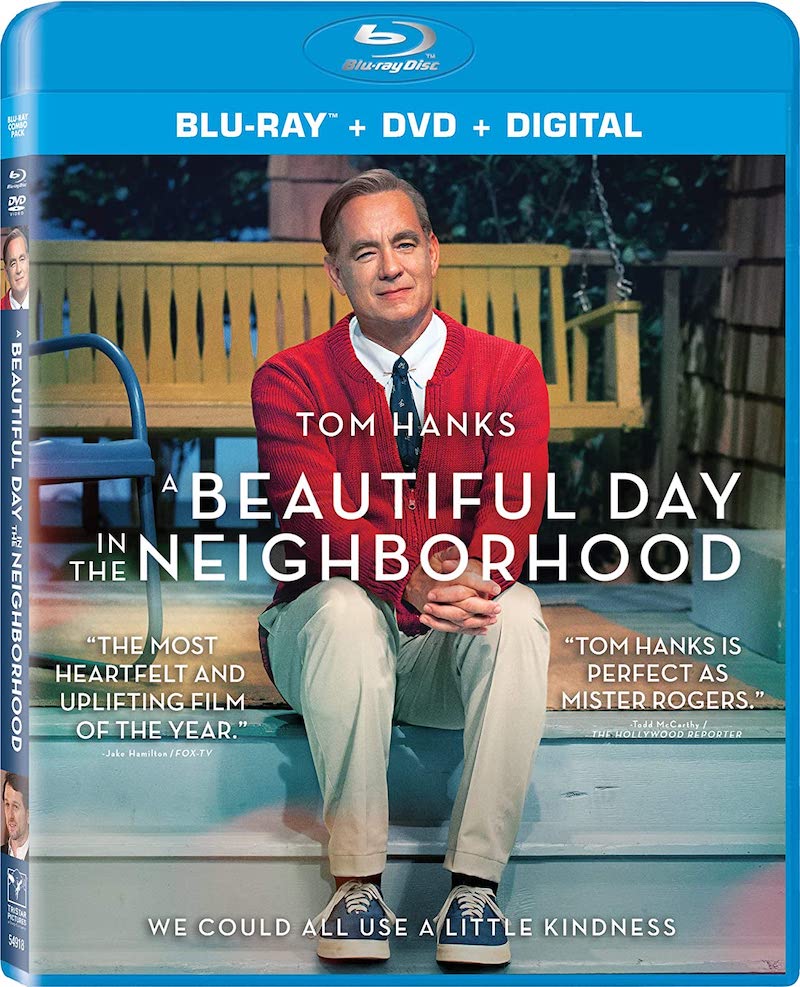

A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD (2019)

Based on the true story of a real-life friendship between wholesome children's TV entertainer Fred Rogers and journalist Lloyd Vogel.

Based on the true story of a real-life friendship between wholesome children's TV entertainer Fred Rogers and journalist Lloyd Vogel.

They say ‘never meet your heroes’, but there’s no such guidance for meeting other people’s heroes. How can someone inconsequential to you mean so much to someone else? How can a person who’s been no more than a passing thought be a modern-day saint to others? It has to be bullshit, right? This is the starting point of A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, a film less about the life of a US TV hero, and more about how these heroes factor into our lives and how we reconcile their appointed sainthood with the lack of grace in our everyday existence.

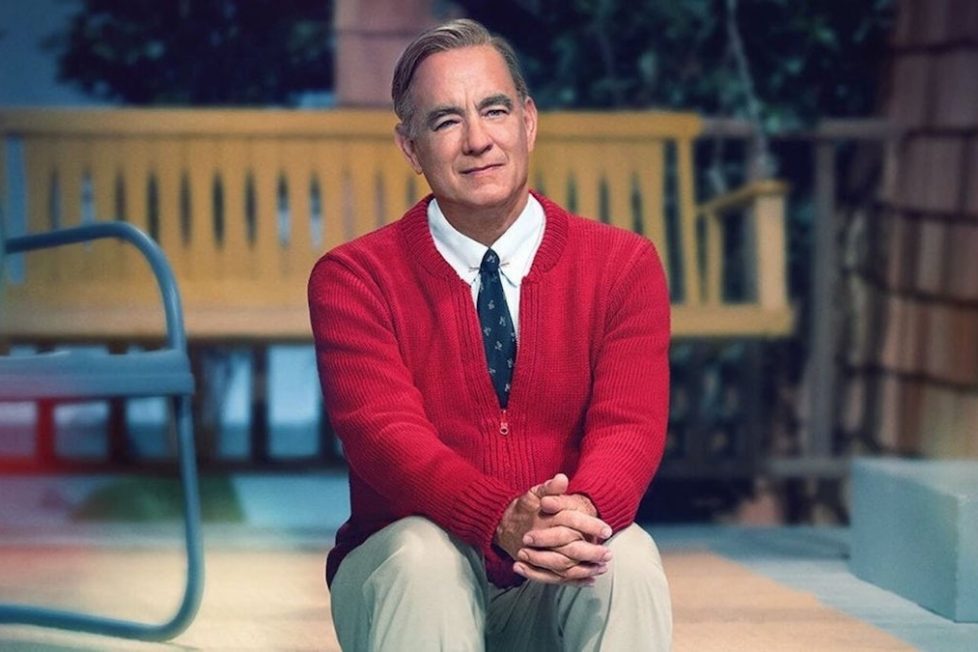

The film follows the true story of Esquire journalist Lloyd Vogel (Matthew Rhys) who’s sent to write a puff piece on Fred ‘Mr’ Rogers (Tom Hanks, the host of the beloved children’s educational show Mr Roger’s Neighborhood (1968-2001). It isn’t long before Vogel ends up emotionally involved in a story that’s as much about him as it is about his subject.

Director Marielle Heller explored another kind of artist in the superb Can You Ever Forgive Me? (2018), which similarly interrogated authenticity and wondered whether adopting someone else’s words can be a substitute for one’s own shortcomings. But in A Beautiful Day in the Neighbourhood, we’re presented with an artist who’s entirely authentic and doesn’t speak for an audience, but rather to them. There’s guidance, but no trace of creaking didacticism. Mr Rogers probably wouldn’t even think of himself as an artist. Artist implies performance, and thus disingenuousness.

There’s none of that in Heller’s film, which is richly human and generous. In keeping with her previous work, this is a movie sympathetic to the mistakes of human behaviour, making her out as a filmmaker ideally equipped to make a drama about someone like Fred Rogers—a figure of such benevolence and gentleness that Lloyd, a mercilessly cutting writer, can’t believe he’s for real.

Mr Roger’s world seems at odds with Lloyd’s. While Rogers exists in a neighbourhood of compassion, friendship, and most importantly communication… Lloyd’s world is defined by broken familial relationships, grudges, and impulsivity. When Lloyd’s estranged father (Chris Cooper) shows up to his sister’s wedding, it doesn’t take long for Lloyd to find an excuse to punch him. Lloyd falls back in with his sister, and his new brother-in-law reacts by punching him; it’s a chaotic moment of messy emotions and even messier reactions. Nobody stops to think ‘what would Mr Rogers do?’, but it’s a question that might serve them well. It might be a situation that Rogers could understand.

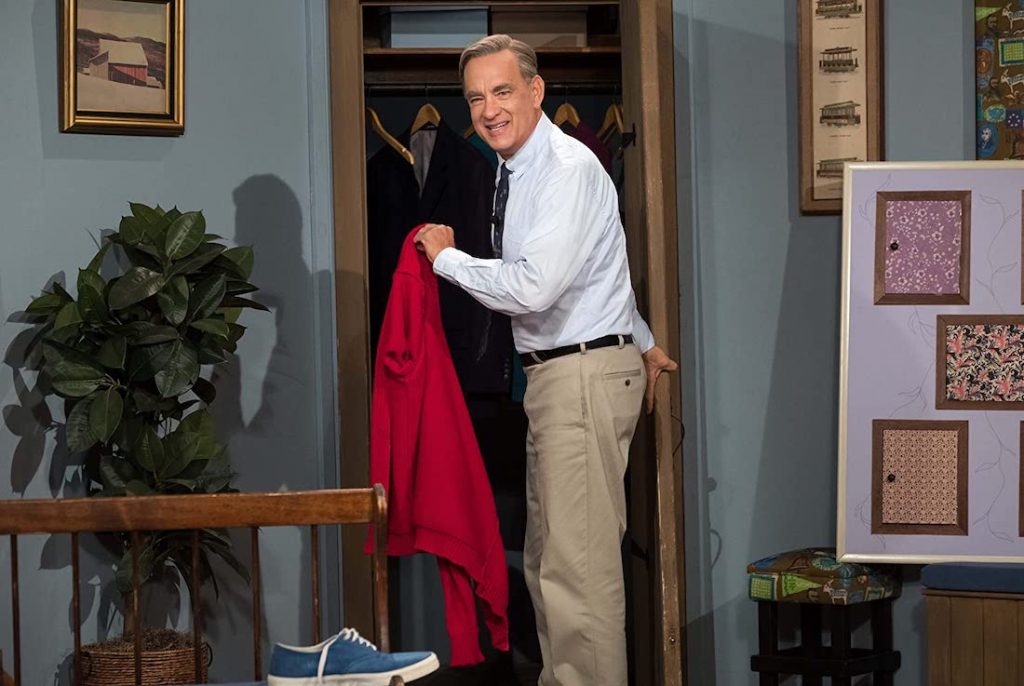

Heller keenly points out that Mr Rogers was no pie-in-the-sky idealist. He might talk softly, and his biggest daily concern seems to be ‘which sweater should I wear?’, but the world that Lloyd lives in is very much a part of Mr Roger’s neighbourhood, whether he likes it or not. A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, along with Morgan Neville’s wonderful documentary Won’t You Be My Neighbor? (2018) are careful to handle Mr Rogers with the weight and importance he treated everyone else with. The more the film listens to Mr Rogers, the more we hear what he’s actually saying.

Sometimes he might talk about not being able to erect a tent by himself, but what he’s really saying is that even an adult’s plans are fallible. He might talk through one of his puppet alter-egos about feeling upset, but what he’s really saying is that every emotion is valid and that children (or grown-ups for that matter) aren’t wrong for feeling them.

Rogers has the sort of plain-spoken wisdom that takes some sitting with before you realise how profound it is. When Heller gives his words the weight they deserve, it’s hard not to apply them to one’s own life. The crux of the film lies here, in Lloyd’s slow realisation that he might have found a father figure and a therapist all in one man. Heller beautifully illustrates these ideas by using miniature sets of cities, airports, and houses as establishing shots, suggesting that everything taking place in the film (and ‘our world’) can be seen through a Mr Rogers lens.

This is a crucial choice in the film. It soon becomes apparent this isn’t a film about an American Hero, it’s about the way in which we install heroes in our lives and draw strength from them. Even more intriguing is the question of whether our heroes are fictional or real! Someone like Mr Rogers seems to blur the line. Hanks’ performance, full of subtle choices that embody the man even if he doesn’t look like him, suggests that Mr Rogers was the same off-screen as he was on-screen. That genuineness and trustability catches you off guard and feels downright alien to behold now, in the 21st-century. It’s no surprise Lloyd feels like he’s being duped. Nobody is used to this sort of goodness without it being weaponised.

But as the film develops and as Lloyd reconsiders the way he treats his father and ignores his wife (Susan Kelechi Watson) and young son, it’s not Fred’s supposed purity that guides him. It’s his acceptance that every single person is imperfect and that being imperfect is okay, as long as we can talk about it. This is the principle that guides Lloyd, turning him inwards and forcing him to examine just how scared and confused he often feels and that feeling that way has to be ‘mentionable’. “If it’s mentionable”, Fred says, “it’s manageable.”

There are hints that Fred himself struggles, too. How could someone be so tuned in to human suffering without experiencing it personally? A brilliant touch comes during the film’s coda when Fred bangs the low notes of a piano, which earlier he’d described as something you could do when you feel bad. Why does Fred feel bad? We don’t know. This isn’t a film about him, really… it’s about the effects of a man like Fred Rogers.

The conversations between Fred and Lloyd are wonderful and their dynamic subtly changes, so it’s a shame the rest of the film’s relationships lacks the same intrigue. Lloyd’s struggle is unfortunately generic and vague, despite a strong performance from Rhys. What does work is what gets Lloyd to the point of changing his life, rather than the mechanics of how it plays out. In an age where TV show personalities sometimes mean more to us than our flesh-and-blood relationships, Heller understands the ways in which we live our lives under someone else’s philosophy…. and often that’s a TV or film character.

Particularly astute (and timely) is the subject of nostalgia and the suggestion that lessons taught to us when we were young (via the TV programmes that helped raise us,) will always be avenues we can explore again. They’re warm blankets we can pull over our feet; affirmations we can repeat. “What happened to you, Lloyd?” Mr Rogers asks with the sort of gentle authority that refuses to let you wriggle away easily. The question could be asked of all of us who grew up to become bitter and frustrated by real life. Now more than ever we slide into the childhood comforts that, at their best, not only seem to cherish us, but nourish us, and teach us how to navigate our lives now. What happened to all of us, we might wonder.

There’s no point to nostalgia if we don’t learn something from it. If we can’t find a way forward from looking back. If we simply want the sugar to go with the medicine, then it’s worthless reminiscing. The sugar and medicine should be the same thing, and this is what A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood is arguing. It’s a testament to the art that both comforts and feeds us, and to the power of cross-generational connections that can come from the circuit boards of a television or an unguarded conversation between you and a stranger. It’s these interactions that turn a stranger, whether it’s yourself, or a TV personality, into a neighbour.

USA | 2019 | 109 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

The disc provided for review didn’t contain the bonus material, but they’re as follows:

director: Marielle Heller.

writers: Micah Fitzerman-Blue & Noah Harpster (based on the 1998 Esquire article ‘Can You Say… Hero?’ by Tom Junod).

starring: Tom Hanks, Matthew Rhys, Susan Kelechi Watson & Chris Cooper.