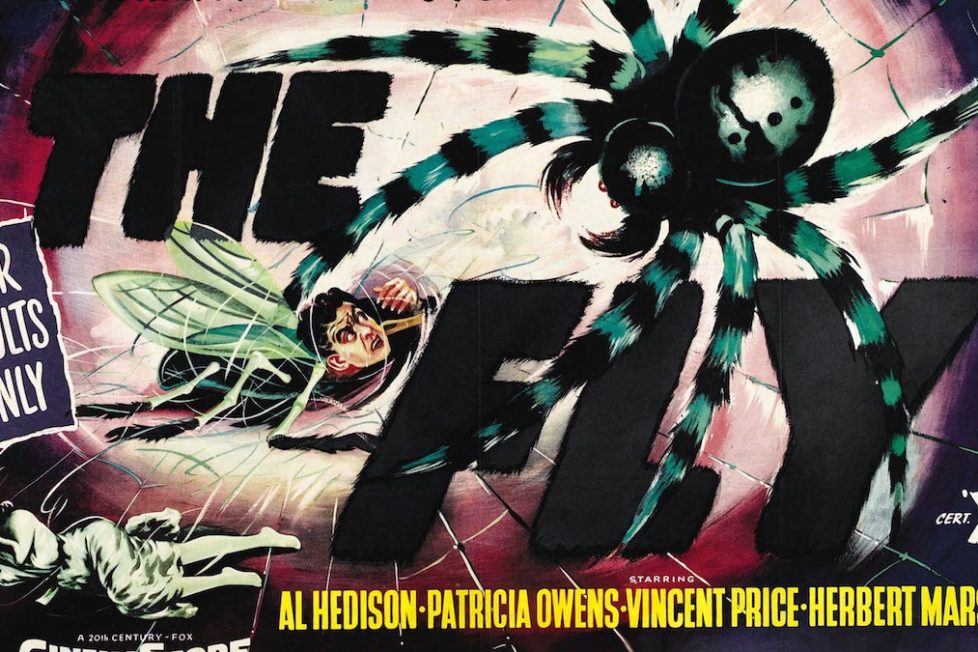

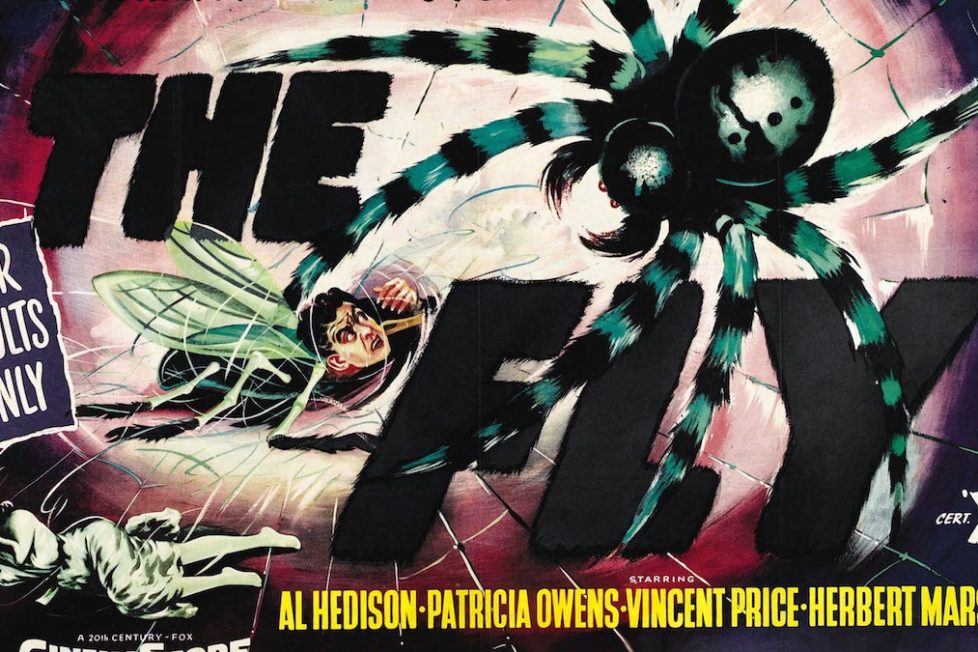

THE FLY (1958)

A genius scientist invents a teleportation device for the good of mankind, but his careless experimentation ends in tragedy.

A genius scientist invents a teleportation device for the good of mankind, but his careless experimentation ends in tragedy.

The Fly is a classic sci-fi B Movie about the hubris of a brilliant scientist, with psychological chills akin to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and themes that echo William Blake’s “The Fly”. I first saw it as a teenager on late-night television, and loved its Gothic chills and classy interpretation of future technology, juxtaposed with 1950s elegance. It posed familiar questions for the genre: does man have the right to tame the universe for his own ends? Is man at the mercy of nature? But it managed to become more cautionary tale than pure dystopian sci-fi; reflecting the aspirations as well as the pitfalls of the nuclear age. This, and the gorgeous cinemascope DeLuxe colour, make it eminently re-watchable six decades later…

When Enola Gay dropped the Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, nobody knew for sure what the ramifications would be for the environment. Suddenly, science felt godly and untamed in its power, with many Hollywood films seizing on this sense of otherworldliness to develop sci-fi stories preying on the public’s fears. The Fly is a fine example of a classic ‘creature feature’, when movies about radioactive monsters stoked mass anxiety over the threat of nuclear warfare. The film’s teleportation device seems to epitomise the power unleashed by the nuclear bomb—as its intense thrumming reaches a crescendo of bright light, which could blind those not wearing protective goggles, then disintegrates matter and slowly wreaks havoc in the body of survivors…

The experiment starts as a noble attempt to help mankind transport resources more easily around the planet, thus ending famine amongst other things, which reflects on the era’s intention to build a better world after the holocaust. The explanation that matter isn’t solid, merely electrical impulses which can be broken down and reassembled, actually echoes quantum entanglement theories of modern science. However, the familiar obsession of a genius leads to mistakes which result in a loss of physical cohesion, intellect, and soul.

The screenplay by James Clavell (later of The Great Escape) adapted George Langelaan’s short story published in Playboy magazine. 20th Century Fox executives told Clavell to ensure a happier conclusion because the original story involved a suicide, and the result certainly makes The Fly an easier watch. Clavell had been a Japanese PoW during WWII, so it’s interesting that an ashtray first teleported bears the inscription ‘MADE IN JAPAN’. Clavell includes great quotes such as “God gives us intelligence to discover the wonders of nature. Without the gift, nothing is possible.”

The Fly begins in a Quebec Factory in the dead of night with a metal press being switched on. A watchman investigates and finds a man has been crushed horribly, before glimpsing a woman running away. He phones his boss, Francois Delambre (Vincent Price), who’s just received a distraught phone call from his sister in law Helene (Patricia Owens) and, fearing the worst, Francois calls Inspector Charas (Herbert Marshall). At the factory, Francois identifies the body as his brother, Andre Delambre (David Hedison), from a war-wound scar on his leg. His sister-in-law calmly declares herself guilty of the murder, although her obsession with a fly buzzing about the room marks the beginning of a bizarre truth to the whole situation…

This was an early role for horror legend Vincent Price, who gives a sensitive performance as Francois Delambre. We first see him in his study, which has a Modigliani-style portrait of a young woman hanging over the fireplace. Price came from a wealthy family and had a degree in Art History from Yale, which adds authority to his part as a cultured gentleman who bears witness to the horrors unfolding and tries to contain them. He later pauses in front of this portrait before making the decision to convince Helene that he has caught the white-headed fly she is so obsessed with, so she will tell her bizarre truth. His white lie about the white-headed fly is out of character for this thoroughly decent gentleman… but is pivotal in unfolding the true story.

Andre appears only in flashback as a genius scientist who sweeps his wife off to the ballet then drags her down to his basement laboratory to witness his latest experiment, before treating her to champagne teleported across the room. What more could a girl want? His obsessive tendencies (such as wondering off, mid-sentence, to work on the ash tray teleportation problem, scribbling formulae on the ballet program) are compensated by his loving attentiveness at other times and his idealism. He’s filled with a love of life and the wonder of science. He looks equally good in a lab coat and black tie, too, so it’s doubly shocking when his cruel transformation is revealed…

Patricia Owens plays the ideal ’50s heroine in this her most notable role, adoring and loyal to her spouse. Their love is clear from the delight they share in simple moments in the garden and expensive evenings at the ballet. In one conversation about the teleportation device Helene seems to echo very modern fears of technology, about science going too fast and where will it all end—which Andre counters with the example of television as a good ‘magical’ invention which became part of everyday life within a generation. (60 years on, we could just as easily cite mobile phones as yesterday’s magic which has become part of everyday culture.)

Owens tackles some difficult scenes well, such as her loving responses to typewritten notes from her silent husband - who’s taken to covering his head with a sheet to disguise his monstrous appearance underneath. There’s a vain attempt to reverse the terrible metamorphosis of man into insect, but the fly’s nature slowly takes over, only held in check by the unfortunate scientist’s love for his wife. The typewritten answers to her baffled, loving queries eventually degenerate into a final scrawled message on the blackboard: ‘I love you’.

Her reaction at the sight of her half-transformed husband adds to the horror of the big reveal. It’s reminiscent of the reactions Kafka’s hero experiences in the famous story “Metamorphosis“—how long can love overcome such disgust and fear? This, and the scientist’s own failure to control his insect nature, compels him to make the decision to destroy himself and his work while he’s still in possession of his intellect. The warm domesticity of the family home above such dark deeds in the basement is another common feature of 1950’s cinema, later revisited in the deadly kitsch of David Lynch movies like Blue Velvet (1986).

Their son Phillipe is protected by his mother and uncle from this tragic turn of events. When Phillipe hurries to show his mother a cool white-headed fly he’s caught in the garden, he’s told to release it at once and “just look at the dirt you’ve brought in!” Of course, this is the all-important fly they’re hoping to catch for the remainder of the film… in a poignant scene Phillipe pats his mother’s arm when she dissolves into tears on a garden bench and reassures her that they will catch the fly tomorrow. He’s taken under his uncle’s wing for a trip to the zoo in the final scene, although he has promised he will be “an explorer like my father” when he grows up - see the inferior sequel Return of the Fly (1959) for how that turns out.

Director Kurt Neuman brought out fine performances from his relatively untried cast on The Fly - he took sci-fi seriously and was a fan of the genre, which helped him interpret the script well. These are characters we really care about, even if they’re privileged, because they’re genuinely striving to create a better and more decent world. Neuman had moved to Hollywood from Germany in the 1930s and had a long list of films behind him, including Edgar Rice Burroughs adaptations such as Tarzan and the Amazons (1945), Tarzan and the Leopard Woman (1946), and Tarzan and the She Devil (1953). The Fly was to be his last film, sadly, as he died shortly before it went on to become his greatest box office success.

The Fly was filmed in Quebec and thus has a Franco-European feel. French culture held a fascination for ’50s Hollywood—for example An American in Paris (1951). The wealthy protagonists are seen quaffing (re integrated) champagne after the ballet, crepes suzette is on a lunch menu, and good red wine (with a little water) is served even to the children over dinner. The lush colour and lovely costumes, together with the polite conversations despite the desperate situation, add to the movie’s kooky charm.

The budget allowed The Fly to be shot in cinemascope and vivid DeLuxe colour, on par with other ’50s classics such as War of the Worlds (1953). The cinematography was handled by Karl Struss, a veteran who won the first Oscar for his profession at the inaugural Academy Awards! Originally a photographer whose work appeared in Vogue, Struss moved to Hollywood and later worked with Charlie Chaplin and Mary Pickford. His art director, Lyle R. Wheeler, was known as ‘the dean’ of Hollywood art directors and had worked on an amazing array of films such as the classics Gone with the Wind (1939), Rebecca (1940), and All about Eve (1950). He gives the film a certain glamour which makes a refreshing change from current dystopian science fiction!

To this end he used technicolour to contrast the affluent family home (filled with elegant pale furniture, lustrous upholstery and pastel drapes) with the Hades-like setting of the basement laboratory (all shadowy dark cold blues with the occasional blood red.)

Costume designer Charles LeMaire had worked with Wheeler on The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951). His other credits included many ’50s classics including Marilyn Monroe films The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Bus Stop (1956). so it’s no surprise that Helene’s costumes, from her silvery ‘going out to dinner at my husband’s colleague’s place’ to the glamorous full length evening dress which she wears to the ballet (worthy of singer Katherine Jenkins), and the white high-collared dress she wears about the house, are all beautiful. Her costumes echo the pale and warm pastel tones chosen for the home décor.

Even her husband’s horrific prosthetic fly head has a certain beauty, with the lustrous colour of its compound eyes and little tremulous movements of its proboscis—more chilling because it is attached to a body still dressed in neat shirt, tie and lab coat…

Ben Nye was brought in as the make-up artist, having previously worked with Wheeler on with The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) also. His later credits included Our Man Flint (1966) and Planet of the Apes (1968).

There was a revised body horror remake of The Fly in 1986 by David Cronenberg, which starred Jeff Goldblum, and there are rumours JD Dillard (Sleight) may remake this version for 20th Century Fox, which suggests this original film’s concept is as vibrant in our imagination as ever…

In short, The Fly tackles big questions that are still relevant. It also has a fly-headed scientist greedily guzzling a bowl of milk laced with rum beneath a blanket, so what more can you want? Understated visual effects, like the compound eye view of his wife screaming at the sight of her transformed husband, together with over-the-top effects, like the tiny human-headed fly and giant spider, are just brilliantly conceived and executed. This is a treat to watch, even 60 years after its release.

director: Kurt Neumann.

writer: James Clavell (based on a short story by George Langelaan).

starring: Al Hedison, Patricia Owens, Vincent Price & Herbert Marshall.