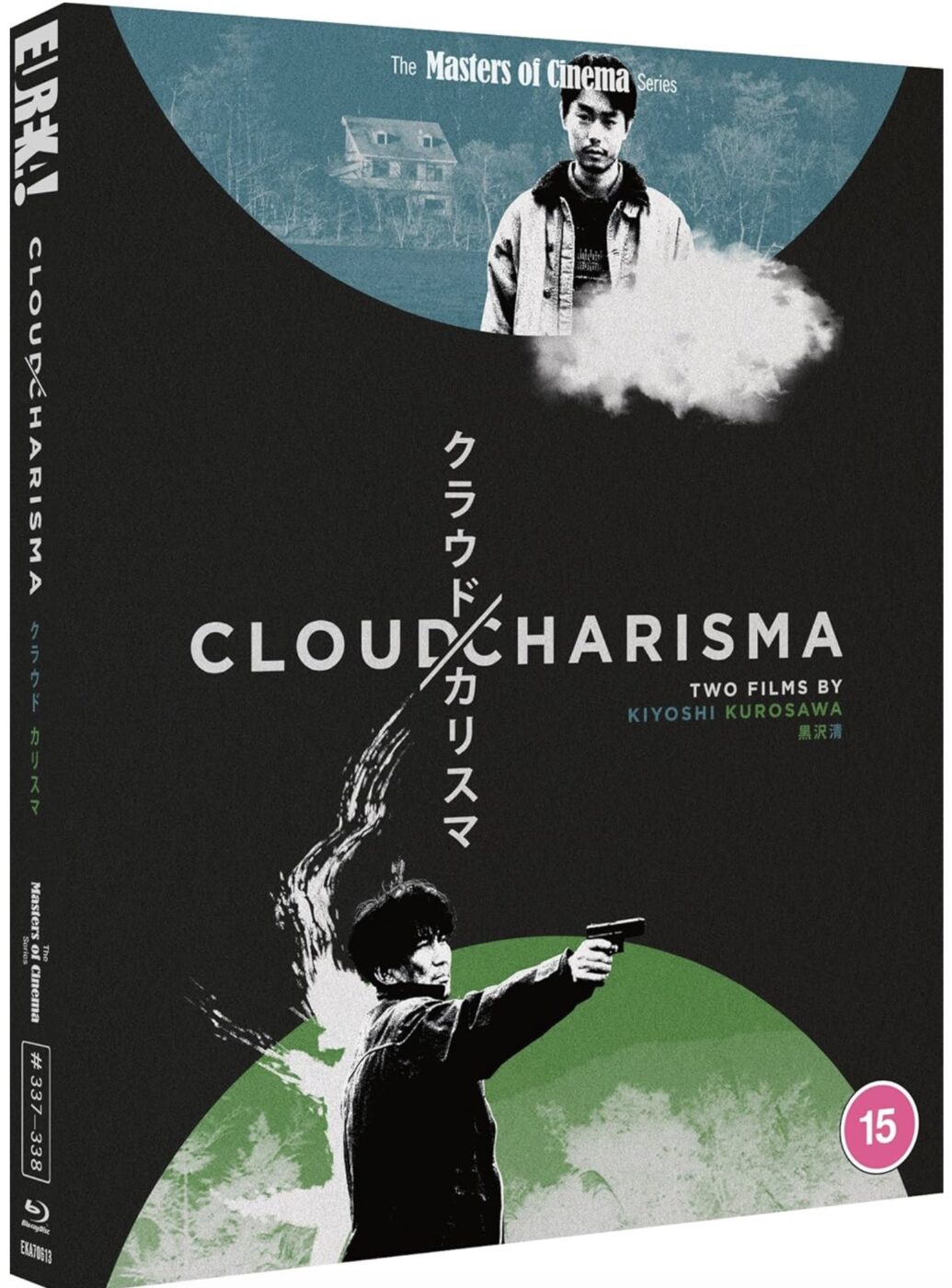

CLOUD (2024) / CHARISMA (1999)

Two films by Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

Two films by Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

It’s difficult to pin down exactly how many features Kiyoshi Kurosawa has written and directed in a career spanning six decades. This uncertainty arises because several of his early works are classified as shorts, and his prolific output includes numerous V-cinema (straight-to-video) releases and television movies. However, fans and critics alike agree that he’s one of Japan’s most influential and perennially inventive genre auteurs—one who deserves to be held in as much esteem as that other Kurosawa.

This new twin-disc Blu-ray addition to Eureka Entertainment’s prestigious Masters of Cinema collection brings together two films made a quarter of a century apart: the mid-career Charisma (1999) and his most recent feature, Cloud (2024). While they are vastly different, they sit well together as bookends to the director’s signature stylistic and thematic obsessions. They won’t be everyone’s idea of fun but, for followers of Kurosawa’s career and those interested in the evolution of Japanese cinema, they offer a challenging yet deeply rewarding experience.

Although he has hopped between genres—ranging from Roman-porno and slashers to yakuza thrillers, crime capers, and supernatural romances—Kurosawa is best known for his creepy, unnerving horror. His superior, noir-styled psychological chiller, Cure (1997), presaged both the found-footage and analogue-horror sub-genres; it remains one of the most haunting entries of Japan’s late-1990s horror boom and was the film that brought him to international attention.

I particularly enjoyed his foray into science fiction with the philosophical alien-invasion thriller Before We Vanish (2017), but I’ve seen relatively few of his films because distribution remains unpredictable outside of Japan and the festival circuit. I was, therefore, delighted to see Charisma finally making its Blu-ray debut alongside Cloud—the latter of which did receive a limited, though brief, theatrical run in the UK.

A seasoned detective is called in to rescue a politician held hostage by a lunatic.

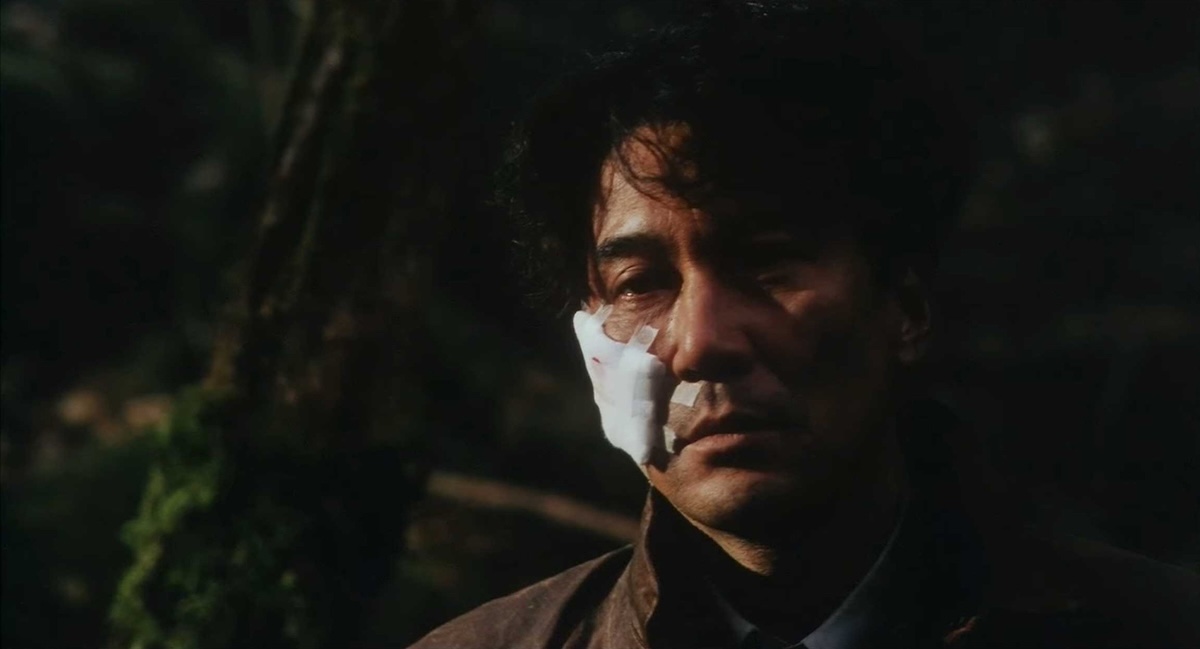

A man sleeping on a bench awakes to the sound of his own name: Yabuike (Kôji Yakusho). The bench is in what we presume to be the dilapidated wing of an old police station; his sleep-deprived state is clearly taking its toll when his superior tells him to take some time off. Not soon enough, however. Before the end of his shift, he’s called to a hostage situation and sent in as a negotiator.

A young man is holding an MP at gunpoint, but Yabuike chooses not to seize the opportunity to resolve the crisis by shooting the captor. Instead, he asks for the young man’s demands. The youth silently hands him a piece of paper bearing the words, “restore the rules of the world,” before executing the hostage and being gunned down by officers. When his superior asks Yabuike why he hesitated when he had a clear shot, he replies: “I wanted to help both of them.” He made a compassionate choice according to his own moral code—one that had terrible consequences.

What keeps Kiyoshi Kurosawa interesting throughout such a long career is how he varies his cinematic approach to suit the narrative, sometimes pivoting styles from scene to scene. From the outset, Charisma is a fine example of his deliberate and meticulous use of visual linguistics.

The opening scenes are shot in a style that aligns with the New Wave cinema of the 1960s, which not only adds a sense of timelessness but subtly guides us to bear witness rather than simply watch. When Yabuike converses with his boss, both men stare toward the camera as they speak, framed within a broad doorway and lit from the side so their faces remain in shadow.

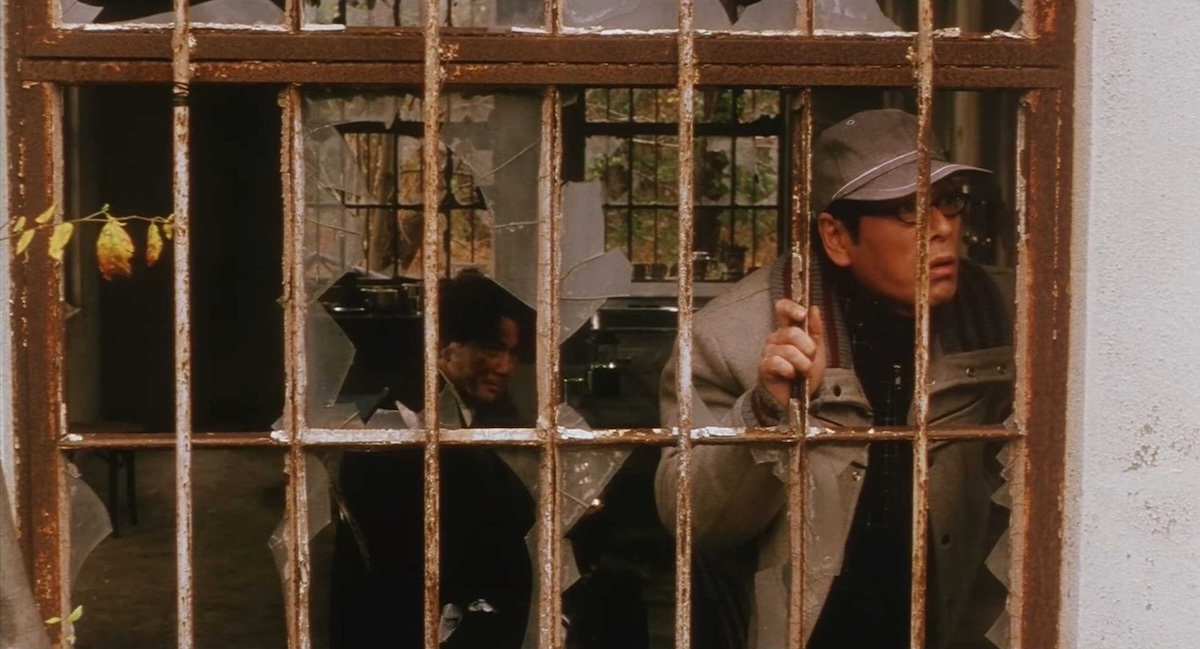

Meeting the viewer’s gaze in this way creates a barrier, preventing the protagonist from becoming our proxy. We’re distanced from him, cast instead as observers. Furthermore, we see the killings of the MP and the hostage-taker from the outside, looking in through a window; this use of “frames within frames” reminds us that the screen is a barrier—a window through which we may only observe. Yet, we soon find ourselves immersed in the dark, dreamlike world laid before us, even if the engagement tends to be cerebral rather than emotional.

Yabuike is eventually dropped at a bus stop on a lonely stretch of road. When the rusting timetable falls off its post, he decides to walk—not along the road, but into the forest, where he soon becomes lost in what proves to be one large, mesmerising metaphor. The slow pacing and “wandering man” motif recall Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984). But whereas Travis (Harry Dean Stanton) sets out to get lost following emotional trauma and a familial breakdown, Yabuike seems to lose himself after a professional failure and the moral collapse he perceives in society.

As night falls, he stumbles across an abandoned car in a clearing and uses it for shelter. In this scene, as in many that follow, Kurosawa uses light and shadow in lieu of traditional editing. Rather than using cut-aways to highlight specific details, he uses light to reveal some elements while darkness obscures others. Those familiar with his work will recognise this as a recurring technique. However, it’s so dark that we can’t be sure what we’re seeing, except for a figure that sets light to the car and, later, another that appears to be dragging the unconscious Yabuike to safety. I must admit, I missed several pertinent points during the first viewing and only caught them on a rewatch—which is obligatory if one wishes to fully appreciate the film.

Scorched and disorientated by day, he finds himself in a liminal part of the forest where a single sickly tree, supported by scaffolding, clings to life. In this cursed woodland, young trees fall at random as roots rot and vegetation withers. A team from the environmental department, led by Nakasone (Ren Ôsugi), is studying the area to find the cause of the dieback; they suspect the lone tree, which appears to be unique. However, a young loner named Kiriyama (Hiroyuki Ikeuchi) is prepared to use violence to defend the tree and keep others away.

We learn that Kiriyama was once a resident of the nearby mental sanatorium. It now stands in ruins, where he cares for the bedridden widow of the hospital’s former director, who imported the foreign tree and named it ‘Charisma’. It was Kiriyama who constructed the supports around the tree, tending it daily in the hope of reviving a plant struggling in an alien environment.

Among the various people the directionless Yabuike stumbles upon are the Jinbo sisters, who live in a comparatively well-appointed cabin. Mitsuko (Jun Fubuki) is a university botanist studying the forest with a particular interest in Charisma. She believes that although it’s a rare specimen, it survives at the cost of the rest of the forest—and therefore a choice must be made.

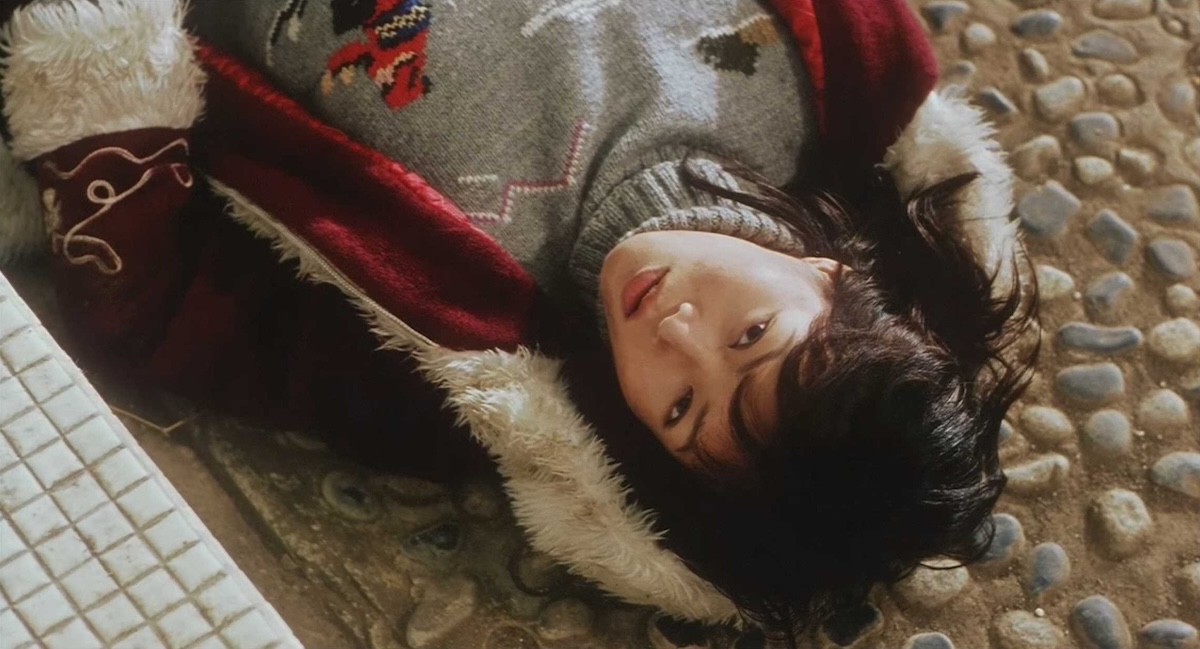

Her younger sister, Chizuru (Yoriko Dôguchi), is sullen and dissatisfied. Feeling trapped by the woods, she initially sees Yabuike as a potential escape route, though she becomes increasingly frustrated by his lack of motivation to find his way home. Both sisters engage in baffling activities: Mitsuko regularly travels to a lakeside well to pour liquid from unmarked canisters, while Chizuru feels compelled to knock large rocks against logs and deadwood.

This seemingly meaningless action foreshadows one of the most disturbing scenes in the movie, when a rogue militia holds down men and executes them with sledgehammer blows to the head. Curiously, their skulls are not crushed into the expected “squelchy mush”. As Charisma reportedly had a respectable budget, this lack of realism isn’t due to a lack of special effects. Is it, therefore, intentionally echoing the rock-on-log metaphor? Are we and the trees one and the same? Is the forest a city?

There is already plenty of symbolism to ponder, and it’s clear that, in narrative terms, the tree is not simply a tree. It operates as a catalyst, much like the ghosts in Kurosawa’s other films. His supernatural forces, psychopaths, and misfits don’t usually perpetrate violence themselves, but rather influence “normal” people to do so by proxy. This seems to be a defining, perhaps unique, trope in J-horror, reminiscent of Ataru Oikawa’s Tomie (1998).

Can Charisma be considered a horror film? In some respects, yes, but the fear is evoked through psychological terror, moral dilemmas, and the existential dread of isolation where “the rules of the world” no longer apply. Human frailty and tenacity in the face of societal collapse are themes that continually fascinate Kurosawa.

Finally, one cannot ignore the theme of the catastrophic impact of the atomic bombs—a physical and psychological legacy that pervades almost every aspect of Japan. Most of the nation’s post-war cinema touches upon this; it would be hard not to. With its poisoned earth, ruined buildings, and various conflicting ideologies, Charisma certainly confronts this legacy. In case you missed the central discussion, it’s made blatantly clear when a second Charisma appears in the forest, towering over the other trees and taking the visual form of a mushroom cloud. Which brings us neatly to the second, very different film in the set…

JAPAN | 1999 | 104 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

A young man who resells goods online finds himself at the centre of a series of mysterious events that put his life at risk.

Ryōsuke Yoshii (Masaki Suda) is desperate to escape his humdrum factory job, even as his supervisor (Yoshiyoshi Arakawa) pushes him towards a leadership role and a pay rise. Instead, Yoshii views his side hustle as an online reseller as a more promising and potentially lucrative pursuit. He certainly seems to have a talent for it; his latest deal—buying a batch of electro-therapy devices cheaply and flipping them on an online platform—earns him enough to quit his job and move to a lakeside house with his girlfriend, Akiko (Kotone Furukawa).

He is more of a high-tech barrow boy than a villain, yet an increasing number of people resent his success. There are disgruntled buyers who feel they’ve paid over the odds for counterfeit goods or gadgets that fail to live up to their outlandish claims. Sôichi Tonoyama (Masaaki Akahori), the supplier of the quack medical devices, can’t help but feel he’s been ripped off. After all, he could have sold them on the internet himself, couldn’t he? But he didn’t; he lacks Yoshii’s know-how, contacts, and insight.

This insight is something Muraoka (Masataka Kubota) hopes to harness when he tries to recruit Yoshii as a partner in an online auction start-up. Yoshii isn’t interested and rebuffs his pleas. In fact, Yoshii seems unable to express much interest in anything, sharing the same ennui found in many of Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s central characters.

The first half of Cloud is slow, arthouse fare that might be boring were it not for the subtle hints of something brewing in the background or lurking in the shadows: a dead rat left outside a door, or a wire stretched across a driveway. This monotony is literally shattered when an unseen attacker hurls part of a car engine through the window of the lakeside house shortly after the couple move in. The incident terrifies Akiko, who begins to long for their old life in their cramped Tokyo apartment.

Yoshii takes on an assistant, Sano (Daiken Okudaira), whom he has known since his school days—a detail that confirms the lakeside area is their hometown. Somehow, this new assistant tracks down those responsible for the attack and ensures they won’t strike again. For such a young and pleasantly mannered man, Sano commands significant fear and respect among the locals; we suspect there’s more to him than he lets on.

This suspicion is proven correct in the second half of the narrative. The film shifts up a gear, evoking Kurosawa’s early yakuza and crime thrillers as the slow-burn suspense explodes into a gritty action climax. It’s reminiscent of the Hong Kong thrillers so beloved by Quentin Tarantino, such as the recently restored City on Fire (1987). The finale is shocking yet superbly executed (pun intended), and the build-up and release of tension is a guaranteed adrenaline rush.

Things escalate when an online discussion group, comprised of dissatisfied loners and losers, fixates on Yoshii—or “Ratel” (Honey Badger), as he’s known by his reseller handle. Blaming him for their own failures, they bond in a virtual arena before a few decide to meet in person to exact hate-fuelled revenge. While this works as a clever thriller plot, it’s also a pointed metaphor for online echo chambers that amplify extremist views until they spill over into real-world violence. Cloud becomes a highly relevant examination of the moral and psychological ruin caused by isolation and media manipulation.

Though I couldn’t disagree more, I’ve read reviews that praise the arthouse pretensions of the first half while decrying the descent into visceral gunplay. Kurosawa has explained that his primary motivation for Cloud was a desire to make an action film featuring realistic, everyday people. He describes his writing technique as starting with a genre idea and grounding it in believable situations, citing Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs (1971) as major influences. I also detect a touch of Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and even a hint of Andrei Tarkovsky. It is a truly fascinating mixed bag.

JAPAN | 2024 | 124 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

writer & director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

starring: Koji Yakusho, Hiroyuki Ikeuchi, Jun Fubuki, Yoriko Doguchi, Ren Osugi, Yutaka Matsushig & Akira Otaka (Charisma) • Masaki Suda, Kotone Furukawa, As Akiko, Daiken Okudaira, Amane Okayama, Yoshiyoshi Arakawa, Masataka Kubota & Masaaki Akahori (Cloud).