THE BOOK OF CLARENCE (2023)

Struggling to find a better life, Clarence is captivated by the power of the rising Messiah and soon risks everything to carve a path to a divine existence.

Struggling to find a better life, Clarence is captivated by the power of the rising Messiah and soon risks everything to carve a path to a divine existence.

The Book of Clarence is a startlingly religious film. And it comes from a director, Jeymes Samuel (The Harder They Fall), who clearly fears God and sees Jesus as a subversive figure whose power lay in undermining imperial Roman rule. Samuel takes this idea—that Jesus was a rebel–and pushes it to its extremes, perhaps even too far.

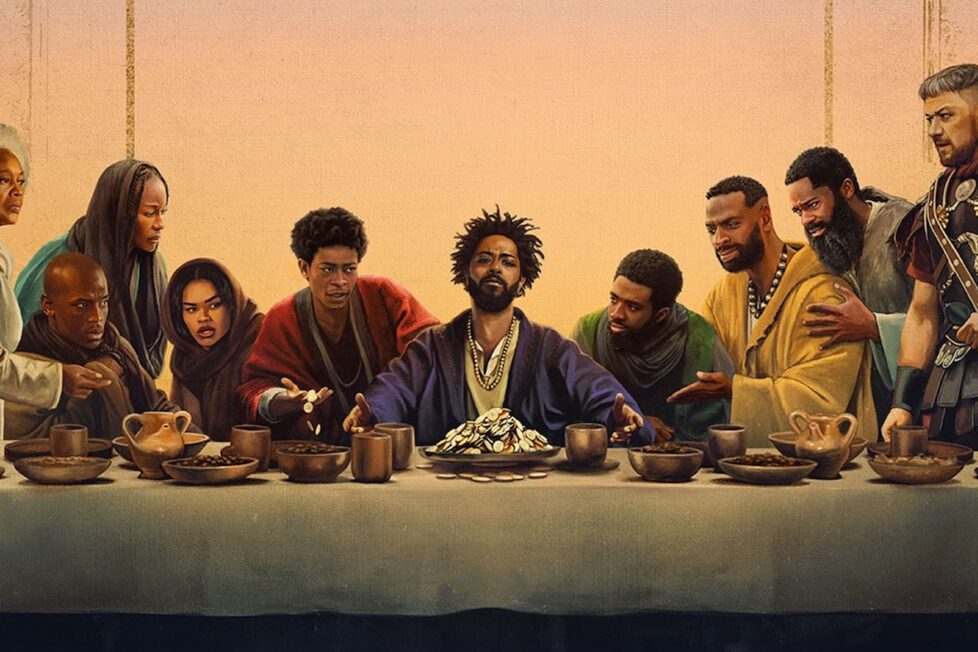

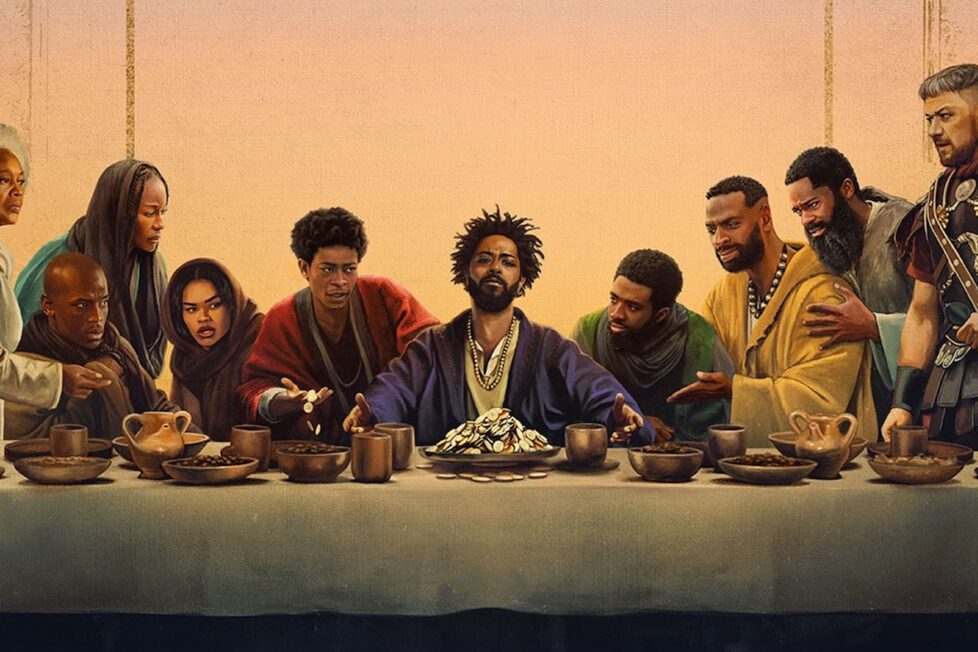

The film reimagines the fictional “13th Apostle” Clarence (LaKeith Stanfield) in a farcical exploration of his attempts to become a Christian figure. Yet, like its titular character, the film overreaches in its attempt to be clever, its focus on subversion often obscuring its own deeper message and leaving viewers wondering what it all means.

Clarence, Jerusalem’s resident mischief maker, can’t seem to stay out of trouble: selling a near-identical weed substitute, snatching coats from the city’s downtrodden, and brazenly taunting Roman guards. Unfortunately, his latest con lands him in hot water with Jedediah the Terrible, Jerusalem’s top mafioso. This is hardly unfamiliar territory for Clarence. Another poorly hatched scheme has gone belly up, demanding yet another ingenious (and inevitably chaotic) solution. Down the rabbit hole we tumble a trail of fresh turmoil marking his descent.

Facing a potentially fatal encounter with Jedediah, Clarence hatches a desperate plan: ingratiate himself with Jesus and the apostles for protection. The good news is that Clarence is the twin brother of Thomas the Apostle. The bad news is that Thomas, a supposedly pious man, has turned his back on his family and is glad to remind Clarence of how small his position in life has become.

The lack of weight to this central tension, where Clarence struggles to get help from his reluctant brother, significantly weakens the plot’s overall impact. While it explains Clarence’s need to constantly fix problems, those problems carry little consequence and feel safe and inconsequential.

Instead of focusing solely on Clarence’s escape from Jedediah, The Book of Clarence delves deeper into the evolution of his relationship with faith. While this is a valid artistic choice, it creates a nagging tension regarding the film’s identity. Does it yearn to be a character study or an adventure film? Is it a character study or an adventure film? There’s never a solid answer. The movie is moody, not committing to either thread and so leaves both underwhelming.

Additionally, the potentially interesting duality between Clarence and his brother Thomas in terms of healthy religious values remains curiously unexplored, further contributing to the film’s unfulfilled potential.

During the lengthy runtime, Clarence decides to become a Messiah, attracted by the potential financial gain. He attracts followers, each joining his cause with varying degrees of doubt. Omar Sy (Lupin) excels as the strongman Barabbas, imbuing scenes with gravitas even when the action sequences lack urgency. He’s one of the few characters whose past ignites genuine curiosity. Marianne Jean-Baptiste portrays Clarence’s mother, infusing her earnest lines with genuine warmth.

In stark contrast, Clarence’s sidekick Elijah (RJ Cyler) feels like a misjudged role. Although the film expects us to care about him, it offers few impactful moments that truly earn our empathy. Instead, we’re bombarded with endless attempts at humour through Elijah’s antics, primarily revolving around his persistent marijuana use—smoking, lighting, or awkwardly hiding joints. Sadly, none of these gags resonated with my audience, resulting in a complete absence of laughter during his scenes.

Elijah’s connection to Mary Magdalene (Teyana Taylor) is equally thin. This subplot, if it deserves that label at all, feels less like an enriching inclusion and more like a wink to the writer’s biblical expertise. Much of the film follows this pattern, endlessly and gratuitously indulging in biblical references that lack relevance to the narrative.

While I trust LaKeith Stanfield’s taste in screenplays, The Book of Clarence, though aiming for importance, falters under its own weight. The ambling plot and overly deferential script towards religion hold back its subversive ambitions. Fearful of truly shocking swings, it loses its punch in crafting a fresh Messiah origin story. Stanfield is, as always, captivating—I’d watch him watch paint dry—but even his undeniable charisma can’t overcome my overall disappointment.

Despite its flaws, I can understand why Stanfield signed on. Writer, director, and composer Jeymes Samuel has a unique vision and collaborates with cinematographer Rob Hardy to stunning effect. They deliver a curiously captivating film with genuinely fresh cinematic sensibilities. It’s a feast for the eyes, bathed in the rust and ochre hues of ancient landscapes, captured from hyper-modern, near-hallucinatory angles. Magical realism permeates the narrative. Ideas manifest as floating light bulbs, characters levitate with nonchalance, and fantastical elements unfold as naturally as in any religious text. These bold choices harmonize with the disorienting camerawork, creating a potent cocktail of the familiar and the otherworldly. While a few scenes echo classic religious cinema, The Book of Clarence ultimately crafts a novel visual tapestry, a testament to Samuel’s subversive ambitions.

Granted, there’s also intriguing discourse to be explored regarding the film’s central theme of knowledge versus belief. This is the sole concept that almost unifies the meandering plot and character arcs of The Book of Clarence.

Clarence is consumed by a thirst for knowledge, while the apostles and his brother Thomas find solace in faith. Samuel wrestles with the question of what’s more effective—knowledge or belief—a question mirrored in the film’s stylistic choices, from its disorienting camera angles to the images of floating men. This religious exploration lies at the core of the film’s intentions: it wants to delve into the power of faith and the transformative potential of conversion. The ending offers genuinely interesting insights here, adding another layer to this complex cinematic meditation.

The reimagining of John the Baptist as a dutiful grump tickles my imagination, making me wonder if I’m missing a deeper layer. Perhaps had I been a more devout Sunday School attendee, the subtle allusions to characters like Jezebel would have resonated and ignited a sense of playful inspiration. Yet, even with that nagging doubt, I can’t shake the feeling this interpretation might hold merit.

The Book of Clarence brimmed with promise. It aimed to be a surrealist western reimagining of Jesus’s story, set against the backdrop of Jerusalem. Its ambition was clear: to spark conversations about knowledge and belief. And achieve those goals it did. However, reaching its ambitious destination required a series of jarring tonal shifts, squeezing more emotional impact from its lead than the script could comfortably support, and demanding constant investment in biblical narratives only loosely connected to the central story. Ultimately, The Book of Clarence emerges as a profoundly religious film, subverting both traditional conceptions of Jesus and my own expectations for its quality.

USA • ITALY | 2023 | 129 MINUTES | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

writer & director: Jeymes Samuel.

starring: LaKeith Stanfield, Omar Sy, RJ Cyler, David Oyelowo, Michael Ward, Alfre Woodard, Teyana Taylor, Caleb McLaughlin, Eric Kofi-Abrefa, Marianne Jean-Baptiste, James McAvoy & Benedict Cumberbatch.