SMOOTH TALK (1985)

A teenage girl is wooed by a young man who may not be what he claims...

A teenage girl is wooed by a young man who may not be what he claims...

When filmmaker Joyce Chopra first read the short story Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? by Joyce Carol Oates, she found it frightening, and unsurprisingly so. Even if it’s not entirely clear what happens at the end to its teenage protagonist, and even if the reader didn’t know Oates had based the man whom this girl meets on the exceptionally peculiar mid-1960s Arizona serial killer Charles Schmid, there are strong indications that not everything about him is quite right.

He could be a murderer, or he could perhaps be the devil or something else supernatural, either in reality or in a dream. And though the story’s ambiguous ending doesn’t necessarily imply the protagonist’s death, and Oates herself said the man wasn’t necessarily a killer, most readers will—like Chopra—be left with that impression.

The initially disturbed Chopra, however, decided to take Oates’s premise in a slightly different direction for her film adaptation of the story, Smooth Talk, and with her screenwriter husband Tom Cole she put more effort into developing the character of Connie (Laura Dern). According to Chopra, “[teenage girls were] a subject I still felt deeply connected to”, as she’d made the documentary Girls at 12 (1975) and, equally importantly, had a daughter of her own.

While the older man posing as a teenager, Arnold Friend (Treat Williams), remains an unsettling and threatening figure, Chopra chose to leave out a suggestion Connie might have to sacrifice herself to protect her family, and instead opted for a more definitive and positive ending than the book (while still preserving Oates’s point that Connie in extremis realises family might be more important than flirting with boys).

So Smooth Talk the movie is a distinct work that builds on the ideas, premise, characters and milieu of Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? rather than translating them directly to the screen. Still, not only do Chopra and Cole use some dialogue directly from Oates’s story and preserve its flavour effectively, but watching the film is a rather similar experience to reading the story. Both are quite short and seemingly simple, concealing depths of meaning beneath a very uncomplicated narrative.

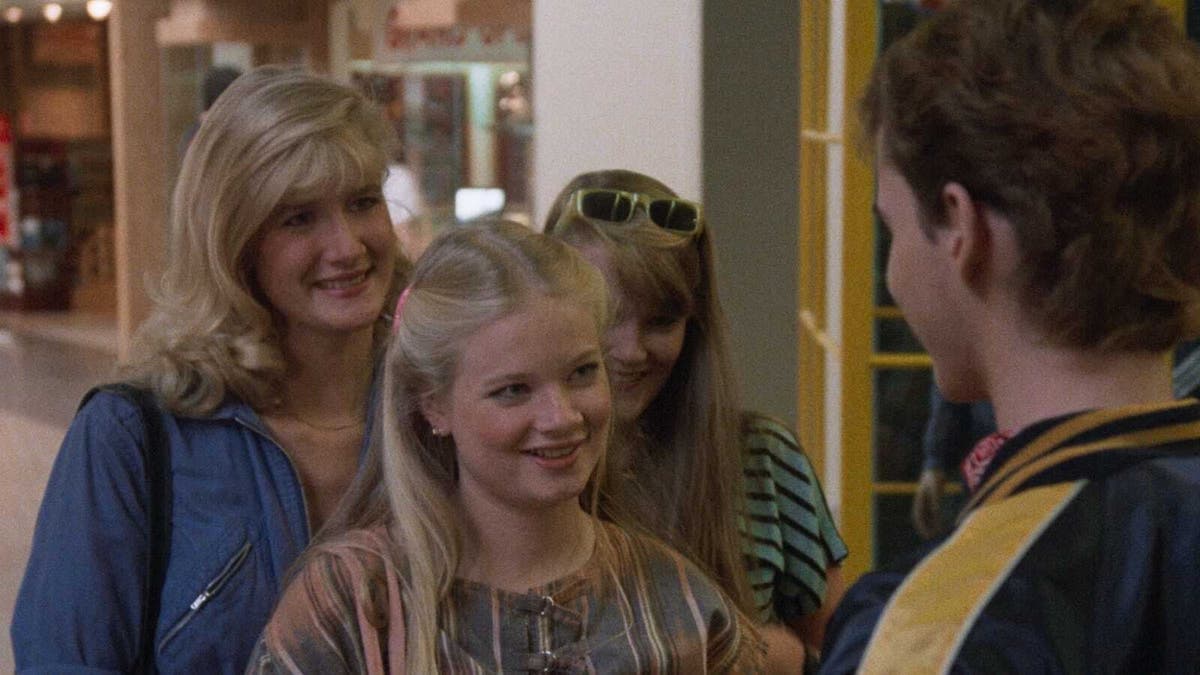

Smooth Talk opens with three girls—Connie, Laura (Margaret Welsh) and Jill (Sara Inglis)—lazing on a northern California beach, suddenly realising they risk being late getting home and hitching a lift with a strange man to make it back in time. An earlier version of the screenplay had led into this rush home more gradually, showing more of the girls hanging out on the beach beforehand… but by diving straight into this minor crisis, the film establishes a sense of anxiety almost immediately, and the casual way in which they climb into a stranger’s truck also prefigures the climax.

It soon becomes clear the principal character is Dern’s Connie, and she’s the only one of the three girls whose home life we see. It’s not an especially happy life, though maybe only unhappy in the way of a typical dissatisfied teen; Connie paints her nails, mopes, dreams, flirts with herself in the mirror, and rehearses lines to use on boys. She spars with her mother (an outstanding Mary Kay Place), who exasperatedly asks “Do you ever think about anybody except yourself?” It’s a fair point. Connie is entitled, complaining when she has to wait just 15 minutes for a ride.

But much of the film continues to feature the whole trio. For example, going to the mall to meet boys (and then being terrified when a couple of young men actually do come on to them), or going to Frank’s diner for the same purpose, along with dozens of other high schoolers. It’s at Frank’s that an older man in shades (Williams’s character Arnold Friend, though we don’t know his name yet) comments, apparently jokingly, that “I’m watching you.” It’s also at Frank’s that Connie hooks up with another boy (William Ragsdale), who drives her to a spot overlooking the city to make out.

“This is so beautiful,” she says, though it isn’t particularly beautiful, as one can tell she feels she ought to say it. Before long she’ll also be relating how romantic her tryst with yet another boy, Eddie (David Berridge), was… although it was actually a flop and not at all romantic. Again, Connie so much wants romance (or believes she ought to want it) that she’s determined to go through the motions of being smitten, even when her real feelings are different. Perhaps she’s being more honest when she tells Eddie that “I wish I could just travel somewhere.” The place she really wants to travel to is adulthood.

Smooth Talk continues along these lines for quite a while—the girls being teens, Connie squabbling with her mum and her older sister June (Elizabeth Berridge)—and, while it remains quite absorbing thanks to nearly flawless performances and a script which constantly throws up little surprises and intriguing insights, it begins to seem almost plotless.

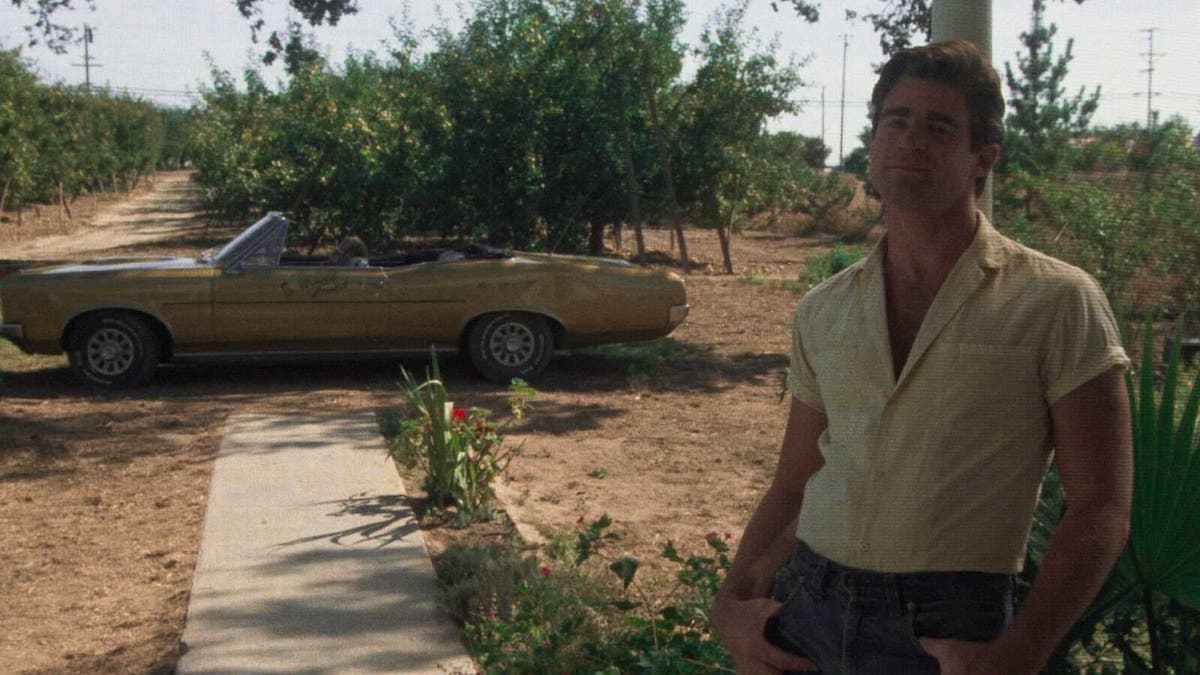

However, it then takes a far stranger and darker turn when Arnold Friend turns up in his gold-coloured convertible at Connie’s home while the rest of the family is out at a BBQ, and demands she go on a date with him. This is the dramatic core of the film (and the short story) to which everything else has been, really, just a scene-setting and character-establishing prelude. To talk in detail about what happens would be to spoil it… but, suffice to say, Arnold Friend is accompanied by his pal, Ellie (Geoff Hoyle), whose throwaway line “you want me to pull out the phone?” (meaning he could disconnect the landline, not produce a mobile…) provides the film’s most overtly chilling moment.

If Smooth Talk is largely about Connie, the character of Friend is nevertheless key to it as well. He’s impossible to fully fathom—both for her and for us, though there’s also a gap between what we instinctively understand about him and what Connie sees. At first, she mostly fails to perceive the threat that Friend might represent; her experience of boys and dates has been so filtered through her romantic longings that her concept of them is almost completely divorced from actuality.

Friend himself must also know he’s a mystery and almost inexplicable. Who is he? Where did he come from? Why did he pick Connie? How does such an obviously older guy get away with posing as a teen? He “had come from nowhere before that and belonged nowhere”… “his whole face was a mask”, Oates wrote.

Yet he acts toward Connie as if the overtures he is making to her are the most normal thing in the world—as if he is, in fact, a natural and reasonable-to-expect culmination of her romantic hopes. Only relatively slowly does Smooth Talk make it clear, to us and to Connie, that she may not really have an option where his proposed date is concerned. Her dreamy world and the harsher real one have, finally, collided; both Williams’s acting and the way he’s shot become progressively but subtly more sinister as the film progresses, something we don’t notice happening until the transformation is complete.

Chopra wanted Williams for the role of Friend from the beginning, and like everyone in Smooth Talk he’s perfectly cast, using his body as much as his face and dialogue to express Friend’s attractive yet unpredictable and dangerous personality.

At times the final section where Friend visits Connie’s house is almost balletic—Chopra described it as “a sinister courtship dance” in which “Treat used his shiny gold convertible almost as a third person in the scene”, and indeed space is vitally important here. The simple question of whether Connie will move from one side of Friend’s car to the other, going further into “his” territory, becomes as significant as the possibility of him forcing his way into her house.

Dern uses physical acting to great effect in this section of the film, too. Note the way she grips the woodwork of the house when she’s about to depart, as if desperate not to leave the security of home behind. Throughout the movie, she creates much of the character of Connie through little details of manners and facial expressions.

Although she does seem a tiny bit old for Connie (she was nearly 19 when the movie was released) Dern masterfully captures the teenage awkwardness which Oates pinpoints: “Everything she said sound[ed] a little forced, whether it was sincere or not”; “everything about her had two sides to it, one for home and one for anywhere that was not home”.

Again, her abortive romantic/sexual encounter with Eddie—the one about which she rhapsodised afterwards, despite it being anything but rhapsodic—encapsulates her conflicted emotions and her uncertainty about which of them she should trust. She simultaneously enjoys it and pretends to enjoy it while actually wishing she wasn’t there. “I’m not used to feeling this excited,” she says, summing up her own confusion. Equally telling is another scene, at Frank’s, where Connie’s composure slips amid her nervousness among so many boys, confirming that her attempt at coolness is just an act.

Another fine performance, in a film full of them, comes from Place as Connie’s mother, a bright and sometimes sarcastic woman rather reminiscent of Lisa Eichhorn playing a similar role in Cutter’s Way (1981). We get the strong impression that she, too, was young and pretty not so long ago but is now disenchanted by life as a stay-at-home mom, forever trying to paint their house (and surely never going to get it finished).

Her critical comment to Connie that “I look right in your eyes—all I see are a bunch of trashy daydreams” is born of experience that those daydreams won’t come true, and one of the best moments in the film is a cut from Connie dancing in her bedroom to her mother doing the same, to the same music, but in a different room and more wistfully. Here more than anywhere it is clear that her mother’s life may well be Connie’s future, and Connie’s present is her mother’s past.

Also effective, though in a less emotionally rich and slightly more humorous role, is Levon Helm as Connie’s father: a cheerful enough but decidedly old-school guy who thinks that paying for the house and the groceries is his only responsibility toward the family, assumes that his wife has nothing much to do all day, and complains when he gets tuna salad for dinner (it’s not a real meal if it doesn’t involve meat and potatoes, presumably). He’s impossible to dislike, but completely disconnected from reality, believing the big risk in going to Frank’s to meet boys lies in crossing the busy road outside the diner. In his own way, he’s as unrealistic as Connie.

Among the rest of the cast, Elizabeth Berridge as June (older than her sister Connie but much more of a homebody), Welsh as Laura, and Inglis as Jill (less boy-obsessed and more genuinely independent-minded than Connie and Laura) are all strong, while Hoyle’s Ellie is suitably weird in his small role (and remarkably the actor was about the same age as the “40-year-old baby” Oates describes, though he seems much younger).

As for music, there’s an understated conventional score credited to Russ Kunkel, George Massenburg and Bill Payne, but most of the impact comes from diegetic songs; these include several by James Taylor, of which “Handy Man” stands out, while other artists include Franke and the Knockouts.

With all the performers, we get the feeling the film isn’t quite inside them, that we’re never fully grasping what makes them tick (and perhaps they don’t themselves). There’s something deeply lonely and distant about the character of Connie, in particular. Frequently shot by Chopra on her own in the frame, she has little real interaction with anyone beyond her family and her few girlfriends, and even that it’s mostly on the level of joshing or moaning or bickering. Chopra, who was interested in editing, heightens this effect of detachment with a very unhurried style.

Settings are also important in Smooth Talk, although there are few of them. “A location told the story as much as the dialogue did,” Chopra wrote, and the movie manages to make these rather drab and anonymous locales pungent with meaning in exactly the way they would seem to a teenager who had rarely ventured beyond them.

The American critic Vincent Canby has suggested that the nondescript suburbia of Smooth Talk–-there is no obvious downtown, there are no landmarks—parallels the lack of a centre in its characters’ lives. It has also been pointed out that the world of the film seems more like a series of idealised teen-movie locations (the wonderful diner, the idyllic beach, the fun mall, the oppressive home) than complicated, ambiguous reality, and nowhere is this more true than in the treatment of Frank’s diner, a gathering spot almost bubbling over with excitement and opportunity, which Oates describes as “a sacred building.”

Away from the diner, though, the unreality can be less enticing. “The kitchen looked like a place she [Connie] had never seen before”, Oates wrote, and certainly none of Connie’s home seems warm or familiar even though it must be to the characters.

At least, this is true for most of the film: Chopra’s skill as a director is evident again toward the end where Connie’s house and her father suddenly seem to be sources of relief rather than irritation or alienation, and the genuineness of her parents’ affection for her comes into clear view. The contrast of mood is striking even though nothing has changed in broad stylistic terms; it’s all achieved through subtle touches.

Like Oates’s story, Smooth Talk is open to several different readings. A feminist narrative about predatory, exploitative males is obviously there, but while the film is specifically about girls and would undeniably be a different one if it was about boys, it also has much to say about the teenage years in general and that odd state of suspension between childhood and adulthood. It addresses, in particular, the way western culture at the time (and even now) elevated unrealistic ideas of romance and sex, simultaneously venerating them as things of almost mystical perfection and reducing them to the level of consumer goods.

Connie’s inability to make sense of these contradictory messages accounts for much of her unhappiness, and part of what makes Smooth Talk (almost as much as Oates’s short story) so haunting is the possibility that the roots of tragedy could be so trivial. The way that Connie cannot recognise the dangers—emotional and perhaps ultimately physical—beneath the superficial positivity of her world is a source of poignancy in itself.

Smooth Talk is an unusual film, one where very little happens for a long time, then something momentous seems suddenly about to happen; a film where we follow a small group of characters, and one in particular, in detail for the entire running time and feel we know them as well as anyone could, but also get the sense that they are not letting us—or anyone—really in.

It must have puzzled audiences in 1985 who were expecting a more straightforward teen movie. Or, for that matter, a more traditional emotional drama. But it’s precisely this way that Smooth Talk gives us such a different angle on relatively familiar material—as well as Chopra’s direction, the imaginative writing, and the terrific cast—that makes it such a gripping and memorable movie.

USA | 1985 | 92 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

Surprisingly, Criterion’s new Blu-ray disc doesn’t include a scene-by-scene commentary, but there are more than enough other extras to make up for that shortcoming.

director: Joyce Chopra.

writer: Tom Cole (based on the short story ‘Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?’ by Joyce Carol Oates).

starring: Treat Williams, Laura Dern, Mary Kay Place & Margaret Welsh.