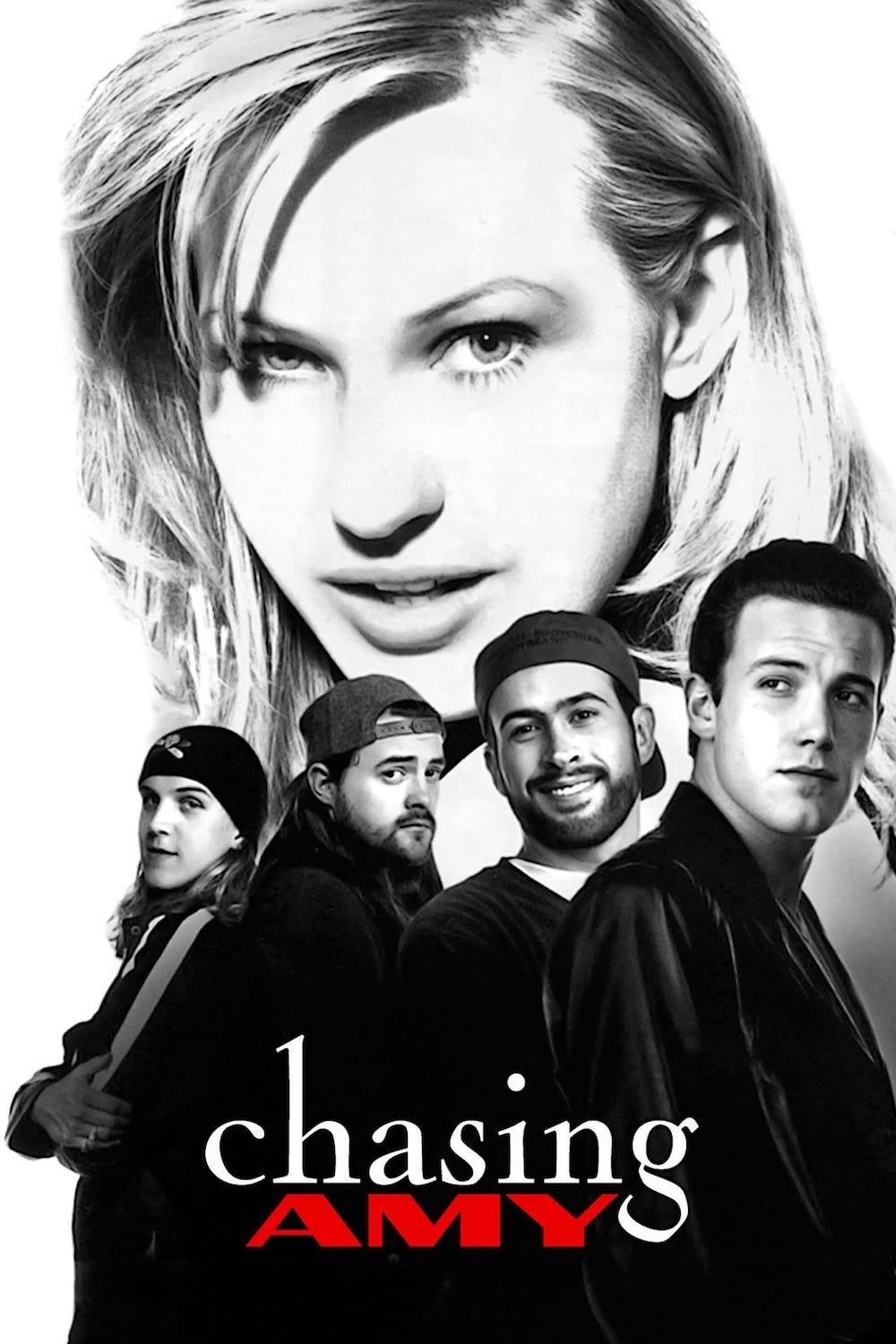

CHASING AMY (1997)

A comic-book artist falls in love with a girl he has a lot in common with, only to discover she's a lesbian.

A comic-book artist falls in love with a girl he has a lot in common with, only to discover she's a lesbian.

There are few filmmakers who better captured the anxieties of being a young adult than Kevin Smith. His debut resonated with an insecure and confused generation transitioning into adulthood, as Clerks (1994) showcased a sense of originality and raw innovation that blossomed from a shoestring budget of $27,000. It was a hilarious reflection of the jaded youth and attitudes of Generation X. The witty dialogue was remarkably crude and the characters engaged in interesting and authentic conversations. However, filmmakers that have an auspicious debut seem to have difficulties achieving sophomoric glory. Unfortunately, Mallrats (1995) was not as beloved by critics as its predecessor due to studio interference, as Smith later acknowledged on a DVD commentary, stating “they [Universal Studios] wanted us to make a smart Porky’s.”

Unable to replicate his debut’s propensity for crude humour and sexual gags, Mallrats wasn’t an immediate success. After its commercial failure, Smith realised he could no longer afford to alienate his loyal audience. Learning from the excesses of his sophomore effort, he instead returned to his indie sensibilities with 1997’s Chasing Amy, a vehicle for change and growth both professionally and personally. While maintaining his penchant for witty dialogue and entertaining characters, Smith found new inspiration in feelings of inadequacy. Combining his trademark pop culture references alongside wonderfully drawn characters, Chasing Amy became his most emotionally honest feature; an eloquently written rom-com that outshines other generic romances that permeated the 1990s. Grossing $12M at the box office, Chasing Amy was beloved by critics and is perhaps the peak of Smith’s career.

Set in New Jersey, best friends Holden McNeil (Ben Affleck) and Banky Edwards (Jason Lee) are enjoying success as the creators of the comic-book Bluntman and Chronic. While attending a convention, they meet fellow writer and artist Alyssa Jones (Joey Lauren Adams) promoting her own project Idiosyncratic Routine. Holden is immediately attracted to Alyssa… but soon discovers she’s a lesbian. But although he knows nothing can happen between them romantically, Holden decides to peruse a friendship with her, and as his Holden’s feelings for Alyssa develop he professes how he truly feels and Alyssa starts to question her sexuality as they become a couple. And this leads to Banky growing frustrated at the notion of losing his best friend to emotional adulthood.

The third entry in Smith’s ‘View Askewniverse’ tackles the complications of love and friendship in ways that remain relevant. Chasing Amy is more sophisticated than his previous work as it examines the emotional uncertainty of relationships and confronts sexual identity. Partially inspired by Scott Mosier’s crush on gay writer Guinevere Turner (American Psycho), the premise was based on Smith’s personal relationship as a means to express through a fictional story his jealousy and inadequacy. “The script really is one big apology to Joey Adams, because I was such a jealous prick,” he explained. “Making Chasing Amy saved me from being that guy for the rest of my life”. The filmmaker presented Miramax with his screenplay and a proposal for a $3M budget, but the studio would only approve it if he used more commercial actors such as Jon Stewart (The Faculty), David Schwimmer (American Crime Story), and Drew Barrymore (Charlie’s Angels). Uninterested in their proposition, Smith made a counter proposal with his own casting suggestions and secured a reduced budget of $250,000.

In addition to themes and locations common to his previous entries, Chasing Amy also reflects Smith’s penchant for working with familiar faces. When casting Chasing Amy, he called upon his first experience on Mallrats, joking “it was a six million-dollar casting call for Chasing Amy. I saw a lot of terrific actors I may have never met otherwise.” After impressing in Mallrats, Smith created the role of Holden with Ben Affleck (Deep Water) in mind. He recalls how “it was really in hanging out with Ben off camera that I discovered what a charming, insightful, and funny guy he actually is.” Affleck gives one of the earliest indications that he can be a genuinely good actor with the right material. Before effortlessly commanding a level of sensitivity and poignancy in Jersey Girl (2004), Affleck here delivers a layered performance as arrogant Holden, as he struggles to overcome his immaturity, insecurity, and deep-rooted fears that ultimately destroy his relationship. However, Affleck’s intense sincerity and genuine desire to grow makes the lovelorn character easily likeable and relatable.

Though Miramax had pressured Smith for an established female lead, the director fought to keep Joey Lauren Adams (Dazed and Confused). The actress hinted at endless potential in her limited role in Mallrats, displaying more depth than her character warranted on the page. Resembling a young Renee Zellwegger, Adams delivered a career-defining performance as Alyssa; a vivacious and seductive young woman taking the boldest step of her already adventurous life. Alyssa makes no apologies for her orientation or her past, and when she’s confronted by Holden her outbursts have startling intensity (“maybe you knew early on that your track was from A to B, but unlike you I wasn’t given a fucking road map at birth.”) What’s refreshing about the character is how she’s unlike most archetypal bisexual characters of the era—such as Basic Instinct (1992) and Single White Female (1992). Alyssa’s instead an ambitious, strong, and complex protagonist plagued by uncertainties over her sexuality. One can only assume many ambisexual viewers will be able to see aspects of themselves and their own difficult journeys. The actress effortlessly inhabits the character and her heartfelt performance would eventually garner the actress a Golden Globe nomination.

As a more vulgar and abrasive version of his character in Mallrats, Jason Lee (Almost Famous) is hilarious as Banky. Considering he’s not a professional actor, he manages to balance comedy with drama effortlessly. Banky resents his best friend’s blossoming relationship and fears what it could mean for his friendship with Holden. However, beneath the surface is a deeper meaning behind the character’s temperament. His homophobic slurs and jealously towards Alyssa are an extension of his own closeted feelings for Holden. That said, while Lee gets some incredible moments (“what’s a Nubian?”), his homophobic and obnoxious language will forever remain problematic. His character is perhaps the embodiment of toxic masculinity as he proudly exclaims his sexual exploits while debating the homoerotic undertones of Archie Comics. However, he also serves as a constant reminder of the person we could all become if we don’t question our own prejudices. When responding to accusations of homophobia, Smith commented “I didn’t make jokes at the expense of the gay community. I made jokes at the expense of two characters who neither I nor the audience have ever held up to be paragons of intellect.”

What begins as a comedy eventually reveals itself to be the most dramatic and emotional entry of Smith’s oeuvre. Chasing Amy perfectly balances humour and romance while maintaining the filmmaker’s idiosyncratic quips and inventive if uncouth dialogue. Most of the fun derives from Smith’s penchant for writing authentic conversations and realistic exchanges between characters. Similar to Quentin Tarantino (Once Upon A Time In… Hollywood), Smith’s scripts are packed with poetic monologues, rambling conversations, and pop culture references. A particular highlight is when Hooper (Dwight Ewell) protests against Star Wars for being racist during a comic-book convention. However, even when Smith allows his characters to express themselves naturally, he still manages to imbue his screenplay with moments of sincerity and honesty. During a pivotal scene, Holden expresses his hidden feelings to Alyssa, confessing “you are the epitome of everything I have ever looked for in another human being… there isn’t another soul on this fucking planet who has ever made me half the person I am when I’m with you… please know that I’m forever changed because of who you are and what you’ve meant to me.” It’s a testament to Smith’s writing abilities that he can write characters that can be naturally humorous yet display so much compassion and vulnerability.

Chasing Amy is undoubtedly one of Smith’s great accomplishments. He displayed a sense of emotional maturity that was absent in his previous work, resulting in an earnest and honest examination of fragile masculinity. There are unspeakable mistruths society indoctrinates in men to be masculine and Holden is unable to overcome these social stigmas. As Holden learns about Alyssa’s previous sexual relationships, he’s intimidated because he doesn’t want to be perceived as inadequate. His inability to comprehend his girlfriend’s past leaves him feeling insecure and he responds by sabotaging their relationship. Despite Alyssa’s assurances her previous experiences are in the past, Holden simply can’t overcome his insecurities. In perhaps the most famous scene, Silent Bob (Smith) offers Holden some advice, revealing he experienced something similar when he left his previous relationship after discovering his girlfriend’s promiscuity. Bob explains that he wasn’t disgusted with her, but was afraid because he felt small and inexperienced in comparison. He realised she was happy with him, but he ruined it due to his own fragile masculinity. It’s a poignant, emotional moment that reveals the fracturing of Holden’s manhood is something he must learn to comprehend.

What’s refreshing about Chasing Amy is that embraces promiscuity as it explores the misunderstood areas of sexual fluidity. Smith never judges Alyssa for refusing to succumb to society’s expectations and living on her own terms. She knows the difference between love and sex, ultimately choosing Holden because of their deeper connection regardless of his gender. In one scene, Alyssa explains she doesn’t necessarily need a man but she also won’t deny herself happiness. During a conversation with Holden, she explains “how seldom it is that you meet that one person who just gets you. And to cut one’s self off from finding that person, to immediately halve your options by eliminating the possibility of finding that person within your own gender… that just seems stupid to me.” She ends the conversation by saying, “I’ve come here on my own terms, and I feel justified.” Smith effectively introduces heterosexual viewers to bisexual and feminist perspectives, while challenging them to perceive relationships and sexuality differently. Admittedly, it may seem rudimentary when compared to contemporary LGBT features including Blue is the Warmest Colour (2013) and Appropriate Behaviour (2014), but Chasing Amy certainly prompted more sophisticated conversations and a better understanding of sexual identity that was relatively absent in ’90s cinema.

Unsurprisingly, Chasing Amy was greeted with a diversity of response amongst the LGBT community. Some lauded Smith’s honest and complex exploration of sexuality, while several academics (including Francesca Gaiba and Suzanna Danuta Walters) chastised the director for claiming that any lesbian can be turned straight if they meet the right heterosexual man. However, Smith received the most backlash for his depiction of the lesbian community and for portraying the characters as stereotypical misandrists. When Alyssa reveals to her friends she’s now in love with the dreaded male, they judge her for not conforming to their standards. The women are deeply disappointed and as one friend says while drinking her wine “Another one bites the dust”. However, as demonstrated in Rose Troche’s Go Fish (1994), some lesbians have certainly undergone identity crises and have become ostracised from their communities for similar reasons. Although Smith doesn’t articulate his ideas clearly, Chasing Amy does raise some interesting questions surrounding gay politics that remain pervasive today as they did 25 years ago.

Although Chasing Amy contains many elements of Smith’s previous output, his sincerity and humility proved that he’d matured as a writer-director. It’s a compelling introspective examination of fragile masculinity that also questions patriarchal standards of sexual relationships. Although it’s by no means a perfect portrayal of these issues, none of this would have been succeeded if it wasn’t for the incredible cast involved. Ben Affleck helps lift the material with perhaps one of his best performances, whereas Joey Lauren Adams aptly captures the emotional conflict of her character. Smith strikes a perfect balance between his idiosyncratic crass humour and genuinely thoughtful and observant philosophy. In a socially heated and fluctuating climate such as ours, Chasing Amy’s subject matter will always remain divisive. However, Smith understands that conversation is the start of the process of overcoming ignorance and tackles issues that many filmmakers avoid. In a decade that was oversaturated with romantic comedies, very few captured the insecurities of relationships like Chasing Amy.

USA | 1997 | 113 MINUTES | 1:85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Kevin Smith.

starring: Ben Affleck, Jason Lee, Joey Lauren Adams, Jason Mewes & Kevin Smith.