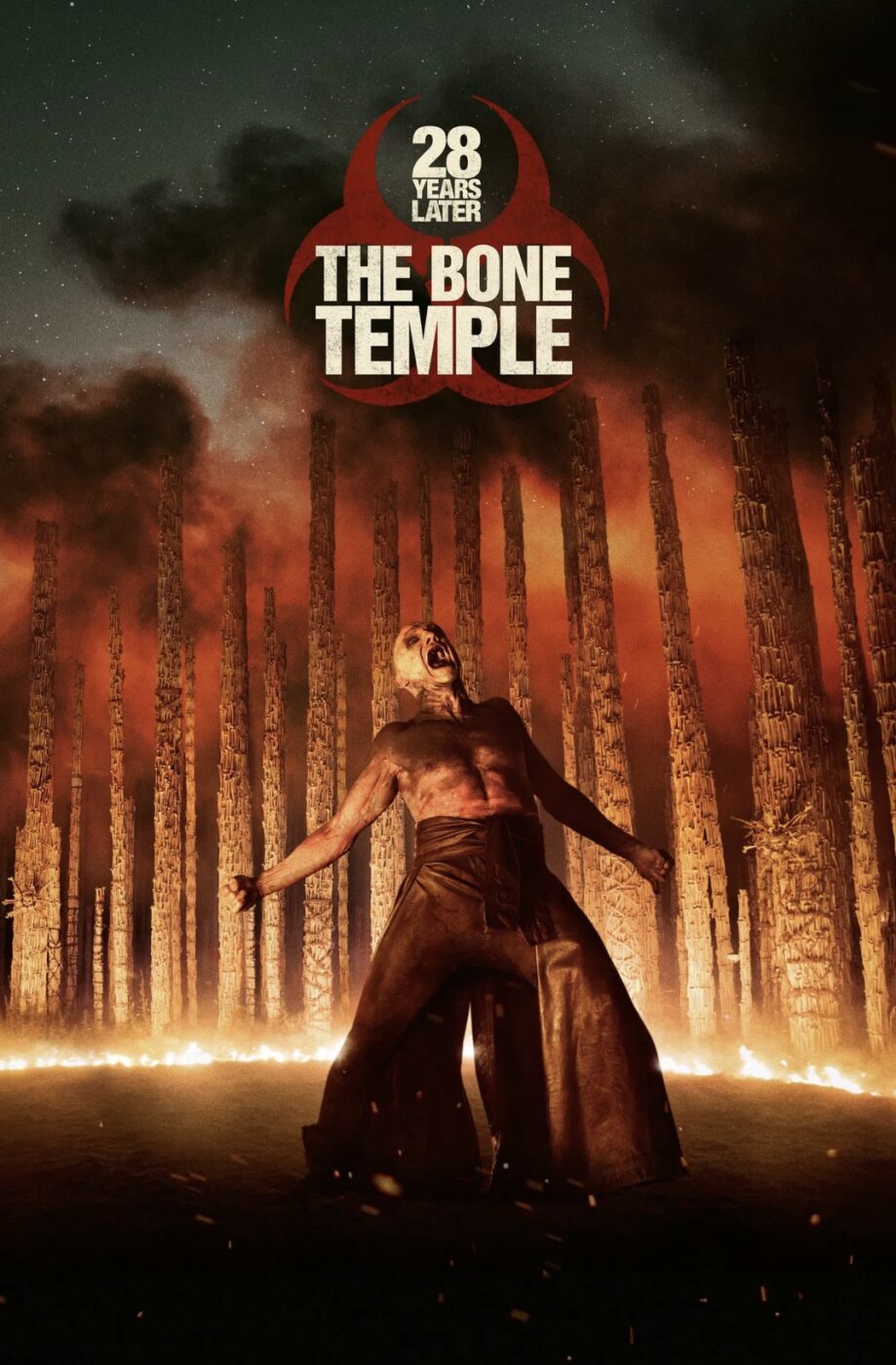

28 YEARS LATER: THE BONE TEMPLE (2026)

As Spike is inducted into Jimmy Crystal's gang on the mainland, Dr Kelson makes a discovery that could alter the world.

As Spike is inducted into Jimmy Crystal's gang on the mainland, Dr Kelson makes a discovery that could alter the world.

Given how things were portrayed and how things were left off in Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later (2025,) I didn’t have high hopes for its sequel. My skepticism grew when Boyle demoted himself to the role of producer, allowing Nia DaCosta—a filmmaker with a slim and somewhat underwhelming track record—to direct. We’ve seen this before: for 28 Weeks Later (2007), Juan Carlos Fresnadillo was handed the reins to Boyle’s original vision. The results were catastrophic; a reliance on genre contrivances and overt viscera made for a dreadful follow-up. To my surprise, however, DaCosta’s 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple is a much better affair than the first instalment.

To recap, I wasn’t a fan of 28 Years Later; it was “mid” at best. The film felt fragmented, consisting of two separate stories lethargically stitched together. Boyle’s unfiltered, avant-garde style didn’t facilitate immersion; rather, it felt jarring, leaving the audience to wonder why certain stylistic choices were included at all.

The first half focused on world-building on an island off the coast of Northumberland. It was fantastic, and I found myself wishing Alex Garland had maintained that creativity, as there was certainly more to explore. Instead, the world-building and a crucial character are abandoned halfway through in favour of an existential, coming-of-age odyssey for Spike (Alfie Williams). Rather than joining Spike on this journey to assist in his character arc, his father, Jaimie (Aaron Taylor-Johnson), seemingly decides his time is better spent elsewhere.

On paper, I like the second half, but it needed more time in the oven and proper literary tissue to link it seamlessly to the front. I’ve given Garland a lot of stick for this; I give Garland a lot of stick in general. I’m not particularly partial to his ideas, which often feel underdeveloped. However, after watching The Bone Temple, I realised the fault wasn’t his to bear.

I’ve seen him “cook” before. Boyle’s 28 Days Later (2002) was a well-crafted experience, despite minor flaws like cars defying physics. Garland’s directorial debut, Ex Machina (2015), was a compelling sci-fi drama. It’s no wonder it succeeded; he had ample time to prepare.

It was after this that I felt he lost his way. He became popular, and in the art world, corporate backing brings demands. Annihilation (2018) was an uninspired, pastiche snooze-fest; Men (2022) was so “on the nose” it was painful; and Civil War (2024) was a pathetic attempt to emulate the horrors of Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) and the war journalism angle of Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down (2001.)

Garland excels when he has the time to balance writing and directing, or when he focuses solely on the script. 28 Years Later was a disjointed mess because, as I now realise, the fault lay with Boyle. As director, Boyle has the final say. He’s an avant-garde filmmaker at heart, but in his later years, he seems to care more for unrestrained, spastic flair than using style to facilitate narrative. DaCosta, conversely, prioritises an interesting story over flair.

In The Bone Temple, Garland writes with two narrative focuses: the continuation of Spike’s journey and the story of Dr Ian Kelson (Ralph Fiennes). The two eventually converge in a great “double header” of ideological forces. Crucially, the film flips between these perspectives like a light switch, yet it never feels disjointed or poorly paced.

The film flows swiftly and smoothly. One plot follows Spike facing off against the “Fingers” gang, whom he views through the lens of the Tokusatsu programmes (like Power Rangers or Kamen Rider) he likely grew up watching. His assumptions about this filthy, blonde-wig-wearing gang are way off. They circle him, taunting him as he quivers in fear.

Their leader, Sir Lord Jimmy Crystal (Jack O’Connell), offers to induct Spike if he can kill a member of the gang. Sir Lord Jimmy refers to his followers as “fingers”—extensions of his will, which he claims is influenced by “Old Nick.” For those not in the know, Old Nick isn’t Father Christmas; it’s Lucifer. The man believes his father is the Devil, and his gaggle of miscreants reap souls in his name, believing the Rage Virus is his handiwork.

These “fingers” dress like their leader, who appears to be cosplaying as Jimmy Savile—the British DJ who became a face of absolute vileness. With hundreds of cases of sexual abuse to his name, Savile is a symbol of evil in our timeline. Fittingly, the “cosplay” includes an upside-down gold cross, while the “fingers” have the same icon scarred into their heads between the brows.

Their actions match the profundity of Savile’s evil. In a laughably clever twist, Sir Lord Jimmy refers to these acts as “charity.” They are guttural; innocents are flayed alive. The practical effects do a brilliant job of selling the reality of these images. Innocents are taken advantage of regarding sustenance, then flayed alive. The practical effects do a great job selling how real the imagery associated with their actions feels.

While I usually dislike the misuse of Christian iconography, it’s fitting here. There is a visual duality in The Bone Temple. Images of the past mean something different now. We know good intentions can mask something sinister, and these visuals extend into the characters’ very lives.

There’s a longing for the old world that exists only as fragmented memories. A grand picture can’t be formed; the suffering’s been too unyielding. Dr Kelson remembers his former life only through photographs, and Sir Lord Jimmy remembers only a single moment from the onset of the outbreak.

This duality accents the film’s theme of hope within cold indifference—a practical hope rather than an eternal one. Theology represents “philosophical suicide,” an option taken when faced with a cold universe. The two leads are paired not just ideologically, but as two people with opposite mindsets brought together by chance.

This is why the focus on Sir Lord Jimmy and Dr Kelson works. Viscera gives way to potentiality in Kelson’s story. He makes a serendipitous discovery through drug-fuelled bonding with another character. It’s a bit silly, yet simultaneously confident. I haven’t seen Garland this surefooted since Ex Machina.

Is his screenplay perfect? No. I wish Dr Kelson’s story had been given more focus, as it’s the most interesting thing to happen in this world since the initial outbreak. Nevertheless, there’s enough here to weave something truly compelling.

What I do take issue with are the moments where Boyle’s influence is visible—specifically the camerawork and editing. For the most part, DaCosta instructs cinematographer Sean Bobbitt to compose scenes conventionally. However, with Boyle as producer, some of his “flair” remains. There are moments where rapid-fire cuts are paired with camera movement that emulates Parkinson’s disease. It’s distracting.

Sometimes shots are so unconventional they become impractical, or they use modern “panning” techniques that blur everything but the subject. Our eyes don’t work like that. I hate it. Why bother composing a scene if you’re just going to blur it? There are people who’ve been affected by TikTok so much that this practice aids them in paying attention. I say stay away from the movie theatre; you’re ruining the medium.

Bobbitt also utilises the SnorriCam during chase scenes. This involves rigging the camera to the actor so they remain fixed in the centre while the background whirls. While I respect the experimentation, it’s a style better suited to soda commercials or music videos. Used between conventional shots, it feels like a blow to the head—if a powerful one, like Mike Tyson in his prime.

That is the extent of my criticism. I genuinely enjoyed 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple. It was wonderful to see Garland’s creativity flourish again, right down to the excellent use of Iron Maiden’s “The Number of the Beast”. While IMDb still lists Danny Boyle as the director for the third instalment, it said the same about this film before DaCosta was announced. I hope she remains at the helm; she and Garland make a formidable pair.

UK • USA | 2026 | 109 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Nia DaCosta.

writer: Alex Garland.

starring: Ralph Fiennes, Jack O’Connell, Alfie Williams, Erin Kellyman & Chi Lewis-Parry.