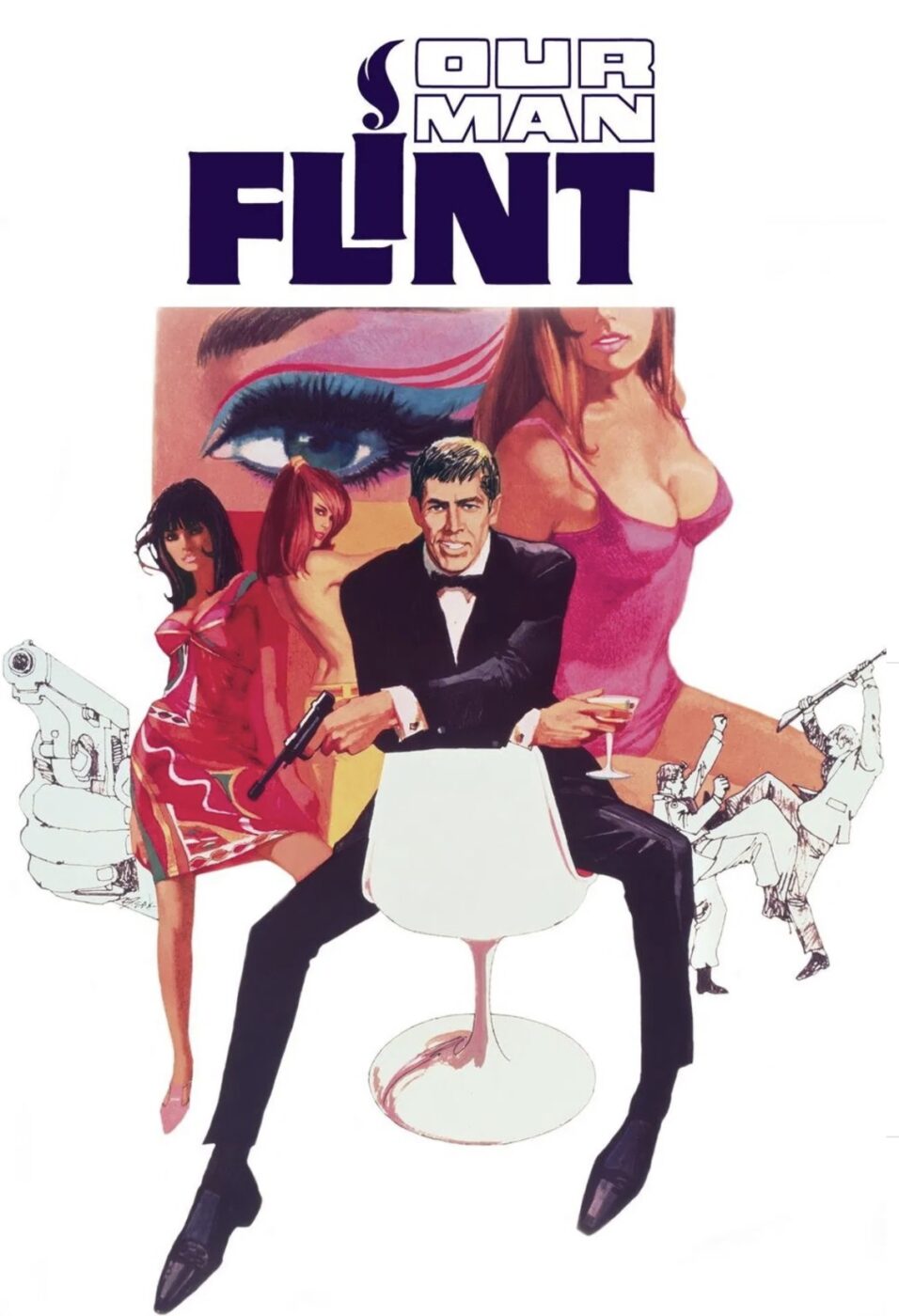

OUR MAN FLINT (1966)

When scientists use eco-terrorism to impose their will on the world by affecting extremes in the weather, Intelligence Chief Cramden calls in top agent Derek Flint.

When scientists use eco-terrorism to impose their will on the world by affecting extremes in the weather, Intelligence Chief Cramden calls in top agent Derek Flint.

Cultural trends that are so much ‘of their time’ often fall from favour, only to enjoy a renaissance when the nostalgia of an older generation overlaps with the ironic retro appeal for a younger one. 60 years after its release, Our Man Flint may now claim such status, particularly as retro-futurism has recently resurfaced in mainstream cinema—most prominently in the excellent production design showcased in The Fantastic Four: First Steps (2025). Of course, in the mid-1960s, the retro-futurism of Our Man Flint was simply futuristic. Today, the opening gambit also carries a renewed sense of urgency as we witness one disaster after another: earthquakes, avalanches, volcanic eruptions, tidal waves, devastating storms, breached dams, and villages swept away by the ensuing torrents.

These are not the natural disasters they may appear to be, but rather the work of Galaxy. No, this isn’t chocolate-related product placement, but a secret cabal that has mastered climate control. By raising global temperatures by five degrees, they are using the chaos as leverage to dominate the world’s nations. And, just like the villains of today, they are creating this climate catastrophe by drilling deep into the Earth. Galaxy’s initial demands are that every government dissolve its military, cease the use of nuclear energy, and dismantle all nuclear weapons. This doesn’t sound too evil until we later learn they intend to usher in a peaceful, drug-controlled utopia where all men are ‘work units’ and women are conditioned to become compliant ‘pleasure units’—a simplified take on Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and an oblique critique of contemporary society.

In an emergency summit of the Zonal Organisation [of] World Intelligence [and] Espionage, or Z.O.W.I.E., world leaders are frantically considering their options in what seems to be a no-win situation. Having already lost several special forces teams and top agents, they vote to commission one more operative in a last-ditch effort to infiltrate and bring down the masterminds behind Galaxy.

As Britain’s top secret agent—no, not ‘Double-O-Seven’ but ‘Triple-O-Eight’ (Robert Gunner)—is currently indisposed on an international narcotics mission, the nations argue about who else could be worthy of the challenge. Finally, it’s agreed to let the super-computer decide. Here, we’re treated to some of that lovely retro-futurism: a hall of computer cabinets, spinning spools, blinking lights, and the clacking of punch cards. Cramden (Lee J. Cobb) feeds in all the qualities and characteristics necessary to succeed and, after much deliberation, the computer spits out a name: Derek Flint (James Coburn).

Some of those chunky computer consoles were genuine state-of-the-art machines, including at least one Burroughs B220 console, a favourite prop of sci-fi set designers in the sixties. It even featured in the 20th Century Fox Batman (1966–68) television series starring Adam West, which began its three-year run the same year and shares similar camp sensibilities. The humour of Our Man Flint also relies on the exaggeration of established genre tropes, but it has a second layer of clever jokes that may take a while to sink in. For example, Flint’s favourite gadget is a gold lighter with 82 functions—or 83, if used to light a cigar. There’s one joke thrown away so blatantly that we may miss the secondary prop gag: think a little harder and one realises the gadget incorporates what is among the first ‘gadgets’ used by humans—a piece of flint, of course!

Derek Flint was created by writer Hal Fimberg, with significant guidance from producer Saul David, who insisted that the ridiculously cool secret agent have a personal moral code that naturally aligned him with the side of good, rather than sworn institutional loyalty. He wasn’t so much a pastiche of James Bond as a counter-argument to him.

By the mid-1960s, James Bond movies were cultural events that spilled out across any medium that could carry the brand—merchandise tie-ins from toys to top-quality timepieces, television spots, magazines, and cereal packs. For my family, they meant a trip to the cinema, which was a special treat. For the earlier movies, I was too small to have my own seat and would sit on a parent’s lap, sometimes loudly misinterpreting scenes to the amusement or chagrin of those in nearby rows. The first Bond movie I saw was probably an early re-release of the fourth, Thunderball (1965), which confirmed the global supremacy of the franchise and sparked so-called ‘Bondmania’.

Flint was an all-American hero for a new age—individualistic and anti-bureaucratic, with a counter-culture hipster ethos despite being materialistic and super-rich. He’s a modern man without being fully ‘reconstructed’, reinforcing the established patriarchal social structures of the day while challenging other perceived norms, such as the nuclear family. So, while there is plenty of overlap, there’s also a marked contrast to the authority-loyal, royalty-respecting ‘best of British’ Bond.

Flint is a hero in the tradition of Sherlock Holmes—cerebral, encyclopaedically knowledgeable, yet also a man of action. Holmes, after all, was a champion fencer, crack shot, and formidable boxer. When an assassin fails to kill Flint with a poison dart fired from a harp string, it’s a visual gag referencing ‘the harp edit’ cliché, where a glissando heralds a transition or flashback. Through a process of deduction that Holmes would’ve been proud of, Flint notes that the forensic analysis of the dart includes traces of garlic, saffron, and fennel. These are key ingredients of Bouillabaisse, a Provençal fish stew originating in Marseille, where each chef’s ratio of ingredients acts like a culinary fingerprint. It’s the first in a trail of clues that leads him through the smoky dives of France, the sunny streets of Rome, and finally to a secret base on a remote island.

Flint also owes something to Doc Savage, the original superhero polymath who began in 1930s pulp novels and later transitioned into comics, gaining mystical abilities after training in Tibet. This lineage predates Doctor Strange’s connection to the mystic arts and long precedes The Dark Knight’s Tibetan training.

Apparently, it was James Coburn who pushed for Flint’s interests to include Eastern mysticism, Tibetan meditation techniques, and martial arts as a way of promoting interest in these ‘new age’ concepts. Almost by accident, this aligned the character with the emergent popular counter-culture, making him a man in step with his times.

Broader interest in Tibet followed the annexation of the nation by China in 1959, when the Dalai Lama was forced to flee to India. The emergent hippy counter-culture seized on the alternative spirituality offered by Tibetan Buddhism and other Asian philosophies. The Beatles were soon to hitch themselves to this bandwagon, famously travelling to India in 1968 for a spiritual retreat to create their White Album. So, in 1966, Flint was at the cross-cultural vanguard.

My favourite moment in the movie comes when Flint finally agrees to the mission. We cut to a scene of him lying between two chairs—head on one, feet on the other—-his back straight as a board. Even the mise-en-scène is packed with detail. The fact that his chess set was red and white instead of black and white was simply cool; I’m sure the eight-year-old me missed the symbolic relevance of white versus ‘the Reds’—the Cold War communist threat.

“It worries me so when he stops his heart this way…” says Leslie (Shelby Grant). To which Anna (Sigrid Valdis) replies, “Yes, but it does relax him.” At a set time, his wristwatch stimulates his pulse to restart and he awakes. Refreshed and ready to save the world, he bids a somewhat tender farewell to his four sophisticated female assistants: Leslie, Anna, Gina (Gianna Serra), and Sakito (Helen Funai). Naturally, the villains try to control Flint by abducting the women he cares for, which only makes him more determined.

James Coburn’s breakthrough came as the knife-throwing tough guy Britt in The Magnificent Seven (1960), yet he was still transitioning from television supporting roles when he landed Flint. It was his first starring role and the one he became synonymous with. By 1968, he was ranked the twelfth biggest star in Hollywood by The Washington Post.

Although his karate and kung fu are stylised, Coburn was a serious student of martial arts and a friend of Bruce Lee; he was even a pallbearer at Lee’s funeral. Hong Kong was also capitalising on Bondmania with super-spy pastiches just as wild as Our Man Flint—Wei Lo’s The Golden Buddha (1966) being a notable example. In France, André Hunebelle was rebooting the Fantômas IP with an action-comedy trilogy that owed just as much to Bond.

Coburn is the perfect Flint. His rugged good looks are balanced by a carefree swagger and a lackadaisical demeanour that questions traditional masculinity. Flint does martial arts but also teaches ballet, has refined aesthetic sensibilities, and enjoys being pampered. Despite his ‘harem’ of female staff, Flint’s ‘appreciative sexism’ stands in deliberate opposition to Bond’s misogyny. While Bond’s women are often treated as disposable narrative adornments, one feels that Flint’s team could’ve starred in their own spin-off—Derek’s Angels, perhaps? Charlie’s Angels (1976–1981) would air a decade later.

With the rise of the Women’s Liberation Movement, patriarchal societies were being forced to examine ingrained discrimination. Traditionally, men were ‘entrapped’ by their jobs to maintain a home and a wife; it was often seen as a failure of masculinity if a wife had to work.

When Flint finds Galaxy’s secret base—-with its docile, drugged male workforce and conditioned female ‘pleasure units’—it serves as a snapshot of the era’s gender politics. In that context, the literal liberation of the women in Our Man Flint was a bold move for the spy genre. Even the villainess, Gila (Gila Golan), gets a shot at redemption.

In the end, it still takes a hyper-competent male hero to restore order. Nevertheless, Flint’s idealised masculinity and tongue-in-cheek style have stood the test of time better than Bond’s thinly veiled sociopathy. Our Man Flint remains relevant because it embodies its era so completely: the optimism, the mysticism, the paranoia, and the downright silliness. It is a time capsule of a culture in transition, caught between the fading certainties of the post-war world and the impending shock of the new.

The film was a hit and immediately pervaded popular culture. Even Hanna-Barbera exploited its popularity with the animated spoof A Man Called Flintstone (1966). A sequel, In Like Flint (1967), was rushed through, though it occasionally used satire as an excuse to parade the very sexism it intended to lampoon.

In 1972, plans for a third film titled Flintlock ended up as an abortive TV pilot penned by Harlan Ellison. Eventually, the script was jettisoned and a television movie, Our Man Flint: Dead on Target (1976), materialised with Ray Danton. There were hopes for a full series, but without Coburn, Flint simply lost his spark.

USA | 1966 | 108 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH FRENCH ITALIAN

director: Daniel Mann.

writers: Hal Fimberg & Ben Starr (story by Hal Fimberg).

starring: James Coburn, Lee J. Cobb, Gila Golan, Edward Mulhare, Benson Fong, Shelby Grant & Sigrid Valdis.