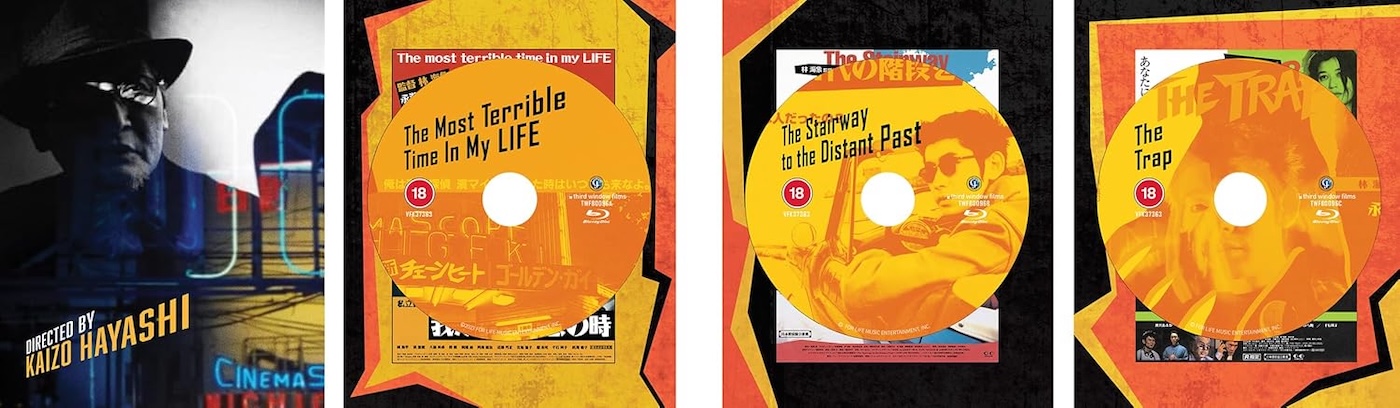

Kaizo Hayashi’s Maiku Hama Trilogy (1994–1996)

A trilogy of films about Yokohama private eye Maiku Hama, directed by Kaizo Hayashi.

A trilogy of films about Yokohama private eye Maiku Hama, directed by Kaizo Hayashi.

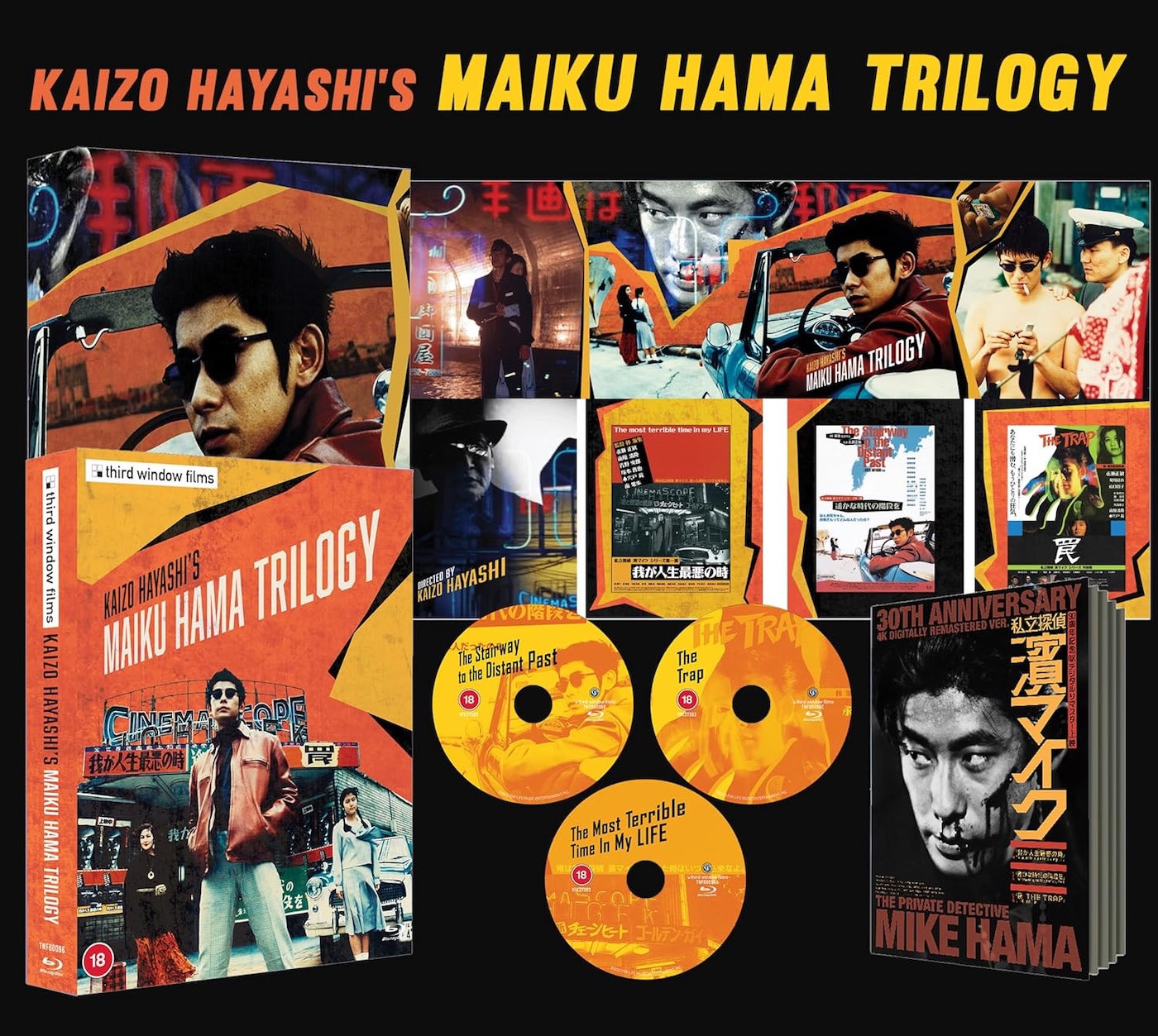

Kaizō Hayashi is yet to gain the wider recognition he deserves as one of Japan’s most innovative and influential auteurs. His beautiful ode to the cinema of Japan, To Sleep So as to Dream (1986) was a revelation for me as one of the most surprising films I’ve seen in recent years. So, I was eager to find out if this new Blu-ray box set from Third Window Films of his seminal ‘Maiku Hama Trilogy’, lovingly restored and remastered at 4K, would live up to my high expectations. The short answer: yes.

Hayashi sits comfortably in a lineage of great directors who exploit and celebrate the language of cinema itself such as Carl Theodor Dreyer, Andrei Tarkovsky, David Lynch, Quentin Tarantino… some would call it ‘pure cinema’, but I like the term coined by Sergio Leone—‘cinema-cinema’.

Although each film is self-contained to some extent, the central narrative develops across all three, and they are best appreciated as acts in one big story. So, it makes sense that Third Window Films are releasing them together as a box set.

The genre-blending trilogy becomes increasingly experimental, with several tonal shifts as it gradually morphs from noir, through brutal yakuza power play, family drama, political thriller, Japanese akai, and intense psychological horror, before disintegrating into surreal existential angst… with plenty of fun and visceral thrills along the way. Although they may be too clever for their own good at times, they pile on the intrigue and never fail to entertain. Essential viewing for anyone with an interest in the cinema of Japan and connoisseurs of noir.

Maiku Hama is a private detective working in Yokohama. Agreeing to aid a Taiwanese waiter named Yang who is in search of his missing brother, Hama soon becomes embroiled in a gang war and a revenge plot between the two brothers.

As with all three films, the first shot is of the Nichigeki cinema hoarding that advertises both Western and Japanese films, quite literally sign-posting the collision of cinematic styles that will be reflected in the super-cool pop iconography to follow. Ironically, the film showing this time is The Best Years of Our Lives (1946), a hugely successful film about three US servicemen trying to reintegrate into civilian life while dealing with the physical and mental traumas of war. Like many films made in post-war Japan, an important subtext of The Most Terrible Time in My Life addresses the social, cultural and literal fallout of the Second World War, and although its setting is contemporary with its production, it still feels timeless.

The opening of each film also follows the same structure as a client arrives in the cinema foyer where receptionist Asa (Noriko Sengoku) insists they buy a ticket before allowing them to pass and ascend the stairs to a private booth next to the projectionist’s where Maiku Hama (Masatoshi Nagase) has his modest office. After their brief exchange, Maiku sets out in his snazzy Austin Nash Metropolitan Convertible. The distinctive flying lady hood-ornament places it as a 1955–58 model, which were made in the UK to appeal to the US market as a compact yet stylish urban runaround. This is another overt reference to the post-war assimilation of Western influences into the culture of Japan.

Masatoshi Nagase is a versatile leading man who is generally cited as being best known for his early lead role in Mystery Train (1989), the cult film directed by Jim Jarmusch. But I recognised him from Takashi Ishii’s Original Sin (1992), made immediately before this first appearance as Maiku Hama, and more recently in Gakuryū Ishii’s excellent existential The Box Man (2024).

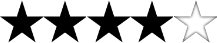

Beautifully shot in black and white by cinematographer Yûichi Nagata, The Most Terrible Time in My Life starts out light-hearted. The fourth wall is ruptured twice within the first five minutes, including our protagonist, Maiku Hama, addressing the camera to assure us it’s his real name. Yet he seems too young and good-looking to be Japan’s answer to Mickey Spillane’s hard-boiled P.I. that his name might suggest. He also tells us that he’s working to earn enough to send his younger sister Akane (Mika Ohmine) to college. He seems to be such a nice guy, but we soon learn he has a chequered past and is still hounded by the unscrupulous Lt. Nakayama (Akaji Maro). It may feel like a spoof of the hard-boiled detective genre, but such expectations are soon shattered by a level of violence that situates it within the jitsuroku eiga genre of brutal yakuza films.

When a young Taiwanese waiter is ridiculed and bullied by a local hoodlum, Maiku intervenes and in the altercation that follows loses a finger. After his friends retrieve the severed digit from the dog that tried to make off with it, it’s reattached so Maiku will spend most of the film with his hand splinted and bandaged. It’s a variation on a theme, reminiscent of Jack Nicholson’s bandaged nose in Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974) and is the first of several injuries that Maiku will accrue. Turns out he’s tougher than he looks. The waiter Yang (Hai-Ping Yang) feels responsible for Maiku’s injury and tries to pay him some compensation which he refuses. So, by way of payback, he hires him to find his older brother.

As this fine box set brings the Maiku Hama trilogy to a broader audience outside of Japan, I won’t discuss too many plot details. It transpires that the Yang brothers came to Japan to escape extreme poverty, hoping to take advantage of the post-war boom economy, but fell in with a Yokohama gang of Chinese immigrants. However, the older Yang brother has disappeared. It seems he fell in love with a prostitute but couldn’t afford to buy her freedom, so they eloped and he joined another gang for protection. Trouble is brewing between the Taiwanese, Hong Kong, and Korean gangs while the yakuza bide their time and let the in-fighting destabilise their rivals. Both brothers are renowned hitmen and inevitably, one is hired to kill the other while Maiku tries his best to save them both.

The narrative remains gripping even as it gradually evolves from quirky noir pastiche into an exploration of some serious themes such as the various prejudices between different Asian ethnicities, the dangers of over-romanticising the past, the search for cultural and personal identities… The villains are also shown to be real people, some with very human feelings and noble motivations, at least within the context of their desperate lives. Of course, there are some that are genuinely nasty—we’re introduced to scar-faced gang boss Masaru Kanno (Shirō Sano) and his sadistic finger-chewing henchman, Yamaguchi (Shinya Tsukamoto). Also, Hoshino (Kiyotaka Nanbara), a wide-boy cabby who becomes Maiku’s reliable sidekick.

Throughout, the framing and compositions are a consistently inventive mix of dramatic angles and a variety of dynamic shots from close-ups to crane shots. The influence of manga and other narrative image formats can be detected. Toward the finale there’s a sudden, visually shocking use of red to emphasise a moment of visceral violence that reminded me very much of Frank Miller’s minimal but well-placed use of spot colour in his series of Sin City graphic novels. This sudden flash of colour presages the tints that creep in as the end credits approach, to be followed by a full-colour post-credit teaser for the next instalment…

JAPAN | 1994 | 92 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE & COLOUR | JAPANESE / TAIWANESE / MANDARIN

Hama has been reduced to combing the mean streets of the Yokohama waterfront on a borrowed bicycle…

Beautifully shot in saturated colour, again by cinematographer Yûichi Nagata, part two also starts out light-hearted. We have the same sequence of events, this time with Asa making the pertinent observation that “movies do well in bad times.” His first client wants him to find their missing dog, and as Maiku sets out in his Metropolitan Convertible he again introduces himself directly to camera. Then he almost rear-ends a tow truck that’s blocking the road, evidently waiting to repossess his beloved car, thoughtfully leaving him a bicycle to continue his work. Despite being shot in colour and with a comedic opening gambit, it soon becomes even more broodingly atmospheric with strong contrasts between coloured lighting and deep smoky shadows that reassert the noir aesthetic.

By now, Masaru Kanno is not simply a gangland crime lord but has moved into the political arena, campaigning to become a councillor for the Yokohama riverfront area. Offering the keys to his impounded car as payment, Lt. Nakayama bullies Maiku into helping him trace the route stolen goods take along the river which doesn’t fall under the jurisdiction of the metropolitan police nor that of the harbour police. It seems that since the US occupation ended way back in 1952, the riverfront has remained under the control of the enigmatic and ruthless ‘White Man’ (Eiji Okada) who supposedly died in the war… this reflects Japan’s loss of identity and control while governed by the US after the defeat of the Imperial regime. Regaining sovereignty as a democratic nation was followed by a period of introspection, a reassessment of traditional cultural iconography along with assimilation of foreign influences while searching for a new national identity.

There’s a period around the mid-point of the film when mood seems to replace narrative and there’s a lull in what had become satisfyingly rhythmic pacing that took its cues from the lively jazz score by Meyna Co—a collective featuring Yōko Kumagai and Hidehiko Urayama, two composers whose first score had been for Kaizō Hayashi’s directorial debut, To Sleep So as to Dream.

Maiku discovers that the stolen furs he’d been tracking for Nayayama are just a front for gun smuggling. The revelation triggers a spate of brutal executions that Maiku feels responsible for. Also, an exotic dancer known as Dynamite Sexy Lily (Haruko Wanibuchi) convinces Maiku that she’s his and Akane’s mother, hinting that his real father and the White Man are one and the same. This additional layer of family drama touches upon themes of generational legacies—that the world we live in is created by the previous generation and we have no choice but to deal with the repercussions.

The third act takes us somewhere completely unexpected as Maiku decides to confront the man who may be his father and may also be a ghost. Suddenly the film veers into the realm of portal fantasy as Maiku enters another world of disjointed reality, frozen tableaux of the past, and a final confrontation in a surreal industrial wasteland of abandoned factories. In some way this echoes the dissolution of substantial reality to be replaced by the immaterial world of cinema, conjured from light and shadow. There’s also a parallel with the river journey in Apocalypse Now (1979) that takes us into the deranged world of Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando).

JAPAN | 1995 | 102 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

When a hooded stranger appears in Hama’s office with the cryptic challenge “I want you to look for me,” Hama is drawn into a string of bizarre serial murders that have Yokohama’s police baffled and the city terrified…

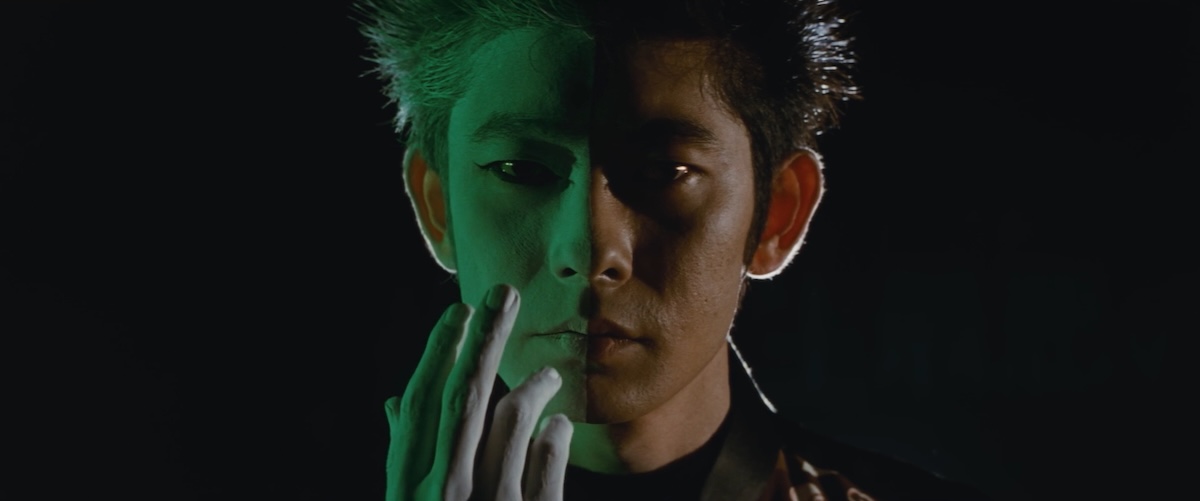

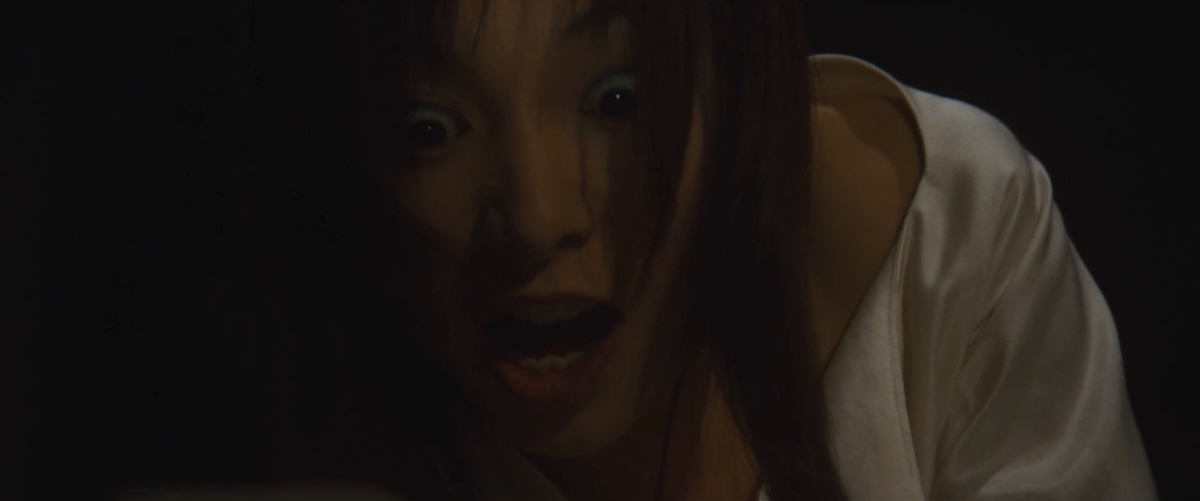

The dark intensity of the final act of Stairway to the Distant Past sets the tone for the starting point of the third instalment. This time, a mysterious masked client slips through the cinema foyer, unnoticed by the usually vigilant Asa. Appearing in Maiku’s office, the figure removes the mask to reveal a severely disfigured face before slipping a photograph across the desk with the instruction to “find me.” The tone darkens further, and there’s a genre shift into psychological horror as Maiku’s grip on reality and his own identity begins to slip.

While investigating a series of murders of young, beautiful women who turn up dead in public places, each wearing a similar hat and summer dress and wearing the same rare scent—a perfume that Akane coincidentally purchased on Maiku’s behalf for him to gift to his new girlfriend, Yuriko Yoshida (Yui Natsukawa), a mute who volunteers at a local church and works with deaf children. The metaphor of struggling to find a voice while others don’t hear you has multiple meanings here relating to both personal and cultural identity.

Of course, she’s targeted by the serial killer who drugs women with similar appearances and forces them to comfort a young man, Mikki (Masatoshi Nagase is excellent in a dual role) who we’re told is afflicted with severe brain damage. The suspense builds as the fractured narrative becomes increasingly weird and worrying. Identity and memory are central throughout the trilogy, but The Trap intensifies these themes. Maiku is framed as the serial killer and now has to keep his sister safe, save Yuriko, uncover the killer’s identity, and peer into the darkness that shrouds his own past… I am reminded of the famous quote from philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche that “whoever fights monsters should see to it that in the process he does not become a monster… and if you gaze for long into an abyss, the abyss gazes also into you.”

Unlike the first two parts, which balance humour, action, and noir stylings, The Trap is an introspective and unsettling descent into the heart of darkness. Stylish noir gives way to an intense neo-Gothic dread, reminiscent of the descent into madness of Harry Angel (Micky Rourke) in Alan Parker’s Angel Heart (1987).

It’s gripping right up to the frustrating final scenes that refuse to provide easy answers, instead suggesting multiple interpretations of what happened. There’s a happy ending, a bleak ending, and a surreal, metaphorical—or maybe metaphysical—finale full of ambiguity and psychological dislocation. It’s for the viewer to deliberate and decide and it might even be the end for Maiku Hama…

However, Masatoshi Nagase would reprise his role for A Forest with No Name / 私立探偵 濱マイク 名前のない森 / Shiritsu Tantei Hama Maiku Namae no Nai Mori (2002) directed by Shinji Aoyama which was also trimmed down to become the sixth episode of a concept-driven 12-part Maiku Hama television series with each episode helmed by a different director, including Alex Cox for the eleventh but without direct involvement from Kaizō Hayashi.

JAPAN | 1996 | 107 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Kaizô Hayashi.

writers: Kaizô Hayashi & Daisuke Tengan.

starring: Masatoshi Nagase, Shirô Sano, Kiyotaka Nanbara, Akaji Maro, Shin’ya Tsukamoto, Jô Shishido, Mika Ohmine, Masako Miyaji, Kenji Anan, Hai-Ping Yang, Te-Chien Hou, Haruko Wanibuchi, Eiji Okada, Yui Natsukawa, Tomoko Yamaguchi & Kiyotaka Nanbara.