CUTTER’S WAY (1981)

A young Californian man and his friends suspect a local business magnate of murder.

A young Californian man and his friends suspect a local business magnate of murder.

Nominally, Cutter’s Way (originally known as Cutter and Bone) may be a movie of the 1980s, but the Newton Thornburg novel on which it’s based was published in 1976 and in spirit the film belongs to the 1970s too. One could see it as a sourer, more disillusioned successor to Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show (1971), for example, or a less overtly melodramatic riff on themes in Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter (1978).

Suffering from a half-hearted release by an uncertain studio, it nevertheless earned immediate acclaim from critics of the time, so its relatively low profile today is difficult to explain. The fact that Ivan Passer, its Czech-émigré director, never became a big name may be one factor, but those who do know the film often hold it in high regard, and Radiance’s new Blu-ray rerelease—with a good transfer and some worthwhile extras as well as less compelling ones—will bring it to a wider audience.

Cutter’s Way is often described as a noir, though this may raise some erroneous expectations; a lot of it’s bathed in bright sunshine, and the principal characters aren’t as morally compromised. If anything, Jeff Bridges’ is forced away from compromise, and while there’s possibly evil in the shape of Stephen Elliott’s villain, it’s not the primary focus.

But this probably reflects the vagueness of definitions of noir as much as anything else, and Cutter’s Way certainly does have characteristics associated with the style: an ever-present sense of danger, a strong sense of place (Santa Barbara, California), and a sense of there being something profoundly wrong with the world.

“Everything [in Cutter’s Way] is broken,” says Nick Redman on one of the commentaries, and a sense of disappointment does indeed pervade the film, from the wage gaps of Santa Barbara itself to the frustration of John Heard’s Vietnam veteran. The film can be nostalgic for a better past, too, but its emphasis is largely on the imperfect present.

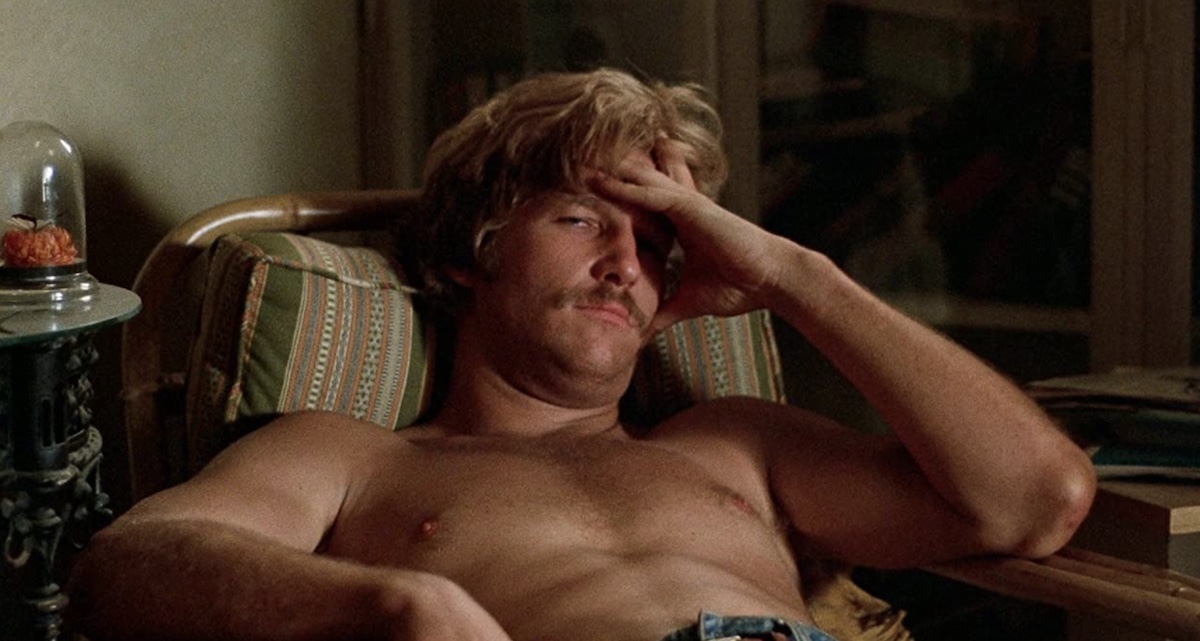

Passer’s film, which has some substantial differences from the Thornburg novel, starts in black-and-white—suggesting the past, of course—-but the fiesta on the Santa Barbara streets it depicts is gradually colourised. Perhaps this celebration, and the glamorous blonde dancing in the foreground, are the city’s unrealistic image of itself? For the music feels more distant than it should, with a touch of unease, and the fiesta scene is soon replaced by less glamorous present reality: Bone (Bridges) in a hotel room with an older woman (Nina van Pallandt in a fine cameo), the pair of them clearly post-coital and he apparently expecting payment, though it’s dressed up as a loan to save face.

Bone, it turns out, lives on a boat and works as a salesman for the boatyard, but hangs out most of the time with Cutter (Heard) and his wife Mo (Lisa Eichhorn). There’s evident unspoken tension in the trio, with Bone and Mo relatively well-behaved, and close to each other, while Cutter is a hard-drinking, fight-starting loose cannon—at one point provoking a group of black men in a bar with the n-word, though he seems to be doing it purely to get a reaction. When the boatyard owner (Arthur Rosenberg) brings him home drunk, everyone smiles, but they’re obviously uncomfortable.

One night, Bone’s car breaks down in an alley, and is passed by another car, in which he glimpses a man. Unknown to him until the police visit the next day, the body of a young woman had been dumped in the alley—we see it momentarily in a trash can, high heels protruding—and, because his car was left nearby, he’s under suspicion.

This is one of a few points where Cutter’s Way doesn’t really stack up in strict plot terms, because a murderer would surely take care not to leave his vehicle near the body, if anything… but maybe Bone is a suspect simply because he’s something of a layabout. More important, in any case, is that at a civic parade shortly after, Bone is convinced he recognises the man from the passing car: J.J Cord (Elliott), a powerful local business owner.

Cutter and the victim’s sister (Ann Dusenberry) are adamant this points to Cord’s guilt; Bone is less sure; and the bulk of Cutter’s Way concerns both their amateur investigation into Cord and the question of their own motives. Does Cutter truly believe Cord is the killer, or is he just attracted to the idea of bringing down a prominent member of the establishment? Does Bone think Cord might be innocent, or—given his own lack of commitment to anything much—does he just not want to get involved?

There are shocks later on, before an abrupt but impactful ending (which briefly even veers close to fantasy, with Cutter on a symbolic white steed), but these issues and their effects on the characters’ relationships are the film’s central thread.

The people, then, are the key to Cutter’s Way, and two performances stand out in particular. Eichhorn as Cutter’s wife—and Bone’s soulmate—is magnificent (somewhat reminiscent of the young Jodie Foster) as a strong, sad woman who hasn’t got what she expected from life. She and Bone have the film’s tenderest moments together (“when I wake up in the night and I can’t sleep, I have to go and look and see if I’m still here”, she tells him) but most of the time she refuses to display any weakness, and she can be angrily sarcastic about Cutter’s increasingly elaborate plans to unveil Cord as the murderer.

Heard’s Cutter is a more flamboyant character, annoying but sharp (hence his name, where Bone is a little bone-headed?), an amputee Vietnam vet who seems to seek friendship and reject it in the same breath. He professes lofty ideals (“he feels the world’s short of heroes, he’s trying to fill the gap”, Bone says), but he can also be consumed by resentment. One of the movie’s most intense passages is his monologue at the parade, jocular but embittered, while a brilliant scene where he deliberately infuriates a neighbour before sweet-talking a cop round to his side of the argument suggests he may always be acting a part.

Eichhorn and Heard give two of the greatest overlooked performances of the period here. Bridges, a much better-known name than either, might seem bland by comparison but that is intentional; his Bone, an Ivy League graduate turned part-time casual gigolo and full-time moocher through life, is largely motivated by dodging any kind of responsibility. “Sooner or later, you’re going to have to make a decision about something,” he is told. But perhaps he is only avoiding reality in a different way from his friend Cutter, whose view of the world often seems a fantasy.

More grounded than either are the characters of the boatyard owner (Rosenberg), a man whose quiet delicacy contrasts with his stature, and—when we finally meet him—Cord, who’s undeniably sinister whether or not he’s guilty of murder. For most of Cutter’s Way he looms silently, and it is only toward the end that he speaks to the protagonist… and removes his sunglasses. Dusenberry as the sister of the murder victim, meanwhile, raises questions herself: is she not a bit too eager to become involved with the schemes of Cutter, a stranger to her? Is she really after justice, or does she see a way to make money out of her sister’s death?

Passer, who had collaborated several times in his native Czechoslovakia with Miloš Forman but never became a major Hollywood figure despite a busy career through the 1980s and 1990s, directs naturalistically with a sure but unobtrusive touch; after the obvious artifice of the monochrome opening the photography never draws much attention to itself, and even the more elaborately structured or physically dramatic scenes come across as entirely plausible.

Much more noticeable than Passer’s direction, in fact, is the striking score by Jack Nitzsche, whose previous credits included One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), as well as a contribution to the limited amount of original music in The Exorcist (1973). Here he provides a delicate, moody accompaniment just right for the film’s tone, with much use of unusual instruments including the saw and glasses (as in Cuckoo’s Nest).

The description of Cutter’s Way by Bertrand Tavernier (in one of the extras here) as the “best film about post-Vietnam America” might be overstating things; arguably a huge amount, if not all, serious American film since the mid-’70s has been at least partially about that. But absolutely it is an absorbing, eloquent movie, its storyline not at all weak but its characters and its sense of place and period even stronger; the two superb performances from Eichhorn and Heard, as well as its memorably haunting atmosphere, entitle Cutter’s Way to the overused description “neglected classic.”

USA | 1981 | 109 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Ivan Passer.

writer: Jeffrey Alan Fiskin (based on the novel by Newton Thornburg).

starring: Jeff Bridges, John Heard, Lisa Eichhorn & Ann Dusenberry.