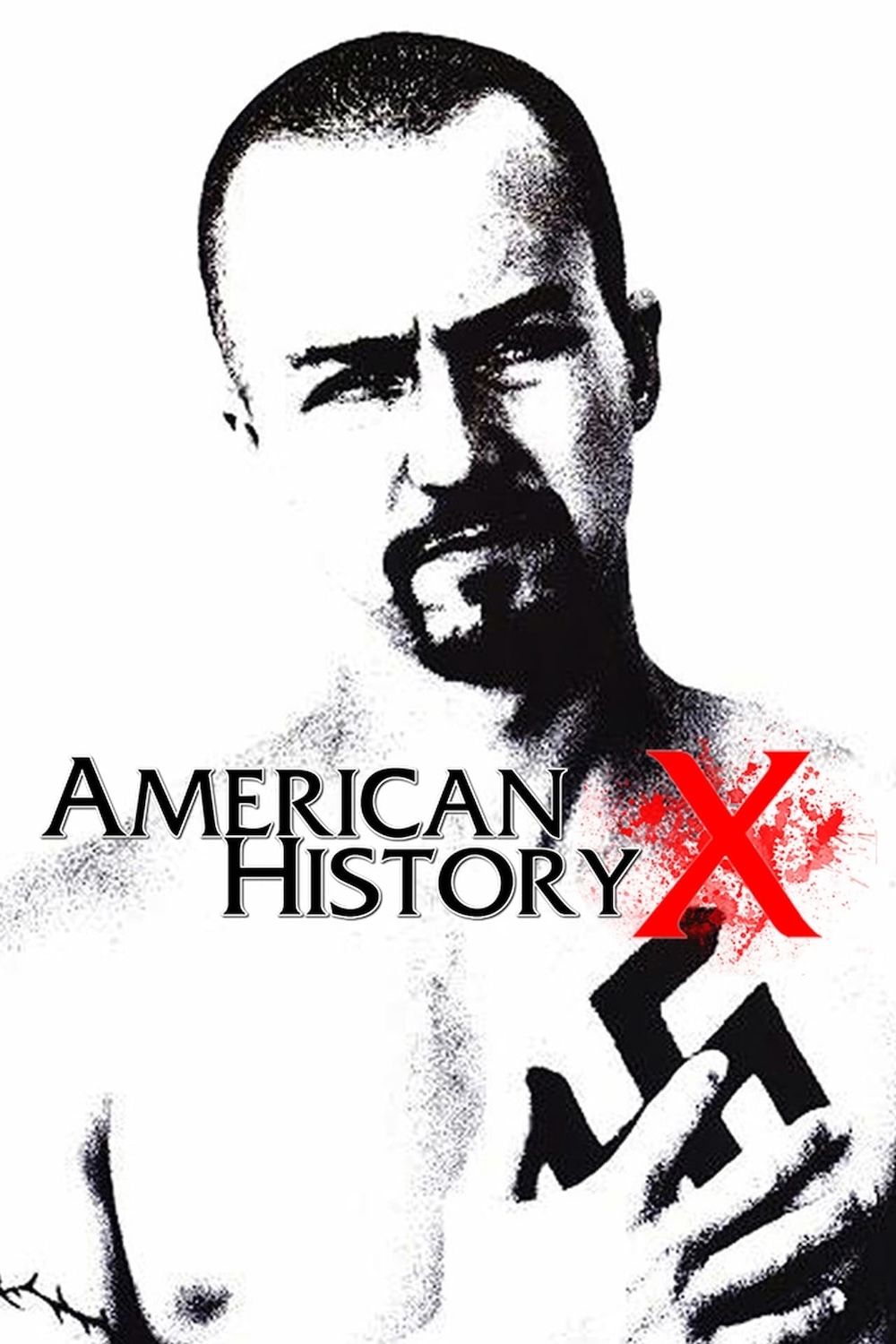

AMERICAN HISTORY X (1998)

A neo-Nazi goes to prison after killing two black youths, and upon his release he vows to change and prevent his brother from following in his footsteps.

A neo-Nazi goes to prison after killing two black youths, and upon his release he vows to change and prevent his brother from following in his footsteps.

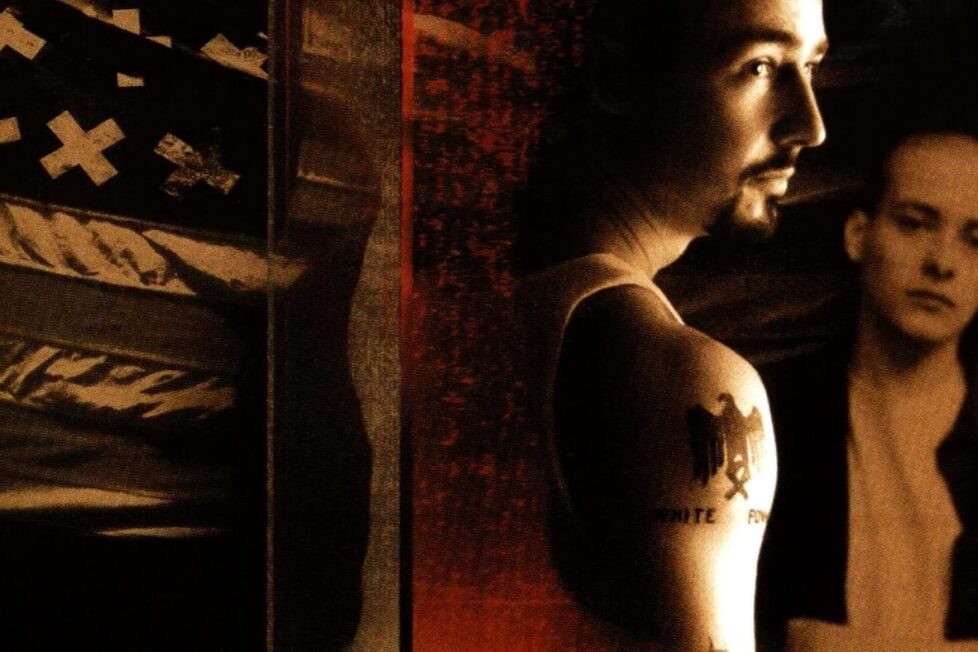

The neon lights of Venice Beach cast an eerie glow as Derek Vinyard (Edward Norton), his sinewy form cloaked in darkness, approaches an unsuspecting triad of burglars. His hand grips a Ruger P94, a menacing presence against the backdrop of the vibrant seaside town. With the stealth of a panther, he moves with feline grace, his eyes locked on his prey, his senses heightened for the kill: he will defend his house.

Derek’s attire reflects his adopted ideology—white boxers, a symbol of purity and innocence, juxtaposed with heavy, steel-toed boots, a reminder of the brutality lurking beneath the surface. His tattoos, a testament to his unwavering beliefs, adorn his skin, a stark declaration of his allegiance.

As he wrenches open the door, Danny Vinyard (Edward Furlong), his younger brother, emerges from the shadows, his eyes wide with horror as he witnesses a crime that’ll forever sear his conscience. The scene unfolds before him, a macabre tableau of violence and betrayal…

Some scenes in cinema resonate with you long after you’ve watched them; American History X has more than a few of those. In Tony Kaye’s directorial debut, there’s a visceral, vehement rage that seeps through the screen. On re-watching this classic, I was struck by how the violence depicted is felt in so many ways. It’s not just the sound of white teeth grinding against dark concrete. It’s not just the image of a towel tightening and choking our protagonist as he’s held down by several inmates. Instead, American History X is a tough watch because of the quiet, calm conversations that inspire people to commit such heinous acts of depravity.

Despite occasional shortcomings of David McKenna’s screenplay, the film shines through with powerful performances, a gripping narrative, and a timeless message that resonates even more urgently today than it did upon its release.

Following the electrifying opening, the narrative shifts to Danny’s school, a shrewd move by director Kaye. While this initial shift might seem like a squandering of narrative momentum, it quickly becomes evident that the hallways of a middle school are just as fertile ground for racial conflict as the darkened streets at night. This juxtaposition serves as a poignant commentary on what children truly learn in school: the insidious poison of hate.

David McKenna, whose script drew heavily from his upbringing, firmly believed that the resentment, prejudice, and hostility that permeate society are not innate, but are instead learned behaviours. By setting the first scene in a school, McKenna offers a compelling and insightful perspective on this notion.

A captivating instructor is essential for an effective lesson, and Derek Vinyard is unquestionably captivating. While advocating for Hitler’s maxims and other white supremacist ideologies, he’s also well-armed with statistics. However, to paraphrase Victorian writer Andrew Lang, Derek uses his questionable figures as a drunk would use a lamp post: for support, rather than illumination. Regardless of accuracy, his assertions are delivered with such conviction that questioning him would seem foolish.

Derek’s unwavering conviction ignites a contagious flame of hostility among his followers. His visceral revulsion and disgust serve as fuel for their animosity, while his self-righteous pronouncements perversely validate their violent actions, imbuing them with a sense of moral justification. The speech Vinyard delivers on the eve of the Asian supermarket attack stands as one of the most chilling moments in the entire film. His demagogic rhetoric, eerily reminiscent of the divisive language employed during Brexit and MAGA rallies, sends shivers down our spines as it strikes uncomfortably close to reality.

Perhaps the scene that best characterises the fractured cultural consciousness of America is the conversation at the dinner table. Doris (Beverly D’Angelo), Derek’s mother, engages in a conversation about the Rodney King case with her new boyfriend, Murray (Elliott Gould). Derek’s polemical nature quickly escalates the discussion into a heated debate, once again wielding his arsenal of statistics. However, Murray isn’t one of Derek’s easily swayed followers, who seek a convenient scapegoat for their sense of powerlessness. Both Murray and Davina (Jennifer Lien), Derek’s sister, raise compelling points, but Derek either prevaricates or dismisses them outright, resorting to ad hominem attacks. This mirrors the increasingly polarized political discourse observed on television, where neither side is willing to yield or acknowledge the validity of opposing viewpoints. Debating has transformed from a pursuit of truth into a zero-sum game, where conceding a point is perceived as defeat.

Mathieu Kassovitz’s La Haine (1995) undeniably influences American History X. Both films chronicle a pivotal 24-hour period in the lives of their protagonists, rendered in gritty, monochromatic cinematography to evoke a palpable sense of social realism. These stylistic parallels extend to thematic resonances, as both films delve into the corrosive power of hatred, exploring its societal impact through the lens of individual experiences. Just as the trio of Parisian delinquents in La Haine serves as a microcosm of French social ills, Derek and Danny Vinyard in American History X provide a searing indictment of America’s enduring struggles with the legacy of slavery and disenfranchisement.

Much like La Haine, American History X leans heavily on its actors to elevate the narrative. In less capable hands, the film would’ve been a self-righteous, moping mess. Fortunately, Norton delivers what is arguably the pinnacle of his illustrious career, embodying the character of Derek with a raw, visceral intensity. He’s utterly captivating. Not only does he physically embody the role of a muscular, virile thug, but he imbues Derek with an unsettling intelligence that adds depth and nuance to the film’s exploration of hate and redemption. Specifically, Derek’s intellect demonstrates that, just because someone is wrong, it doesn’t mean they’re stupid. Derek’s sophistry is what makes him a compelling speaker. His every tirade is mesmerizing and you’re left stunned by the profound depths of human hatred.

In stark contrast to his brother’s brash and domineering demeanour, Danny stands as the antithesis of masculinity, a foil to his elder sibling’s macho persona. Edward Furlong (Terminator 2: Judgment Day) delivers a career-defining performance as Danny, a complex and troubled youth yearning for validation and acceptance. Despite his occasional petulance and outward bravado, Danny harbours a profound inner turmoil, believing he has already grasped the world’s complexities. His brother’s unexpected return triggers a series of epiphanies within Danny, forcing him to confront his emotional vulnerabilities. Among these realizations, none is more jarring than the revelation that the Vinyard family’s enduring heartache stems from a single, fateful conversation at the breakfast table, a poignant reminder of how seemingly innocuous moments can shape the trajectory of our lives.

Stacy Keach’s portrayal of Cameron Alexander, the leader of a large neo-Nazi group in Los Angeles, is a masterclass in understated menace. Though his screen time is limited, he makes an indelible impression with his soft-spoken, eloquent delivery and disarming smile. His words drip with a veneer of sapience, inviting you to understand his twisted worldview. He gently corrects your perceived wrongdoings, positioning himself as the pedagogue and you as the student, eager to learn from his wisdom. To the legions of young, disillusioned men that congregate outside, he’s the father figure they never had, offering guidance and camaraderie.

But beneath this facade lies a chilling reality. With the slightest provocation, the mask slips, revealing the icy gaze of a narcissistic sociopath. His eyes harden, his voice takes on a menacing edge, and the veneer of civility crumbles, exposing the true nature of the man beneath. Keach’s performance is a testament to his versatility, showcasing his ability to convey both charm and menace with equal aplomb.

Dr Bob Sweeney (Avery Brooks) is the Yoda to Alexander’s Emperor Palpatine. In stark contrast to Alexander’s façade, Sweeney’s stern demeanour masks a deep well of empathy, evident in his unwavering commitment to the moral integrity of his community. As the principal of Danny’s high school, Sweeney recognises the insidious influence Alexander wields and takes it upon himself to shield the vulnerable youth from his corrupting grasp. His mission is clear: to prevent Alexander from turning Danny and other impressionable minds down a path of self-destruction. Sweeney’s unwavering resolve sets him up for a relentless battle, where he must fight for the soul of every adolescent teetering on the brink.

Sweeney’s initially soothing demeanour gradually transforms into a somewhat pontifical tone as the film progresses. His delivery of life lessons to Derek becomes increasingly didactic, suggesting that he’s evolved into a mere mouthpiece for the film’s moral compass. However, not all of his preachings are excessive. During his prison visit, he poses a simple yet profound question to Derek: “Has anything you’ve done made your life better?” This seemingly straightforward query shatters the illusion of purpose that Derek has clung to.

While the performances are generally commendable, there are instances where they lose their authenticity. Some dialogues come across as forced, perhaps because people don’t typically converse in clichés—unless, of course, it’s a sententious Hollywood movie. While some of this moralizing can be unrestrained at times, given the film’s crucial message, there’s a case to be made that a direct approach is preferable to subtlety that falls flat.

The script’s uneven quality, which manifests in a few underwhelming interactions, could be attributed to the ongoing revisions made by Norton and Furlong. Without a clear understanding of the specific changes they introduced, it would be unjust to blame them for these shortcomings solely. However, this constant state of flux could explain the script’s occasional lack of polish and the inconsistent delivery of certain lines. While I wouldn’t characterize any moment in the film as a nadir, a few interactions do fall short of believability.

Tony Kaye has been quite vocal about his dissatisfaction with the final product, attributing many of its shortcomings to Norton’s interference. His frustration over the loss of creative control reached a boiling point during the editing process, culminating in a heated argument that resulted in Kaye punching a wall and requiring stitches. This incident, coupled with his subsequent decision to spend $100,000 of his own money on advertisements criticizing New Line Cinema and Norton, has become legendary in Hollywood circles. In a rather unusual move, Kaye even brought a priest, a rabbi, and a Buddhist monk to a meeting with the film’s producers. While it might sound like the setup to a joke, this anecdote highlights the depth of Kaye’s resentment. Despite his public disavowal of the film, Kaye has acknowledged that his own ego played a significant role in the conflict and practically destroyed his career.

Considering the reported behind-the-scenes conflicts, it’s difficult to form a definitive opinion on the film’s ending. While undeniably impactful, it also verges on the melodramatic. The excessive use of slow-motion close-ups of Norton’s face feels self-indulgent and undermines the intended shock value of the climactic scene. For those who have seen the film before, the dramatic finale may lose some of its impact due to familiarity.

Moreover, the film’s ending is somewhat ambiguous regarding its contribution to the overall message. While interpretations such as a depiction of violence’s cyclical nature or the impossibility of escaping one’s past are plausible, they strike a rather pessimistic tone that doesn’t entirely harmonize with the film’s themes of redemption and personal accountability. If anything, the ending could be perceived as suggesting that societal issues are so deeply ingrained that they can never be ameliorated or fully rectified.

Irrespective of the interpretation one chooses to ascribe to its ending, American History X remains a profoundly moving cinematic experience. It stands as a compelling testament to the futility of hate, vividly portraying how insidious networks can be constructed to exploit the powerful emotions of misguided and vulnerable individuals. The film suggests we should show compassion to all, regardless of the rancorous bile they spew; they’re not evil inside—they’ve simply lost their way.

American History X delves into the didactic nature of hatred, exposing how its roots often lie within the confines of the nuclear family. The film’s enduring power stems not only from its shocking violence but also from its unflinching portrayal of systematic manipulation and casual, everyday indoctrination. It’s watching an old man prey on a young boy’s mind, defiling it right before our very eyes. It’s witnessing the death of a boy’s future as his idealism is desecrated by his father’s bigotry. And it’s seeing an impressionable child yield to the powerful force of hate.

The film serves as a stark reminder of how anger can spiral out of control, gaining momentum like an unstoppable avalanche that grows larger and more destructive with each passing moment, until it reaches a point where its origins and end are obscured from view. In the face of such overwhelming adversity, we often seek simple solutions, assigning blame to society, God, or those around us. However, as Sweeney demonstrates, true progress hinges on asking the right questions. Particularly, amidst all the chaos in the world, what actions have you taken to make your life better?”

USA | 1998 | 119 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Tony Kaye

writer: David McKenna

starring: Edward Norton, Edward Furlong, Fairuza Balk, Stacy Keach, Elliott Gould, Avery Brooks & Beverly D’Angelo.