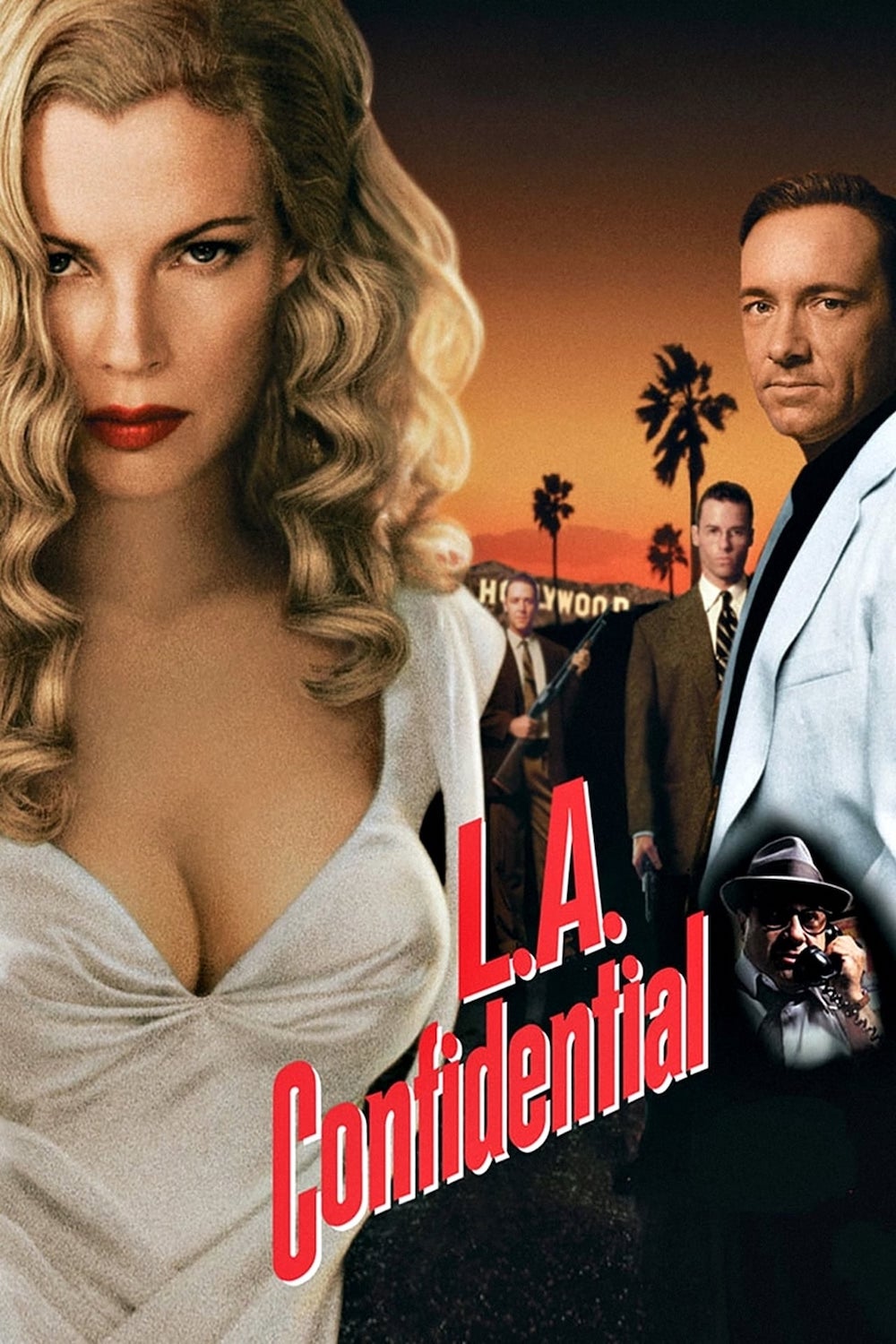

L.A. CONFIDENTIAL (1997)

In 1950s Los Angeles, three officers from a corrupt police department approach the same crime in very different ways.

In 1950s Los Angeles, three officers from a corrupt police department approach the same crime in very different ways.

Richly textured, sprawlingly plotted, and some 500 pages long, James Ellroy’s 1990 novel L.A. Confidential was never going to translate to the screen directly. But Ellroy’s brand of lean, scorching-hot film noir was successfully reimagined for film by the slightly unexpected duo of director Curtis Hanson and co-writer Brian Helgeland—neither of whom gained much critical applause in their earlier careers—and brought to life by an outstanding ensemble cast, perhaps the film’s single greatest strength, in which the smallest roles often adedd as much as the biggest.

As trimmed down from Ellroy’s original by Hanson and Helgeland, L.A. Confidential begins at Christmas 1952 and mostly takes place in 1953, the year of Raymond Chandler’s Long Goodbye. An early scene of Los Angeles Police Department officers beating up Mexicans, and the subsequent cover-up, serve as confirmation that though L.A. Confidential can’t escape charges of nostalgia to a degree, it’s certainly not rose-tinted nostalgia. This episode also introduces us to the three cops at the core of the story.

In the fallout of the scandal, dapper Jack Vincennes (Kevin Spacey) is transferred to the vice unit, angry Bud White (Russell Crowe) is given an off-the-books assignment as muscle for dubiously legal “law enforcement” activities, and bespectacled, proper Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) is promoted.

Nominally, the bulk of the movie then follows these three men as they investigate a multiple shooting at the Nite Owl coffee shop, in different ways and for different reasons, where the horror of bodies piled up in the men’s room reaffirms that while L.A. Confidential is loving in its recreation of period Los Angeles, it harbours no more illusions about its subject’s lovability than Ellroy did.

As they delve into the crime they encounter sleaze and corruption on a wider and wider scale, some of it already known to them—for example, the way the gossip journalist Sid Hudgens (Danny DeVito) deliberately sets up celebrities to commit crimes and give him juicy stories—-and some of it more surprising, such as the stable of high-class call girls kept by Pierce Patchett (David Strathairn) and surgically altered to look like Hollywood stars.

And over everything looms the avuncular and ambiguous figure of the police department’s Captain Dudley Smith (James Cromwell). There’s no doubt from the beginning that his ethics are flexible (“the department needs smart men like Exley, and direct men like you”, he tells White—“direct” being a euphemism for “law-breaking”), though exactly what his real agenda might be is an undiscussed mystery for a long time.

But the plot, in a narrow sense, isn’t really what matters here: L.A. Confidential is essentially about the city and the era, and what matters is the way it reveals the corruption at the heart of Los Angeles, a persistent theme in Ellroy’s work, through the interlocking stories of a large cast of exceptionally well-realised characters.

Barely a single individual is without sin, though not all are dominated by it. For example, Exley and White both have family tragedies in their pasts that motivated them to sign up as cops, even if (in White’s case) that doesn’t excuse his persistent stepping over the boundaries. But Vincennes, when asked why he joined the force, replies—after a long, rueful silence—“I don’t remember”. At that moment the film not only pinpoints his lack of moral anchor compared to his colleagues, but also hints that he is aware of it, and not entirely comfortable with it.

Exploitation and lies are everywhere. The metaphor of prostitutes transformed under the knife to look like stars makes an obvious point about Hollywood in general (though Kim Basinger’s Lynn Bracken, the major female character in the mostly male-driven L.A. Confidential, claims her resemblance to Veronica Lake is natural), as does the fate of one unfortunate male actor.

The media is shown as disconnected from the truth: Hudgens’s magazine Hush-Hush (based on the real 1950s periodical Confidential) is about as trustworthy as today’s Weekly World News, while the TV cop show Badge of Honor (based on Dragnet)— for which Vincennes is a consultant, something he seems to value more than his actual police work—portrays a wholesome police force far removed from the reality in which White, Exley and Vincennes operate.

Broader issues in the city form part of L.A. Confidential’s underpinning, too. Patchett is investing in the construction of the Santa Monica Freeway, one of the road arteries that would soon transform Los Angeles. Racism is endemic and de facto racial segregation is accepted.

The resonance of these ideas gives L.A. Confidential much of its cumulative impact, but it’s definitely not just a film of ideas. Individual sequences are often singularly powerful, perhaps the most notable being three simultaneous suspect interviews conducted at a police station by Exley, with his fellow officers watching through one-way glass.

The interviews culminate with an intrusion by White that typifies how different his aggressive approach to policing is from Exley’s more by-the-book technique— while also making it clear (as many less thoughtful movies wouldn’t) that for all that he’s an irritating prig, Exley’s methods do work. Just as the line between law-abiding and criminal is not in practice universally agreed on here, nor is the line between effective and ineffective police work. (At another point, after White has shot an unarmed suspect, Exley asks damningly how it will look in the official report; “it’ll look like justice”, says White.)

While these interviews are of course focused on dialogue, the rescue of a kidnapped young woman from a house in a Black district is a more action-led highlight, expertly and tensely paced, even if it’s a valid criticism that just occasionally L.A. Confidential’s reluctance to hang around combined with its convoluted storyline can create a little confusion.

In a cast where almost every role has something worthwhile to add, Pearce’s Exley and Crowe’s White have the most clear-cut character arcs. Crowe’s performance, while thoroughly convincing, is of a kind we’ve seen from him again since, so it may be the less famous Pearce’s that really stands out these days. His upright Exley seems at first to be an ineffectual cliché, but in his own way turns out to be just as conniving as his less rigid colleagues.

Spacey, meanwhile, creates in Vincennes a man who is corrupt and vain to a degree that is chilling, and whose affability is clearly not to be trusted (even if nowadays it may not be easy to distinguish one’s knowledge of the man from one’s reaction to his performance, he’s still superb).

In smaller but still key parts, Strathairn is wonderful as the politely unfriendly, possibly ruthless Patchett, while DeVito’s fast-talking journalist Hudgens (he even speaks in tabloidese, licking his lips at the prospect of “prime sinnuendo”) is a delight. John Mahon as the police chief and Gwenda Deacon as the eccentric mother of a Nite Owl victim grab the attention, too, but perhaps the best of the whole lot is Cromwell’s Captain Smith: this actor, so consistently fine over so many movies, keeps us guessing all the way and rather liking “Dud” even after we’ve started to wonder if we ought to.

The cast, collectively, is the greatest asset of L.A. Confidential. But the inanimate contributes much to its intense sense of place too. Many of the Los Angeles locations are fascinating in themselves (not least the architect Richard Neutra’s Lovell House, standing in for Patchett’s residence), while the brown-green palette (along with a more feminine cream for interiors at Lynn Bracken’s home) reminds us that this isn’t the high-tech and optimistic 1950s but the final gasp of an earlier, more old-fashioned period.

Even scenes where the setting itself isn’t particularly notable are often built around a strong physicality which does much to enhance the impression that these people are in a real place. For example, the moment that we see White driving away from a motel, his car framed by two of the small oil wells that littered L.A., pumping away through the night. The city has a life of its own.

Perhaps the best of them all, though, is the scene where a gangster is assassinated at home. A cushion falls, a glass window collapses seconds after the shots ring out, and people are only marginally in the frames. The presence of recognisable actors sometimes requires suspension of disbelief, but here it’s difficult not to believe that the gunfire broke the glass.

L.A. Confidential was not only a box office success but almost universally acclaimed too. Philip French in The Observer called it “one of the great movies” about Los Angeles and Hanson’s best, mentioning “perfect” casting and performances, as did many critics.

The writers and Basinger both won Academy Awards—a little oddly in the latter case given that her performance, while interesting and persuasive, is not the movie’s most impressive —and L.A. Confidential was nominated in many of the other most important Oscar categories, including ‘Best Picture’ and ‘Best Director’.

25 years later, not only has it not dated a bit, but its questioning of the violent, rapacious reality beneath the dream seems if anything even more relevant than it was in 1997. It might not quite have the “wow” factor of Ellroy’s book, but it surely comes as close to recreating the writer’s world as any movie could.

USA | 1997 | 138 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Curtis Hanson.

writers: Brian Helgeland & Curtis Hanson (based on the novel by James Ellroy).

starring: Kevin Spacey, Russell Crowe, Guy Pearce, James Cromwell, Kim Basinger & Danny DeVito.