BRIGHTON ROCK (1948)

After murdering a journalist, a young gangster in 1930s England discovers a potentially fatal flaw in his alibi...

After murdering a journalist, a young gangster in 1930s England discovers a potentially fatal flaw in his alibi...

The first sentence of Graham Greene’s 1938 novel Brighton Rock is surely its most famous: “Hale knew, before he had been in Brighton three hours, that they meant to murder him.” There, as well as asserting how important Brighton itself will be to his tale, Greene sets the tone of violence and inescapable doom… provides a foretaste of how fast-moving and to-the-point his narrative will be… and establishes a vivid sense of the character Hale being all alone with his terrible knowledge.

That sense is well captured in John Boulting’s film, and so is everything else about Greene’s first line and indeed most of his novel. Despite a famously weaker ending (more of which below), it’s faithful in sense and mood if not every tiny detail to its literary source.

Greene himself had come in as screenwriter after dissatisfaction with the original screenplay from playwright Terence Rattigan. The latter was becoming a major name at this time—indeed, his play The Winslow Boy would be released as a film in the same year as Brighton Rock—but despite some wartime experience he’d not had much involvement with the movies. Greene, by contrast, had worked as a cinema critic as well as on several films, and had already had half a dozen of his novels adapted for the screen by others, starting with Orient Express (1934).

If Rattigan’s script for Brighton Rock was rejected for being too nice, Greene’s could certainly not be accused of that: nastiness pervades and even the few sweeter moments are soured by knowledge of what is going on in the background, or likely to come next.

The setting of the film is Brighton, a large seaside resort on the southern coast of England, in the mid-1930s. After brief opening titles promising us that the crime-ridden Brighton of the period between the wars is “now happily no more” (perhaps a sop to the locals in whose town much of it was filmed?), Brighton Rock gets promptly to its first death with a newspaper announcing that the body of a Brighton gangster called Kite has been found.

This is followed quickly by the next development, also featuring a newspaper (Greene was a former newspaperman, too): we see a news vendor’s trolley promoting a visit to Brighton by ‘Kolley Kibber’ of the Daily Messenger. Readers who find one of the cards ‘Kibber’ leaves around the town can win a prize, and anyone who identifies him in person can win a bigger one.

Such promotional stunts were common at the time, but the importance of this one to Brighton Rock is that ‘Kibber’ is in fact journalist Fred Hale (Alan Wheatley), the ill-fated Hale of the novel’s opening sentence… and that after Hale’s reporting exposing Brighton’s crime scene, one of the town’s gangs is determined to kill him.

The small gang, led by Pinkie (Richard Attenborough), soon corners Hale and dispatches him, after a high-tension sequence of pursuit and evasion where both Hale’s terror and his killers’ complete ruthlessness is palpable. But the murder of Hale is only a precursor to the main story of Brighton Rock, and this hangs upon a single, difficult-to-foresee mistake made by the gang.

Pinkie has ordered one of its member, Spicer (Wylie Watson), to impersonate Hale for a few hours after his death and continue distributing the promotional cards around town, hoping that the police will believe Hale was alive later than he actually was, allowing the gang to establish secure alibis.

But Spicer leaves one of the cards in a café, where the waitress Rose (Carol Marsh) realises it wasn’t Hale she served. “I’ve got a memory for faces,” she says, unwittingly setting in train the rest of the storyline.

Pinkie, realising his gang’s alibis might collapse if the police realise someone was impersonating Hale, befriends Rose and eventually proposes marriage to her, in order to remove her as a potential witness—a wife could not incriminate her husband in court under English law. She’s flattered by the attentions of this seemingly sophisticated young man, and falls for him, but secretly he loathes her.

At the same time, Pinkie also has other problems to deal with: a larger, rival gang led by Colleoni (Charles Goldner) is seeking to take over Brighton, and small-time entertainer Ida (Hermione Baddeley), who briefly encountered Hale in his final hours, is becoming suspicious he was murdered.

It’s all carefully constructed to lead to tragedy, and lends itself well to the medium of cinema—-unsurprisingly, since although his novel as published took on some of the weighty Catholic themes which so preoccupied Greene, he had originally intended it as simply a crime story suitable for movie adaptation.

If it has a narrative flaw, it’s that Ida seems to grasp things more quickly than seems plausible, given she starts off completely unaware of the people and issues involved. But that, of course, is necessary to move matters along.

Many people also find fault with the ending, changed to please the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC). Not to give too much away, it alters what should have been a devastating revelation of Pinkie’s hatred for Rose—the mechanism for which was set up in an earlier, uncut scene—into something much more ambiguous. But though it is undeniably less impactful than the book’s final words, it’s still far from being a happy ending, and it still leaves open the possibility that what the book describes will happen in the future, after the film has finished.

It’s weak but not seriously damaging to the movie; if anything, the odd final shot of a crucifix is less of a satisfactory conclusion than the scene as a whole.

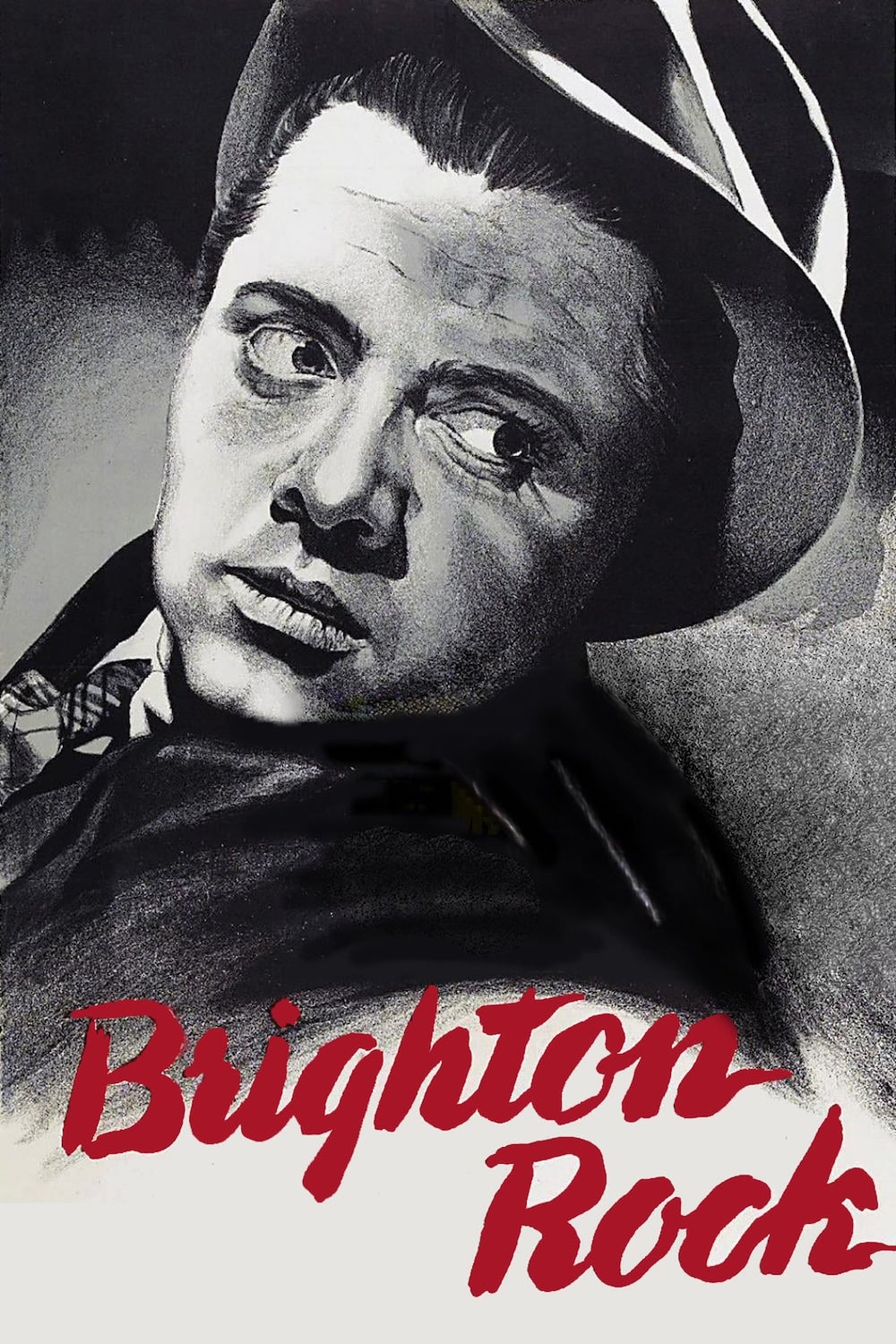

Though he does not appear in this final scene, Attenborough’s Pinkie dominates the film (and everyone’s memory of it); albeit slightly overacted by modern standards, this is the standout among the actor’s earlier roles and Pinkie is an unforgettable creation, somewhat foreshadowing Attenborough’s chilling serial killer in 10 Rillington Place (1971).

Throughout the film, Boulting and cinematographer Harry Waxman frequently place his face in half-shadow (often aided by Pinkie’s trilby), but while Pinkie certainly has psychopathic aspects he is not just evil. He is also insecure, to the point that one can almost (not quite) feel a little sympathy for him, and Attenborough portrays the young criminal as tense, coiled, anxious, constantly fiddling with the cat’s cradle that we see even before his face in his very first scene.

Pinkie is increasingly suspicious as Brighton Rock progresses, and joyless too (he doesn’t smoke, drink, or even eat chocolate, and seems uninterested in sex). Mostly he seems driven by fear (he says he wants security, not love, and at one point he speaks of a “suicide pax”, erroneously believing the phrase refers to suicide giving a person peace). His only pleasure seems to be in mild sadism: when his gang turns up at the home of a bookie (Harry Ross) to shake him down, and the unfortunate man says his wife is sick and not sleeping, Pinkie repeatedly rings the doorbell with a deliberate, determined, almost entitled expression.

Attenborough was 24 when the film was released, a significant difference from Pinkie’s supposed 17, which makes him not quite credible as a teenager. That doesn’t matter as much as it could, though, because the narrative doesn’t specifically call for Pinkie to be that age, simply that he be not as experienced in the world—or as confident—as he would like to pretend.

Much the same applies to Rose, with Marsh again being a few years older than her teenage part. If she’s less memorable than Pinkie, that’s an inevitable result of the role, which requires her to be primarily an innocent victim rather than a character with active agency. But given that limitation Marsh creates a believable, and sad, young woman.

Baddeley’s Ida is as different as could be: brassy, often tipsy, eccentric (she fancies herself a psychic) but sharp. Greene didn’t like the character herself, saying he felt Ida “refused to come alive”, but viewing the film today she does more than come alive: she comes close to dominating her scenes.

In smaller roles, meanwhile, Goldner as Colleoni is also very credible, as are the three members of Pinkie’s gang, all different in their approach to their leader but none of them truly fond of him, and none of them as wicked either: Watson as Spicer, Nigel Stock, and William Hartnell (later the first Doctor Who). More striking than any of these three, though also perhaps more exaggerated, is Harcourt Williams as Pinkie’s lawyer Prewitt: an elderly, seedy, rueful man who says “I’ve sunk so deep, I carry the secrets of a sewer”.

Brighton itself is a character, too, as much as Vienna would be in the next important Greene adaptation, Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), which is the best of all, though Brighton Rock certainly belongs in the upper echelon.

Greene acknowledged his Brighton was partially imaginary rather than a faithful portrait of the town in the 1930s. Nevertheless, much of it—from the opening montage of deckchairs and picknickers to the racecourse bookmakers in a later scene—has the feel of verité, and from the very first line of the movie the copious underworld slang also provides an air of authenticity, regardless of how accurate it might or might not actually be: to “lace someone up” is to knife them, a “brass” is a woman, a “bogey” a policeman, and so on. (Translating the title phrase proved difficult, though, and Brighton Rock—referring to a kind of candy, not geology—ended up in Austria as Dark Alleys, in France as The Gang of Killers, in Brazil as The Worst of Sins, and in the USA rather imaginatively as Young Scarface.)

Perhaps unexpectedly, given both the grimness of its storyline and its thematic concern with sin and damnation, Brighton Rock also has moments of delicious dark humour: the hawker selling razor blades (the hoodlums’ weapon of choice), a brilliant moment where Pinkie unexpectedly appears next to Hale on a funfair ride called Dante’s Inferno, the religious proselytiser parading at the races with a board proclaiming ‘THE WAGES OF SIN IS DEATH’ while eating a worldly sandwich.

Brighton Rock has precious few weak points, indeed, although the unimaginative score by Austrian émigré composer Hans May is one of them. At the time of its release, outcry over its unflinching (for the time) portrayal of brutal violence and its focus on criminals (law enforcement barely appears) often overshadowed its merits as a movie, but to modern eyes these are no longer issues and it’s now rightly regarded as one of the finest British films of its period.

A 2011 remake by Rowan Joffé, moving the action to the 1960s but retaining the essence of Greene’s story, was a box office flop and has largely been forgotten. It’s not terrible but adds nothing of great interest to Boulting’s version. That may partly be because Attenborough (later to be more successful as a director than as an actor) permanently defined the role of Pinkie, but it’s also because Brighton Rock—rather like Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960)—is one of those films which really doesn’t need anything changing.

It’s relatively small in scale, rather modest in its aspirations to tell a strong tale well while hinting at some more universal issues beyond, and completely devoid of pretension. From the very beginning, when Hale realises he is going to die, it’s clear what kind of movie we are going to get… and Brighton Rock never disappoints in delivering.

UK | 1948 | 92 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: John Boulting.

writers: Graham Greene & Terence Rattigan (based on the novel by Graham Greene).

starring: Richard Attenborough, Hermione Baddeley, Carol Marsh, William Hartnell & Harcourt Williams.