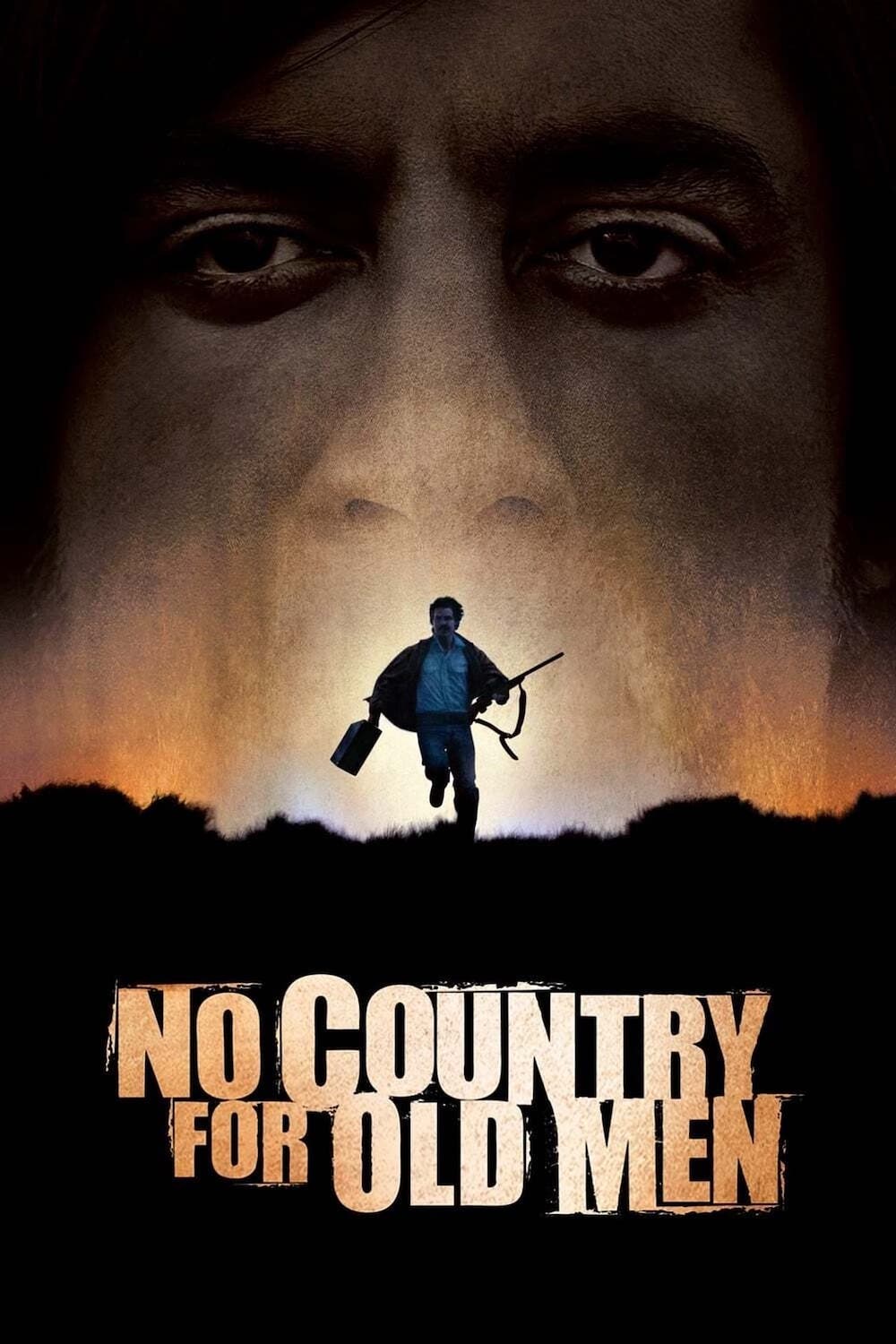

NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN (2007)

After a Texan man finds millions of dollars in the desert, he is pursued by both the local sheriff and a ruthless assassin.

After a Texan man finds millions of dollars in the desert, he is pursued by both the local sheriff and a ruthless assassin.

Ranked as the Coen Brothers’ finest film by many critics—and it would probably get to the top of more lists if Fargo (1996) weren’t more lovable—No Country for Old Men was also one of the most commercially successful movies of the mid-2000s indie boom. With a glossier feel than many indies, despite its grungy locations, it tells a lean and gripping tale of avarice and murder. No Country is less self-consciously eccentric than much of the brothers’ work (at least with the exception of Javier Bardem’s character), and it successfully exploits genre appeal without being confined by it.

Although it does have film noir elements, the feel is very much of an updated and slightly crazed western in which everyone is pursuing or being pursued, out for revenge or money, or (less commonly) justice. “You can’t help but compare yourself against the oldtimers”, says Tommy Lee Jones’s lawman in voiceover at the beginning of the movie. Indeed, the key characters are all updates of familiar western archetypes (the sheriff, the black-clad outlaw, the settler, the anxious wife, the bounty hunter, etc). The landscape is important too (“this country’s hard on people”) and though the film’s set in 1980, that hardly matters… it could easily be transplanted to 1940 or 2020 with little alteration. Only a few references to characters being Vietnam veterans would have to go.

Despite some small elisions, it follows Cormac McCarthy’s 2005 novel so exceptionally closely that many critics commented on its fidelity. (Perhaps it helped that McCarthy’s work began life as a screenplay). Set mostly in west Texas, with a detour south of the border, No Country for Old Men begins with its most memorable—if most opaque—character, hitman Anton Chigurh (Bardem), being arrested and then escaping custody. It soon switches, though, to the more laid-back Moss (Josh Brolin), a blue-collar guy whose appearance is as ordinary as Chigurh’s is bizarre, out hunting in the desert.

Wounding an animal, he tracks the trail of its blood (foreshadowing the metaphoric and literal trails of blood Chigurh will later leave) until he stumbles across a group of abandoned pickup trucks, corpses scattered around them. At the scene of this apparent drug deal gone wrong, Moss also finds $2.4M in a bag, and in taking it sets in motion the rest of the narrative. The money itself becomes something of a MacGuffin, but it’s the incident that gives each of the main characters a goal.

Moss’s aim throughout the film is simply to stay alive, keep the fortune, and protect his wife Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald) from increasingly dangerous circumstances. Chigurh is hired to recover the cash, although killing anyone who stands in his way (or anyone he feels deserves it) seems to be higher on his personal agenda. Local Sheriff Bell (Jones) is initially dealing with the bodies in the desert as just another crime, but soon realises what’s happened to the cash and turns his attention to reaching Moss before Chigurh can get to him. And the film briefly becomes a four-way cat-and-mouse once Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson), retained as a backup by Chigurh’s employers but working separately, also starts pursuing Moss.

“It’s a mess,” says Wendell (Garret Dillahunt), Bell’s deputy. “If it ain’t, it’ll do till the mess gets here,” Bell replies.

No more than two of the main four male characters are ever seen together, and indeed there’s little meaningful interaction between them. The marriage of Moss and Carla Jean is the only real relationship shown persistently throughout the movie, though Bell’s wife (Tess Harper) and his uncle (Barry Corbin) do appear in small but significant scenes. No Country for Old Men is more about how people relate to fate and death, and to odds that are sometimes overwhelmingly adverse, than about how they relate to each other, and its fascination comes both from the intricate mechanics of the multiple simultaneous manhunts and from the way the characters respond to them.

Settings (especially third-rate motel rooms) and physical objects can often seem as important as people, too. For example, a hidden transponder giving away a character’s location, or the bolt gun Chigurh uses for silent killing (a device later dropped into an innocent conversation between Bell and Carla Jean, for the benefit of audience members who can’t figure out what it is). Although the characters remain interesting throughout (thanks as much to superlative performances as to the screenplay), No Country for Old Men isn’t deeply concerned with them as individuals. They’re examples of kinds of people, and the things that happen to people.

As in Fargo–surely the Coen movie No Country for Old Men most resembles, despite other similarities to Blood Simple (1984)—there are moral contrasts. Stupidity, low cunning, and wanton violence do coexist here with decency. It’s clear that Bell’s a good man, Moss no worse than a forgivably flawed one, and Chigurh possibly a truly evil one. But for all that Jones’s Bell is an older, craggier version of Frances McDormand’s Marge in Fargo, he’s not as likeable or relatable in the same way; nor does Brolin’s character have the human depth of William H. Macy’s inept fraudster.

Still, it’s not that the people in No Country for Old Men are badly depicted. In fact, most of them are perfectly credible within the movie’s rather abstract context. It’s that exactly who they are is less important here than what they do and what becomes of them.

Early on it seems like Brolin’s Moss might be the most significant, and Jones’s Sheriff Bell doesn’t appear (though he does speak in voiceover) until about a half-hour into the movie, but very gradually the focus swings away from Moss toward him. The events of the movie may be primarily about or caused by Moss, but the meaning—and the relevance of the title—lie with Bell. Where Fargo’s Marge remained a cheery optimist at heart despite all the cruelty and corruption around her, Bell is in the process of throwing up his hands and giving in to disillusion. Indeed, perhaps the single most important scene for his character, though not one of the movie’s most famed, is his late conversation with his uncle Ellis (Corbin).

Here, Bell confesses he’s spent much of his life expecting to find some spiritual peace, but it hasn’t happened. Instead, he feels overwhelmed by the violence around him. Ellis replies that this part of Texas has been violent for generations–implying, as Chigurh does several times earlier, that it’s inevitable, inescapable—but he also observes: “All the time you spend tryin’ to get back what’s been took from you, there’s more goin’ out the door.” Regret is futile, he seems to be saying, and the difference between Bell and Moss is that Moss might agree, but Bell cannot avoid regret becoming despair.

Yet both of them, despite their dissimilarities, operate on recognisably the same moral scale. Way, way off it is Bardem’s Chigurh; a baroque creation, as implacably psychopathic a character as you will come across in any film, but one whose wild-eyed appearance when we first see his face is also misleading. He is out of control but also completely controlled, and what seems like senseless destructiveness to Bell makes complete sense to Chigurh; he not only relishes killing, he is even devoted to it in something approaching a religious way. Indeed, Wells points out that Chigurh, unlike the ordinarily harmless (if not scrupulously law-abiding) Moss, has principles—though he will also, once he finally confronts the killer, ask “do you have any idea how crazy you are?”.

The critic David Thomson suggested the character of Chigurh is “too lurid and wacky”, which is true to an extent in a film which is more naturalistic than much of the Coen Brothers’ oeuvre. But he’s supposed to stand out, to be exceptional, to be very unlike the others. Bell, in the film, compares him to a ghost. The Coens said they wanted to cast an actor who “could have come from Mars”. The cinematographer Roger Deakins has suggested he might even be the devil, though he seems to take a god-like attitude too; his changes of mood, from calmly homicidal to politely pedantic, are among his most disconcerting aspects (along with his famously awful haircut).

Perhaps Chigurh’s most famous scene is the one where he forces a gas station owner (Gene Jones) to bet his life on a coin flip. The stakes are never mentioned, but they’re obvious. Here we see the matter-of-factness with which the hitman regards murder, but what’s more chilling than the possibility he’ll kill an innocent man is the way the coin toss (repeated with another, more important character later in the film) seems to imply that for Chigurh, death and life (at least for others) are equal, and equally within his gift. It’s he who decides to confer either; it’s only to amuse himself that now and again he allows a randomly-determined outcome instead.

Brolin’s Moss, meanwhile, is at the other end of the lurid-and-wacky spectrum: an uncomplicated man who acknowledges his own limitations (he’s “fixin’ to do somethin’ dumber ‘n’ hell”, he admits to Carla Jean after deciding to keep the money he’s found), whose desires are simple, yet who’s stubborn enough to keep pursuing them even when things go wrong. There are occasional hints that the main characters are not as different as they might seem on the surface. For example, at one point Moss mentions that he only ever wears white socks, and the Coens later make a point of showing us Chigurh’s own.

But the most striking division in the movie is between the terrifying, incomprehensible Chigurh and everyone else. Even Harrelson’s Wells, although nominally a kind of colleague of Chigurh, has much more in common with Moss and Bell.

In a mostly male film, these outstanding four leads get fine support from Macdonald as Carla Jean (though her appearance as a working-class Texas gal seems slightly surreal nowadays given her close association with the BBC’s Line of Duty), while Dillahunt, Corbin, and Gene Jones also add much in minor roles. Even so, the fourth star of the movie after Tommy Lee Jones, Brolin, and Bardem is really the cinematography by Roger Deakins, a regular Coen collaborator and one of the best-known DoPs then and now.

The sparse dialogue, the empty desert, and the simple construction of many scenes are paralleled by an unassertive visual style. Sometimes Deakins and the Coens do point the viewer’s eye toward specifics when it’s needed, and occasionally the photography clearly refers to the events unfolding: when Chigurh is hunting down Moss in the town of Del Rio, for example, the hitman in his car is filmed in deathly grey-blue while Moss’s motel room is bathed in golden warmth. But for much of the film, the camera is little more than a passive recorder, and early on especially, many shots are almost still photographs. Whether the scene is in the Texas desert (itself an important although not dominant presence in the movie) or a town (most of them actually shot in New Mexico), this underlines the permanence of death and the limited capacity of individual humans to make a difference.

Yet there’s immense attention to detail, especially to lighting, important in a film where so much takes place at night. Particularly notable is one night-time sequence, where Moss is being chased across the desert. Without ever drawing too much attention to itself or detracting from the action, No Country for Old Men here provides so much atmosphere through its essentially naturalistic but slightly hyper-real shades and textures: yellow headlights in the darkness, metallic reflections off the surface of vehicles, refulgent shattered glass, the cold grey of dust like mist, then dust and headlights combined in a brilliant swirl, then a blue-black sky that gradually lightens without the rising sun itself becoming visible.

If Deakins’s cinematography is unshowy, Carter Burwell’s score is restrained to the point that you might be forgiven for imagining there was no music at all. But it is there, adding to the mood rather than dictating it. Given this, the scene where a filthy, bloodied Moss awakens on a Mexican street to be serenaded by a mariachi band must be the Coens’ joke about their own movie’s musical reticence.

No Country for Old Men was hailed from its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival and went on to win four Academy Awards—for ‘Best Picture’, ‘Best Adapted Screenplay’, ‘Best Director’, and ‘Best Supporting Actor’ for Bardem—as well as being nominated for film editing (by the Coens themselves), Deakins’s cinematography, and sound editing and mixing. Commercially it was a major profit-maker by indie standards, although of course still falling far short of the year’s more mainstream hits (which included entries in the Spider-Man, Shrek and Pirates of the Caribbean franchises).

Critics were almost unanimously enthusiastic and have remained so since. “Brilliant ingredients do not necessarily lead to a perfect meal, but in this case, it seems everything fell into its intended place,” wrote Sven Mikulec in Cinephilia & Beyond; the film was “the happiest marriage of novel to filmmakers for years”, suggested Nick James in Sight & Sound.

And as they imply, its appeal lies in its near-perfection. It is a film that says profound things, but they are not particularly original profundities; what makes No Country for Old Men so deeply satisfying is that the story is told and the profundities are expressed so, so well in every way, from script to photography to performances. The indisputable filmmaking brilliance of the Coen Brothers may sometimes be put to work in service of the silly or the self-indulgent, but never here.

USA | 2007 | 122 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

directors: Ethan Coen & Joel Coen.

writers: Joel Coen & Ethan Coen (based on the novel by Cormac McCarthy).

starring: Tommy Lee Jones, Javier Bardem, Josh Brolin, Woody Harrelson, Kelly Macdonald & Garret Dillahunt.