BRAZIL (1985)

Bureaucracy on film is a subject that, for obvious reasons, has always been best approached by filmmakers working under authoritarian governments, specifically in Eastern European countries in the middle of the last century. But with 1985’s Brazil, Terry Gilliam reminded us that bureaucracy is as commonplace in the democratic West as it is anywhere else. Of course, he’s not aiming for realism. This is a nightmare vision of a kind of future fascism that rules with consent and compliance from the population. Each interaction must be accompanied by the correct paperwork. Even a woman whose husband was mistakenly killed by the state is asked to sign a receipt afterwards before being told she can request a form if she wants to file a complaint.

Gilliam’s horror show is very much a capitalist nightmare, although its world’s evils are rooted in the reality we recognise around us. And despite now being 30-years-old, its impact and observations are more relevant now than they were then. From the first frame of the film, as a TV advert bumbles away in a shop window (even the medium carrying the advert is an advert), it’s made clear that this is not simply an allegory for the communist governments that still hadn’t yet fallen in 1985.

This dystopia is one beset by terrorists, and after each terrorist attack, a governmental player pops up on the television to discuss the reasons for such attacks and how the government is winning the war on terrorism. Those words will undoubtedly sound eerily familiar to anyone living in the West. But these terrorist attacks are so regular that they barely merit recognition. When a bomb goes off at a restaurant in which Sam and his youth-chasing mother are dining, they don’t even look up from the menu. Terrorism is reduced to a minor annoyance; it’s only consequence is the need to raise one’s voice in order to be heard across the table.

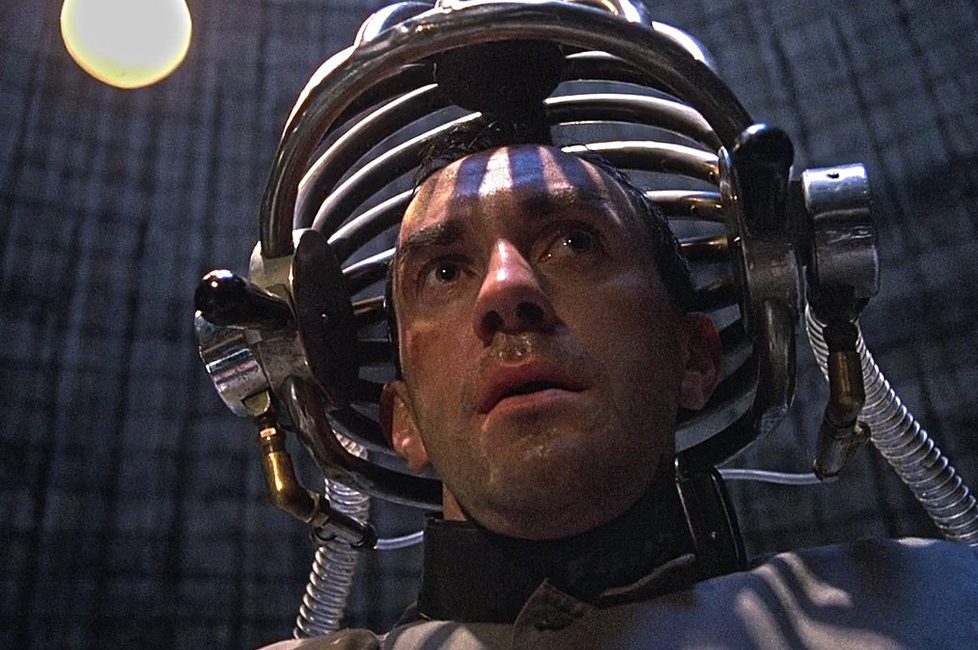

Sam Lowry, played by Jonathan Pryce, isn’t exactly a sympathetic protagonist. He’s no villain, but he’s little more than a heartless, emotionally-void piece of state machinery. In other words, the archetypal bureaucrat. What he does have are dreams; not in the sense of ambitions, but the kind you have when you fall asleep. In these dreams, he has a fuller head of hair, a pair of wings and the freedom to fly over green and pleasant lands—there’s no greenery at all in the real world of the film. Eventually, even his dreams abandon the freedom of open spaces and become trapped and confined in the corporatised, grey world of reality. The implication is that even his dreams aren’t free from the controlling hand of the state. As the dreams recur and progress, his alter-ego takes the shape of a revolutionary liberator, fighting the oppressors of a particular woman with a sword in his hand and a protective suit of armour.

Meanwhile back in the real world, Sam both enforces and battles, in his own much milder kind of way, the bureaucracy that constitutes his existence. Like in many a good dystopian movie, it’s a woman that catches the eye of the protagonist, dragging him out of his slumber and into a whole new world. It’s a well worm trope tracing back to George Orwell’s 1984. But where Orwell’s Winston Smith had already been flirting with rebellion before meeting his renegade beau, Sam is fully invested in the current order.

What I believe to be the most effective and creative denunciation of bureaucracy ever captured on celluloid comes quite early on in the film. Sam is experiencing problems with his air conditioning. Wanting the problem solved quickly, he contacts Central Services, the state body responsible for fixing such problems. This gets him nowhere though, so instead arrives a mysterious saviour played by Robert De Niro. His character is the total antithesis of the dominant ideology; he hates time-wasting, paperwork and regulations. He’s presented as the hero falling from the sky to fix the air conditioner and show Sam the worthlessness of the bureaucratic code he lives by. It turns out that this man is a terrorist, so it says a lot about the film that this fact doesn’t diminish his heroic status one iota.

Every scene is tinged with comedy; this isn’t a dry or serious dystopia. What the latest string of young adult dystopian fantasies lack is a single laugh—they could learn a lot from Brazil. Gilliam mixes together satire and physical humour. When Sam first meets his boss, he’s swept along in the marching pointlessness of the bureaucratic crowd. And when he arrives in his new office, the walls literally start closing in on him as the guy next door competes with him for space.

The history books are littered with examples of great films in conflict with Hollywood studios, and Brazil is just one of those examples. Gilliam had to take out a full page add in Variety magazine asking “Dear Sid Sheinberg, When are you going to release my film, ‘BRAZIL’?” because the studio cut the admittedly uncommercial film down to 94-minutes, giving it a happier ending in the process. No right thinking person would expect a happy ending from a film that paints such an unremittingly joyless and oppressive view of the world, even if it is graced by touches of comedic genius.

Brazil embodies that old cinematic conflict between art and commerce, and ultimately falls down very decisively on the side of the former: it was a commercial flop, but as good as anything to come out of Hollywood in its time. The most interesting idea the film posits is that the dictatorship of the future won’t be a scene of marching jackboots and enforced salutes; instead, we’ll slip into it, placated by trivial pleasures which make compliance the easiest option. It’s a believable thesis.

writers: Terry Gilliam, Tom Stoppard & Charles McKeown.

starring: Jonathan Pryce, Robert De Niro, Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm, Bob Hoskins, Michael Palin, Ian Richardson, Peter Vaughan & Kim Greist.