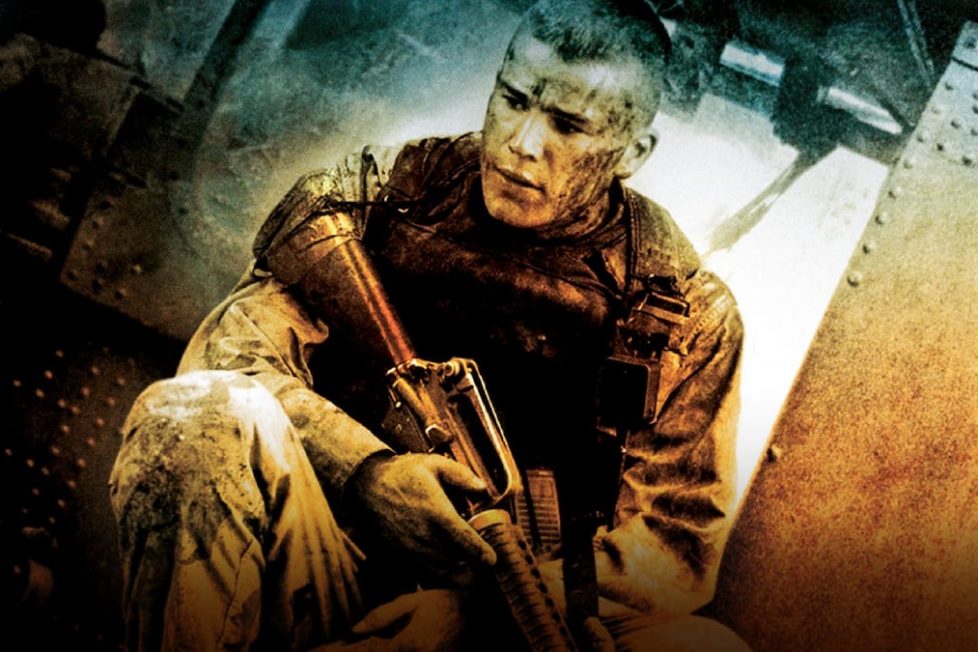

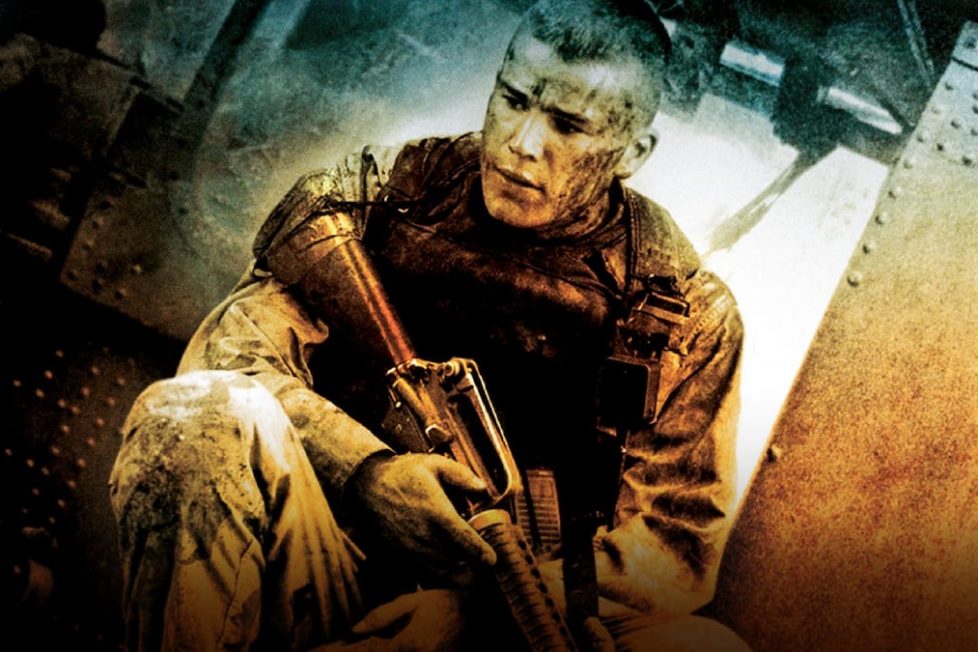

BLACK HAWK DOWN (2001)

The story of 160 elite US soldiers who dropped into Mogadishu in October 1993 to capture two top lieutenants of a renegade warlord, but found themselves in a desperate battle with a large force of heavily-armed Somalis.

The story of 160 elite US soldiers who dropped into Mogadishu in October 1993 to capture two top lieutenants of a renegade warlord, but found themselves in a desperate battle with a large force of heavily-armed Somalis.

Ridley Scott’s Black Hawk Down was nearing release in 2001 when the 9/11 terrorist attacks and subsequent US invasion of Afghanistan undermined confidence in the film. Did its tale of US soldiers fighting Muslim militia, although set only eight years earlier, now uncomfortably—even tactlessly—resemble this world crisis? Should the movie be held back?

If it had been, it’s difficult to see when it could have been released without seeming too topical, for scenarios such as Black Hawk Down’s became a familiar part of our daily news for many years after. If unintentionally, Scott’s film turned out to be prescient in its anticipation of what would soon happen in Iraq, just as its tale of a disastrous US military engagement in hostile territory clearly looks back to Vietnam (reinforced by Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child” on the soundtrack).

In any case, Scott insisted that Black Hawk Down’s fresh relevance should mean a swifter release rather than a delay, and he prevailed. But inevitably it was seen in a post-9/11 light. Osama bin Laden reportedly mentioned the film as an illustration of American weakness and vulnerability; others accused it of indulging in American triumphalism. Some found it racist in its depersonalisation of the Somali fighters in the Battle of Mogadishu, who are rarely seen close up and exist almost entirely as nameless foes; others were disappointed by its failure to develop individual characters on the US side.

Perhaps it’s a film into which you can read what you want. Certainly, it doesn’t take an obvious side—it’s perfectly easy to see Black Hawk Down as critical of American interventionism just as much as it sympathises with individual US soldiers—and it’s really better viewed as a piece of semi-fictionalised reportage, a relating of events rather than a commentary on them.

This was very much the approach that Paul Greengrass would take a few years later in United 93 (2006), a film directly based on 9/11, and the two have much in common. They do little or nothing to explore motivation. Indeed, they rarely let us into characters’ inner lives in general. They don’t heavily prioritise a few leads over other parts, and neither do they strongly differentiate turning-point scenes from connecting ones.

Both Greengrass and Scott simply let things unfold at a steady pace, the relatively trivial alongside the important, and even though they move from one group of people to another, they rarely overtly connect them to show an overall picture—the events may be large but individual moments are consistently small-scale. This is, of course, the way we experience the world, and the effect in both movies is that we come away feeling not just like detached witnesses to short incidents, but with at least some sense of what being in a certain situation might have been like.

Black Hawk Down covers the Battle of Mogadishu in October 1993, at a time when the Somali capital was considered one of the most dangerous places in the world. US troops assigned to capture two senior aides of a local general-turned-warlord became stranded in the city after two of their helicopters were shot down (hence the title), and had to defend themselves through the night against far bigger Somali forces.

19 US soldiers died, while estimates of Somali deaths range from about 300 to more than a thousand. TV images of American bodies being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu shocked the US, and President Bill Clinton began to scale down involvement in Somalia almost immediately.

Like Mark Bowden’s book of the same name, on which this film is based, Scott’s film requires close attention. The geography of the streets of Mogadishu (actually locations in Morocco) isn’t immediately obvious, the uniformed and shaven-headed soldiers are often not easily distinguishable, and yet it can be important exactly which group is on which corner of which square.

This is a strength of the film, however, or at least an inevitable consequence of its approach rather than a failing; the sense of confusion and isolation, of never being quite sure what is going on beyond one’s immediate surroundings, is a fundamental part of its atmosphere, and simplifying the details so that audiences could easily grasp everything would have greatly detracted from it.

The project to film Bowden’s book was originated by producer Jerry Bruckheimer, but although Black Hawk Down did perform well at the box office, the movie has little in common with his crowd-pleasers like Crimson Tide (1995), Con Air (1997), and Armageddon (1998). Scott is an auteur, deeply involved in the films he directs all the way from screenplay stage, and this one is very characteristic of his work: lots of scenes, lots of characters, visually complex and busy, with dialogue relegated to second place (as the film writer William B. Parrill puts it, “they are, aesthetically, silent movies.”)

Scott employed up to 11 cameras at times on Black Hawk Down, and there’s little VFX, adding to its immersion and immediacy. Yet that’s not to say that individual frames of the film are actually visually realistic. Indeed it begins, before the battle, almost in monochrome and then for the bulk of the movie the cinematography by Sławomir Idziak employs a very high-contrast, bleach-bypass style. But the unrealism is never distracting, and the palette also powerfully suggests the heat and dryness of Mogadishu.

The most important effect in Black Hawk Down, though, is nothing to do with the technicalities of filming; it’s the way that the bulk of the movie consists of almost continuous combat. Individual scenes within that can be very well done. For example, Scott’s skilful employment of movement through three dimensions in the initial raid on the building where the warlord is meeting with his advisers—but it’s the cumulative amount of gunfire and death and noise and dust and danger, rather than any particular moment, which really brings home the desperate plight of the trapped troops. Sheer duration helps too: already 144-minutes, the film gained a further seven in an extended cut.

Given all this, it’s unsurprising that few of the actors stand out much. Though they are often sketched in just enough to provide a modicum of human interest, we nearly always see them in groups rather than as individuals. The most memorable, back at HQ, is Major General Garrison (Sam Shepard); the actor-playwright wrote some of his own lines and benefits from being able to deliver them in a calm setting (though one, where he says Somalia is “much more complicated” than Iraq, turned out to be speaking too soon).

Memorable for less positive reasons are Ewan McGregor and Ewan Bremner. Neither actor is bad, but it’s difficult to see them together without thinking of Trainspotting (1996), while Tom Hardy and Orlando Bloom are among many now-familiar faces in smaller roles. But Josh Hartnett’s Staff Sergeant Eversmann is the protagonist insofar as there is one, and he also gets one of the occasional gung-ho lines that seem a little out of place in Black Hawk Down (asked if he was trained to fight, he says “I was trained to make a difference.”)

Indeed, the dialogue by screenwriter Ken Nolan (whose first produced project this was) can be a bit too pat and aphoristic. Tom Sizemore’s lieutenant colonel says to a helicopter pilot, for example, “circling above [the situation] at 500 feet, it’s imperfect. Down in the street, it’s unforgiving.” Some of the closing conversations, about men fighting for each other rather than an ideal, and not wanting to be heroes but turning out that way, verge on cliché and the obvious; the beginning of the film, meanwhile, is over-reliant on explanatory titles. (The larger context of the conflict is in fact almost irrelevant to the rest of the movie.)

Little of this matters much, though. It’s primarily Scott’s direction, occasionally flashy but not excessively so, and never less than absorbing, that makes Black Hawk Down work so well, while other elements such as production design and soundtrack enhance its impact without drawing attention away from events. Hans Zimmer wrote the original score but pre-existing music, ranging from Elvis Presley to House of Pain, is also heard.

So is a song at the beginning which to the non-expert western listener might sound generically Middle Eastern. In fact, it seems to be by the Senegalese singer Baaba Maal—Senegal is about 4,000 miles from Somalia—and to be in the Pulaar language of west Africa.

This is in itself a minor issue, but it points to the larger question of whether Black Hawk Down is too casual in its treatment of the Somalis (“skinnies”, as the US troops call them). Superficially, that might seem to be true; there is no real attempt to present them as individuals save for one conversation between an American and a Somali prisoner at the beginning and then, mirroring it, another between an American prisoner and his Somali captor toward the end.

Yet the movie does occasionally emphasise Somali civilian existence quite sympathetically. There’s the man carrying a dead child who crosses the road in front of an American convoy, for example. There are the dogs, cats and donkeys (some of them unintended by the film-makers) who wander through shots. Or there are the kids who run alongside the troops at the end (after the US have withdrawn from the combat zone) while a briefcase-clutching local talks on his cellphone—a startling scene which suddenly makes it clear that much of the city is safe, and the warlord’s zone is the aberration. This is just another, normal country temporarily ripped apart by conflict.

Most importantly, fixating on what’s not there in terms of Scott’s presentation of Somalis is missing the point. Black Hawk Down is not trying to be an even-handed documentary about the issues, but to recreate the experience of modern urban warfare, and that necessitates being subjective. Depicting both sides with equal weight would have greatly diluted its intensity, and even as it stands, it’s difficult to imagine that anyone would come out of it convinced that Somalis are “bad guys” unless they already believed that.

Black Hawk Down was divisive at the time. It attracted much praise, and Scott and Idziak were among those nominated for Academy Awards; neither won, though Pietro Scalia and the sound team did. But it also attracted much criticism for factual inaccuracies, for its treatment of both Somalis and US soldiers, and for what some perceived as shallowness. Elvis Mitchell’s savage review in The New York Times suggested that “sitting through the accomplished but meaningless Black Hawk Down is like being trapped in an action film version of Groundhog Day, condemned to sit through the same carnage over and over”, but Roger Ebert perhaps grasped the film’s intentions better when he said it would “help audiences understand and sympathise with the actual experiences of combat troops.”

And this is both Black Hawk Down’s problem and its triumph. It is an easy film to misconstrue, to take as a rah-rah, pro-war celebration of the American military (though Scott is English). But, even if Nolan’s dialogue occasionally leans in that direction, the movie as a whole doesn’t support such a reaction at all. Nothing about the fighting is depicted as remotely positive; if anything, it’s anti-war in that sense.

Primarily, though, Black Hawk Down is neither pro nor anti. It’s just saying—with steadily building force that makes it far more than the sum of a few scenes—this is what happened, this is what it was like; now you go figure what you think about it.

USA • UK | 2001 | 144 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SOMALI • ARABIC

director: Ridley Scott.

writer: Ken Nolan (based on the book ‘Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War’ by Mark Bowden.

starring: Josh Hartnett, Eric Bana, Ewan McGregor, Tom Sizemore, William Fichtner & Sam Shepard.