THE ANDROMEDA STRAIN (1971)

A group of scientists investigate a deadly new alien virus before it can spread.

A group of scientists investigate a deadly new alien virus before it can spread.

On first viewing, in my early-teens, The Andromeda Strain profoundly impressed me. It was certainly one of the earliest films I watched that made me sit up and take note of the production crew as well as the actors. Robert Wise became my first favourite director! I’ve seen this movie a few times since, but not for more than a decade. So, watching this meticulously restored Blu-ray release from Arrow Video was a pleasant surprise. Not only are the picture and sound elements pin-sharp, due to a 4K scan taken from the original camera negative, but it’s also stood the test of time as a solid piece of filmmaking. And I think it’s even more engrossing than I remembered…

The opening scenes are as gripping as they come. A couple of soldiers arrive at a small New Mexico town to retrieve Scoop 7, a space probe that’s fallen back to earth after being knocked off course during its mission to collect samples from near-space in a search for extra-terrestrial organic material.

Much is made of distance and radio communications between the two soldiers and the Vandenberg Air Force Base heading the mission. They report that the town seems dead. Weirdly, there are innumerable vultures circling overhead, at night. They become increasingly agitated as they describe a scene of desolation and dead bodies before being abruptly cut-off as they report ‘something white’ coming toward them. It’s a narrative device we’ve seen many times since, some of the most memorable examples being the finale of Jeff Wayne’s War of the Worlds ‘rock opera’ (1977) and the slick sequence when the aliens pick off the Space Marines in James Cameron’s Aliens (1986).

The next day, Major Manchek (Ramon Bieri) at Scoop Control orders a reconnaissance jet flyby that confirms the town is littered with the dead and there’s nothing moving but vultures. He’s quick to call “a Wildfire alert” because of “unnatural death caused by Scoop 7 returning to earth”. Some great, enigmatic dialogue right there…

The enigma doesn’t let-up as we plunge into one of the most thrilling of non-action sequences. A group of armed ‘army-types’ knock on the door of a well-to-do house and call Dr Jeremy Stone (Arthur Hill) away from the reception he’s hosting. Matter-of-factly, they announce “there’s been a fire, sir.” Still one of my favourite moments in any film. The restraint with which the line is delivered and the moment of silent response before Dr Stone packs and leaves without explanation are powerfully understated.

There then follows a variation on the theme as the rest of a predetermined team of experts are assembled. It’s a fine formula that Michael Crichton, author of the original novel, would recycle a few times in more novels destined for big-screen adaptations. Secret teams of experts are called together at the start of Jurassic Park (1993), Congo (1995), Sphere (1998), and to a lesser extent Timeline (2003). It’s gone on to become a science fiction sub-genre in itself!

Dr Stone is a Nobel Prize-winning bacteriologist and the remainder of his team are pathologist Dr Charles Dutton (David Wayne), surgeon Dr Mark Hall (James Olson)—the closest thing to a ‘leading man’ we get here—irascible microbiologist Dr Ruth Leavitt (Kate Reid). The cast is spot-on and though not unusual for its time, seems refreshingly believable in their rather ‘normal’ appearance. Nowadays, there might be pressure to get a hunk and eye-candy in there to make the science feel sexier. But here the politicians look like politicians, the generals look like generals, and the scientists look and behave exactly like scientists.

Robert Wise had deliberately avoided casting Hollywood stars, as he’d thought that would spoil the documentary feel he was going for. There’re no A-listers, but all are veteran character actors with extensive and varied filmographies that prove themselves more than capable throughout. Even when they have to deliver the necessary exposition dialogue, they do it with aplomb and, for the most part, manage to make it seem natural. Well, as natural as explaining alien microbes and containment procedure can be.

The parts are primarily intellectual and don’t call for dramatic, emotional outbursts. The acting remains intense yet subdued as much is kept just under the surface. The scientists struggle to maintain composure and remain rational as they work round-the-clock against a deadly unseen foe. Some reviewers were critical of the amount of time they spend frowning at monitors, but even then the mood is maintained by an inventive score from composer Gil Mellé who mixes an array of noises reminiscent of old matrix printers, distant alarms and mechanised equipment to create a harsh rhythmic soundscape.

It transpires that Dr Stone had been a government advisor in the planning of protocol, should there be a serious biological threat, and on the design of a super-secret underground research base known as Wildfire. Its entrance is disguised as an agricultural research station somewhere in the Nevada desert.

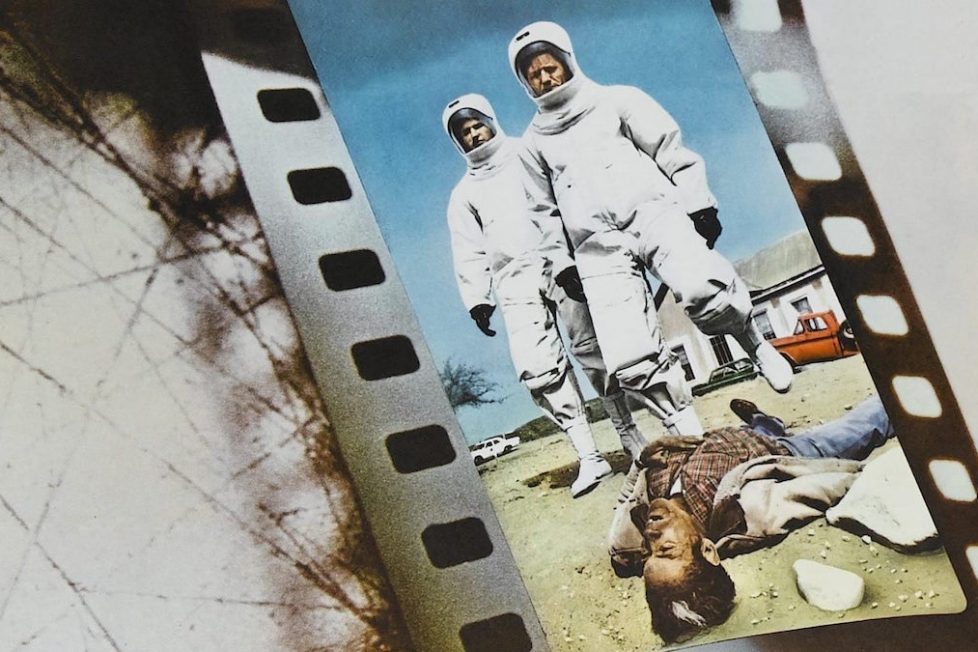

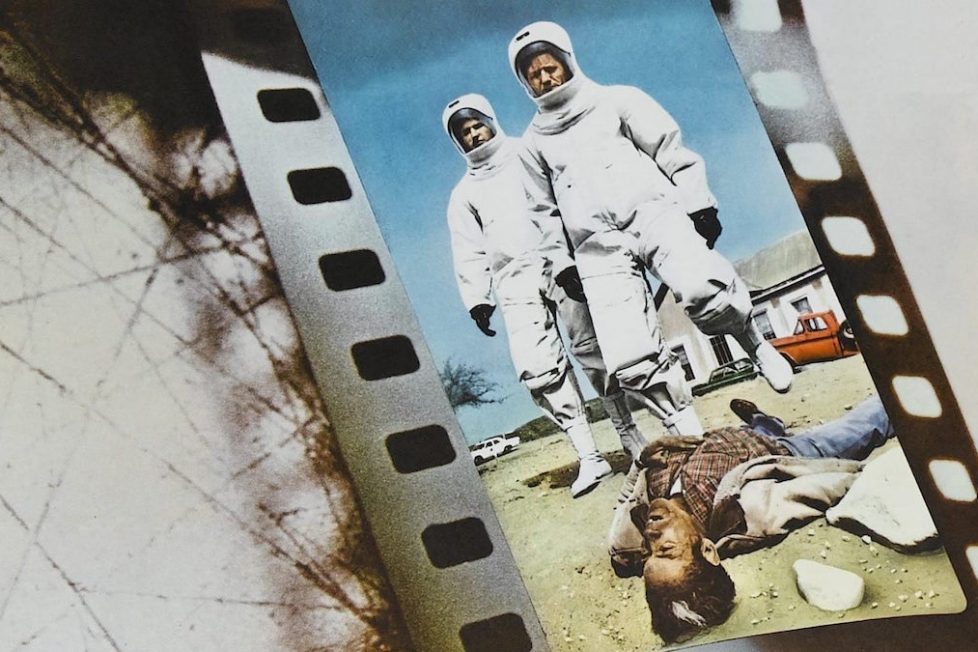

Stone and Hall don hazmat suits and bravely venture to the town of Piedmont, New Mexico, to locate and retrieve the contaminated Scoop 7. Although there is no gratuitous gore, this sequence pulls no punches and seemed far grimmer than I remembered—perhaps it had been edited for television?

The townsfolk all seem to have been felled mid-stride. Dogs and children lay where they dropped in the dusty street around the ball they were playing with. A woman has toppled to the paving, spilling her groceries. The postman sprawls on some steps. It’s an eerie scene reminiscent of the chilling photographs taken in those fake towns built in the desert where they tested the effects of nuclear bomb blasts. Only instead of mannequins, it’s the dead people scattered randomly about in a grotesque snapshot of everyday life, abruptly halted.

There’s an inventive use of split screen montage here, with the screen being divided into several frames at a time. This graphic, almost comic-book technique is utilised rather cleverly, later on, to fill in the main characters’ backstories with vignettes from their lives. Stone and Hall also discover that some of the citizens did not die quite as quickly and there were a few bizarre suicides. They also find out that all the blood in the dead bodies has been crystallised into a dry powder…

Then we get to see what the ‘something white’ actually was. Miraculously, an old man in his nightshirt is still alive and he, along with a baby are the only survivors. The scientists locate the space probe and take it, along with the survivors, back to the Wildfire base.

We’re about 40-minutes in when we finally get to the base, which is arguably the star of the show. The sets were built at the huge Stage 12 in Universal Studios where Robert Wise would also film The Hindenburg (1975) and which would also host the film versions of Crichton’s Jurassic saga.

For me, The Andromeda Strain sits best in the ‘artefact’ genre exemplified by 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Only here, instead of a mysterious Monolith of varying dimensions, the artefact is on the microscopic scale. That’s not the only similarity—the scientists briefly entertain the theory that the crystalline microbe may well be a type of alien tech intended to communicate and may even possess intellect.

The clean and clinical production design, particularly the curving corridors of the Wildfire base, have a very familiar aesthetic that reminds me of 2001′s Space Station V. Perhaps Douglas Trumbull’s presence in the visual effects department had some influence here as he also worked on the spectacular effects for 2001. He became one of the top visual effects legends, developing many new techniques including the revolutionary MagiCam system showcased in the opening shots for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). It’s estimated that $250,000 of the overall budget of $6.5M was used-up by Trumbull’s simulations of microscopy and his visualisation of interactive 3D computer displays, which wasn’t yet ‘a thing’ back in the late-1970s.

Just like his work on 2001, Trumbull was modelling and perhaps even helping to form a future that we enjoy as the present. Quite an achievement considering that what we now recognise as the PC wasn’t yet available. The screen interface we see in the film wasn’t launched until 1978 with the VisiCalc spreadsheet programme that took the PC beyond being a fancy electric typewriter. Trumbull worked with computer coder Jamie Shourt on creating the interfaces and the hi-res displays. I think there are several nods to Star Trek’s vision of the future, too. Indeed, some of the sets do look like they could be part of the USS Enterprise’s engineering sections, though more spacious.

Also like 2001, the pacing is assured and measured in the hands of an accomplished director. Today’s mainstream audience might find both films slow compared to the current style of cutting every few seconds. But sticking with it yields its reward. Whilst Kubrick’s 2001 ends with metaphysical bafflement, Wise handles the slow build of intense suspense consummately, ramping up the tension to a great ‘nail-biting’, or ‘nerve-shredding’, final act. I’ve said it before, Robert Wise is perhaps the most underrated of the truly great directors.

The isolation of the scientists in the hermetically sealed Wildfire underground base and the solitude of the crew in the Discovery One space vessel are both solid storytelling devices that distil and focus the action, taking a potentially global threat down to the human scale.

Wise was again working with his trusted production designer Boris Leven, whose set designs for his West Side Story (1961) had been awarded one of its 10 Oscars, which also included ‘Best Picture’. The sets for the Wildfire base give The Andromeda Strain its distinctive colour pallet and a clinical mood, which only serves to make the flesh-and-bone characters stand out even more. Having said that, the base is almost a character in its own right, complete with sensual computer voice and automated systems that work independently of human control.

It was adapted for the screen by another of Wise’s repeat collaborators, Nelson Gidding. They’d first worked together on the Oscar-nominated script for I Want to Live (1958), a docudrama starring Susan Hayward, soon followed by Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), a hard-hitting Brit noir starring Harry Belafonte, then again on spooky masterpiece The Haunting (1963) and historical disaster drama The Hindenburg.

Gidding made a few changes to the source material but remained faithful to the core concepts and central plot. One obvious change was changing the novel’s Dr Peter Leavitt into the female Dr Ruth Leavitt. This choice was initially resisted by Wise, who thought it may be a ploy to add a ‘decorative’ woman scientist and imagined something like the Raquel Welch role in Fantastic Voyage (1966). He acquiesced when he realised what Gidding had done to the part, making her the most abrasive, memorable and complex character of the group.

Michael Crichton had spent three years researching and writing the novel. It grew from his concern that humans were increasingly dabbling with dangerous science, both nuclear and biological. Whilst this could yield important discoveries that would benefit mankind, he also felt there were many risks involved and, should something go terribly wrong, contingencies had not been properly prepared. So, he wrote a cautionary tale that used the ‘generic’ threat of an alien microorganism as a metaphor for anything potentially apocalyptic, from nuclear fall-out to escaped bioweapons. He hoped the science fiction format would appeal to young scientists and subtly encourage them to better prepare for the, as yet unknown, threats they could unwittingly unleash.

America’s Library Journal hailed The Andromeda Strain as one of the most important novels of 1969 and it’s still regularly set as a study text in high schools and colleges across the US. The message is just as relevant today as it was back then, with the new CRISPR gene-editing technique and the potential ‘grey-goo’ end-of-the-world-by-nanites scenario (Google that one if you want—it’s truly terrifying!)

He had written a handful of novels under the noms-de-plume of John Lange and Jeffery Hudson (the name of a dwarf in the court of King Charles I—ironic as Crichton stood 6’9″!) The Andromeda Strain was the first he put his given name to. With pretty much unanimous critical acclaim, it topped the NY Times bestseller list for more than 30 weeks straight and turned out to be just the first in a string of hits. Suspenseful tales of science gone awry became his ‘trademark’ and many of his best-selling novels would be adapted into blockbuster films.

The next novel he wrote as Michael Crichton was 1971’s The Terminal Man, adapted into a 1974 film by Mike Hodges. Though it didn’t do nearly as well as The Andromeda Strain, it’s unusual and interesting, nonetheless. He then adapted and directed his own 1975 historical novel The Great Train Robbery, as the film starring Sean Connery, Donald Sutherland, and Lesley-Anne Down (1979). His 1976 novel Eaters of the Dead, inspired by the Viking Saga of Beowulf, was eventually filmed as The 13th Warrior (1999)—which although one of my personal all-time favourites never got the recognition it deserved. Crichton’s next novel Congo, a sort of up-dated King Solomon’s Mines, was also made into the eponymous 1995 film and, though critically slammed, was a fun romp that did good box office. Then came the aforementioned Sphere and, of course, Jurassic Park published in 1990, was adapted into Stephen Spielberg’s hit movie, as was Crichton’s sequel The Lost World, which served to inspire the second Jurassic movie.

It seems that Crichton’s technical research had been pretty extensive, and he’d already covered most of the bases to ensure The Andromeda Strain was believable. Wise and Gidding just had to make it all visually convincing. They sought advice from Cal-Tech and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab and sourced as much real scientific equipment and prototypes as they could, from several leading tech companies of the time.

They intended to make a sort of procedural science-fiction thriller in the style of a docudrama that would create suspense without stretching credulity. This they evidently achieved and the Infectious Diseases Society of America stated that The Andromeda Strain was the “most significant, scientifically accurate, and prototypic of all films of this genre… it accurately details the appearance of a deadly agent, its impact, and the efforts at containing it, and, finally, the work-up on its identification and clarification on why certain persons are immune to it.”

Now, here’s an example of sci-fi being spookily prescient! A few years after first watching The Andromeda Strain on television, I remember reading a scary article, in the December 1981 issue of Omni magazine, about a newly-discovered disease that sounded like something straight out of science fiction. The disease hadn’t yet been named, so it was referred to as ‘agent-x’. I’d learnt from The Andromeda Strain that a small virus is more than 100 ångströms in size, though the mysterious Andromeda agent had been about 2 microns—way too big to be a conventional virus and big enough to be a single-celled organism. Of course, it turns out to be neither.

Conversely, ‘agent-x’ had been shown to be less than 100 ångströms, perhaps as small as 50Å. That’s far too small to be a virus or any other organism that was known at that time. The medical researchers weren’t sure what it was, but could prove that it was transmissible, caused insanity or dementia and were ultimately fatal. It all sounded chillingly familiar! I can tell you, anxiety preyed on my teenage mind. I just hoped that somewhere like Wildfire actually existed and they were looking into it. As it happens there was. (Incidentally, contemporary with the film’s production in 1970, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a group of labs in Atlanta, Georgia, was so renamed and began taking the form we now know.)

Turns out ‘agent-x’ was prions—not true organisms but weird replicating protein structures. Stanley B. Prusiner of the University of California, San Francisco, eventually isolated the hypothetical agent in 1982 and his continuing research showed prions to be the cause of many fatal conditions including BSE, aka Mad Cow Disease, and variants of its human equivalent, Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease or KJD. The research earned him the 1997 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Recently, in May 2019, new research findings indicate that prions are key drivers in Alzheimer’s disease.

Now, if all that talk of fatal illness and degenerative conditions has made you feel ‘a bit funny’, then you have some insight as to how effectively chilling the concept behind The Andromeda Strain is. It’s hard science fiction, sure, but also pushes some horror tropes that we’re now more used to seeing in zombie movies. It’s no coincidence that the zombie virus in The Walking Dead was codenamed ‘wildfire’ in homage.

Hypochondriasis, the fear of disease and contagion, was exploited in George Romero’s Of The Dead trilogy, starting with Night of the Living Dead (1968) in which it’s tenuously suggested the zombie outbreak may be the result of a space probe bringing some form of radiation back to earth… I suppose that idea was prefigured by Nigel Kneale’s The Quatermass Experiment BBC TV series (1953) and subsequent Hammer Film Production (1955). But the contagion of The Andromeda Strain is more bluntly frightening than a zombie invasion. It either kills you in seconds or allows a few minutes for insanity to set-in and inspire bizarre suicide. You can’t hide from it. You can’t see it coming. You can’t drop it in its tracks by putting a bullet in its brain.

The Andromeda Strain’s vision of state-of-the-art tech was inspired and remains convincing, though it’s also clearly 1970s futurism. It would fit into a nice classic sci-fi box set along with The Forbin Project (1970), Demon Seed (1977), Altered States (1980), and perhaps Endangered Species (1982). Its themes and iconography resonated through to the blockbuster Outbreak (1995) and currently in National Geographic’s TV drama series The Hot Zone (2019).

It was remade as a TV miniseries in 2008, adapted by Robert Schenkkan, a screenwriter and actor I remember as the ambiguous Lieutenant Commander Dexter Remmick in two Star Trek: The Next Generation episodes from 1988, “Coming of Age” and “Conspiracy”. It seems he remained fairly faithful to the original storyline, but padded it out with backstories and added a Star Trek-style time-slip that implied the Andromeda Strain was indeed an intelligent microorganism that had been sent back from the future. This time it was directed by Mikael Salomon, who was also behind the miniseries remakes of Salem’s Lot (2004) and Coma (2012). I haven’t seen his version and don’t particularly want to. It did fairly well in terms of viewing figures and was nominated for several Emmy Awards. Inevitably, it also gathered plenty of poor reviews that compared it unfavourably to its cinematic predecessor.

Although Crichton’s original story seemed to hint at a possible follow-up, it never materialised. So, taking his cues from the issues it raised, novelist Daniel H. Wilson has now written a sequel, The Andromeda Evolution, scheduled for publication this November.

601 – DISENGAGE – END PROGRAM – STOP –

director: Robert Wise.

writer: Nelson Gidding (based on the novel by Michael Crichton).

starring: Arthur Hill, James Olson, Kate Reid, David Wayne, Paula Kelly & George Mitchell.