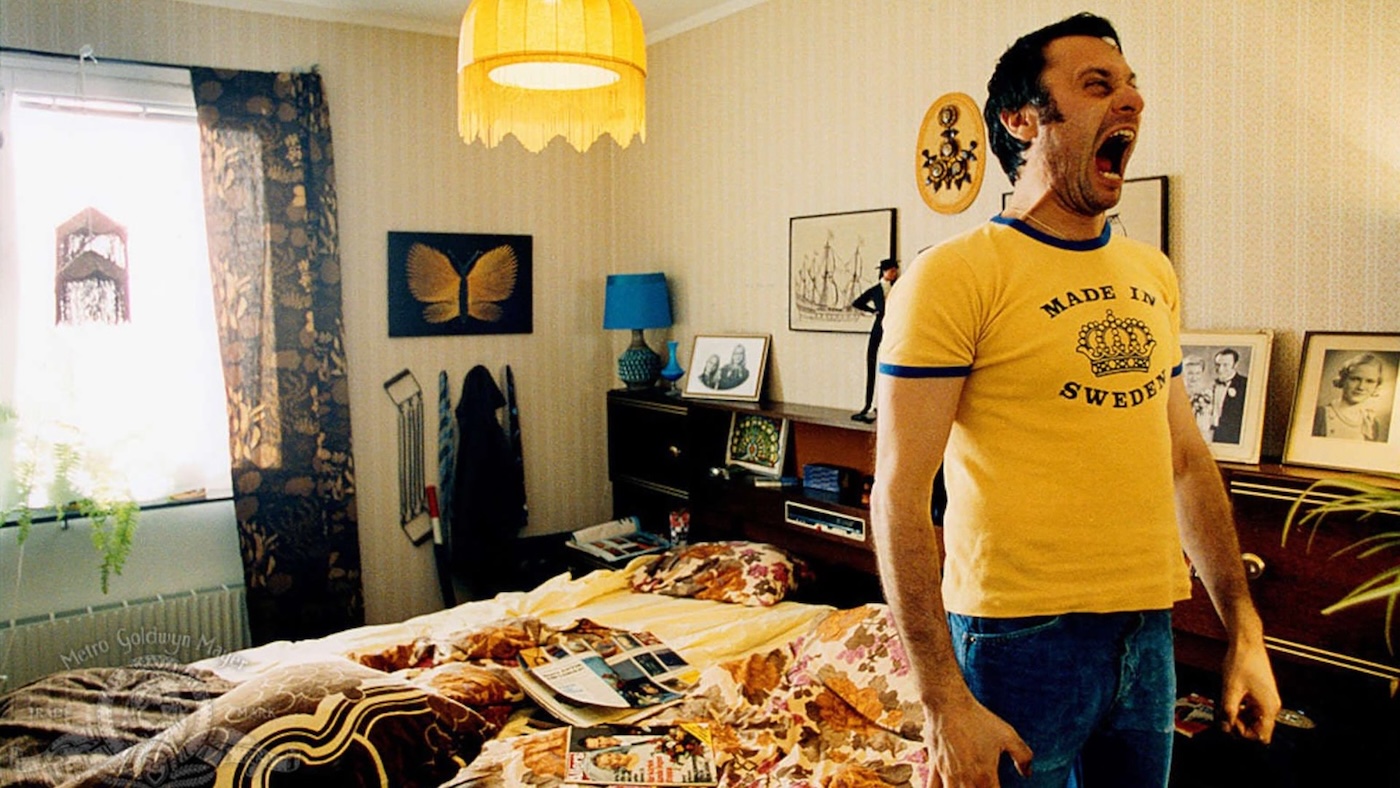

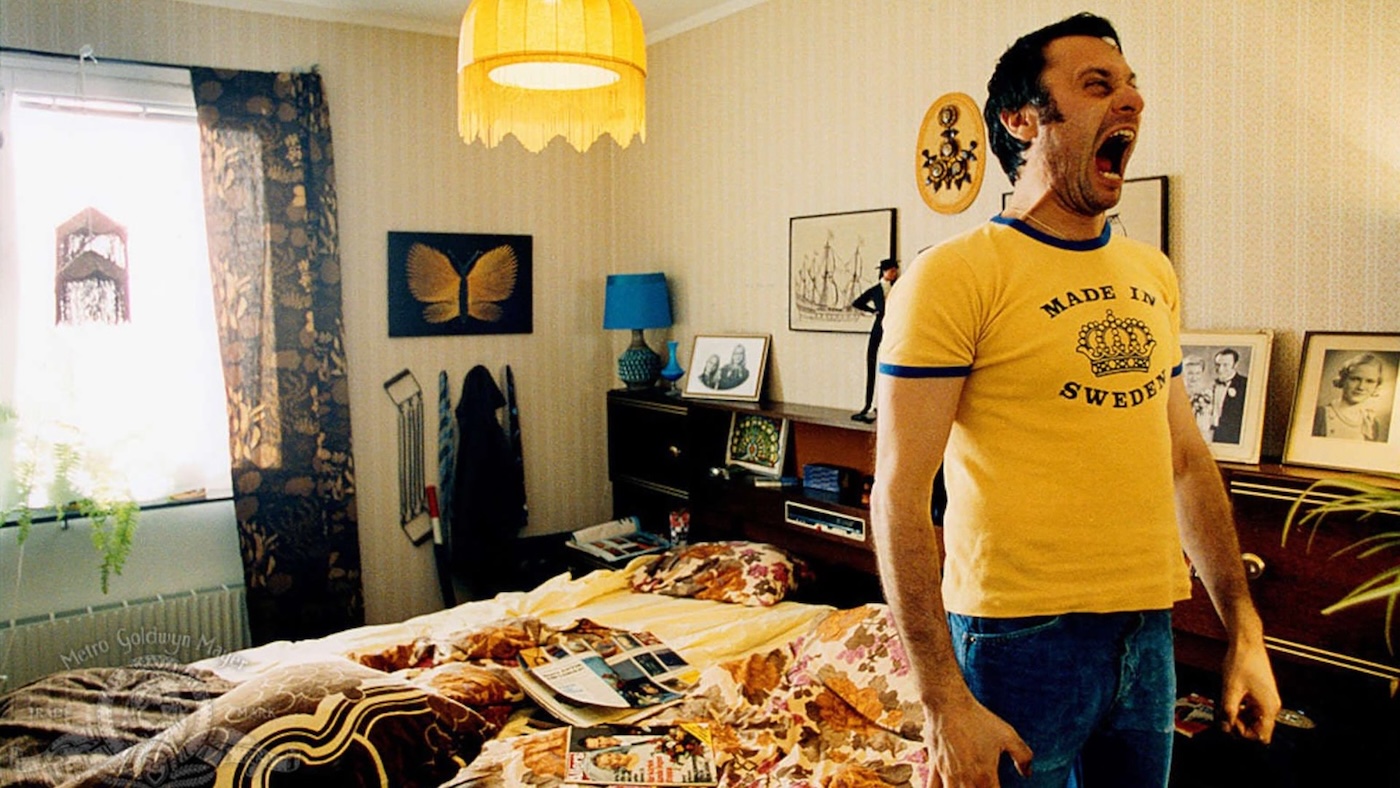

TOGETHER (2000)

In 1975, the dynamics of a Swedish commune begin to change upon the arrival of a beaten wife and her two kids.

In 1975, the dynamics of a Swedish commune begin to change upon the arrival of a beaten wife and her two kids.

Despite focusing almost entirely on the inhabitants of a left-wing commune, Together / Tillsammans is mostly apolitical. Its characters often ruminate on how to be an upstanding Marxist-Leninist or revolutionary for the cause through humorous arguments, like whether or not washing dishes counts as a bourgeois activity, or if a Pippi Longstocking book should be thrown out for promoting the pursuit of material goods. Instead of offering a serious deep dive into the ideological underpinnings of the group, this exploration of the Tillsammans (Swedish for ‘together’) commune in 1975 is a bittersweet comedy-drama that focuses on the concept of togetherness.

That said, it’s not as if the film isn’t at least mildly satirical of the attitudes of these fascinating, ridiculous characters. Unofficial group leader Göran (Gustaf Hammarsten), while explaining the benefits of the commune to two children, likens their endeavours to the porridge he’s preparing. He explains that this cooking process, like the commune, brings separate entities together and softens them, so that they operate as part of a collective. It’s a bit of a tortured metaphor, but the point is clear all the same, as Göran states that he and the other members don’t work in service of their individual desires, but for the needs of the group.

This isn’t really true for some of these members, so it makes sense that he’s the commune’s de facto leader, given that he can’t ever stand up for himself and what he wants, continually making an effort to see disagreements from everyone else’s perspective. While empathy is a desired trait in leadership, a lack of resolve is one of the worst deficiencies to possess in this role, with Göran not even having the courage to speak up for himself whenever his girlfriend Lena (Anja Lundqvist) voices her desire to sleep with other men.

As a member of the commune, technically she’s just doing her duty by being open to the needs of others and transgressing the restrictions of monogamy. Understandably, there are still barriers to total openness in place (hence why she only sleeps with members of the gender she’s attracted to). But when she does manage to persuade Göran to let her have sex with commune member Erik (Olle Sarri), her potential lover is far more interested in discussing Marxist doctrine with her than engaging in a tryst. Just because Erik can be easily persuaded doesn’t change how transparently selfish Lena is, in just one of the ways in which these characters abscond their duties on a regular basis.

Director Lukas Moodysson’s style takes some getting used to — the aggressive zoom-ins are distracting, while the frequent use of cross-dissolves is never any better than amateurish — but once you can accept the visual language on display, the experience of taking in these slice-of-life segments from each of these characters’ lives is actually quite beautiful. Moodysson knows that these commune members are worthy of being laughed at in moments, but is also clever enough to recognise that the most glorious parts of Together shine through in moments where you find yourself loving these oddballs.

While there isn’t strictly a plot, with characters slipping in and out of the story’s focus, the main storyline involves three new arrivals to the commune: Elisabeth (Lisa Lindgren), Göran’s sister and the suffering wife of the abusive Rolf (Michael Nyqvist), and her two children Eva (Emma Samuelsson) and Stefan (Sam Kessel). Our introduction to Elisabeth shows her sitting at the kitchen table with a bruised lip in the aftermath of a particularly nasty, one-sided bust-up. She asks Rolf to leave, but he stays right where he is a few paces away, refusing to spare her the indignity of having to share this space with her abuser.

The following morning the family (sans Rolf) are driven by Göran to the commune, where they will stay until they can get back on their feet. We are almost just as unaccustomed to the commune as this family unit; just like them, we’re used to normality. While the film uses this effective introduction to a unique worldview to poke fun at its characters’ ideological leanings, the greatest strength of Together is how it takes all of their interpersonal concerns seriously. The bonds and rifts that form as a result of this shake-up to the commune’s routine unearth at least half a dozen intertwining storylines, none of which take a clear #1 spot in terms of the film’s priority. They’re all equally enjoyable, mocking, and disarmingly sensitive.

An exhaustive but always entertaining night with this group is exactly what is needed to give viewers the opportunity to sink into this story. Once that happens, the zoom-ins, close-up shots, overlapping dialogue, and strong emphasis on intimacy in these scenes make them incredibly absorbing. When there’s a group of people in discussion in Together, especially in their shared house, it can feel like you’re a bystander sitting in a corner of the room, silently weighing up these characters’ interactions. Almost all of the overarching dynamics in Together feel like we’re watching these people blossom into brighter versions of themselves, like Elisabeth’s political and personal awakening about the power she holds in womanhood, aided by a new friendship with longtime commune member Anna (Jessica Liedberg). (Anna is a lesbian who is almost certainly using this kinship to seduce Elisabeth, once again prodding at the notion that these commune members only think about the needs of the group when interacting with their comrades). Stefan’s friendship with fellow commune kid Tet (Axel Zuber), where they play games like ‘Torture the Pinochet Victim’, or Eva’s infatuation with her neighbour Fredrik (Henrik Lundström), are heart-warming and hilarious.

This latter dynamic is when Together is at its most touching. Fredrik’s family is very normal in comparison to the commune, yet when one spends enough time with both family units it becomes clear that Fredrik’s parents’ conflicts are more disconcerting. The commune members might be strange, but they’re a free-spirited lot that have a much easier time recognising the quiet joys of the everyday. In Fredrik’s family, their dysfunctions become a torturous affair, since this trio exist in the same space without sharing any degree of intimacy or honesty. A pained silence permeates their evening meals, which seem to be the only time the trio are together.

Fredrik’s mother insists that her son mustn’t interact with Eva since the commune members aren’t ‘nice’, an interesting choice of words that fails to conceal her disdain for how different they are. Moodysson is also quick to show disdain, especially given Fredrik’s dad indulging in his nightly masturbation sessions to porno mags in his workshop / den, an open secret that his wife and son are aware of, but which can never be spoken aloud. This small family unit, which should possess a tight bond between its three interlinked members, is instead fraught with repression, anger, shame, and self-loathing. The cure for loneliness isn’t just other people, but good people and good company.

Aside from being elucidated in beautiful ways, this idea makes for the film’s funniest needle-drop (to an Abba song, no less), with Elisabeth’s words of defiance about how she will never again accept Rolf’s abusive behaviour spurring the meek Göran to action. He races upstairs to drag Lena outside and hurl her belongings at the confused, adulterous young woman. In reality, he’s almost as much to blame as her for not speaking up more (even though his feelings were obvious to anyone who cared to investigate, which Lena clearly didn’t), but the scene is hilariously, gloriously triumphant nevertheless.

In this film everyone is dysfunctional, but the commune members wear this on their sleeve and don’t waste time fretting over whether people will accept them. It’s not an ideal lifestyle, but perhaps that’s got far more to do with the outside world than what occurs within the walls of this shared home. Of all of these characters, it is Stefan and Eva who suffer the most, where they are ostracised at school and struggle to form connections with others due to the same strand of social pressure that caused Fredrik to be forbidden from meeting with Eva. It is the outside world that produces the disease of loneliness, but it will not rest there, bearing its ugly gaze down on two innocent children to rob them of meaningful connections.

For as much as this film only delves into politics to mock its characters’ viewpoints, the commune’s ostracisation can be easily paralleled with the difficulties of attempting to transgress a capitalist structure in a capitalist society, where communes and co-ops can seem destined for failure. In similar ways to how this film is secretly a drama hidden behind the veil of a strange, bittersweet comedy, this idea is never brought up directly, but is suffused into this film’s essence as it explores a tight-knit group living on the margins of society.

In case there are any illusions about what this film is attempting to say when it comes to isolation and interconnectedness, there’s a very telling interaction which Rolf stumbles into as he tries to become a better person. (Not that Rolf is often successful in this venture, mind, like when he gets himself arrested for assaulting staff at a restaurant he dined at with Eva and Stefan, leaving his poor children out in the freezing cold. But on the whole he makes a genuine effort towards self-improvement. Normally films that attempt to humanise abusers woefully miscalculate how to empathise with such figures, but Together is so earnest in its approach to these characters that it’s surprisingly inoffensive.)

It’s when he meets with an elderly client, Birger (Sten Ljunggren), that this storyline shines. Birger intentionally undid Rolf’s plumbing work so that the handyman would revisit his home and provide him with some much-needed company. Obliging the old man, Rolf lets Birger talk about his early life, relating an anecdote about paltry meals he would eat with his family. But now that he has no one left on this earth, he reasons that he would much rather share that depressing food again with the people he loves than dine on a delicious meal. The lives of these Marxists might not always look enviable, but in their cramped living conditions they have formed a genuine and loving family unit, which is all the more fruitful for crossing an unspoken rule in society that one must be united by blood to call your loved ones family.

While Together is not technically a Christmas film, its winter setting and emphasis on connection, camaraderie, and familial love don’t just align neatly with the themes of this holiday period, they are conveyed far more poignantly than the vast majority of works of art people defer to when they think of Christmastime. Moodysson’s follow-up film, Lilya 4-Ever (2002), is a harrowing gut-punch, depicting tortured lives and abject suffering; in comparison, Together comes across as pure fantasy. But it also presents a slice of reality that we shouldn’t be so quick to ignore or mock, with delightful characters so unabashedly themselves that simply watching them in action is a liberating experience. Replete with immersive filmmaking that invites viewers into these intimate environments and a warm, sometimes darkly comedic look at people who skirt societal norms yet cling to their loved ones tightly, Together is a rich and heart-warming film that never sacrifices entertainment value for blandly sentimental scenes.

SWEDEN • DENMARK • ITALY | 2000 | 106 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | SWEDISH

writer & director: Lukas Moodysson.

starring: Lisa Lindgren, Gustaf Hammarsten, Michael Nyqvist, Emma Samuelsson, Sam Kessel, Anja Lundqvist, Jessica Liedberg, Ola Rapace, Shanti Roney & Axel Zuber.