PENNY DREADFUL – Season Three

At the end of season 2, we left the world of Penny Dreadful in flux. The relationships established between its major characters were dissolved. In the finale, “And They Were Enemies”, Vanessa Ives (Eva Green) was left to deal with the consequences of her loss of faith, as each of her protectors left her behind in an empty mansion.

Werewolf Ethan Chandler (Josh Hartnett) was extradited to America by Inspector Bartholomew Rusk (Douglas Hodges), while Sir Malcolm Murray (Timothy Dalton) set off on another fruitless expedition to Zanzibar. Meanwhile, Victor Frankenstein (Harry Treadaway) found dire consolation in drug addiction after his monstrous creation Lily (Billie Piper) decided to create a revolution with immortal Dorian Gray (Reeve Carney) at her side. Only Frankenstein’s other creation, John Clare (Rory Kinnear), could offer Vanessa some hope about finding her way back to the light before he himself retreated into an icy wasteland. Where would the series go from here, with all of its characters dispersed across the globe?

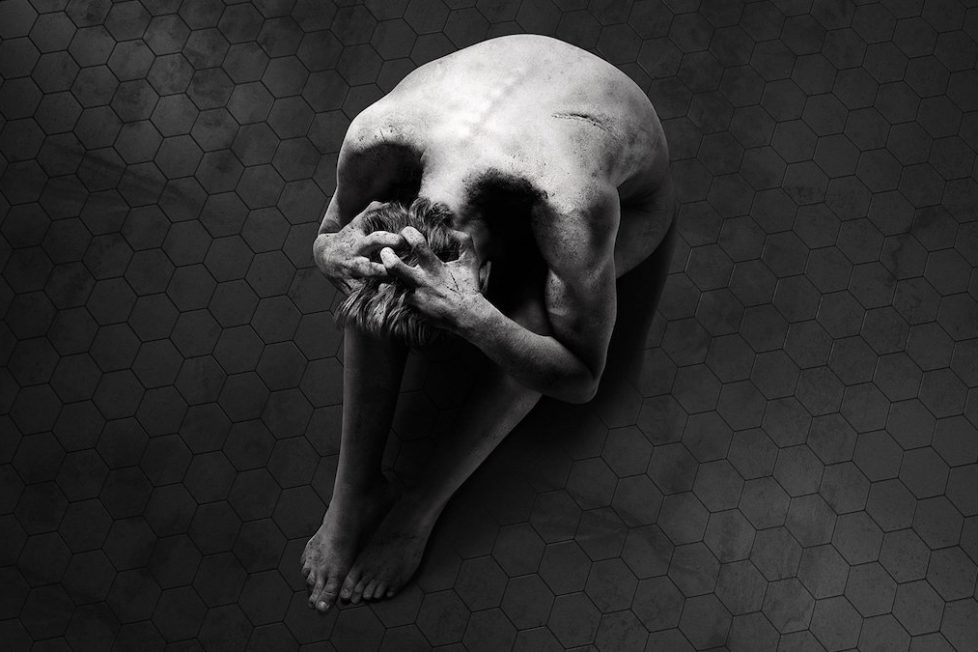

Penny Dreadful’s opening season 3 episode, “The Day Tennyson Died”, wastes no time in providing viewers with the overall structure for what would turn out to be its final year. This decision was not revealed until just shortly before the two-part finale, and certainly there remain some mixed feelings about how creator John Logan chose to drive the story to its conclusion. Primarily, it becomes an odyssey exploring and confirming the authentic nature these characters adopt as they set out to repair themselves psychologically.

The opening episode, alluding to that day in October 1892 when the most popular poet of the Victorian era succumbed to flu, is essentially a rain check on each character’s notion of faith and destiny. While Sir Malcolm, Ethan and John Clare have each moved out into the world, Frankenstein, Lily and, most significantly, Vanessa, have withdrawn to undertake an internal self-reckoning. Mirroring Tennyson’s own death and many themes about faith in his work, Vanessa has discarded her beliefs. Only by the end of the episode does she find purpose again after her friend Ferdinand Lyle (Simon Russell Beale), a delightful character who appears only briefly this year and then never returns, advises her to consult therapist Dr. Seward (Patti LuPone).

Seward is briefly identified as a descendant of Joan Clayton, the witch known as the ‘Cut Wife’ who trained Vanessa in the dark arts and whom we met in last season’s “The Nightcomers”, and thus the series seeks to trace evil not as a supernatural phenomenon but as an affliction that can be cured. This, in turn, inspires a fateful encounter with Dr. Alexander Sweet (Christian Camargo) at the Natural History Museum where, significantly, the series expands its exploration of nature and evil, bestial instinct and human rationality. As if addressing all of our characters’ flaws, in a wonderful scene with Vanessa, Sweet summarises Penny Dreadful’s mission statement: “All the broken and shunned creatures. Someone’s got to care for them. Who will it be, if not us?”

These themes are taken up with another riff on that other Victorian motif—the way medicine and science define rationality and madness—in the relationship between patient Vanessa and therapist Seward, and in the introduction of Henry Jekyll (Shazad Latif), who demonstrates his methodologies to Victor by temporarily curing a schizophrenic inmate of Bedlam. Victor’s obsession with Lily becomes, rather disturbingly, that other object of Victorian patriarchy; denying women the same privileges as men, containing and punishing their aspirations for suffrage.

The prevailing motifs of colonialism and the ‘sins of the fathers’ re-emerge from subplots involving Sir Malcolm and Ethan. Both characters are used to unpick the calamities of British imperialism and the European possession of Native American lands. The show switches back and forth to this subplot, exchanging the palette of Gothic Victoriana for the panoramic deserts of the American frontier.

In an interesting but not entirely successful departure, Gothic horror is swapped for the western genre and the origin of Ethan’s werewolf nature is tied into the Native American traditions of shamanism, skinwalkers, and shapeshifters, rather than any European antecedents. Thrown into this mix, in a rather haphazard way, is the witch Hecate (Sarah Greene) who survived her mother Evelyn Poole’s machinations in last season’s finale.

The father, a major symbol in Penny Dreadful, is also the troubling shadow that hangs over John Clare, the disenfranchised Frankenstein offspring whose sojourn to the Arctic wastes (straight out of Mary Shelley’s conclusion to her original novel) finds him on a deserted ship. Most of the crew have died and the rest have turned cannibal to stay alive. A dying child comforted by the humane John Clare triggers flashbacks to his life before Frankenstein brought him back from death. He sets out to uncover the truth behind the memories and find the family he left behind. It’s a clever idea that opens up the monster’s story and provides Rory Kinnear with some of the most tragic and heartfelt moments in the entire series.

Most crucially of all, the end of the opening episode practically shouts from the rooftops that the antagonist Vanessa faces this season is none other than Dracula, when Seward’s secretary Renfield (Samuel Barnett)—another dead giveaway we’re retracing Bram Stoker’s narrative and characters—falls under his spell as the lord of all vampires forms his plans to seduce her.

In “Predators Far and Near” we also see realised Lily and Dorian’s pledge to exact revenge on mortal society. Except it’s not exactly what Dorian envisaged as the new addition to their cause, the sexually abused Justine (perhaps a nod to De Sade there from John Logan), becomes the lynchpin for a feminist revolution. Justine’s recruitment is a further development of the show’s themes about female agency arising from the damage inflicted upon them by a patriarchal society and the transformation of women into individuals who attempt to control their own destiny.

Over in America, we learn that Ethan is an honorary Apache and Kaetenay (Wes Studi), an Apache elder, has joined Sir Malcolm to rescue Ethan from the clutches of his biological father Jared Talbot (Brian Cox) and Inspector Rusk (Douglas Hodge), who has pursued Ethan doggedly for the werewolf atrocities perpetrated in London. Again, the episode reinforces the failings between fathers and sons and the colonial traumas inflicted on indigenous communities. The sins of the past continue to force their way to the surface while Ethan has to reckon with a triumvirate of guilty father figures.

By the episode’s conclusion, it’s revealed that Renfield’s unseen master is none other than Dr. Alexander Sweet, the smooth talking taxidermist zoologist in whose company Vanessa has finally found a modicum of comfort and love. However, one of the problems made apparent by the third episode, “Good and Evil Braided Be”, is that the constant jumping from one subplot to another does not entirely benefit the storytelling.

It takes a long time to bring all of the characters back together to combat Dracula. This isn’t fully realized until the two-part finale, and before then we shift restlessly between the various locations to play out separate character developments and scenarios. It all feels like there are too many separate stories vying for our attention, and that there isn’t a big enough central story to eventually knit these into.

“Good and Evil Braided Be” focuses on Ethan’s backstory. When Hecate views him as an apocalyptic force she can join forces with, his destiny as the ‘Wolf of God’ comes to the fore. Vanessa and Seward continue to deconstruct Vanessa’s belief that evil is personified in monsters. Seward attempts to rationalise her vampires and werewolves as a psychosis, the mind trying to create order from her mental illness. But Vanessa knows she is being stalked by something very evil indeed. With Seward’s character as a foil to Vanessa’s, Penny Dreadful explores the duality between rationalism and the supernatural, the body and the mind. It achieves this supremely with the episode’s cliffhanger as Seward regresses Vanessa to her treatment in the asylum of season one’s “Closer Than Sisters”. That her warder is none other than John Clare, prior to his death and resurrection by Frankenstein, is an intriguing development.

Lily’s assertion to create an army of fallen women to exact revenge on male society becomes an extreme form of suffrage and, as we see later, it is one that Dorian gradually finds unpalatable. In other developments, the relationship between Jekyll and Frankenstein unpicks some of the class and race differences within this society. Jekyll’s anger and Frankenstein’s isolation are further iterations of the monstrous as a crisis of identity, of the foreign as a mark of the perverse. Both men are looking for ways to return to society, to reclaim their status through science. Most importantly, Frankenstein seeks to reverse his male inferiority by curtailing Lily’s development as an autonomous liberated female force.

The aforementioned cliffhanger of John Clare’s attendance on Vanessa in her cell leads into the two-hander with Eva Green and Rory Kinnear in “A Blade of Grass”. Seward delves into Vanessa’s mind to try and pinpoint when she first met Dracula, the master vampire now stalking her. This is quite an intense exploration of Vanessa’s ‘madness’ and, although it isn’t entirely clear, there’s a suggestion that this isn’t just John Clare but merely some prior manifestation of Dracula using his appearance to exploit Vanessa’s self-doubt.

Certainly, we’re left unsure if this was John Clare. In “Ebb Tide” he has no recollection of ever working as an orderly when Vanessa relates this to him. More importantly, despite John’s recollection of his past life, we never learn how he died and fell into the clutches of Frankenstein. For a final season, it’s this lack of closure that becomes very frustrating. That said “A Blade of Grass” brilliantly showcases the skills of Green and Kinnear who, for me, are the backbone of Penny Dreadful.

In “This World is Our Hell” Ethan’s repression of his true Apache nature is driven by the vengeful father figure of Jared Talbot and his desire to punish Ethan for sins previously committed. The unfurling of the true self is the core of the series, and while Hecate wins over Ethan’s bestial nature to the cause of monstrous liberation, Jekyll and Hyde desire to repress those forces that brew within them; be they Jekyll’s anger, Frankenstein’s unrequited love or Lily’s radical version of suffrage.

Taking the Gothic into the Western genre seems to reflect the times well, a period when those great symbols of Victorian literature Dickens (in 1842 and 1867) and Wilde (his 1882 lectures took him from East to West including Colorado and Texas) were touring America. Wilde certainly had a perspective on the frontier’s symbolism and its distinction between civilisation and barbarism that Penny Dreadful evokes here. Ethan must decide if he is on the side of untamed evil or redemptive good, whether he follows his adopted fathers or capitulates to Hecate’s vision of the great evil that overtook the Apaches. There’s a spectacularly violent answer to this question in “No Beast So Fierce” but killing off Inspector Rusk, Ethan’s father, Hecate and numerous ranch hands puts a full stop to this particular subplot. Logan sloughs off characters rather too easily, leaving a number of plot strands in mid-air with no real conclusions.

“No Beast So Fierce” also signals that perhaps a similar fate awaits Dorian and Lily’s blood-spattered ingénue Justine (Jessica Barden), as Lily’s revenge on Victorian middle-class gentlemen takes the form of a gang of trained female assassins culled from the most disenfranchised of women in society. As the unruly gang of prostitutes take it onto the streets and pile up the bodies, Dorian starts to ponder his own survival. The overthrow of patriarchal London society begins to falter when Lily is kidnapped by Victor, prior to his attempt to pacify her with the injections he has developed with Jekyll’s help.

John Clare finds his family. It’s a truly heartbreaking moment when his son initially rejects him. The idea of the monster eavesdropping on a family is again another striking scene straight out of Shelley’s book. Vanessa finds female companionship in Catriona Hartdegen (Perdita Weeks), a thanatologist and expert in supernatural lore. Frustratingly, Catriona is a promising character introduced far too late into the proceedings and we get little of her development or backstory. She provides the necessary intelligence about Dracula and offers Vanessa an enlightened perspective in her modernist approach to the place of women in society. Some fans even theorised that Catriona was from the future and an iteration of the time traveller from H.G. Welles’ The Time Machine. Like the possibility that Ferdinand Lyle’s trip to Egypt was a link to the next season’s potential face-off against ancient mummies, her origin story is unfulfilled as Logan continued to shut down characters and narrative to get to his flashy but somewhat disappointing finale.

“Ebb Tide” sees John Clare’s reunion with Vanessa, who does remember him from her incarceration and encourages him to return to his roots and find acceptance again with his family. Just as she tries to emerge into the light, she dares him to “join the dance” and hope that all “the lost souls be found.” Kinnear and Green are totally captivating in this brief scene. When John Clare finally plucks up the courage to speak to his wife Majorie (Pandora Colin), he finds an astonishing welcome from her: “You were lost. And now you are home, husband.” Even their son Jack, now fading fast from consumption, finds the courage to accept the return of his father. Alas, it is a short-lived fatherhood for John Clare.

That Dracula rules over “the house of the night creatures”, as Catriona puts it, is the final clue that sets Vanessa on a collision course with Alexander Sweet at the museum. And so with Dracula and Vanessa meeting on their own terms, it’s interesting to note that it is Vanessa who has been handed the power to rule as “the mother of darkness”. As Dracula convinces her, she should abandon her constructed self—one that “your church and your family and your doctors said you must be”—and become her authentic self. From this scene onward Logan dooms Vanessa to her fate and the woman who trained to be a powerful witch, saw off demons and understood that it was a strength to be different completely evaporates from the narrative.

And so to the finale, “Perpetual Night” and “The Blessed Dark”. Dorian, bored to tears by Lily’s disinterest in him and his receding influence on Justine and the army of deviant women, turns Lily over to Victor Frankenstein, hoping that his friend will “make you into a proper woman”. It’s a very ghoulish perspective on the role of womanhood in Victorian society and how white male privilege was determined to maintain their servitude within the home and keep them away from the public sphere as much as possible. Lily’s rage at this treatment is understandable after we were given a fresh perspective on her history as a single parent, in her former guise as Brona Croft, with her visit to the graveyard at the start of “Ebb Tide”.

What doesn’t quite work is Victor Frankenstein’s abrupt change of heart in freeing Lily. Lily’s impassioned speech is effective but, as storylines and characters jostle for resolution in the finale, this development seemed too hasty to ring true. Dorian removes the rebellious Justine, another underused character, from the equation and cancels the revolution, throwing his guests back out onto the street. He has a salient warning for all would-be immortals, including Lily, “All age and die, save you. All rot and fall to dust, save you.”

After Lily bids farewell to Dorian and she is left to her immortal fate, that is pretty much it for both Billie Piper and Reeve Carney in the series. They dissolve back into the Victorian fog along with Shazad Latif’s renamed Lord Hyde. Meanwhile, Ethan, Sir Malcolm, and Kaetenay are, of course, on their way to England after an Apache vision warns them of Vanessa’s plight. Teaming up with Seward, who hypnotically regresses Renfield to pinpoint Dracula’s location, they storm the vampire’s lair with Victor’s and Catriona’s help.

Yet, it is Rory Kinnear who again steals the show for me. The reconciliation of John Clare’s family is short lived. His son Jack finally succumbs to his prolonged illness and the dreams of games in the park and seaside holidays wither and die with him. A distraught Marjorie entreats John to take Jack’s body and bring it back to life with Frankenstein’s help. Or never come home again. The scene of John Clare putting his son’s swathed body into the sea says so much about the monster’s humanity. He simply didn’t want to bring another monster, another outcast freak into the world and accepted loneliness as his reward.

It’s also a finale that barely features Vanessa, the central character around whom practically everything else revolves. Her brief appearances are saved up for the ‘love redeems all’ ending where her self-sacrifice is apparently the only way to avert the apocalypse. As closure for the show, it felt sparse, unearned, and Ethan’s destiny to shoot her also denied Vanessa a satisfying redemption. Are we to believe that in her abrupt martyrdom she finally reclaims her faith and keeps her feminist principles intact? We didn’t even get a valedictory blood and thunder ending for Dracula. He just vanishes into the night along with the other characters whose manifestations of patriarchy and female empowerment were unsatisfactorily interrogated.

When that lonely caption ‘The End’ appears on screen it doesn’t feel as complete as it deserved to. There are too many unanswered questions and unresolved fates. It seems Vanessa’s grave was the only destiny that Logan had for her after three years mapping out her constant struggle to be herself. Her kindred spirit, John Clare, provides an epilogue with Wordsworth’s Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood. Ironically, it’s about recalling the euphoric optimism of childhood, which the pain and suffering of adulthood threaten to, but can’t completely destroy. Precious little optimism left in Penny Dreadful by then.