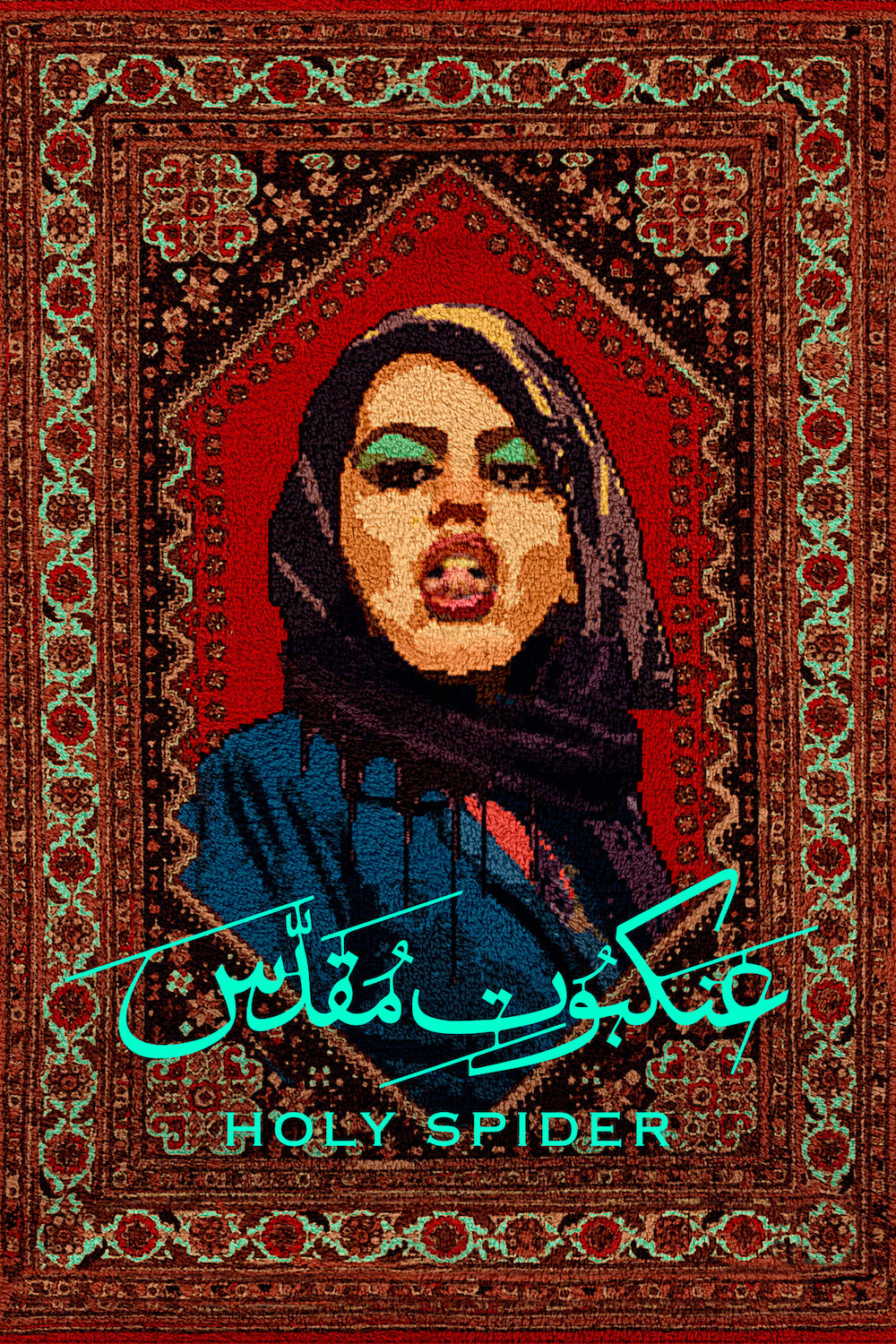

HOLY SPIDER (2022)

A journalist descends into the dark underbelly of the Iranian holy city of Mashhad as she investigates the serial killings of sex workers by the so-called 'Spider Killer'...

A journalist descends into the dark underbelly of the Iranian holy city of Mashhad as she investigates the serial killings of sex workers by the so-called 'Spider Killer'...

Lately, there’s been a kind of tragic relevance permeating the more internationally renowned corners of modern Iranian cinema. For one, the country’s infamous legal requirements and punishments imposed on its filmmakers have affected an untold number of its most recognized cinematic visionaries—most prominently Jafar Panahi’s recent arrest and six-year prison sentence, which has drawn a long shadow over his latest work, No Bears (2022), the culmination of a 20-year-long ban on filmmaking that still failed to stop him from making five features in secret within that time. His son, Panah Panahi, rocketed into the international film scene with his boldly naturalistic debut Hit the Road (2021), a subtly emotional indictment of the Iranian government’s repressive instincts, which was promptly banned in its home country from release. Meanwhile, the government’s arrests against other cinematic figures speaking out against its fundamentalism, censorship, and violent anti-protest crackdowns—among them being director Mohammad Rasoulof (There is No Evil) and actress Taranah Alidoosti (The Salesman)—has drawn significant outcry from cinematic industries worldwide, and served as a devastating display of the cultural dangers that corrupt governments can threaten on their most renowned artists.

Overlapped on top of this is a violent reckoning over Iran’s history of institutionalised misogyny. In the wake of Mahsa Amini’s recent death at the hands of the Iranian Guidance Patrol (widely dubbed the “morality police”) for a supposed violation of Iran’s mandatory hijab law, as well as the blazingly indignant protests that have erupted in response to it, the fight for women’s rights in Iran has reached a furious high, drawing the attention of the international community to how deeply Iran has entrenched the repression of said rights into both its laws and implicit moral codes. One of the more infamous historical examples of such repression is the ‘Spider Killer’ Saeed Hanaei, who deliberately targeted and murdered 16 sex workers in the Iranian holy city of Mashhad from August 2000 to July 2001. His ‘Spider Killer’ moniker was a result of his method, as nearly all of these women were lured to and killed in his own apartment.

Enter writer-director Ali Abbasi, whose latest work, Holy Spider / عنکبوت مقدس, serves as his first feature film set in his native land. That’s no accident; while he was born in Iran, Abbasi currently lives in Copenhagen, and his first two features, Shelley (2016) and Border (2018) were made in Denmark and Sweden, respectively. But Abbasi’s return to Iran marks the fulfilment of a source of intrigue that’s been plaguing him for years—that of the Spider Killer and how he was both created and endorsed by the fundamentalist society around him. As a result, it comes as no surprise Holy Spider is an indignantly angry film; at once a searing portrait of Hanaei’s twisted misogyny and the brutality of his crimes, as well as a semi-fictionalized portrayal of the corrupt patriarchal systems that implicitly uplifted his actions. And while the bifurcated approach it takes to the genre is what drastically muddies its potential impact throughout the story it tells, the lingering impact of its statement on what Hanaei’s actions implied about the bleak state of women’s rights in Iran before and after his killing spree will still likely stay with audiences long after its haunting final frame cuts to black.

Holy Spider alternates between two protagonists on complete opposite moral ends, following both Saeed’s (Mehdi Bajestani) viciously misogynistic crusade, and Arezoo Rahimi (Zar Amir Ebrahimi), a fictionalized journalist determined to uncover the truth behind the Spider Killer’s murders, in a zig-zag narrative structure that affords nearly equal amounts of runtime to both arcs. Saeed’s identity as the Spider Killer is unveiled almost immediately—in the film’s opening moments, we watch as a sex worker endures near-constant abuse from her clients before running into Saeed and later being brutally strangled to death with her own headscarf in the stairwell up to his apartment. He’s shown to be a man whose murderous rampage is the result of a life without purpose; having emerged from the brutality of the Iran-Iraq War without having attained any sort of religious martyrdom in death, Saeed has turned his zealous devotion to Islam and Imam Reza into a killing spree, all of which is done in the name of cleansing what he sees as “corruption” from the streets of Iran. Adding to the sheer whiplash of the Saeed’s internal contrast is the depiction of his family life—to all who know him, he appears to be no more than a devoted husband and a father of three.

Rahimi, on the other hand, carries first-hand experience with misogyny in her personal life as well as her career in journalism, and only comes to endure more of it as her investigation into Saeed’s murders deepens. Her first scene is that of her trying to check into a hotel, in which the concierge only lets her through once she proves she’s a journalist, despite her having a reservation for a room to begin with. Further encounters involve an unnervingly skeevy detective named Rostami (Sina Parvaneh), as well as several nods to a past involving an editor that fired her because of how she rejected his advances. But Rahimi’s steadfast determination—amplified partially by the anger she feels not just from her immediate circumstances but also the shadow of misogyny looming large with Saeed’s murders—-is what prevents her character from backsliding into platitudinous predictability, supported by Ebrahimi’s fiery performance, as well as the distressing degree of realism behind her every unsettling encounter.

Holy Spider is very much a balancing act between the exploitation-ish narrative path Saeed takes on—perhaps a more grounded and less blatant successor to films like Angst (1983) or Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986)—and the journalistic deep dive into corruption that Rahimi’s story amounts to. It’s difficult to deny both of these narrative threads are given their fair due; Rahimi’s downward spiral into the rabbit hole of Iran’s institutionalized misogyny is constructed with confrontations that evidently draw from a bitter social reality, while Saeed’s arc simultaneously emphasises his brutality as well as the convictions, beliefs, and attitudes he holds in his personal life. The film’s technical craft only further serves to explicate the story’s pervasive tension and refusal to hold back on the graphic details—-significant amounts of handheld camerawork merge with claustrophobic framings from cinematographer Nadim Carlsen and bluntly straightforward editing from Hayedeh Safiyari and Olivia Neergaard-Holm to the incredibly direct and oftentimes gritty visual effect. Individually and taken at face value, though, these two storylines don’t quite exceed the expectations their premises suggest, even if they certainly fulfil them with thorough enough explorations of these characters; this holds particularly true for Rahimi’s story, which can often feel like your everyday typical noirish procedural labyrinth through the darker corners of society with the exception of a few particularly disturbing scenes.

The film’s main structural issue is that it is a balancing act, to begin with; one that operates between two incongruent modes of crime-thriller storytelling that shrilly clash when placed directly next to each other. For Rahimi’s story and its social criticism to fully work, it requires a sensitivity that bluntly including graphic depictions of Saeed’s killing spree can’t necessarily fulfil. For Saeed’s killing spree to truly impress its misogynistic horror on its audience, its impact needs to extend beyond the brutality of his crimes into the implications of what they mean for the world around him, something that Rahimi’s story often takes great pains to spell out. But as these two paths inevitably end up crossing, the way they partially detract from each other gets somewhat evened out as Holy Spider completely indulges in a particular angle that suddenly provides a jarring perspective on the impact of Saeed’s murders, primarily told through his family’s perspective in a harrowing series of events that culminates in a deeply unsettling conclusion.

It’s also largely to Holy Spider‘s benefit that the talent standing both in front of and behind the camera helps to smooth out the incongruities between its parallel storylines, giving the overall film a sense of consistency that effectively masks the narrative turmoil lying beneath. Zar Amir Ebrahami, for one, is bringing real-life ire to Rahimi’s indignant determination: having emigrated to France after her career in Iran was decimated by leaks of a sex tape, Ebrahimi has had an up-close experience with the professional and personal risks that Iran’s institutionalized misogyny poses to the women living in it, and carries that awareness into Rahimi’s character, a turn so convincing and strikingly angry it makes her Best Actress win at last year’s Cannes Film Festival deeply impressive. Meanwhile, Mehdi Bajestani injects so much self-righteous vitriol into the role of Saeed that it helps to elevate such a murderous character beyond the contrivances found in typical fictionalized-true-crime fare and the killers they depict. Every action Saeed takes is, at the very least, given narrative sufficient context both in the character’s life and from the world around him, and Bajestani does what he can to bring the sheer degree of religious zealotry and patriarchal delusion necessary to depict Saeed as a demonic product of his time.

Holy Spider may not amount to much more than an unusual clash between completely average true-crime exploitation and journalistic procedural tossed into one movie, but the discomfiting relevance of its ideas and the clear anger through which it chooses to present them is what allows its final 30 minutes to flourish. One of the most terrifying things about Saeed Hanaei is that even upon his arrest, religious fundamentalists became aware of and publicly upheld his misogynistic cause to the bitter end, frequently citing him as an ideal moral example. And it wasn’t just extremists, the morality police, or Islamic militants who praised his murders—so did his family, his neighbours, and his closest friends. The verdict that was eventually reached is almost entirely irrelevant; it was what he did and the profoundly sexist impact he left behind that makes the case of the Spider Killer so particularly morbid.

Above all else, Abbasi knows this; it’s what he pivots the film’s narrative course to in its final stretch, leaving audiences with the horrific notion that even the newest, youngest generations of Iranian citizens would have succumbed to such bigoted instincts in the name of religious, familial, and governmental piety, regardless of the trial’s outcome. It’s an observation that only makes Iran’s current state in modern history that much more harrowing in its scale and how widespread the issue of misogyny in Iran has become… yet it could have left a genuine, lasting mark if the film had decided a single, more complete way of building up to it.

DENMARK • GERMANY • FRANCE • SWEDEN • JORDAN • ITALY | 2022 | 116 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | PERSIAN

director: Ali Abbasi.

writer: Ali Abbasi & Afshin Kamran Bahrami.

starring: Zar Amir Ebrahimi, Mehdi Bajestani, Arash Ashtiani, Forouzan Jamshidnejad, Sina Parvani & Mesbah Taleb.