THE HOUSE THAT SCREAMED (1969)

A strict headmistress runs a secluded school for wayward girls in 19th-century France, whose students are disappearing under mysterious circumstances.

A strict headmistress runs a secluded school for wayward girls in 19th-century France, whose students are disappearing under mysterious circumstances.

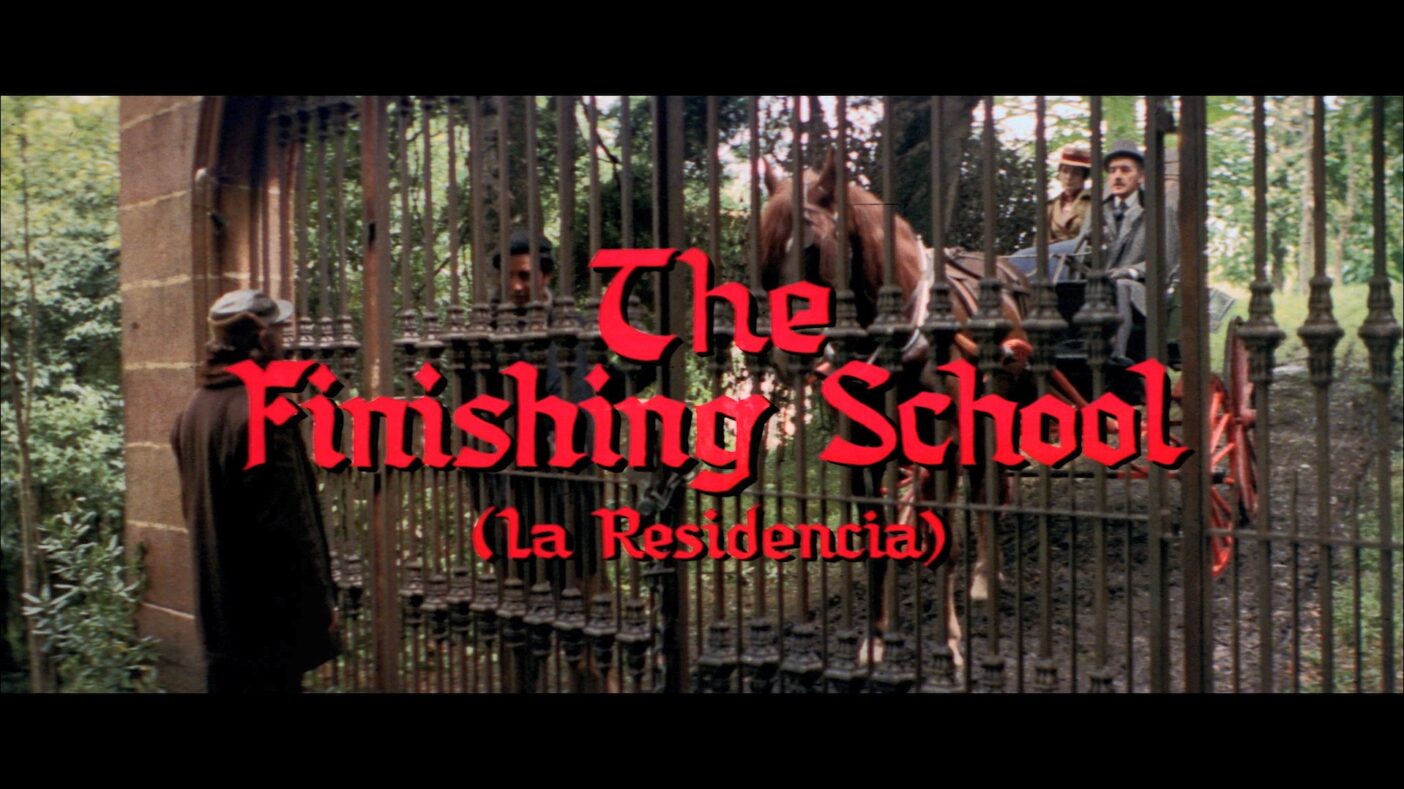

For genre fans, this sympathetically restored print of Narciso Ibáñez Serrador’s psychological horror La Residencia / The Finishing School, making its UK Blu-ray debut, is a most exciting recent release from Arrow Video. Along with generous bonus material, there’s the choice of two versions: the original uncensored Director’s Cut and the trimmed-down version distributed internationally under its English-language title of The House that Screamed.

It may be the most important horror film to come out of Spain and it’s certainly one of the most influential, if only by way of Dario Argento’s Suspiria (1977). In many ways, they’re very different films, but the stylistic, structural, and thematic similarities are striking: both are set in an isolated, female-dominated environment with a sinister clique at its heart. Argento was impressed by Serrador’s use of colour and mastering of slow-build suspense, admitting The House that Screamed inspired him to use colour as a narrative element in Suspiria and informed his distinctive visual approach to the horror genre ever since. Among their predecessors, both Argento and Serrador cite the Italian horror maestro, Mario Bava as a significant influence… The House that Screamed sits comfortably in a shared lineage with The Whip and the Body (1963) for its sadomasochistic themes, Blood and Black Lace (1964) as a proto-giallo whodunnit, and Kill, Baby… Kill! (1966) for its Gothic atmosphere… and not to mention the big iron gates.

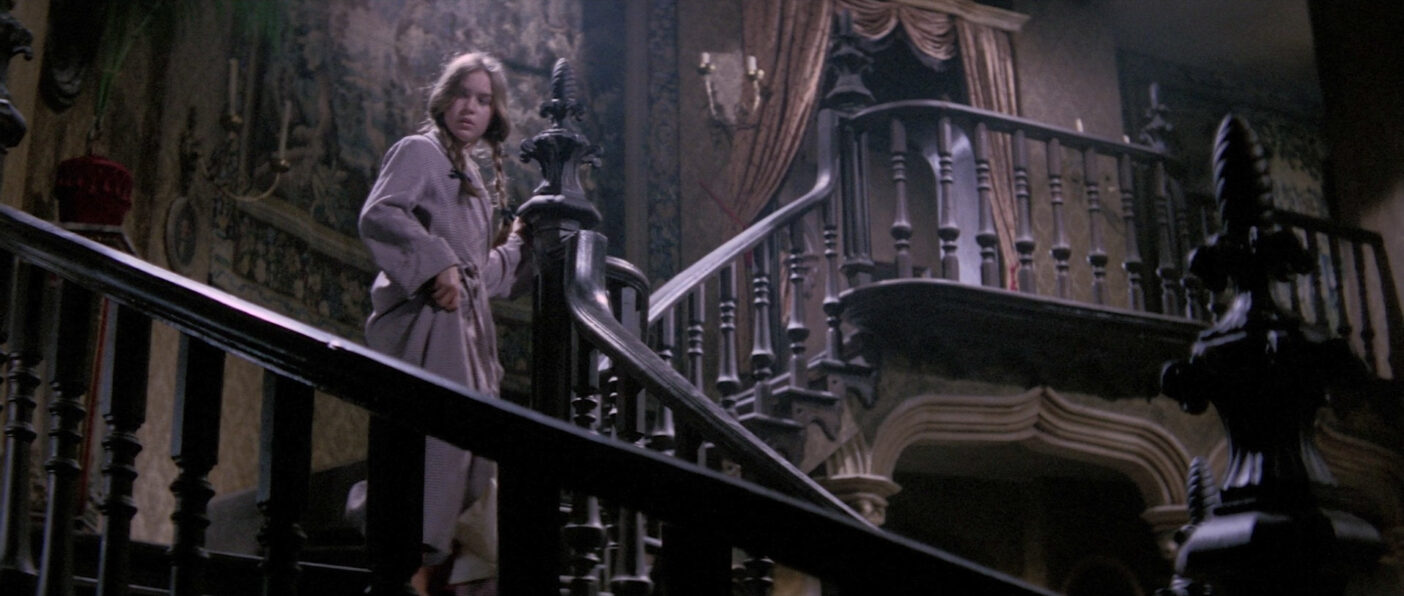

During the opening titles, accompanied by a superb score by Waldo de los Rios, we arrive at those foreboding gates with young Teresa (Cristina Galbó) who’s being deposited at the discrete ‘finishing school’ by an older gentleman (Tomás Blanco) describing himself as a friend of the family to the headmistress, Madame Fourneau (Lilli Palmer). By the way he pays upfront and declines a receipt, it appears he doesn’t want his name associated with the transaction and we guess he just may, secretly, be Teresa’s father.

We’re only minutes in and already every line of dialogue is heavy with implications. We gather that rather than being a finishing school for young ladies, it’s a boarding school for wayward girls whose families want kept out of the way. The setting is 19th-century France, so it wouldn’t take much to be considered ‘wayward’ and Madame Fourneau proudly proclaims that she rules the school with a firm hand. It’s not long before we get a demonstration of just how firm.

During tedious dictation practice, Catalina (Pauline Challoner) dares to stop writing and answer back to Madame Fourneau and is summarily escorted to the punishment room, where Irene (Mary Maude) is deputised by the headmistress to mete out a lashing. The moment when Fourneau hands young Irene the leather whip already has a certain phallic frisson and the ensuing sadomasochistic sequence is disturbingly intense and unmistakably sexualised as Fourneau, Irene and her two constant cronies loom over their seemingly willing victim. This is the triad of power in the school: Madame Fourneau is the dictator though her power, at least in part, relies on the approval of her ‘enforcer’ in Irene, while Catalina threatens to disrupt the dynamic with her rebellious nature but ends up serving as an example of what happens to anyone who tries to think for themselves and question authority.

The versatile veteran actress, Lilli Palmer, had already chalked-up over 60 big screen appearances and was past the mid-point of a career spanning five decades, fresh from playing the Marquis de Sade’s mother, in De Sade (1969). Here, she delivers a wonderfully measured performance that oscillates between chilling, creepy, sadistic, and even allows an occasional glimpse of vulnerability through the chinks of her ice queen stoicism. We only get hints of Madame Fourneau’s backstory but her unblinking stillness is like the centre of a storm within, fuelled by repression and resentment. Perhaps she was once a wayward girl who hardened herself against the iniquity of the male-dominated world beyond the walls of the gothic mansion she now commands.

Lilli Palmer was a German-born actress who started her career on the Berlin stage before fleeing Nazi persecution, by way of Paris to Britain where she transitioned to screen with some 20 appearances—including Alfred Hitchcock’s The Secret Agent (1936) and a starring role in Chamber of Horrors (1940)—before moving to the US after the war and becoming a major Hollywood star.

Although the part of Madame Fourneau had been offered to a couple of Spanish actresses, Serrador made the shrewd decision to appeal to international audiences through casting and shooting most of the film in English and dubbing the Spanish actors, making The House that Screamed the first Spanish production presented in the English language. It was then re-dubbed for the Spanish domestic market. The script is so succinct and well-crafted that I assume some subtleties would be lost through dubbing, but when combined with meticulous performances all round, simple gestures, glances, and body language, its rich subtext should still speak volumes.

Predominantly, the other key players were cast in London including Pauline Challoner and Mary Maude. The latter was originally given a bit-part but stepped into the role of Irene when the original actress backed-out—fortuitous for the production as she gives a bravura performance, peeling away the layers of the increasingly complex Irene and pulling-off a spectacular character turn-around.

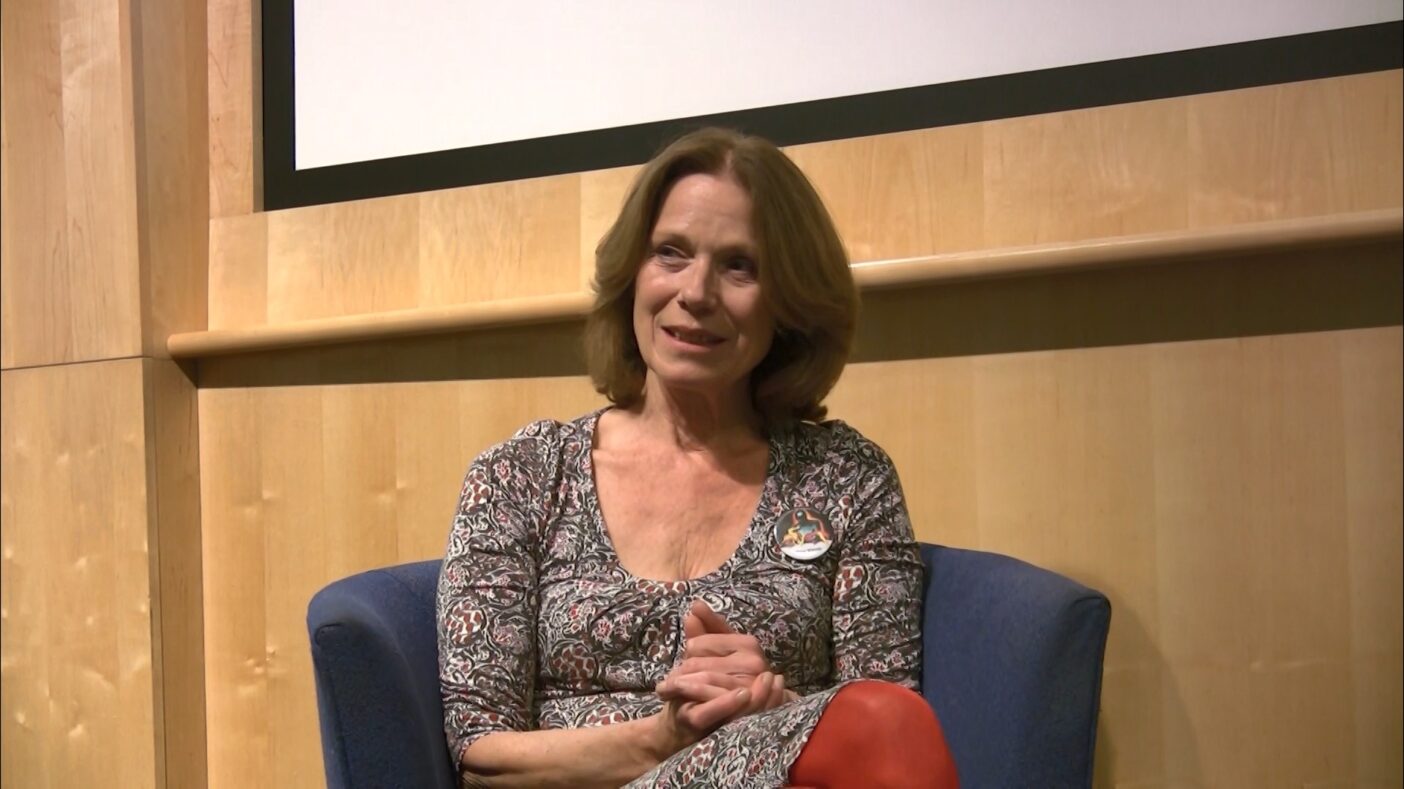

Which brings us to Spanish actress Cristina Galbó, who reveals an underlying strength and determination in the gentle Teresa, ostensibly the protagonist and the catalyst to disrupt the established authority gradients in that triad of feminine power. After The House that Screamed, Cristina Galbó quickly gained a genre fanbase for her appearances in Euro-horror and gialli—notably, Massimo Dallamano’s What Have You Done to Solange (1972)—before quitting the business to become a professional flamenco dancer.

Apart from Lilli Palmer, it seems all the principal players were in the process of transitioning from being child actors to taking young adult roles. The male lead is filled by another English actor John Moulder-Brown, who was just 15 at the time. So, he’s perfectly cast to play the 15-year-old Louis, Madame Fourneau’s mollycoddled son wrestling with his teenage libido in a house full of adolescent girls. His pivotal scenes signpost the recurring themes of awakening sexuality and the subjugation of natural desires as a tool of authoritarian control.

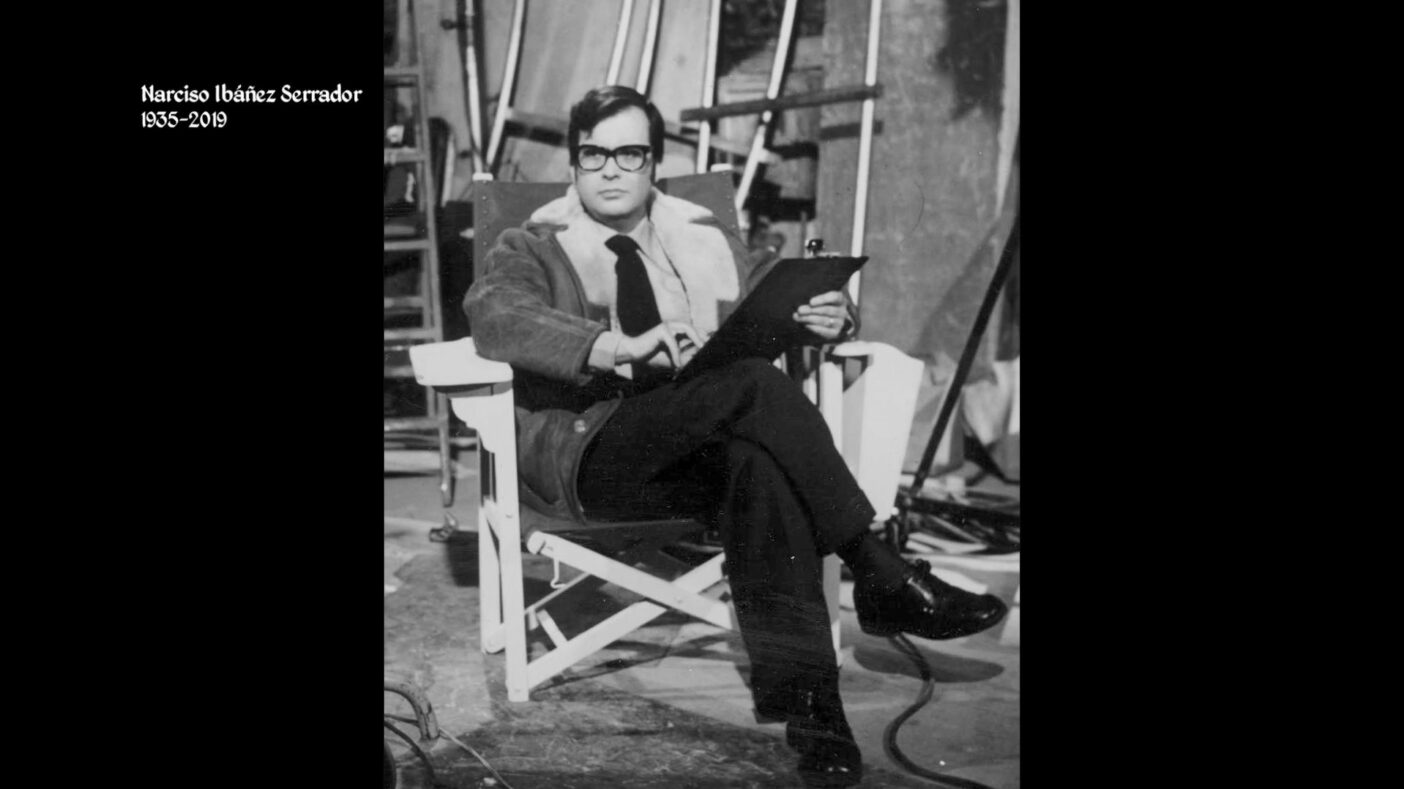

At the time, writer-director Narciso Ibáñez Serrador maintained that the film had no intentional political or social message. Well, he would say that as he was operating during the latter years of Spain’s oppressive Franco regime when any film script had to be scrutinised and approved by the state censors prior to production. Although it seems the censors were a little more lenient in the case of films dealing with mystery and imagination, they would only accept horror if set in another society and, therefore, not directly critical of their own.

However, it doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to read the film as a critique of the political climate in late-1960s Spain with the enclosed school environment serving as a metaphor of the staunchly Catholic nation under Franco’s rule. Perhaps Madame Fourneau’s repressive rules, sublimating sexuality and suppressing self-determination, reflect Francoist authoritarianism, censorship and Catholic control.

Censorship doesn’t seem to have caused too much trouble at the script stage with the only adjustments concerning nudity, particularly during a communal shower scene, which contains two essential plot points. Narciso Ibáñez Serrador circumvented the issue by having the girls wear modesty gowns, which only helped highlight the weaponised Catholic morality and, by contrasting it with the prolonged punishments scenes, made the psychological connections between the two even clearer. They were fine with the whipping, bloody murders, and psychological torture, but don’t expect too much skin—it’s not that kind of film, even though some theatrical trailers tried promoting it as such.

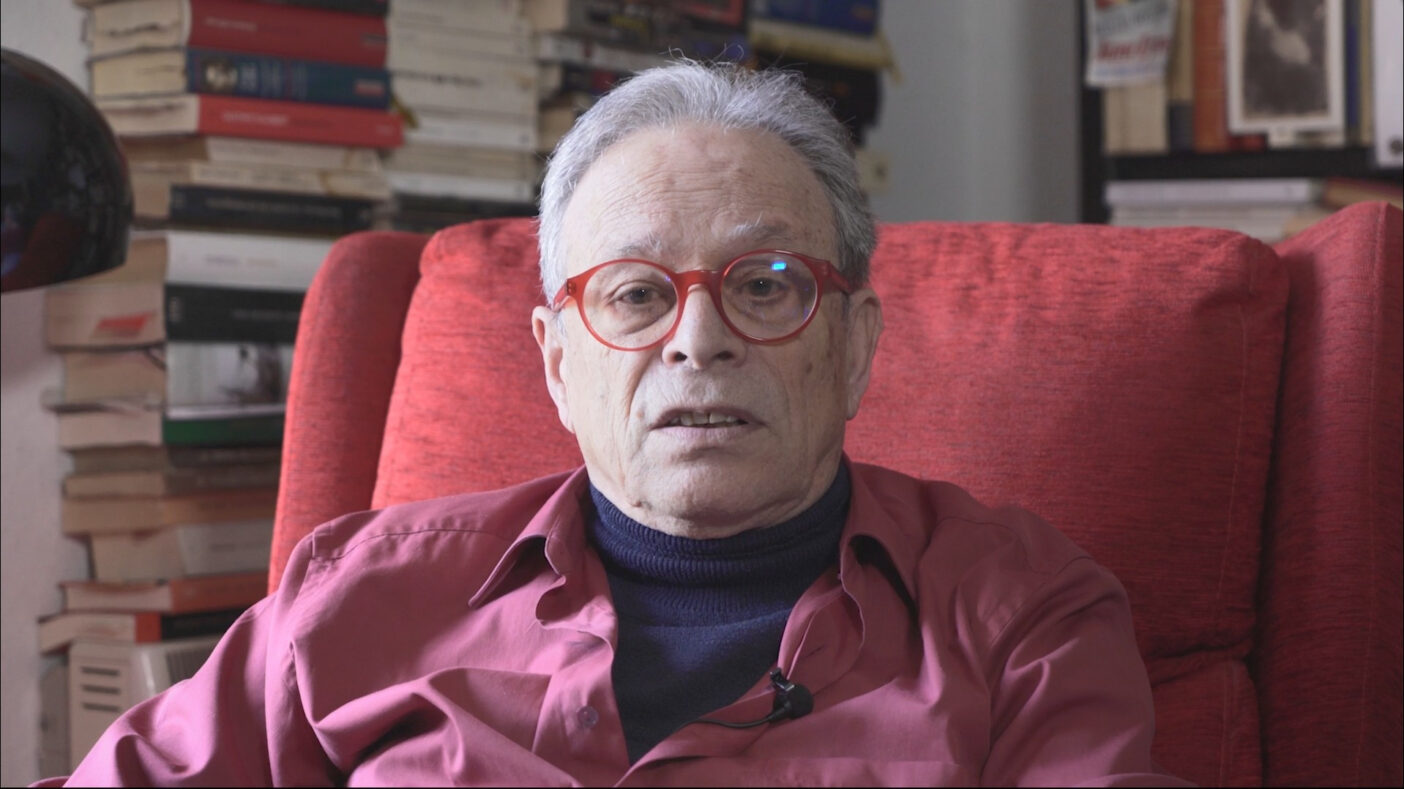

The House that Screamed began as a short story by Juan Tébar who’d worked with Serrador as his assistant director on the television series, El Premio (1968-69) and collaborated on writing some episodes, contributing the script for one. He’d offered his short story, Mamá for inclusion in the Serrador’s seminal horror anthology series Historias para no Dormir / Tales to Keep You Awake (1966-68; 1982) but the director liked the premise so much, he decided to hold it back with the intent of developing it as his feature debut.

By that time, Narciso Ibáñez Serrador, or ‘Chicho’, had become a household name in Spain as synonymous with mystery thrillers as Alfred Hitchcock or Rod Serling. Tales to Keep You Awake was a hit series in the early days of Spanish TV and featured an assortment of original screenplays and adaptations based on classic horror stories by the likes of Edgar Allan Poe, William Wymark Jacobs, Fredric Brown, and Ray Bradbury—notably his Demon with a Glass Hand which had also been adapted as an episode of The Outer Limits (1963-65). The first season of Historias para no Dormir won a Golden Nymph at the Monte-Carlo Television Festival, becoming the first Spanish television production to win an international award. (Serrador would reprise the series in 1982, and a modern reboot, Stories to Stay Awake, premiered on Amazon Prime Video in 2021, now streaming on Apple TV.)

Building on this success, he created Spain’s first independent film production company, with producer Arturo Marcos, and eventually managed to secure a respectable budget. He developed an original screenplay, loosely based on Mamá but drawing upon his own adolescent experiences at an all-boy’s boarding school and gender-swapping the characters.

Serrador has discussed several significant influences on his script including fellow Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel who had experimented with narrative structure in films like The Exterminating Angel (1962)—which also takes place in an enclosed, seemingly inescapable mansion. Specifically, Serrador cited Buñuel’s earlier Viridiana (1961) as a key influence for its exploration of gendered power dynamics, as well as its brave critique of religious, social, and political repression.

Previously, he’d adapted stories by Edgar Allan Poe in his anthologies for television and several of the author’s key themes that define the Gothic resurface in The House that Screamed. Rather than relying on the jump-scares or gore, suspense builds through the psychological dynamics of the characters and the monstrous is revealed in the form of perverse desires and dark secrets. Poe’s setting for The Fall of the House of Usher is a dark, decaying mansion that symbolises the psychological corruption of its occupants who turn out to be a typically dysfunctional and doomed ‘Gothic family’. Likewise, the labyrinthine boarding school with its many dusty, neglected areas and locked rooms becomes a Freudian metaphor of psychological malaise. The staff and students form an extended, equally dysfunctional family.

With the help of cinematographer Manuel Berenguer, Serrador manages to imbue the house itself with a presence, as if the very architecture is voyeuristically witnessing events. Many of the sequences are shot subjectively, turning the viewer into a ghost and drawing them into the action. Here, production designer Ramiro Gómez is also due some credit for some beautiful sets. Although location filming took place at the Neo-Gothic Sobrellano Palace, near Santander in Spain—doubling as rural Provence—many of the interiors, such as the shower room, the secret ‘inner sanctum’, and cobweb-shrouded attic spaces, were shot at the studios in Madrid where sets were constructed with removable sections to allow filming from ‘impossible’ angles and in claustrophobic spaces, such as ventilation shafts.

Although it performed well on initial theatrical release in Spain, it met with mixed reviews and some decidedly hostile ones. It seems many top Spanish critics weren’t ready for intelligent horror or found its content at odds with the ideology of their Catholic dictatorship. The punishment and murder scenes were trimmed to reduce the intensity of the violent imagery and a couple of others were slightly censored: one line that expressed lesbian affection and a kiss with incestuous implications. Ironically, the versions released in the US and UK, titled The House that Screamed, suffered far worse under the censor’s scissors, with durations varying between 88 and 94-minutes.

Narciso Ibáñez Serrador went on to become hugely successful in Spanish mainstream television, eventually promoted to controller of its public channel and creating popular entertainment shows including the popular format for the gameshow 3-2-1 which was exported around the globe. Sadly, though, this allowed him little time to pursue cinematic projects, which is a great loss to genre cinema.

It’s probably because he made only two feature films, his second being Who Can Kill a Child? (1976), and both in the horror genre, that the importance of The House that Screamed has been overlooked, with more prolific auteurs stealing the limelight (Argento springs to mind). For so long, it’s been a footnote in horror histories. There have been a couple of decent DVD releases in some territories and a US Blu-ray in 2016 spliced together unrestored clips to recreate the full print, but apart from dodgy VHS copies and poor prints disseminated online, it’s been a difficult film to source in the UK and one I’ve managed to avoid… until now.

So, this excellent 2K restoration from the original negative is a very welcome Blu-ray release indeed. The Eastmancolor palette is gorgeous and probably the best it’s ever looked. Censored scenes have been restored with the uncut version running at its full 105-minutes, as intended. In recent years, The House that Screamed has been re-evaluated and gained the recognition it richly deserves as a landmark in horror cinema and, although some of the tropes it establishes have since become familiar, it remains essential viewing.

SPAIN | 1969 | 105 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

director: Narciso Ibáñez Serrador.

writer: Narciso Ibáñez Serrador (story by Juan Tébar).

starring: Lilli Palmer, Cristina Galbó, John Moulder-Brown, Mary Maude, Maribel Martín, Pauline Challoner & Cándida Losada.