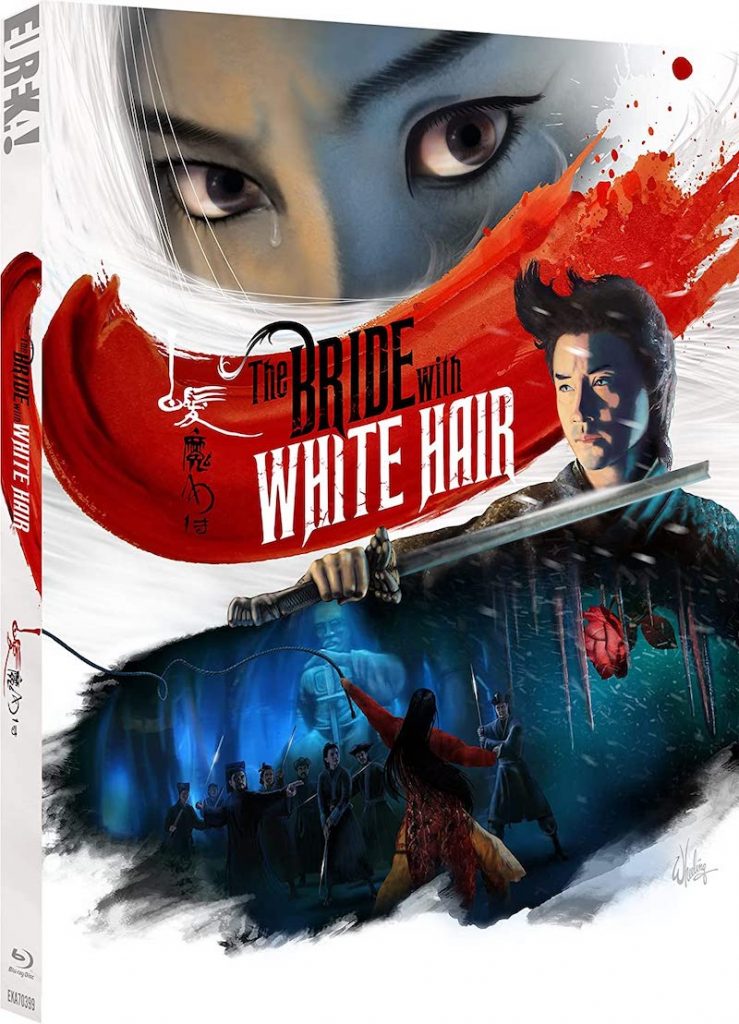

THE BRIDE WITH WHITE HAIR (1993)

Cho Yat-Hang, the unwilling successor to the Wu-Tang clan throne and the unsure commander of the clan's forces in a war against an evil cult, falls in forbidden love with Lien Ni-Chang, a killer for the evil cult.

Cho Yat-Hang, the unwilling successor to the Wu-Tang clan throne and the unsure commander of the clan's forces in a war against an evil cult, falls in forbidden love with Lien Ni-Chang, a killer for the evil cult.

The Bride with White Hair is a somewhat overlooked, yet formative, contribution to the wuxia revival of the 1990s. So, this newly restored Blu-ray from Eureka Entertainment may be considered overdue by genre enthusiasts, who should also be happy about the new extras accompanying this impressive package. The film’s 1993 release was perhaps overshadowed by Tsui Hark’s New Dragon Gate Inn (1992), which can be seen as energising the revival. Hark’s film, a remake of King Hu’s Dragon Inn (1967), which has long been considered one of a handful of wuxia films that defined the genre—along with Come Drink with Me (1966) and A Touch of Zen (1971), all directed by Hu. The wuxia genre can be summarised as mythic sword and chivalry, played out against a historic, rather than purely fantasy, backdrop.

The historic setting for The Bride with White Hair is suggested as the mid-17th-century, during the decline of the Ming and rise of the Qing dynasties. It’s based, quite loosely it seems, on the popular 1957 novel Baifa Monü Zhuan / The White-Haired Witch, by Liang Yusheng, which had already been filmed twice—as Story of the White-Haired Demon Girl (1959), an epic in three parts, and White Hair Devil Lady (1980).

Ronny Yu’s adaptation was in production during another period of national uncertainty. The Sino-British Joint Declaration had been signed in 1984; an agreement that the UK Government was to restore Hong Kong to the People’s Republic of China by July 1997. (A sort of mutually agreed and less destructive, Brexit.) So, to exploit this resonance, the timeline of the tale was moved a decade forward to place it near another time of turmoil and transition. Or, as writer Jason Lam Kee-To described it, “political foreboding.”

The once mighty Ming dynasty was overstretched and failing. There had been a series of harsh winters and dull summers, referred to as ‘the mini ice age’, so crops had failed. Add to this devastating floods and plagues across China. Unrest spread and the feudal lords stockpiled food for their armies whilst depriving their poor tenant farmers who’d produced it. A semblance of peace had been maintained between several clans simply because they were evenly matched, but the balance of power rapidly altered. Peasants began to rebel and clans were quick to take advantage of any weakening or lack of resources suffered by their neighbours. Eventually, two nomadic nations, the Mongol Empire and the Manchus, both vied to take control.

There were plenty of orphans and this film follows the fates of a boy and girl taken in and raised by rival clans. The young boy, Cho I-Hang, is played by actress Leila Tong (then aged 12 and known as Lina Kong), in what was already her fourth film before she became better known as a prolific television actress, currently appearing in the drama series Taan Sik Kiu / The Gutter. Cho I-Hang is trained in the way of the sword by the Wudang Clan—and yes, the famous rap posse Wu Tang Clan took their name from the same source. The Wudang Clan are a legendary Taoist sect that appear in many works of fiction, being a composite of several historic temples and kung-fu practices. Think of it like an Asian version of Camelot and the Knights of the Round Table.

The young Cho I-Hang is taught to value all life and gets lost one night whilst making his getaway after rescuing a goat from the butcher’s knife. The bleating of the kid attracts a pack of hungry wolves, but the boy can’t bear to abandon his charge in order to save himself. Miraculously, the wolves are called away by some haunting flute music and he follows, seeking its source, until he sees a little girl atop a rocky knoll surrounded by the wolf pack that have adopted and raised her. He then passes out from exhaustion and grows up haunted by this vision that may have been the dream of delirium.

The first act is, by far, the most successful portion, as it fully embraces the fairy tale aspects of the story and celebrates the expressionistic artifice of the sets and painted backdrops. There’s some lovely cinematography by Peter Pau, who would also work with Ronny Yu on the visually sumptuous The Phantom Lover (1995) and go on to truly shine with Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000)—the film that confirmed the global success of a wuxia revival.

We see the boy grow up in an extended montage as he learns the arts of calligraphy and combat. However, his teacher (Lok-Lam Law) has an ambivalent attitude to his most promising pupil. On one hand, he’s pleased with his astonishing martial arts prowess; but on the other, he resents him as a rival to his own daughter, Ho Lu-Hua, whom he hopes will one day take over as the first female head of the temple. By the time they’re adults, they are the most proficient protégés of the Wudang. Ho Lu-Hua (Kit Ying Lam) has a crush on Cho I-Hang (Leslie Cheung), but destiny has different plans for them both.

At this point, the film jarringly changes direction from a good-natured coming-of-age story into a bloodthirsty action film. Things get complicated when Cho I-Hang is caught up in the messy aftermath of a skirmish where troops mercilessly slaughtered a group of villagers who had stolen some rice to feed their children. Suddenly a mysterious figure robed in white appears and, literally, takes the soldiers apart, using a very long whip, almost joyously predicting how many parts each body will be cut into. I think nine bits was the best score!

Speaking of scores, Richard Yuen’s rousing music is probably the most consistently effective element of the entire film. It really underlines the repressed passions of the central characters and the tear-jerking moments only really work when Yuen highlights the emotional cues for us. He was fresh from writing the soundtracks for Swordsman II (1992) and Once Upon a Time in China II (1992), both directed by Tsui Hark and two of the finest examples of the wuxia revival.

After the massacre, Cho I-Hang is helping an injured woman give birth when the vigilante stops to lend a hand and inadvertently lets her mask slip. Although it’s been many years, Cho I-Hang recognises her and is certain this is the mysterious flautist who had once saved him from hungry wolves. He’s told that this is the infamous Lien Ni-Chang (Brigitte Lin). She’s also known as the ‘Demon Wolf Girl’, having been raised by wolves and later adopted into a barbaric clan who are now encroaching on Manchu territories. He realises then and there that she’s the girl for him! But how can that ever be as they are soon to be on opposing sides in war?

The ‘barbaric’ clan is clearly a stand-in for the Mongol hordes from the north of China, but here they’re portrayed as a mystic cult led by conjoined twin brother (Francis Ng) and sister (Elaine Lui), who use superstition and narcotics to keep Lien Ni-Cheng under their control. The conjoined twins camply relish their villainy and are depicted as monstrous, though one more than the other.

This is the outmoded trope of deformity signalling villainy. Whilst it may offend any conjoined twins in the audience, the existence of such twins with different genders is so rare as to be unheard of. Of course, in days of yore, anyone who was physically different enough to set them apart was to be revered or reviled, and burdened with superstitious ideas of divine retribution. So, as the story is set centuries ago, it’s likely those with strange physical attributes would have been marginalised and treated as ‘the other’ as a matter of course, without any form of informed debate.

The fact that one of them is given a sense of humour and shown to be an unwilling accomplice goes a little way to mitigating this lack of taste, but that wasn’t the only thing that got in the way of this working for me. As the twins deliver their dastardly lines and laugh maniacally, standing back to back, I just couldn’t help being reminded of Jessie and James of Team Rocket, comedic villains in the Pokémon animated series. I was waiting for Meowth to make an appearance! I wonder if these were the original inspiration? Don’t worry, if that means nothing to you, then it won’t detract from the movie.

There’s also some dodgy stereotyping in action here that hints at misogyny. Of the conjoined twins of evil, the female is portrayed as the more malicious and manipulative. To some extent, this echoes the relationship between Cho I-Hang and Ho Lu-Hua: I-Hang is a pacifist, who’d rather fend off armed adversaries using nothing but a bunch of reeds, as opposed to Lu-Hua who kills an unarmed peasant for accepting a gift that was too good for him! When it comes to war, I-Hang defers taking command of the Wudang army to Lu-Hua, whilst he and Lien Ni-Cheng attempt to escape the violence together…

There are many moments of brief, yet poetic beauty jostling with sillier scenes, gratuitous wire-work sequences, superfluous supernatural elements, and blood-spattering violence. One moment you may be smiling at the drunken antics of the young Cho I-Hang, then recoiling from the realistic aftermath of a battle fought with blade weapons—I mean, there are bits of bodies strewn across the screen!

No, The Bride with White Hair certainly isn’t boring. Not for one minute. But it never quite gels, leaving me ultimately unaffected and unsatisfied. Maybe it was the incongruity of serious emotional elements being too rapidly diffused by acrobatic combat and butting up against the comedic elements? Perhaps it was simply the predictability of the story that, once set in motion, just unravels to tragic inevitability. Perhaps one should cut it plenty of slack, though, as it precedes Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon by seven years!

The Hong Kong production and distribution company, Mandarin Films, had only been established for a year when they gave the project to director Ronny Yu. He was initially apprehensive as this would be his first foray into wuxia territory, which at the time was also out of fashion. When he read the popular novel, though, he was drawn to the romantic thread that tied sprawling historic events together and emotionally engaged him. Around the same time, he saw another film based on a popular novel that had reinvented its story by focussing on a doomed romance: Francis Ford Coppola’s luscious take on Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992).

Yu knew that the romantic angle had to be pushed to the fore and much of the political intrigue and historic details dropped. At the first script meeting, he told writer Jason Lam Kee-To to think of it as a reworking of Romeo & Juliet and simply described a ‘framing image’ of a young woman with white hair, wearing a wedding dress, standing atop a snow covered mountain. He offered no more guidance until the first treatment was complete.

Jason Lam Kee-To then collaborated with editor David Wu on writing the script as well as regularly checking with the novel’s author that they were remaining true the essence of the book. David Wu also envisaged the story spreading over two films and worked in plot threads he could pick-up in a sequel he was already planning. So maybe that’s why The Bride with White Hair doesn’t feel wholly satisfying then, because the end is not really the end..?

The Bride With White Hair Part 2 went into production almost immediately. Again Brigitte Lin and Leslie Cheung reprised their roles, but this time with David Wu at the directorial helm. Unfortunately, it does nothing to mitigate the pessimism of the first instalment and, what’s worse, isn’t included in this Blu-ray release! What a missed opportunity for a definitive release that would’ve really grabbed fan attention.

HONG KONG | 1993 | 89 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | CANTONESE

director: Ronny Yu.

writers: Ronny Yu, Lam Kei-to, Elsa Tang & David Wu (story by Liang Yusheng).

starring: Brigitte Lin, Leslie Cheung, Francis Ng, Elaine Lui, Yammie Lam, Joseph Cheng, Eddy Ko, Law Lok-lam, Pau Fung & Jeffrey Lau.