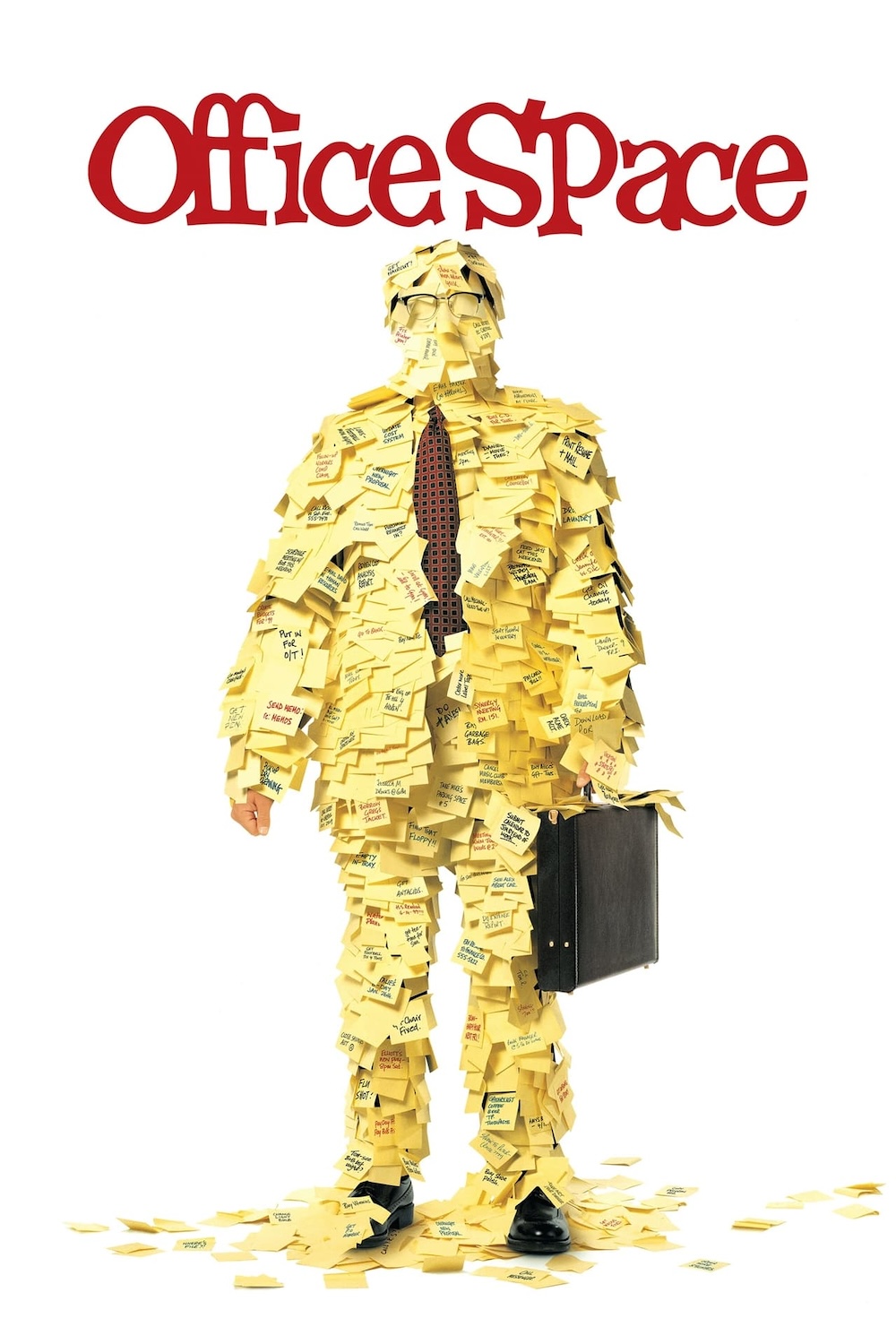

OFFICE SPACE (1999)

Three company workers who hate their jobs decide to rebel against their greedy boss.

Three company workers who hate their jobs decide to rebel against their greedy boss.

Few decades in cinema captured the frustration with consumerist culture and the soul-crushing nature of modern work as effectively as the 1990s. Both Trainspotting (1996) and Fight Club (1999) open with monologues or taglines that confront the viewer, jolting them from complacency: “Is this the life you chose?” they seem to ask. “How did you let it come to this?”

This direct challenge to audiences, demanding that they explain their existence to themselves and others, can also be found in Office Space. However, the approach is subtler. While those other films share a clear interest in exploring the dehumanising effects of the 20th-century workplace, Office Space is decidedly funnier than its contemporaries. Falling Down (1993) opens with a disgruntled man experiencing an existential crisis in Los Angeles traffic, while Office Space features an identical opening, albeit with a vastly different tone. Instead of lamenting William Foster’s (Michael Douglas) sorry circumstances, we are invited to laugh at Peter’s (Ron Livingston) miserable attempt at driving to work—and perhaps even at ourselves.

Peter hates his job, with a fervour unmatched by anyone else at his office. Every day is the worst day of his life. So crushed is he by the tedium of his menial tasks and the watchful eyes of his eight supervisors that he fantasises about going on a rampage. Craving an escape from his workaholic nightmare, he envisions an occupational hypnotherapist transforming him into a mindless drone and model employee at Initech, a giant software company. However, a bizarre twist during his therapy session results in an unforeseen outcome: Peter achieves a state of profound serenity. Worldly concerns like his job, his bills, and even his girlfriend dissolve into insignificance, lost in a cloud of blissful detachment. Though he has transcended earthly anxieties, his spiritual path now led him to destinations he never could have foreseen…

Office Space, released in February 1999, initially went relatively unnoticed. Despite its $10M budget, it only secured a meagre $12M at the box office, deeming it a box office bomb. Nevertheless, writer and director Mike Judge (Beavis & Butthead) crafted a film with timeless and universal appeal, making it equally enjoyable and relevant today as it was upon its release. Office Space transformed into an ode to the overworked and underappreciated individuals trapped in cubicles or any loathed job. Satirising the apathy within corporations and the alienating effects of technological advancements, this comedy offers more than just laughs; it has real substance beneath its humour.

The opening of Office Space immediately strikes you with its distinctly independent 1990s feel, a texture long expunged from modern comedies. Movies like Dazed and Confused (1993), Clerks (1994), Kicking and Screaming (1995), and Bottle Rocket (1996) all have it in spades. Traces of this style persist in the work of independent filmmakers who rose during this era, such as Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach. However, both these auteurs seem to have finally abandoned this aesthetic, drawn to bigger productions as evidenced by their most recent films, Asteroid City (2023) and White Noise (2022), respectively.

There is a laidback, offbeat vibe to these nineties comedies. They feel charmingly lackadaisical, moving at an organic pace with a deliberate naturalism that is sadly absent in many contemporary offerings. In contrast to their reality-exaggerating counterparts, films like Office Space lampoon our daily situations with an almost documentary-like accuracy. Take, for instance, the infuriatingly relatable example of Peter watching the painfully slow download progress bar when saving a file. That simple image effectively captures the feeling of being held hostage by our technology, the metaphor perfectly illustrating how deeply intertwined our lives are with these big, white boxes of wires and plastic.

This preoccupation with how the human condition is quietly eroded by our reliance on technology informs most of the comedy in Office Space. In one poignant moment, Peter experiences a terrifying dream where a judge, gavel in hand, turns to him and intones: “Peter, you’ve led a trite and meaningless existence.” The unshakeable sensation that he’s wasting his life induces a panic in him, a deeply rooted ennui that catalyses much of the plot. As he sits helplessly in traffic, watching an old man hobble away on his Zimmer frame, one is reminded of a quote from Fight Club: “This is your life and it is ending one minute at a time.”

Besides his close friends, few at Peter’s office seem to outwardly share his existential torment. Those around him mock him for his perpetual case of “the Mondays,” implying that deviating from the workaholic lifestyle invites criticism. Thus, Peter’s longing for tranquillity in a world characterised by production anxiety sets him apart from most of his co-workers. He refuses to fit into the soulless, mindless drudgery of his nine-to-five existence, an idea hinted at by the corporate artwork outside Initech’s headquarters—a square peg in a round hole.

Peter’s desperate desire to flee the dehumanising monotony of corporate life pervades the film. Throughout it, we see subtle musings on escaping such a fate. One suggestion is the pet rock, a concept Tom Smykowski (Richard Riehle) dryly suggests requires only a million-dollar idea to end the depressing slog permanently. Whether the pet rock was cleverly foolish or foolishly clever, it exploited the mindless, impulsive consumerism people use to justify their soul-crushing jobs. Mike Judge ironically positions objects of consumption as the solution to a life dominated by the cycle of production and consumption, framing hopeful characters in a rather merciless light.

Of course, other characters find different forms of escapism. For Michael Bolton (David Herman), it’s his rap music, which he blares from his car stereo. This genre choice seems too specific to be a mere coincidence. After all, rap originated as an art form to give voice to the repressed. The persecuted masses utilised angry, evocative lyrics to fight against the status quo, to lambast the establishment that kept them down. In this way, we can see how characters like Bolton outsource the rebellion that they cannot foster in themselves.

After all, there is no place for such defiance in the office. It is a boring place where Hawaiian Shirt Day represents the extremes of wild behaviour. Even oppression has lost its bite here, a dull thrum of authoritarianism that numbs rather than terrifies. There are no disturbing devices as shown in the denouement of Brazil (1985). Instead, it’s as painfully simple as monotone boss Bill Lumbergh (Gary Cole) telling Peter he has to work over the weekend. It’s clear Lumbergh relishes his position of power, as well as his abuse of subordinates. Vindictiveness and self-satisfaction are the only emotional states he demonstrates.

Mike Judge, having (likely) endured such agonising bureaucracy himself, wields a ruthless pen in his criticism of these corporate sadists in suits. His disgust with corporate greed permeates the screen, leaving no room for doubt. This disdain finds expression in his portrayal of the emotionless, unfeeling business consultants—mere clones, identified only as Bob and Bob.

While Judge expertly conveys his frustration with office tyranny and the alienating effects of modern work, he lacks concrete solutions to the crisis he deplores. When Peter begins to ditch work, he returns to the wild, sighing satisfactorily as he holds a freshly caught fish. Perhaps, as he guts his salmon and dumps the innards onto a pile of unanswered TPS reports, Judge is suggesting that a return to a more natural way of living is the way forward. Admittedly, films like Fight Club, Falling Down, and Trainspotting didn’t necessarily have practical answers either; such issues are too big to solve in the context of a 90-minute comedy.

Judge’s pessimistic portrayal of workplace ennui, while not novel, stands out for its comedic brilliance. His inspiration is evident in his use of whimsical dialogue, seemingly replacing the slapstick of Modern Times (1936). To amplify the office’s depressing nature, Judge delves into literary giants. Franz Kafka’s work life was very much like Peter’s, which is partly why the author had such an interest in the dehumanisation inherent within systems. Indeed, Peter’s robotic, inhumane superiors mirror the faceless bureaucracy Josef K. is faced with in The Trial (1925).

An uncanny similarity also exists between Judge’s Office Space and the work of George Orwell. The stark offices in Brazil, inspired by Orwell’s 1949 novel 1984, bear a striking resemblance to the cubicle where Peter spends most of his days. Through this parallel, Judge, Terry Gilliam, and Orwell seem to be commenting on how these confining spaces aren’t expressions of individuality, but rather, cages within a larger totalitarian system. While Judge maintains a light tone throughout the film, Peter’s vitriolic comparisons between his bosses and fascist regimes hint at a deeper, graver message from the director himself.

While the wealth of ideas in Office Space provides ample food for thought, it’s the humour that keeps us returning. Oscillating between dark, absurd, and outright silly, it never fails to ring eerily true. From the portrayal of agonizingly annoying co-workers to the patronizing lectures on soft skills and customer care from superiors, the film hits familiar beats.

Perhaps the pinnacle of Judge’s mordant comedy arrives in the scene where Tom’s bungled suicide attempt leaves him wheelchair-bound and sporting a full-body cast, yet elated after winning a seven-figure settlement. “Good things can happen in this world! I mean, look at me!” he exclaims, the absurdity underscored by his physical state. In Mike Judge’s view, even a devastating collision or a building fire can offer an escape from the soul-crushing world of work.

While the writing and direction are truly superb, the film would have crumbled without the unforgettable performances. Livingston brilliantly conveys both blithe disinterest and heart-breaking despair, never resorting to exaggeration or overacting—a choice that aligns perfectly with the film’s theme of exploring the day-to-day struggles of an ordinary person.

Regrettably, Livingston seems to have been unjustly overlooked by the industry. Never again has he helmed a film like he did here, arguably due to his understated, muted performance. When compared to contemporaries like Adam Sandler, Jim Carrey, Robin Williams, Eddie Murphy, or even Will Smith, his performance stands out for its subtlety, which ultimately strengthens the film.

Gary Cole delivers a pitch-perfect performance as Lumbergh, perfectly embodying “all that is soulless and wrong” in modern corporations. He straddles the line between being genuinely punchable and a remarkably talented actor. In stark contrast, David Herman and Ajay Naidu charm the audience as their characters; we instantly connect with their barely contained rage. Particularly amusing is their disappointment with the surprisingly banal nature of white-collar crime.

Perhaps the most underappreciated performance in the film is that of Peter’s neighbour, Lawrence (Diedrich Bader). Bader portrays him as the virile, deep-voiced foil to our protagonist. Embodying carefree, contented masculinity, his handlebar moustache and fulfilled manner demonstrate that he’s everything Peter is not. Although explored more deeply in Fight Club, the theme of how modern capitalism threatens traditional notions of masculinity is also hinted at here, albeit marginally.

Judge’s film triumphs not just because of its style, humour, or the complex ideas it tackles, but because of how it masterfully weaves all these elements into a cohesive 90-minute comedy. At times, the message takes on the fervour of a frantic plea for action: “Michael, we don’t have a lot of time on this earth! We weren’t meant to spend it this way. Human beings were not meant to sit in little cubicles staring at computer screens all day!” This prescient lament resonates even more deeply today, as this epidemic has become even more ingrained in our cultural subconscious, so much so that escape seems deeply unlikely.

However, at other times, Judge appears content to mock such problems. There’s no need for elaborate misdeeds like fraud, arson, or strychnine-laced guacamole to reclaim control. Sometimes, simply getting outside and breathing fresh air is enough. As Joanna (Jennifer Aniston) aptly tells Peter, “[Most people struggle with their jobs]. But you go out there and you find something that makes you happy.” While simplistic, it’s also rather heart-warming—much like the film itself.

USA | 1999 | 89 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Mike Judge.

writer: Mike Judge (based on ‘Milton’ by Mike Judge).

starring: Ron Livingston, Jennifer Aniston, Stephen Root, Gary Cole, John C. McGinley, David Herman & Ajay Naidu.