DEAD MAN (1995)

On the 19th-century American frontier, an accountant becomes an unlikely gunslinger...

On the 19th-century American frontier, an accountant becomes an unlikely gunslinger...

Virtually every western has been “revisionist” in rejecting the certainties of the mid-20th-century, but Jim Jarmusch’s only foray into the genre, Dead Man, is more revisionist than most. Not only does it portray the wild west as characterised more by ruthless, violent greed than by a high-minded mission to spread civilisation (as has been standard since the 1960s and 1970s), but it also has fun with the way revisionist ideas had, by the 1990s, become clichés in themselves, in one of its best lines satirising the trope of the wise Native American speaking philosophical truths in cryptic metaphor: “I’ve had it up to here with this Indian malarkey,” William Blake (Johnny Depp) tells Nobody (Gary Farmer). “I haven’t understood a single word you’ve said since I met you.”

The irony goes deeper still. One of the reasons Blake can’t understand Nobody is that the latter is labouring under the illusion that Blake-from-Ohio is the English poet William Blake (of whom Blake-from-Ohio has never heard), and Nobody is in fact often quoting lines from Blake’s namesake rather than handing down ancient wisdom.

When Blake-from-Ohio eventually asks someone “do you know my poetry?”, it’s the poetry that comes from the end of a gun he’s talking about, and by this point he’s starting to superficially resemble a Native American too. The white easterner seems to have become thoroughly part of the west, while Nobody is still revering at least one part of the colonists’ culture. Again, this wryly inverts the common narrative of newcomers imposing their values on a native community with far deeper roots—which isn’t to say Dead Man is terribly positive about the white men as a whole, either.

The misunderstandings between the pair begin with their first encounter—an injured Blake awakens to find Nobody straddling him with a knife and presumably imagines Nobody is about to kill him, rather than trying to remove a bullet from his chest—and persist to the last lines of the movie. But Dead Man isn’t just the knowing, postmodern riff all this might suggest. It’s a multilayered film which, in its slightly crazy assemblage of elements, manages to create depth of feeling as well as delivering plenty of superficial smarts; as critic Amy Taubin has suggested, Jarmusch’s work is more visionary than (just) revisionist.

It all starts on a train. It’s the 1870s and Blake is an accountant from Cleveland, Ohio, whose parents recently passed away and his engagement broke off. He’s travelling out west—to the end of the line—“all the way out here to Hell”, as the train’s fireman (Crispin Glover) says—where he’s going to take up a job promised by letter. “I wouldn’t trust no words writ down… you’re just as likely to find your own grave,” warns the fireman.

Blake arrives at the town of Machine, expecting to become an accountant at the metalworks owned by John Dickinson (Robert Mitchum). This settlement is an infernal place; filthy, devoid of romance and alarmingly full of reminders of mortality, skulls litter the street, a coffin-maker works away in the background, and prostitutes service their clients in alleys. The clerks at Dickinson’s factory (led by John Hurt) are hostile, smirking Dickensian figures, and their employer is a tyrannical monster.

Despite his protests, Blake’s denied the job he’d come for, but he briefly takes up with Thel (Mili Avital), a seller of paper flowers (in that respect a precursor, maybe, of Kodi Smit-McPhee’s character in 2021’s The Power of the Dog?), and more importantly the ex-girlfriend of Dickinson’s son Charlie (Gabriel Byrne). Inevitably, the jealous Charlie surprises Thel and Blake together, and in the ensuing confrontation, Charlie is killed while Blake is wounded but manages to escape. He passes out and, on waking, finds himself being tended by Nobody.“Did you kill the white man who killed you?”, asks Nobody, to which Blake replies “I’m not dead”, although there remains a persistent question mark over that.

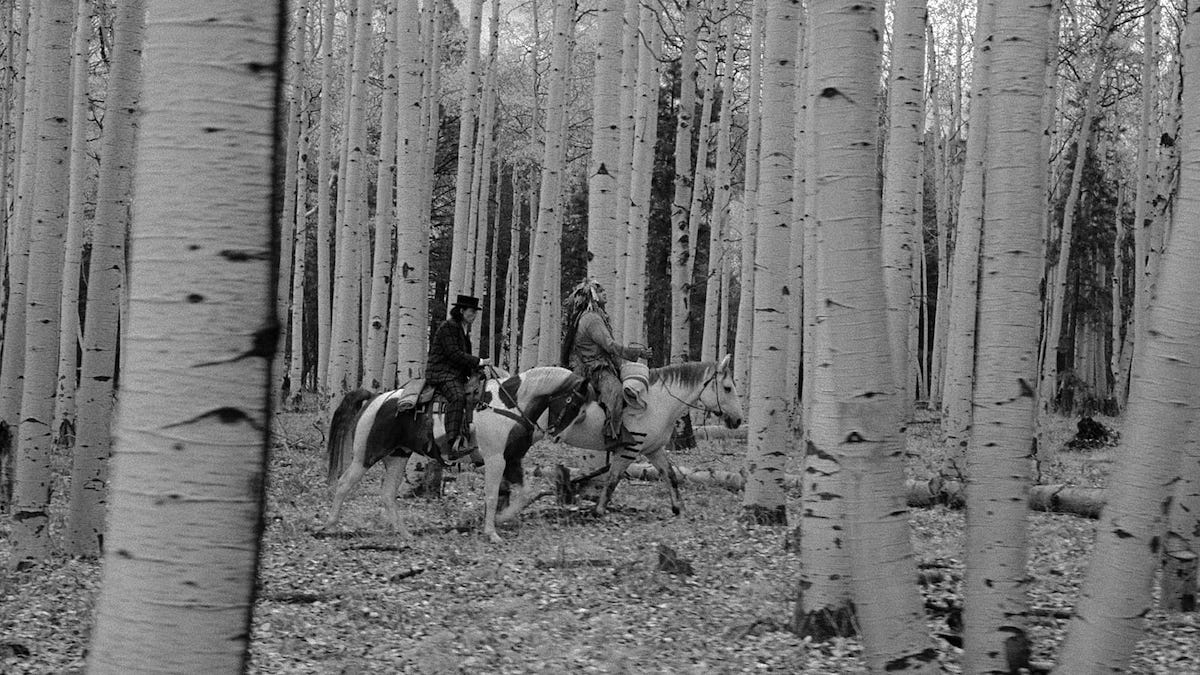

The remainder of the film follows Nobody and Blake as they travel further west, pursued by a series of killers dispatched by Dickinson to avenge the death of his son, or simply seeking the ever-increasing bounty on Blake’s head. The moment where Blake first comes upon a poster advertising the $500 reward (rather absurdly stuck on a tree in the middle of a forest) is a pivotal one in his transition from proper eastern accountant to the wild western gunslinger, as will be the loss of his glasses.

Dead Man is an episodic film, characteristically of Jarmusch, which for much of its two hours moves back and forth between Blake/Nobody and three bounty hunters (Eugene Byrd, Lance Henriksen and Michael Wincott), fading to black each time. Jarmusch said he hoped “scenes would resolve in and of themselves without being determined by the next incoming image.” This, it has been suggested, gives it an almost poetic structure—quite separate from its often poetic language and mood—in which the parallels between the two threads constitute “rhymes”. For example, Nobody asks Blake for tobacco, and then in the next scene, one of the three killers asks his two companions exactly the same question.

But though poetry and the idea of Blake-the-poet are ever-present in Dead Man, it’s firmly about Blake-from-Ohio, and the genuine Blakean references (Thel’s name, for instance, clearly comes from Blake’s Book of Thel) are mixed in with misleading ones. Some of Nobody’s lines which sound like they ought to come from literature, such as “things which are alike in nature grow to look alike”, don’t in fact. Blake misunderstands Nobody, Nobody misidentifies Blake, and the audience could easily be misled too.

This could all make for a rather contrived, over-engineered film were it not for how individual moments are often so humanly believable, and the two central characters so engaging even if we never fully understand what’s driving them.

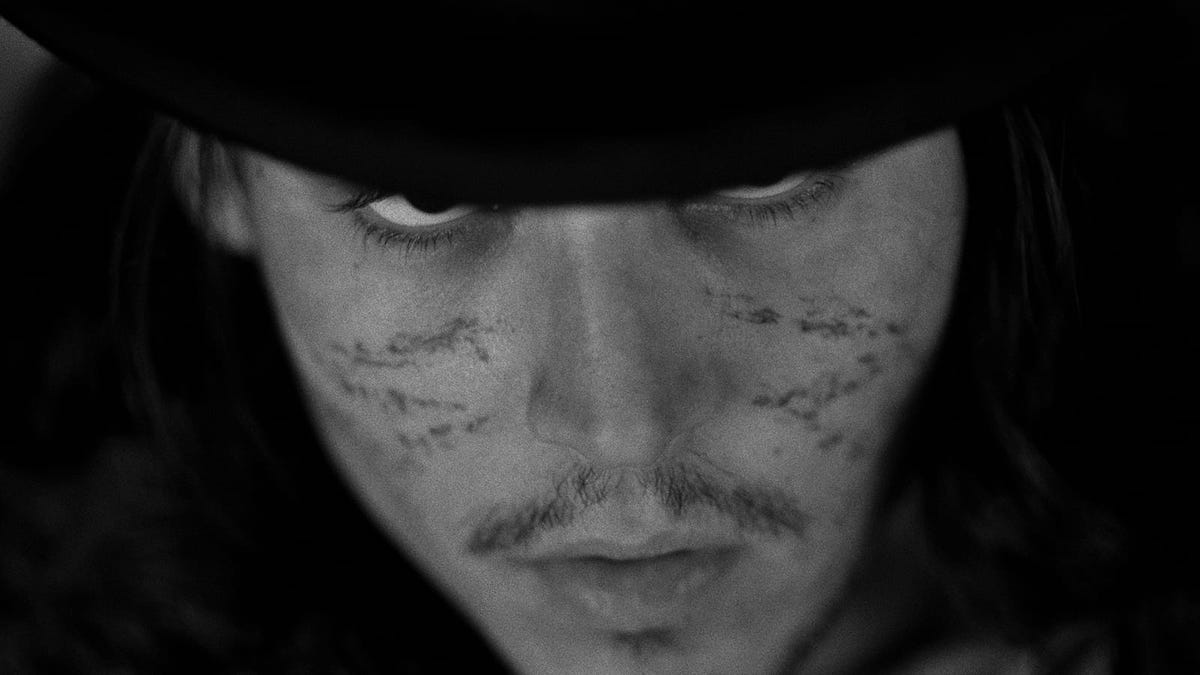

The young Johnny Depp is so well-suited to the role of Blake that it’s a pity he didn’t do more westerns; the character is fragile and strong at the same time, perhaps surprising himself with his own strength (or deluding himself about his own fragility). He can seem uncomfortable physically, sometimes oblivious to what’s going on and at other times over-wary—when he sees Native American tipis out of the train window he draws his bag closer to his chest. Yet he can also wade assuredly into situations (perhaps because he’s oblivious?) and he becomes an efficient and unconcerned killer. He can seem prissy (“I have a sneaking suspicion that that large man was inebriated”), he can seem comically bland and nerdish (reading Bee Journal on the train), but Depp never caricatures this side of him, presenting it only as a baseline from which Blake can grow. The character may not always learn (he can still be naive right to the end) but he certainly changes or discovers something unknown in himself.

Farmer’s Nobody is equally complex, unlike most Native American characters, with Jarmusch saying “I wanted him to be a complicated human being.” (He also appears in 1999’s Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai, another genre exercise, which was the director’s only other fiction film in the 1990s.) While he’s as far removed from the noble savage of historical Hollywood as one can imagine, being a rotund and self-satisfied Native American version of Jack Black, he’s also (despite his other moniker of ‘He Who Talks Loud Saying Nothing’) more perceptive than Blake, recognising early on (as Blake doesn’t) that what this particular white man really needs is to find the proper route toward death and the spirit world.

Nobody is something of an outcast, too, partly thanks to his half-Blood, half-Blackfoot heritage but also because his forced sojourn in Britain (whence comes his knowledge of Blake-the-poet) sets him apart from most of his people. Just as Blake will come to, he occupies a hazily-defined borderland between societies. Though Jarmusch’s treatment of both characters is often gently humorous, Farmer (like Depp) doesn’t play to this excessively. Native American critics were actually impressed by the film, including its awareness of the differences between tribes.

Also standing out in the large and name-studded cast is Mitchum, in his last screen role, and Hurt as his amusingly unpleasant office manager. But the real third star of Dead Man is Neil Young’s score, improvised and mostly performed on a single electric guitar, which punctuates the film with variations on a few ideas. Jarmusch’s next movie would be the documentaryYear of the Horse (1997), for which Young invited him to follow the musician and the band Crazy Horse on tour.

Dead Man is a thoughtful film, on many levels, and at times a contemplatively gorgeous one in much of Robby Müller’s cinematography with the stillness and beauty of the peyote scene, for instance. But Jarmusch also has much fun with the details, some of them outright comic, others more understated. There are marshals called Lee and Marvin; the hired killer who sleeps with a teddy bear; the way that Blake, buying whiskey in a Machine saloon, finds his bottle swiftly snatched away and replaced with a smaller one when his coins are insufficient; the way that at the metalworks he asks for directions to the office while standing beneath a sign with a big arrow and the word ‘OFFICE’.

There’s also the killer who, surveying another’s body, comments how he “looks like a goddamn religious icon”—Jarmusch there lampooning the self-consciously grandiose tragedy of many movies’ death scenes. There’s the running gag about tobacco, extended to the final seconds of the movie (Blake, asked for it, repeatedly tells Nobody that “I don’t smoke”, failing to grasp that to Nobody’s people it’s a ritual item). There’s the dig at blackface when Crispin Glover’s fireman, his face dark with soot, sits down to talk to Blake on the train. And there’s the bizarre trio of trappers (Jared Harris, Billy Bob Thornton, Iggy Pop) who are more interested in Blake’s shoes and the softness of his hair than with manly trapper pursuits, whose beans may well be a reference to Blazing Saddles (1974), and who resembles nothing more than ‘The Knights Who Say Ni’ from Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975) brought forward a few centuries. They resemble, too, the three bounty hunters: another example of Dead Man’s “rhymes”.

Touches like these add piquancy to what otherwise might be a solemn movie, but never detract from Dead Man’s thematic richness. One of its biggest concerns is, as the title suggests, mortality. Juan A. Suárez, in his book on Jarmusch, called the movie “essentially a protracted dying scene”, and it’s arguable (though certainly not provable) that the bulk of it is a hallucination in the last moments of Blake, mortally wounded by the bullet in Machine. In the peyote scene, for example, Nobody sees Blake’s face as a skull; later, when a pious but insincere missionary at a trading post (Alfred Molina) says to Blake “God damn your soul to the fires of hell”, the response is (of course) “he already has.”

There are a few existential ideas running through the movie too, especially the pernicious role of the white man’s capitalism. The frontier here is far from an idealised place where settlers are free to make a happier life than the one they left behind. Machine is an extreme, raw version of the east with its pretensions to civilised values stripped away. On the train, heading from east to west, Glover’s fireman even alludes to a feeling of being immobile while actually moving; this machine is a constant, unaffected by the changing landscapes it passes through.

And perhaps, though Nobody repeatedly calls Blake “stupid white man”, it’s just not white men specifically (or what Blake-the-poet described as their “dark satanic mills”) but people in general who despoil the world. Though the gargantuan trees and dense undergrowth of the final scenes in the Pacific Northwest suggest a return to an Edenic state of nature, when Blake and Nobody finally reach the Makah settlement it oddly—and depressingly—resembles the town of Machine, right down to the bones on display along its street. As Jonathan Rosenbaum has said, it’s “as if Jarmusch wanted to give us a version of the classic western reconfigured as some sort of nightmare.”

Dead Man marked a change in direction for Jarmusch, whose previous films had been smaller-scale, smaller-budget, and more dominated by ensembles than specific protagonists. But it also displayed many of the traits with which the director was already associated, like its humour, its recurrent failures of people to properly understand each other, and in what Suárez described as the director’s tendency to be both realistic and stylised. This duality runs through the film, from the production design for the town of Machine (Deadwood authenticity fused with morbid grotesquerie), to the character of Nobody, to the way that the screenplay mixes literal misunderstandings with metaphorical ones (Blake missing out on the job offer, Blake not grasping why Nobody asks for tobacco).

Jarmusch refused to make further cuts when asked to (much to Harvey Weinstein’s displeasure), and though the deleted scenes on this Criterion Blu-ray suggest those the director did approve weren’t significant losses, any more would surely have weakened it—for this is a movie whose effect comes from progressive change both in the nature of Blake and in the places he moves through. The receding opening titles already suggest a journey, and for Blake it’s not just a physical one—his final destination with the Makah is important, but the act of getting there is essential too.

For audiences, as well, much of the reward in Dead Man comes not from the film as a whole but from the moments along the way.

USA | 1995 | 121 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH • NATIVE AMERICAN LANGUAGES (INCLUDING BLACKFOOT, CREE & MAKAH).

writer & director: Jim Jarmusch.

starring: Johnny Depp, Gary Farmer, Billy Bob Thornton, Iggy Pop, Crispin Glover & John Hurt.