THE CHILD (2005)

Bruno and Sonia, a young couple living off her benefit and the thefts committed by his gang, have a new source of money: their newborn son.

Bruno and Sonia, a young couple living off her benefit and the thefts committed by his gang, have a new source of money: their newborn son.

A young couple are attempting to navigate the hardships of raising a newborn baby in poverty. Wandering aimlessly through city streets by day and sleeping in homeless shelters by night, under the mother’s care the baby has all its needs fulfilled. While she’s briefly absent and it’s the father’s turn to look after its welfare, he has it sold within the hour. This is not a crappy joke about the differences in parenting skills between fathers and mothers, but the setup of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne’s The Child / L’Enfant.

The sale is a sickening moment that forms a pit in your stomach and has you on the edge of your seat for every second afterwards, praying that it will be resolved. Thankfully, it avoids the cruellest possible fate for these protagonists, but that doesn’t mean that they won’t be put through the wringer across this 95-minute film. Like many of the Dardenne Brothers’ movies, it focuses on disaffected people forced to confront their bleak lives in a world that’s blind to their woes. Young parents Bruno (Jérémie Renier) and Sonia (Déborah François) might receive regular social security cheques, but their living circumstances are far from ideal.

In fairness, that’s not exactly anyone else’s fault. Bruno consistently takes the easy way out, refusing to work and squandering his money, with his supplementary income as the leader of a trio of thieves (consisting of him and two pre-teens) slipping out of his hands not long after he pawns the items he steals. Over the course of The Child, Bruno is forced to reckon with what is most important in life, and how he can navigate a world where one’s fortunes can suddenly decline at a rapid rate. Renier is a marvel as the 20-year-old protagonist, where he’s just kind enough in his interactions with others to make it impossible to hate him. He’s also a boy masquerading as a man, too caught up in fleeting thrills, reckless spending, and joblessness to consider that bringing a child into this world requires some degree of responsibility.

The Dardenne Brothers are fantastic at making their storytelling worlds feel lived-in without focusing on anyone besides their main characters. Most filmmakers attempting to capture the pulse of a region or socio-economic environment would explore the people hanging on the peripheries of both these societies and the main characters’ lives. It’s an effective technique to draw us into these worlds and what defines them, but the precision with which these directors explore their protagonists’ circumstances does more than enough to lend authenticity to their experiences. You feel that Bruno and Sonia have a shared history together from the outset, while The Child‘s earnest depictions of their bleak living conditions and desire for a better life allow you to imagine a future for the pair after the end credits have rolled.

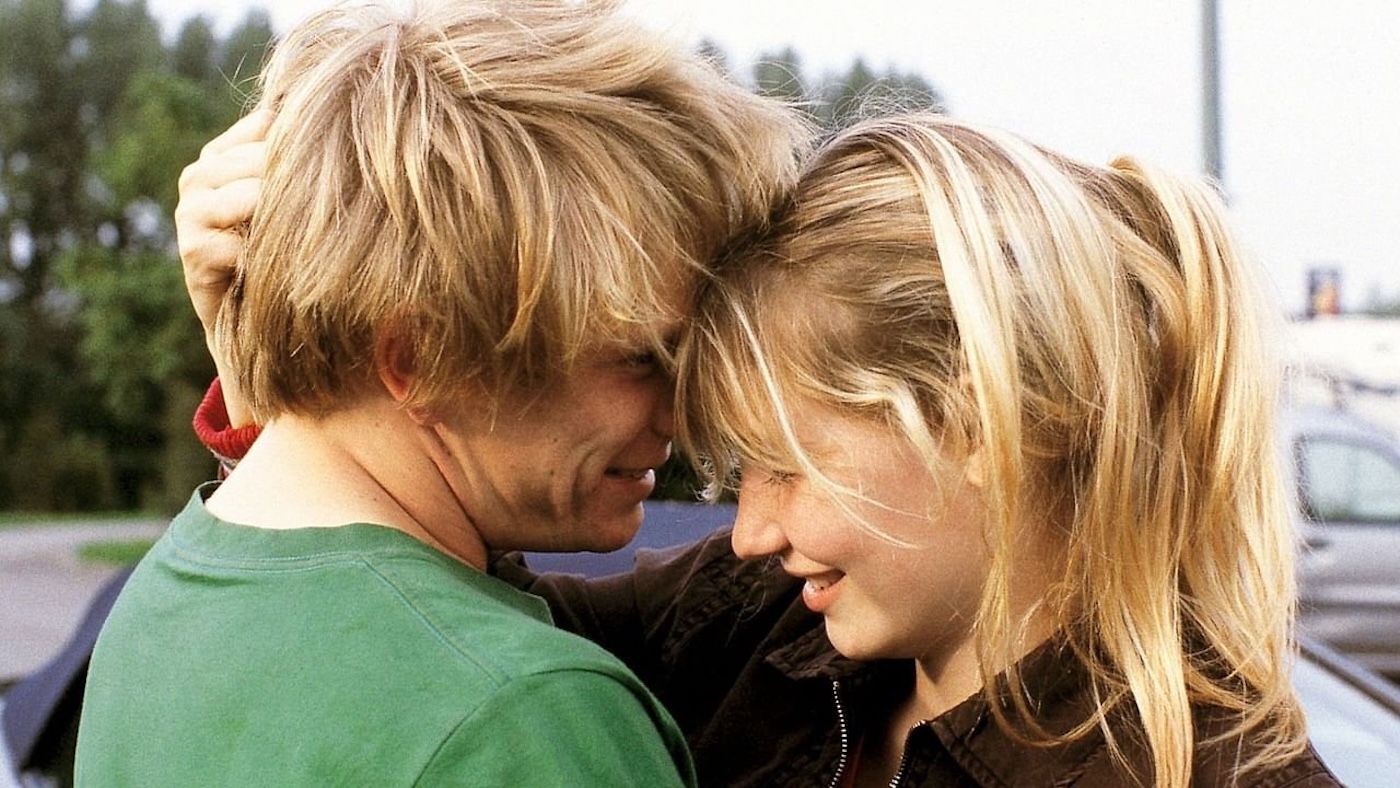

The only snag in the brothers’ relentlessly empathetic approach here is that the benevolent interactions between this young couple lack any richness. They laugh and joke around, with Sonia tripping up Bruno in one scene and spraying her drink over his head in another, while he chases after her and their play-fighting ends in an embrace. These happy moments are a good reminder that the pair are really just wayward children trying to navigate a world far too tough for them to handle, but there’s something rather inane about these scenes’ one-note antics. It’s enthralling watching Bruno and Sonia as two desperate people navigating the hardships of everyday life, but as characters madly in love with one another there’s something missing from this tragic experience. It takes Bruno’s unbelievably thoughtless, callous error to kickstart both the film’s plot and its ability to become truly absorbing, whereby the dramatic urgency is raised to such a degree that it hardly matters that the pair’s relationship dynamics felt a tad scattershot.

Bruno wanted to be rid of responsibility, with the decision that results from this thought process having the unfortunate effect of saddling him with more of it than he’s ever had to reckon with, all bound together by moral dilemmas that will surely lead to ruin. What is most striking to me about French cinema is how eagerly it champions unlikely protagonists. There’s the bitterly vengeful maid in Claude Chabrol’s La Cérémonie (1995), the petty criminals in Jacques Audiard’s urban crime films, and the negligent, reckless, irresponsible Bruno in The Child. Some of these films inspire only pity, while in the case of The Child you’ll find yourself rooting for this lost soul in spite of his flaws. The central question of these films isn’t whether or not such characters can change—even if that is an essential part of these dramas—but whether the world will allow them to do so.

Even if The Child takes its time to transform into a compelling drama, the end result is achieved so masterfully that its early missteps hardly bear commenting on. The final 20 minutes of this film are phenomenal, with hair-raising tension to get your blood pumping and your heart pounding like a drum, begging for some kind of release from this anxiety that ensnares the viewer and Bruno. Attempting to do the right thing has just about destroyed this young man’s spirit, forcing him to act as the kind of man he’d been attempting to transcend in the first place. Even if his loutish and irresponsible behaviour is guaranteed to rankle viewers, it’s impossible not to pity Bruno, whose misfortunes are portrayed so seamlessly by the Dardennes that The Child never feels preachy or unfairly cruel.

The pair are excellent writers, but it’s their directing that remains under-appreciated. The camera usually stays unbearably close to these characters, especially as Bruno heads upstairs in a futile attempt to enter Sonia’s flat, trying to become a better man, ambling on helplessly. The camera teeters uncertainly, refusing to take a cold, clinical look at this protagonist. He isn’t the subject of an exercise in despair, but an organic part of this world that is capable of change. There’s always hope amidst the darkness, and always humanity present in the wake of tragic circumstances.

The camera movements and dedication to tracking Bruno’s every moment match this uncertainty, an undulating rhythm that maps onto this protagonist’s shifting tides of luck and fortune. It never feels as if we observe Bruno from a distance. It’s as if we’re right there, experiencing the dilemma first-hand. And for The Child’s spectacular final stretch, you can momentarily forget that anything has ever existed beyond this dilemma. Refusing to drown their protagonists in endless streams of sorrow when there are more genuine ways of conveying the brutal pangs of slice-of-life cinema, the Dardennes opt instead to drown you in these characters’ lives. So long as you trust the prolific brothers to never give in to misanthropy, they trust you to recognise that they are never trying to be cruel or contrived, only precise. With this thought lurking in the back of one’s mind, most often expressed as appreciation for their endless reserves of empathy for these characters, it’s always a pleasure to observe a new film of theirs and dive right into these difficult, but never hopeless, lives.

BELGIUM • FRANCE | 2005 | 91 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH

writers & directors: Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne.

starring: Jérémie Renier, Déborah François, Jérémie Segard, Fabrizio Rongione & Olivier Gourmet.