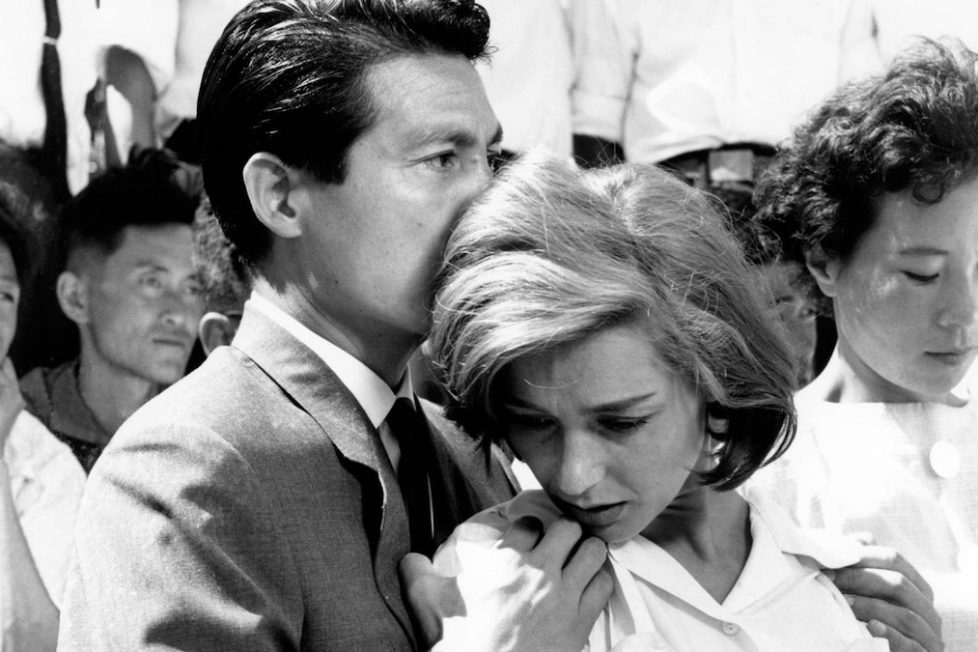

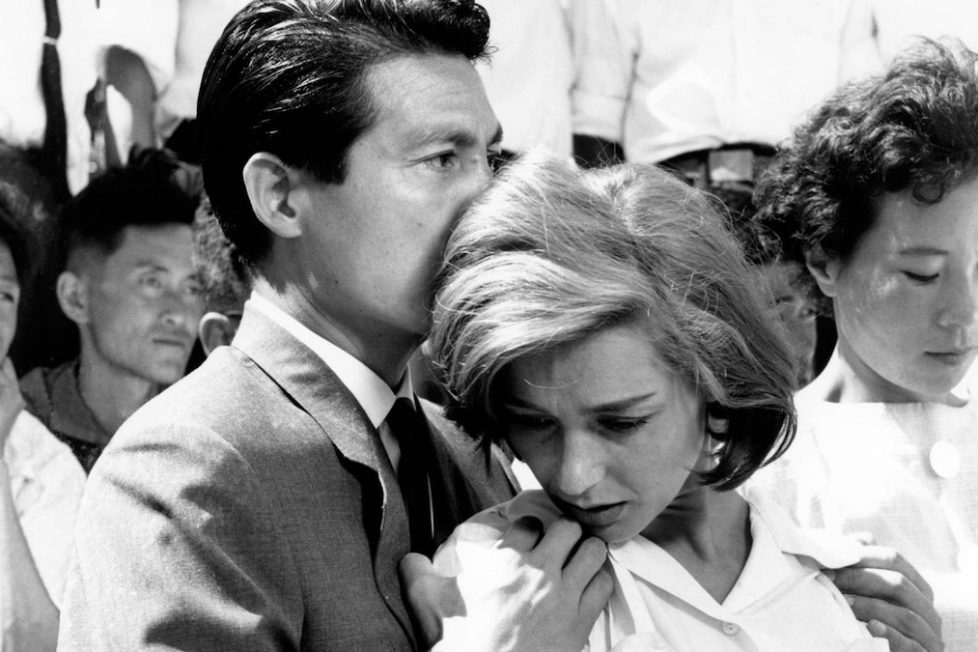

HIROSHIMA MON AMOUR (1959)

A French actress filming an anti-war film in Hiroshima has an affair with a married Japanese architect as they share their differing perspectives on war.

A French actress filming an anti-war film in Hiroshima has an affair with a married Japanese architect as they share their differing perspectives on war.

Alain Resnais had made documentaries before his first narrative feature, Hiroshima Mon Amour, and the coexistence here of superficially objective reportage with long and intimate, sometimes philosophical conversations between its two characters is just one of many ways in which it challenged audiences’ expectations of film.

It continues to do so even today, more than 60 years after its release; years in which Resnais’ blending of fact and fiction and his non-linear treatment of timelines have become more common (though still not mainstream). Hiroshima Mon Amour thus remains startlingly fresh and original.

Nothing in the movie is to be entirely trusted. “You think you know but you don’t, never”, says Elle (Emmanuelle Riva), and indeed it’s noted that the entire tragic tale she recounts of romance with a German soldier in occupied France might simply be made up.

The awful visitation of August 1945 on the city of Hiroshima, where Elle some years later finds herself in another, briefer affair with a Japanese man (Eiji Okada) is obviously not made up; but even so, is it possible for Elle to understand what happened here?

In a famously repeated line, the man tells her “you saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing.” She might have seen reconstructions or photos, or visited museums, but she didn’t experience the thing itself.

Hiroshima Mon Amour is a film about not knowing, about losing knowledge as the past slips away, or never even being able to attain it in the first place; a film where the emotional truths are powerful but the literal ones are defined more by their absence. “The entire film was to be built on contradiction,” said Resnais, “that of forgetfulness, at once essential and terrifying.”

This disorienting principle also extends to its style: time is disjointed, some flashbacks are only glimpsed (though others are longer), and the sequence of events isn’t always clear. In one of the movie’s most memorable passages, Elle seems to wander through nighttime Hiroshima and her French home town, Nevers, simultaneously.

Éric Rohmer, a later-arriving director of the French New Wave, compared Resnais to a Cubist, first shattering reality and then reconstructing it. This ambiguity is evident from the first shot, appearing to show limbs covered in what might be ash: one of the dead of 1945, perhaps? But slowly we realise we’re seeing a couple, a living couple, and the effect is as strangely discomfiting as the title (imagine putting “Hiroshima” and “love” together not 15 years after the event).

It’s a long time until we see their faces, but eventually we get to know a little about them. Elle is a French actress, in Hiroshima to make an anti-war film. (Though Hiroshima Mon Amour itself is clearly anti-war too, Resnais seems to gently lampoon the movement in the excessively wordy, didactic banners carried at a protest march staged for Elle’s movie.) Her Japanese lover, Lui, is an architect; his family were at Hiroshima when the Bomb fell, though he was away on military service.

Their relationship sometimes seems more combative than affectionate, but not because they were nominally on opposing sides during World War II. Neither guilt nor accusation is overtly on display. Instead, as they discuss their current situation and their respective pasts (especially hers; Lui is often little more than a sounding-board for Elle), what comes through most strongly is a struggle for comprehension of the other’s experiences.

The absence of shared memories, just like the impossibility of her really understanding what Hiroshima was like in 1945, seems to put a distance between them. And given that the two characters’ names mean simply “her” and “him” in French, it’s clear that they stand for a more general human problem.

In a famous final moment, they decide to call each other by the names of their cities–he Hiroshima, she Nevers—and indeed the repetition throughout of the word “Hiroshima”, and of place names in general, suggests a desperate attempt by people adrift to somehow ground themselves in a solid reality.

The film is full of contradictions—“you’re destroying me, you’re good for me”, she says to him—but also full of tantalising parallels. Cats, for example, figure in different times and locations. Elle, as a collaborator in Nazi-occupied France, has her hair cut off just as we have seen survivors of Hiroshima lose theirs to radiation. Resnais is not saying here, of course, that the experiences were equivalent in an objective way: just that there can be commonality to experience, however difficult it is to pin down.

That elusivity is a central concern of Hiroshima Mon Amour, and if it is a slippery film to grasp that’s completely intentional. Still, Resnais— and the novelist Marguerite Duras, who received an Academy Award nomination for this, her first screenplay—also suggest that the cinema can help us to understand. “Looking carefully at things can be learned,” Elle suggests. “Have you ever noticed that we always notice what we want?” Lui asks.

Philosophical points aside, there is much to notice on a purely cinematic level in Hiroshima Mon Amour too.

The footage of the city, both immediately after the Bomb and in the 1950s, is historically fascinating in itself. The anti-nuclear protest is beautifully shot in the way it builds from calm to great energy (and for a movie that is mostly static in the sense that the characters don’t do much except talk or contemplate, Resnais maintains a remarkably mobile camera throughout). A scene at the Casablanca bar toward the end—spot the Hollywood reference to lovers torn apart by war—is brilliantly unexpected, and devastating.

The superb score by Giovanni Fusco (a frequent collaborator with Michelangelo Antonioni long before Hiroshima Mon Amour) and Georges Delerue does much to heighten the intensity of Resnais’ film, too, often through stark contrasts between grim subject matter and apparently lighter music.

Fusco’s contribution is generally Stravinskian in mood, and could easily stand as a composition in its own right (indeed, it was made into a concert suite); Delerue wrote a waltz. Resnais had originally wanted the Italian serialist composer Luigi Dallapiccola, who turned him down, but it’s difficult to imagine how the existing score could be improved on. Its rhythmic character is important, too, in reflecting both the patterns of Duras’s dialogue and the larger structure of the film, which Resnais compared to a theme and variations.

Resnais had already made his name as a documentarian, most notably with Night and Fog (1956), and indeed Hiroshima Mon Amour was first conceived as a documentary. But he decided to approach the subject through fiction instead, with the Bomb “in the distance, a kind of landscape” (as he says in one of the supplements here).

The result is “a film about love set in Hiroshima, the cradle of anxiety” (as Riva says in another), also a film about remembering and not remembering, about connecting and the inability to connect, about the difficulty of truly knowing another person.

He continued to make films for the rest of his life—his last was premiered weeks before he died in 2014—but it is surely for Hiroshima Mon Amour as well as Last Year at Marienbad (1961) that he will be best remembered, and rightly so.

In formal terms, it was radical. The idea of multiple timelines was nothing new, of course, and indeed Resnais himself acknowledged the influence of D.W Griffith’s Intolerance (1916). But his film went much further in breaking down the barriers between times, and in doing so it set a precedent taken up by many later movies from Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964) to Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000).

In Hiroshima Mon Amour the integrity of time itself, and indeed space, seems questioned. Sometimes there is little sense that the Nevers of the 1940s is distant from the Hiroshima of the 1950s, yet it is also unattainably distant. The Hiroshima of 1945 is both ever-present in the city of a decade later, and all but vanished. Elle and Lui are unbridgeably separated from one another despite existing in the same time and place, in an apparently close relationship.

Hiroshima Mon Amour does not resolve these contradictions, and that’s where its fascination lies. It still has the capacity to surprise and intrigue precisely because there are no answers. Criterion’s reissue won’t provide answers either, but it does provide a beautiful restoration of one of the most important films of its period, and a well-chosen set of supplements which at least help to clarify the questions.

FRANCE • JAPAN | 1959 | 90 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | FRENCH

director: Alain Resnais.

writer: Marguerite Duras.

starring: Emmanuelle Riva & Eiji Okada.