YIELD TO THE NIGHT (1956)

A young woman who's been abused by all the men in her life, finally finds someone she believes loves her, but snaps when she finds out he's a cheat.

A young woman who's been abused by all the men in her life, finally finds someone she believes loves her, but snaps when she finds out he's a cheat.

Still compelling and poignant nearly 70 years after its release, and almost as long after the social reform it pleaded for was finally achieved, Yield to the Night is celebrated for giving Diana Dors a rare serious role. The British actress (then known as a “glamour girl” and even nowadays frequently compared to Marilyn Monroe) is cast utterly against type as a convicted murderer, and for much of the film she’s emotionally dishevelled and physically drab; her unmade face and plain prison garb the polar opposite of Dors’s usual bouncy, glitzy persona.

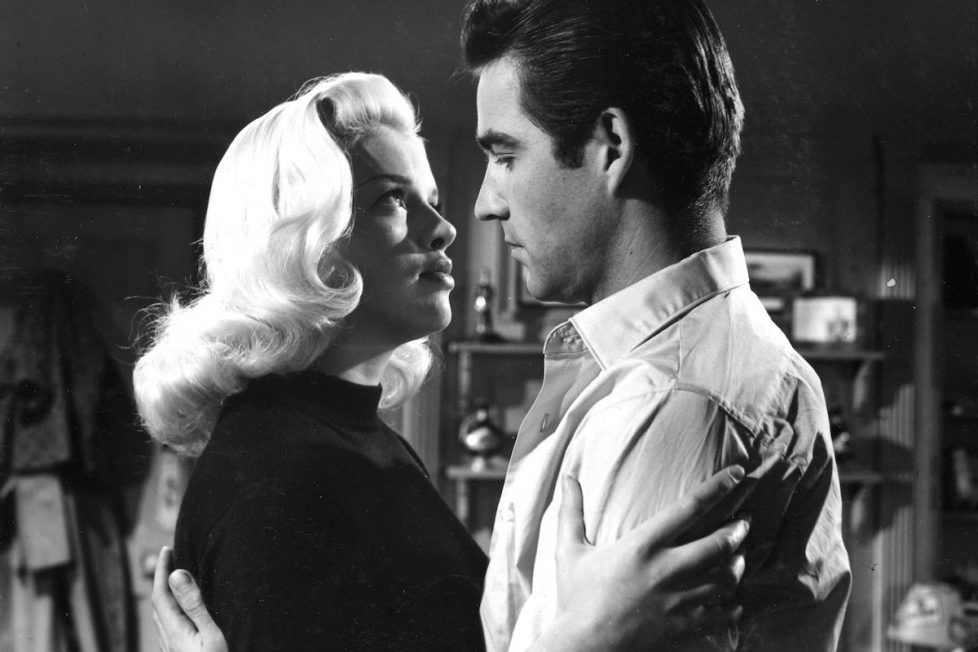

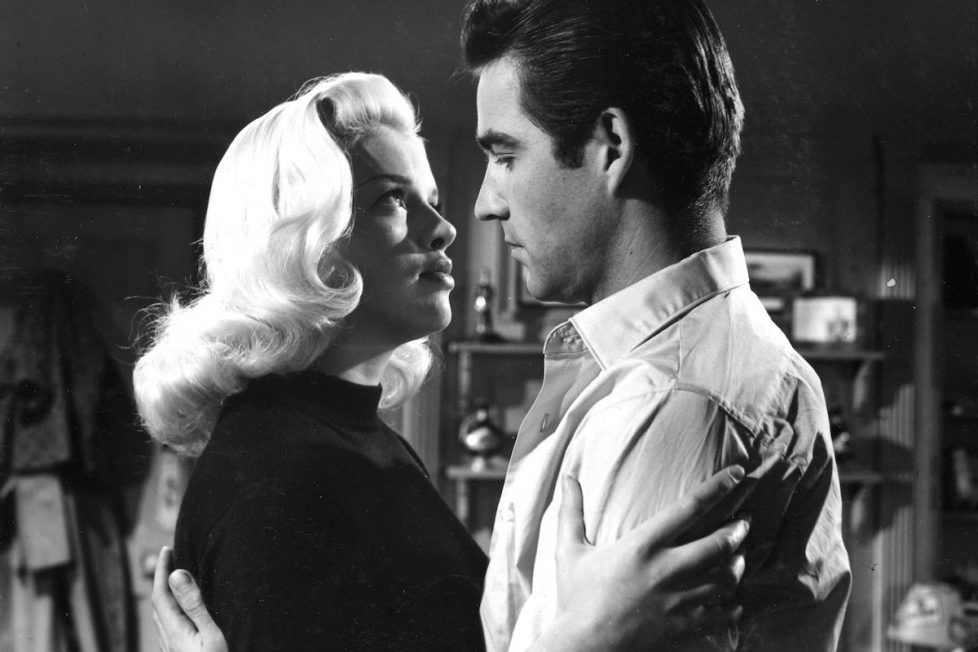

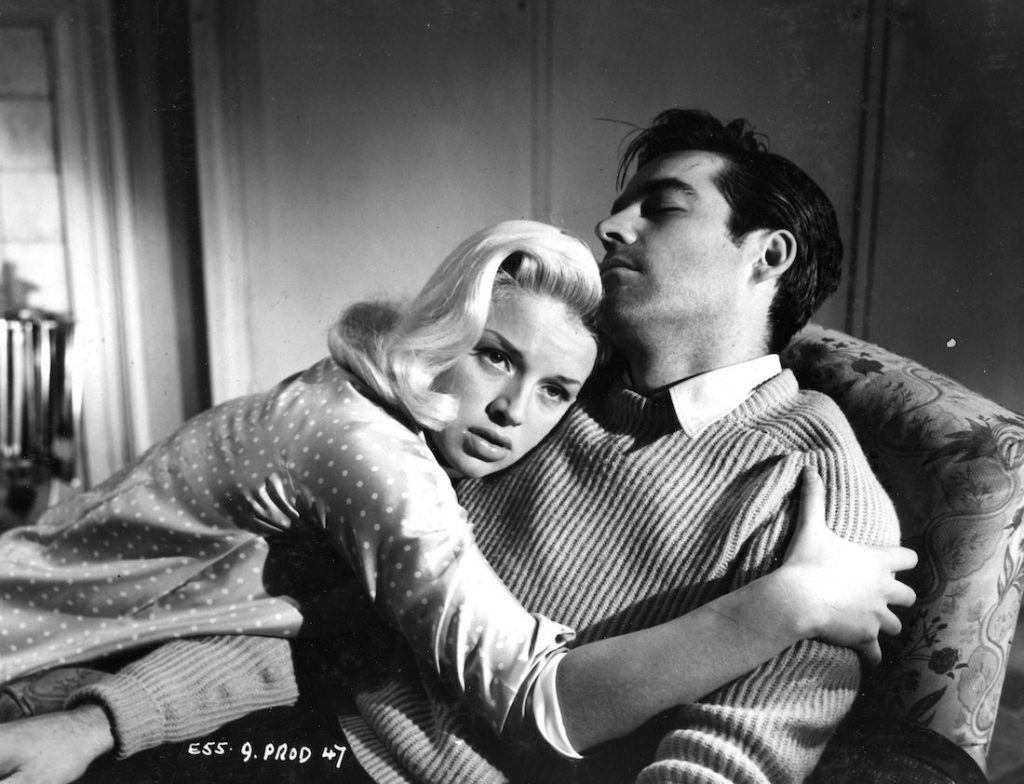

Buy she’s never less than convincing, with so much expressiveness in that face—determined, resentful, sad beneath, occasionally amused—and she absolutely dominates Yield to the Night in the role of Mary, a young shop assistant in 1950s London who’s murdered “the other woman” and, as a result, will soon be hanged. The film intertwines two storylines: Mary’s life leading up to the murder, in particular her infatuation with the irresponsible musician-gambler Jim (Michael Craig), and her last weeks in prison awaiting execution.

We’re in no doubt as to her guilt: the murder comes at the beginning of Yield to the Night and we don’t even see Dors’s face until after she’s fired the gun. We aren’t given any opportunity to know her as anything other than a killer. This contrasts with the other movie of the period dealing explicitly with the experience of a woman awaiting execution, I Want to Live! (1958), a Hollywood product directed by Robert Wise. There, the possibility that Susan Hayward’s character was innocent all along was left open.

But in Yield to the Night, closing off that easy route to audience empathy was a deliberate decision by director J. Lee Thompson and co-writers John Cresswell and Joan Henry (on whose 1954 novel it was based, and who was briefly married to Thompson after Yield). As Thompson said, to make the case against capital punishment most powerful, “you must take somebody who deserves to die, and then feel sorry for them and say ‘this is wrong’. We did that in Yield to the Night: we made it a ruthless, premeditated murder.”

The crime, in any case, isn’t the point of the film (which was crudely and inappropriately re-titled Blonde Sinner for the US market). The point was to give audiences an unsparing view of the punishment that often followed the crime, at a time when hanging was the mandatory sentence for murder in the UK. (Although many sentenced to die were reprieved by the government and served a jail sentence instead; the anticipation of a reprieve is a major source of tension in Yield to the Night.) And the fierce passion of the film, rightly characterised by Melanie Williams in an interview on this disc as a protest movie, has to be seen in the context of the 1950s public debate on the death penalty.

Opposition to capital punishment had been growing in the UK for years, although it was largely miscarriages of justice rather than the practice itself which created public doubt; notable among these, and fresh in minds at the time Thompson’s film was released, were the cases of Timothy Evans (a probably innocent man hanged for killing his daughter) in 1950, and Derek Bentley in 1953 (who may have been trying to prevent rather than encourage a murder carried out by a fellow burglar, but nevertheless went to the gallows).

Audiences, and doubtless the film’s producers, would also have been very aware of the case of Ruth Ellis, the last woman to be executed in Britain, who had been hanged in July 1955—just a few months before shooting began on Yield to the Night. But although the film is often said to be based on her case, Henry had written the source novel before Ellis even committed her crime, and the resemblances of Ellis’s story to the fictional Mary’s are only superficial.

Shortly after Yield to the Night’s release, abolitionists would achieve some success with the passage of the Homicide Act 1957, which restricted the death penalty to certain kinds of murder. (Executions then ended altogether in the mid-1960s.) But at the time the film came out, it was a contentious and unresolved issue.

It’s no wonder, then, that some of the movie’s points about penal reform can seem to be stated a little blatantly, rather than woven naturally into the plot. Yet even so, it still feels like it’s arguing an important case; it feels current and relevant, not historical.

Much of this is down to the acute sense of atmosphere created by Thompson (who went on to make still-remembered movies like Ice Cold in Alex, The Guns of Navarone, two Planet of the Apes sequels, and the 1962 Cape Fear) and abetted by Gilbert Taylor’s photography as well as the fine cast. In many ways it is not a typical prison film—we never meet any other prisoners, for example—but in others it’s a classic of the genre, capturing the deadening routine of life in the condemned cell. Yield to the Night is punctuated by visits from the doctor, the lawyer, the chaplain; changes of shift for the warders; games of chess and solitaire; the daily cigarette ration. Through all this, the bright light of the cell is never, ever turned out.

None of the people guarding and caring for Mary are monsters; they don’t enjoy this job and do their best to comfort her (“the things that we most fear are seldom as terrible as we expect”, promises the doctor; “have you ever thought… we all of us die some morning”, says a warder). But in the face of her own death’s inevitability, these well-meaning attempts seem as futile as their concern over whether her shoes are pinching. Mary is told not be afraid, but as she observes, “how can I be anything else?”

Despite all this, Yield to the Night is far from being an overtly manipulative tear-jerker. The prison scenes are matter-of-fact, characterised by silences and brief, brusque dialogue, contrasted occasionally with the much more emotional tone of Mary’s interior monologue, which adds a kind of naive poetry. There’s literal poetry too, as she quotes A.E. Housman’s A Shropshire Lad (a work which itself refers often to young death, and even to hanging), although the film’s title comes from Homer’s Iliad. And there’s just a hint of a religious overtone: Mary is to be executed in April, the month of Easter.

Alongside the prison storyline, the many flashback sequences pale in comparison, and although a few are successful (notably the almost dreamlike scene in a park where Mary decides to kill Lucy), the film might well have been an even better one without them. The love triangle isn’t especially credible, the scenes between Mary and Jim stray into melodrama, and Dors seems tempted to overact in them too, something that she doesn’t do in the prison sections.

If they have a saving grace it is Taylor’s cinematography, often as striking outside the prison walls as within. The visual style of Yield to the Night is noirish but also very precise, small details often seeming huge, unusual objects frequently foregrounded, and tilted (“dutch”) angles underscoring the awful way in which Mary’s life has unexpectedly developed. It’s as much down to the photography as the acting, in fact, that Mary’s last full day in prison and the few moments we see of her final morning are so hypnotic.

This can give Yield to the Night’s prison scenes a somewhat detached feel, but it’s far from a cold movie, and the passionless bureaucratic aspects of Mary’s days in the condemned cell are counterbalanced by a surprising and tender friendship that slowly develops between her and the warder MacFarlane (Yvonne Mitchell, who received second billing). Mitchell is outstanding, developing MacFarlane into a believable personality with a voice of her own (“can’t you think of anyone but yourself, even now?” she exasperatedly demands of Mary at one point), yet never overshadowing Dors.

All the other warders are full of character too (Mary says “you’re none of you human” but they most certainly are), while colourful minor parts include the prison visitor Miss Bligh (Athene Seyler), sharp beneath her slightly dotty jolliness, and Mary’s scared, confused mother (Dandy Nichols). Among the few male players, Michael Ripper is memorable as Roy, an annoying and lecherous pre-murder friend of Mary’s who laughs at his own jokes (and for all his chumminess never seems to visit her in prison). Michael Craig’s Jim, unfortunately, is rather wooden—although, to be fair to the actor, the character isn’t exactly emotionally open or honest, either.

Ultimately, though, Yield to the Night is all about Diana Dors. The other characters, while the film acknowledges that their perspectives are also important, are to some extent foils for her; and the direction and cinematography, while attention-grabbing in their own right, serve largely to focus our attention on the terrific central performance. Despite the comparative weakness of the flashback scenes, then, it remains an outstanding example of 1950s British cinema—justly nominated for the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

UK | 1956 | 99 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

The 4K restoration from StudioCanal, scanned using the original camera negative, is superb. One couldn’t wish for a better copy of the movie.

director: J. Lee Thompson.

writers: John Cresswell & Joan Henry.

starring: Diana Dors, Yvonne Mitchell, Michael Craig, Marie Ney, Geoffrey Keen, Liam Redmond, Olga Lindo, Joan Miller, Marjorie Rhodes, Molly Urquhart & Mary Mackenzie.