CATCH ME IF YOU CAN (2002)

An FBI agent pursues a charismatic young con artist across America and around the world.

An FBI agent pursues a charismatic young con artist across America and around the world.

By 2002, Steven Spielberg had spent a decade mostly directing films with a serious, even dark mood: Schindler’s List (1993), Amistad (1997), Saving Private Ryan (1998), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), and Minority Report (2002). The first two instalments in the Jurassic Park franchise were lighter fare, sure, but even they tried to pack some philosophical weight, delivered irritatingly by Jeff Goldblum.

When the director turned to adapt Frank Abagnale Jr.’s 1980 memoir Catch Me If You Can, then, the tale of a teenage conman was widely seen as a lighter, more trivial exercise; almost comic relief in Spielberg’s career. And yet, while Catch Me If You Can‘s style encourages a perception of it being superficial, it’s more complex than it looks and more solemn too.

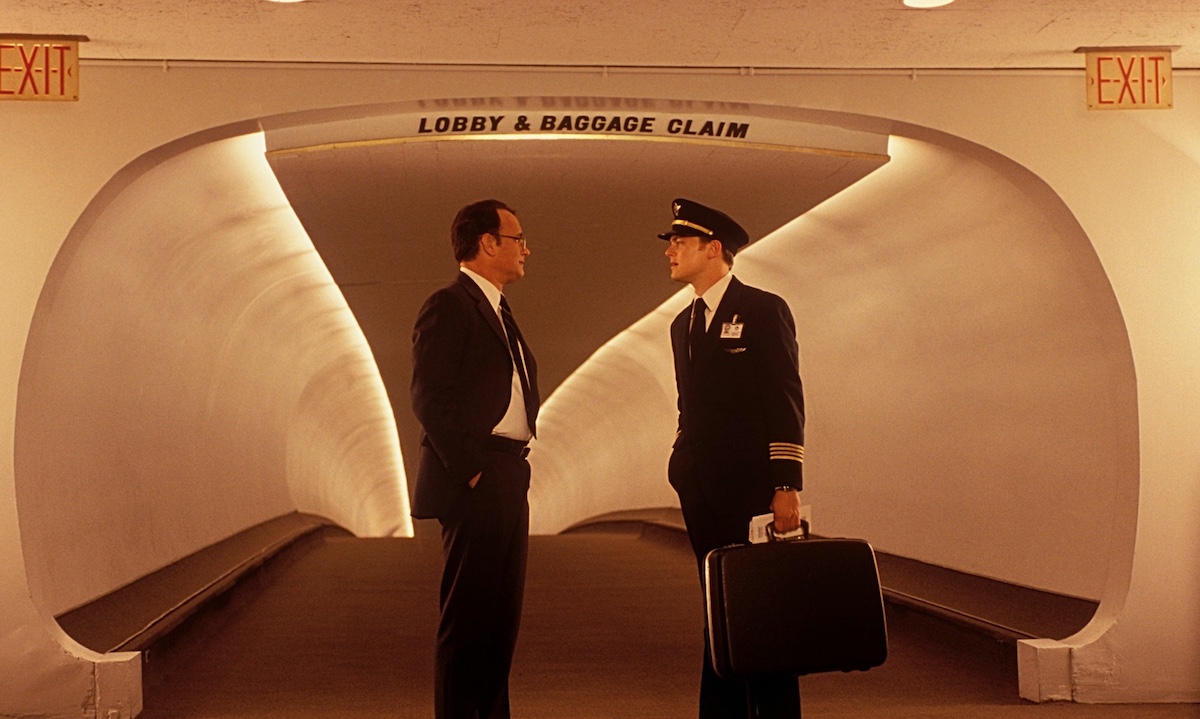

It opens in the way it will continue: presenting multiple versions of its central character, Abagnale (Leonardo DiCaprio). We first see him and two lookalikes on the US game show To Tell the Truth in 1977 (where contestants had to identify which was the real Abagnale and which the imposters), and then at a prison in Marseille in 1969. Here, FBI agent Carl Hanratty (Tom Hanks, playing a role based on a real agent of a different name) arrives to extradite Abagnale, shaggy-haired and sick after two years in grim confinement, back to the United States. It’s Christmas, the time at which many significant events in the movie will occur.

From Marseille, Catch Me If You Can skips back across the Atlantic to the small city of New Rochelle, New York, and back six years to the early-1960s. Abagnale is at a Rotary Club event with his father Frank Sr. (Christopher Walken); the latter, who owns a stationery store, is being honoured by the Rotarians. But the delight of both father and son at this triumph masks problems in the family; Frank Sr. is being aggressively pursued by the Internal Revenue Service over tax debts, and before long he and the boy’s French-born mother (Nathalie Baye) are divorcing.

The broken home is a familiar Spielberg trope (although he was a few important years older than Abagnale when his parents ended their marriage). And even before this, we might see other reflections of the director’s own life in Catch Me If You Can: when his father’s financial problems force the family to relocate from their comfortable home to a rather mean apartment, Frank Jr. also finds himself an uncomfortable fish-out-of-water at his new school, an episode that has been compared to the young Spielberg’s experience as a rare Jew in Gentile neighbourhoods.

More importantly for the progress of the film itself, it is at this school that he commits his first fraud: on the spur of the moment, he impersonates a substitute French teacher and takes a class for days before being unmasked.

This is little more than a prank, though, compared with what follows. Upon news of his parent’s divorce, Frank Jr. flees home and, now on his own, survives through con tricks; we see him paying for a train ticket using a cheque, the vehicle for many of his subsequent and more sophisticated crimes. (The cheque comes from a book his father gave him, symbolically significant: while Frank Jr. will go much further than Frank Sr. has in defying the law, the influence is clear.)

His early cheque frauds are not always successful, but he takes another bold step when he witnesses airline pilots arriving at a hotel (this at a time when air travel was glamorous and pilots were heroes) and, impressed by how respected—even adulated—they are, he decides he’ll pretend to be one too.

This is opportunistic, not part of any grand plan, and so will be his subsequent impersonations: acting the part of a hospital doctor (despite being nauseated by the sight of blood) and an assistant district attorney in Louisiana (to please the father of the girl he wants to marry, played by Martin Sheen). They’re more ambitious in scale than the young Spielberg’s reputed pretence at being an executive working at Universal Pictures, but similar in concept, based on clothes and confidence. “People only know what you tell them,” Abagnale says.

He’s not subtle: at one point he uses the pseudonym Frank Conners, and he’s still naive: awed by Sean Connery in Goldfinger (1964), he buys an identical suit to James Bond’s. At another time he calls himself Barry Allen, after the comic-book superhero The Flash. But he seems cautious about going too far; he acts as a pilot only to open doors and to obtain free air travel (eventually becoming known as the Skywayman), rather than to fly planes, and while posing as a doctor he doesn’t seem to treat patients directly, preferring the distance of a supervisory role.

Much of the interest of Catch Me If You Can through all this lies in the how rather than the who. We get little sense of Abagnale’s thoughts and feelings, but there is fascination still in the minutiae of his escapades: claiming to be a school newspaper reporter in order to interview a pilot and obtain inside information on his job, scamming an airline uniform from a supplier. He charms women, as well, both for information and for company.

Abagnale becomes more methodical and eventually sophisticated in his cheque frauds, too. Though his impersonations began as opportunism, his career of financial crime develops into a carefully planned one, and while Catch Me If You Can may never really let us into Abagnale’s inner life, there are tantalising hints here of his real drivers.

At the peak of his frauds, he’s accumulating more money than he actually needs, overflowing suitcases full; perhaps he’s just a product of consumer culture gone crazy, but perhaps he is also striving to compensate for his father’s own disappointments in life. Even after Abagnale has been apprehended, he will carry on emulating dad, delivering mail in prison just as Frank Sr. had joined the postal service after his tax problems forced him to close his business.

It goes both ways, too. At one point, when his son suggests giving it all up, Frank Sr. insists “you can’t stop!”. He lives vicariously through Frank Jr. and is enthusiastic that the boy is defying the federal government that has caused him so much heartache.

That is echoed in the next scene by Hanratty, the FBI agent, refusing to give up his pursuit of the elusive Frank Jr.: “I can’t stop,” he says. Not only is the story of Hanratty and his bank-fraud team a parallel one to the young conman’s throughout the film, but there is also a distinct feeling that they are acting out the roles of pursuer and pursued at the same time as forming an odd bond and that Hanratty is becoming a kind of second father figure despite Abagnale’s resistance to that idea.

The contrasts between father and son are mirrored in those between Abagnale and Hanratty—the federal agent passes the evening at the laundromat while the con artist spends the night with a model—and so are the similarities: when Abagnale and Hanratty talk on the phone one Christmas Eve, the FBI man initially wonders why his quarry is speaking to him, then laughs in realisation: “You have no-one else to call!”. Abagnale tells Hanratty where he is; Hanratty assumes it’s a lie, a false trail; but it’s not, it’s the truth. He half-wants to be caught.

Catch Me If You Can several times has to reiterate Abagnale’s youth as if we might be in danger of forgetting that DiCaprio—28-years-old when it was released—is playing a character a decade younger. Even the FBI initially assumed they were chasing someone in his late 20s. And there is a risk that we will forget; at times the character’s degree of self-assurance seems too much for his age, as do his forgery skills (though perhaps his father’s background in the stationery business helped). In appearance, though, DiCaprio fits the part—somehow seeming younger than he did in The Beach (2000) two years earlier, and believable even as a 15-year-old except in close-up. Toward the end of the movie, he then convincingly ages by a few years.

Abagnale is an ambiguous, ultimately unreadable character. His crimes are rather old-fashioned, seemingly victimless—as his mother says in his defence, “half the kids his age are on dope, throwing rocks at the police”— and Spielberg has compared him to Paul Newman and Robert Redford in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) and The Sting (1973): “They were breaking the law, but you had to love them for their moxie.” He somewhat resembles, too, the character that DiCaprio much later played for Martin Scorsese in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), which some thought guilty of glorifying crime. And yet there is also, in his assumption of different personas and his attraction to the high life, the faintest suggestion of the Versace killer Andrew Cunanan.

The screenplay may not delve into Abagnale’s depths, but DiCaprio’s performance does sketch them. Hanks’s character is an even more closed book, and even more tantalising for that reason; much like the actor’s lawyer in Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies (2015), Hanratty is serious, measured, and buttoned-up, but he clearly has a less controlled, more emotional self deep down.

It was Walken, however, who received the most accolades for his performance, nominated for an Academy Award (as was composer John Williams) and winning a BAFTA for his role in Catch Me If You Can, an unusually vulnerable one for the actor. Frank Sr. is a proud man—not least about his service in World War II; you can imagine him as a member of Hanks’s squad in Private Ryan—and an ebullient one on the surface, but an insecure and very worried one underneath.

Walken makes him one of the few truly convincing individuals in the film, although Baye as Abagnale’s mother comes close. Sheen, meanwhile, shows a gift for gentle comedy as the father of Brenda (Amy Adams), the young nurse who is alone in the world and nervous, like Abagnale, and falls for him; she might nominally be the movie’s love interest, but in reality, Abagnale’s family fulfil that function, and she is a little too close to stereotype.

While several critics found the pacing of Catch Me If You Can dragged towards the end, it was generally well-received as a slick, captivating diversion. “Catch Me If You Can is overly complicated in its flashback construction and too long for a movie that scarcely digs at all into its protagonist’s character… but still, it’s amusing and high spirited,” wrote Philip French in The Observer, while David Denby in The New Yorker concurred: “After the clenched seriousness of A.I. and Minority Report, Spielberg must have sensed that he owed us some fun, and the movie has a sleek and carefree look—the lightness of a ’60s comedy, made with the extraordinary speed and panache of our most fluent director.”

Indeed, the visual style of Spielberg’s film— shot as rapidly as its earlier acts move, in less than two months—is as far from portentous as could be. Sets are clean and uncluttered, colours are strong (becoming even more vivid as Abagnale’s criminal career flourishes, then receding again as he comes unstuck), the lighting feels bright even when it is dark; as Spielberg’s regular cinematographer Janusz Kamiński said, it was lit “like a glass of champagne”.

It has a choreographed feel, too, almost that of a musical (although Spielberg would not make one until West Side Story last year). Sunbathing girls turn over together on their poolside loungers in synchronised movement; a banknote twirls and coasts impossibly in the breeze as Hanratty approaches a door behind which he thinks Abagnale is hiding; the pair confront one another in a printing hall in France, Abagnale weaving around the huge machines in a duet-like scene. Most choreographed and musical-like of all is the sequence where Abagnale, in his pilot disguise, parades triumphantly through Miami airport with a bevvy of blue-clad stewardesses while FBI agents run in the other direction, chasing a red herring; on the soundtrack Frank Sinatra sings Come Fly With Me.

Passages like this can reinforce the idea that Catch Me If You Can is a trivial movie. So can the impression that is visually sunny throughout; that is not entirely the case, but it’s certainly the recollection that most viewers will be left with. So, too, can the superb but tongue-in-cheek opening titles designed by Oliver Kuntzel and Florence Deygas, depicting story elements in an abstract form and much influenced by both Saul Bass and The Pink Panther (1963); so, too, might Williams’s score. For this, his 19th movie with Spielberg, the composer delivers none of his famous big tunes but instead opts for a restless, elusive, skittering, jazz-influenced style—very appropriate to the subject—which just occasionally becomes ominous, and later wistful.

It would be a mistake, though, to imagine that Catch Me With You Can is pure froth. It would surely have been a much, much darker film in the hands of David Fincher—earlier lined up to direct—but even in its Spielberg form, the director’s biographer Molly Haskell has rightly described it as “melancholy-tinged”. While the tenor is often cheery and there is some overt humour to match (Abagnale fills a bathtub with souvenir model Pan Am planes, soaking off the logo labels to place on fake cheques), the pain of its lead character’s background is never far away. Nor is the suspicion that in assuming phoney identities he may be searching for his real one—also a concern of Spielberg’s A.I. and The Terminal (2004) around the same time.

Certainly, it’s true the movie slows and loses impetus toward the end, feeling like a different film and letting sentiment take too much control. That’s a problem because, however important it may have been to Spielberg, the emotional underpinning of Catch Me If You Can is never very engaging to the viewer; it’s an irony, perhaps, that a movie about a man who is always pretending to be someone else never itself reveals who he really is.

But it’s undeniably fun and one can’t help being captured by the costumes, the locations, Abagnale’s usually buoyant outlook, his unthreatening defiance of the law—and the details of the scams are interesting in themselves, too. And, though it’s difficult to see it as a major Spielberg work given its reluctance to probe too deeply into its characters, it gains an extra dimension when viewed in the context of his career.

It has another and supremely ironic aspect, too, when seen as a work not of Spielberg, but of Abagnale. Was he a master conman at all? Doubts had emerged about the veracity of his claims of a career of deception even before his autobiography was published, and it might have been a little dishonest of Spielberg and screenwriter Jeff Nathanson not to acknowledge these in the film, though it’s not clear whether this was deliberate or born of ignorance. Since then, in any case, more evidence has emerged to suggest that much of Abagnale’s story was made up.

So who is ultimately being conned by Catch Me If You Can: the audience or the filmmakers?

USA | 2002 | 141 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Steven Spielberg.

writer: Jeff Nathanson (based on the book by Frank W. Abagnale and Stan Redding).

starring: Leonardo DiCaprio, Tom Hanks, Christopher Walken & Martin Sheen.