Take 5: Alternative Christmas Movies

Are you looking for some Christmas movies to watch this month? Tired of the usual titles and repeated classics? Five of our writers have chosen some Alternative Christmas Movies, which are either not commonly remembered as taking place over the festive season, receive less airplay on television these days, are totally overlooked curios, or perhaps failures in need of some reassessment decades later.

There’s probably something here to tempt you into a viewing. But if not, leave your own suggestions in the comments below.

Stanley Kubrick’s last film was as much a fitting send-off to the century that birthed cinema as it was to his career. It feels utterly perfect that it’s set during the last month of 1999. Striking a mercurial yet cosy tone and often lit with strings of glowing fairly lights, Eyes Wide Shut evokes an otherworldly holiday malaise that is familiar despite its dreaminess.

The director was satisfyingly mysterious right until the end, offering up an impressionistic view of a crumbling marriage that already feels like a distant memory. At a time of year when time seems so pertinent, when we find ourselves looking back at the year that has been (and anxious about the one ahead), it can be essential to delve into cinema that represents the strangeness of navigating your deepest thoughts while the world around you celebrates. Eyes Wide Shut is such a film; a personal, hypnagogic dream of the winter months of a relationship. It may have been Kubrick’s last gift to the world, but what a gift it was.

Are you one of the people who get annoyed when everyone is getting ready for Christmastime in October? Pottersville is hardly what most people would call a ‘Halloween’ or ‘Christmas’ movie, but it is about a small town obsessed with a monster right before the holidays. I say hardly because pretty much nobody is calling this movie anything because it flew so far under the radar most people’s initial reactions are disbelief at the star-studded cast.

Maynard (Michael Shannon) attempts to surprise his wife (Christina Hendricks) only to find her with the Sheriff (Ron Perlman), enjoying each other dressed as furries. Maynard gets incredibly drunk and storms through the night in a cheap gorilla costume, making witnesses believe they caught a glimpse of Bigfoot. With the town struggling, Maynard just wants to keep people happy this Christmas but the host of a monster-hunting show and his big game hunter friend closing in on the illusive beast puts him at risk in ruining everything.

The final product is probably not as exciting as you’re imagining but Pottersville is a light-hearted and well-meaning venture, somehow sprung out of nowhere, as Daniel Mayer and Seth Henriksen have ever only written and directed this one movie. The most shocking is you might assume this was shelved for years… but no! It was made in 2016 while Shannon was acting in Midnight Special (2016), Loving (2016), and Nocturnal Animals (2016), released a month before The Shape of Water (2017)! If the guy getting Academy Award-nominated for ‘Best Supporting Actor’ that year wanted to do a weird little ‘Christmas Bigfoot’ movie, then surely it’s worth checking out!

Set in the Swedish town of Uppsala, 1907, Ingmar Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander (originally intended to be his final autobiographical opus) follows the Ekdahl family’s two siblings: the imaginative Alexander (Bertil Guve) and his sister, Fanny (Pernilla Alwin). Their journey begins, of course, at Christmastime, where a short Nativity play is held in a theatre the siblings’ parents, Oscar (Allan Edwall) and Emilie (Ewa Fröling), both own. Days later, however, Oscar dies from a stroke, leading a devastated Emilie to marry the strict, commanding bishop Edvard Vergérus (Jan Malmsjö). Gradually, Alexander, Fanny, and Emilie are forced to confront Edvard’s abuse, with Alexander specifically resorting to his talented imagination and storytelling.

While Fanny and Alexander plainly sets its opening sequence during Christmas, the film’s mystical tone holds the answers to why it functions so well as a holiday film (or miniseries, depending on which version you watch) on a deeper level. For instance, Alexander’s tales often invoke a variety of ghosts, such as his own father or Vergérus’s deceased family, harkening back to numerous classic Dickensian holiday parables. Another example of this is the mysteriously prescient Jacobi family, who help Alexander make sense of and realize his narratives. It’s through this that the film establishes a fairy tale-esque air, compounded with themes of religion, agency, and the power of imagination.

It’s no coincidence that Bergman chooses to feature Christmas so explicitly in Fanny and Alexander; for a film so interested in the spiritual power of stories and parables, its atmosphere is inevitably magical, perhaps even divine. The film is as much a Christmas story as the Nativity scene that spawned the holiday; it knows that every story can be an act of God, a narrative where various lives intersect, in all their complexity, to create something wonderful.

This straightforward telling of Charles Dickens’ most-filmed work is often considered the best, but it’s the marvellous performance of Alastair Sim in the title role that sticks in most memories. Equal credit must go to director Brian Desmond Hurst for some hugely atmospheric sequences and to screenwriter Noel Langley (one of the Wizard of Oz writers) for so deftly blending comedy, terror, pathos, and redemption.

It gets straight to the point from the first minutes (Scrooge refusing to give to charity, Scrooge shooing away carol-singing kids) and plunges us into a black-and-white Dickensian world much more comforting than, say, David Lean’s Great Expectations (1946) or Oliver Twist (1948). (A later colourised version also exists, but works less well.) Though Scrooge is nasty, he’s amusingly and unthreateningly nasty.

Things change, though, when the hauntings begin; first from the spirit of Jacob Marley and then from the three Ghosts of Christmas. There’s genuine uneasiness here, and the expressionist presentation of Scrooge’s home is a nightmarish contrast to the jolly Christmas streets. Eventually, of course, it all ends happily and there’s a hilarious sequence where Scrooge embraces seasonal generosity with such zeal his housekeeper fears he’s gone mad.

Sim is terrific, as is Mervyn Johns as a slightly camp Bob Cratchit, and there’s a nice Richard Addinsell score—most notable for a lovely arrangement of “Barbara Allen”. If Scrooge has one flaw it’s that it spends too long on the Ghost of Christmas Past, when we really want to get to the gloom and misery of the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come. But the lengthy flashbacks are necessary to show that Scrooge isn’t inherently evil (just “changed by the harshness of the world”) and to set things up for an ending which is feel-good without diving too deeply into schmaltz. The perfect antidote to more contrived, or cynical, Christmas films.

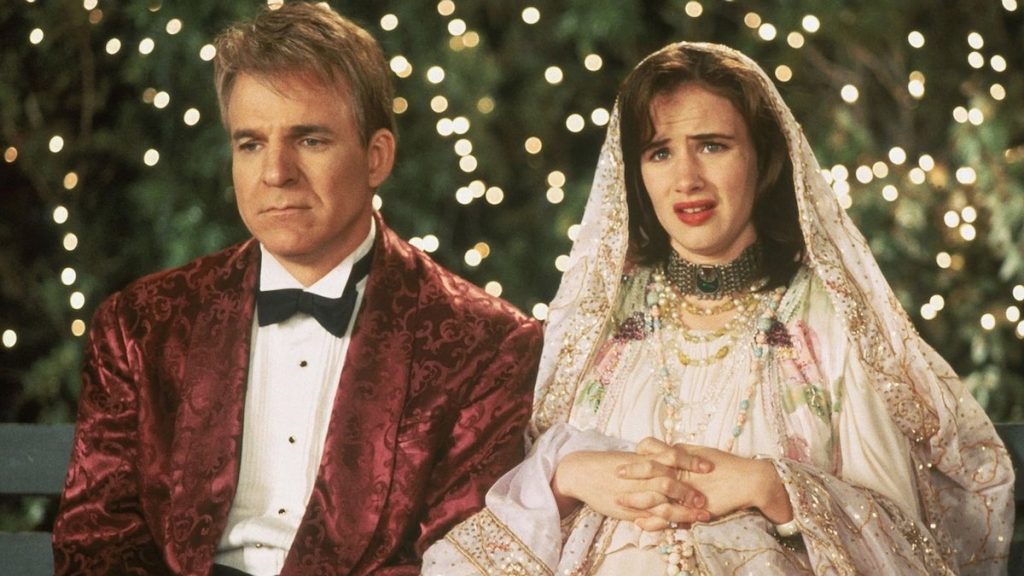

Some Christmas movies are rightful classics, but are some never received the love they deserved. Mixed Nuts isn’t your traditional, heart-warming festive film to watch curled up by the open fire. Based on the French film Le Pere Noel Est Odure Ordure / Santa Claus is a Stinker, it’s a dark comedy revolving around the final chaotic hours of Christmas Eve.

Unlike Nora Ephron’s sentimental Sleepless in Seattle (1993), Mixed Nuts has no interest in pandering to its audience. Phillip (Steve Martin) manages a suicidal helpline called ‘Life Savers’, assisted by Catherine (Rita Wilson) and Mrs Munchnik (Madeline Kahn). When they receive an eviction notice on Christmas Eve, they’re in desperate need of a miracle to save their business. The ensemble of eccentric characters provide hilarious moments. Martin’s (Roxanne) comic timing is perfect and watching the character crumble under the pressure of Christmas is surprisingly relatable.

The dark humour won’t appeal to everyone, which explains why it was a box office flop. However, the mix of satire and OTT absurdity of everything that happens on Christmas Eve works—surprisingly. The title comes from an anecdote Philip tells early about his dad, who once said “in every pothole, there is hope”, just before being run over by a truck carrying mixed nuts. The selfish characters, dry humour, and observational dialogue about human inanities evoke Seinfield (1989-1998) and Curb Your Enthusiasm. At one point, Philip’s dumped by his girlfriend, who says “I would’ve preferred to of faxed you then tell you on the phone. It would have been more meaningful.”

At its core, Mixed Nuts is about outsiders with no home to call their own, who come together for the festive period. In Philip’s final message he says “Christmas is a time when you look at your life through a magnifying glass, and whatever you don’t have feels overwhelming. Being alone is so much lonelier at Christmas. Everything sad is so much sadder…” Mixed Nuts embraces that Christmas is possibly the most stressful and frustrating time of year, but there’s still joy coming together with those in solidarity.