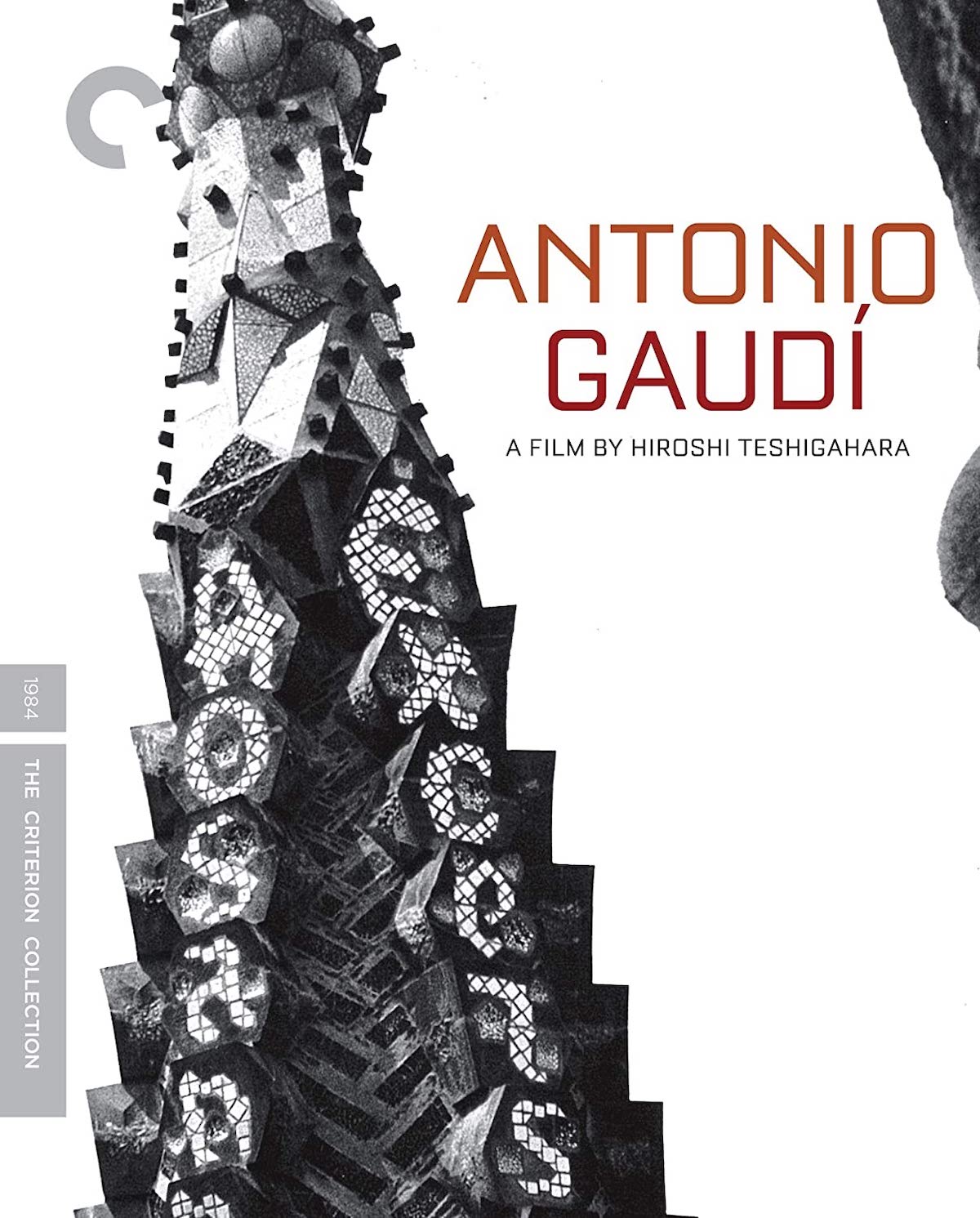

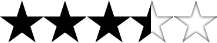

ANTONIO GAUDI (1984)

The work of Catalan architect Antonio Gaudí, as seen by Japanese New Wave director Hiroshi Teshigahara.

The work of Catalan architect Antonio Gaudí, as seen by Japanese New Wave director Hiroshi Teshigahara.

If you’re wondering “who’s Antonio Gaudí?” then this newly put-together package from Criterion should satisfy your curiosity on both an aesthetic and intellectual level. I would expect, though, that it’s most appealing to existing ‘fans’ of the distinctively Catalunyan architect, who became world-famous for a relatively small but beautiful body of work, including the hard-to-miss Basílica de la Sagrada Família—by far the biggest tourist draw for the city of Barcelona. Antoni (that’s the usual spelling of his name) Gaudí’s approach to colour and form is stunningly poetic and the techniques he devised were incredibly innovative. Way ahead of their fin de siècle era.

Antonio Gaudí‘s buildings sometimes seem to defy gravity and his understanding of load-bearing structure was born out of a lifelong fascination for nature. From childhood, he’d been obsessed with the observation of how plants and animals grow. He famously said that his teacher was “the tree,” and many of his buildings do appear to have grown out of the earth, their pillars like trunks from which roof rafters spread as boughs. Other columns flare and taper like human thigh bones. Many of his interiors resemble naturally eroded caverns and grottoes.

As his work evolved, the vertical became ever rarer and many of his contemporaries marvelled at how so slender, sloping columns could support such ambitious edifices. Many dismissed him as a madman and believed that his buildings would fall down. They didn’t understand the completely new techniques and radical approach that Gaudí introduced to design and engineering.

He maintained that for every problem we encounter, a solution already exists in nature. This profound belief was not coming from the kind of ‘green’ eco-awareness we may find today, but from his devout Catholicism which increased in intensity throughout his life. He strove to love every part of what he saw as God’s creation with equal fervour. Which is why his decorative facades and ironwork often elevate the lowlier, seldom championed creatures. Bats, lizards, and even ticks all contribute to the overall balance and beauty of creation and they can be found within his decorative vocabulary…

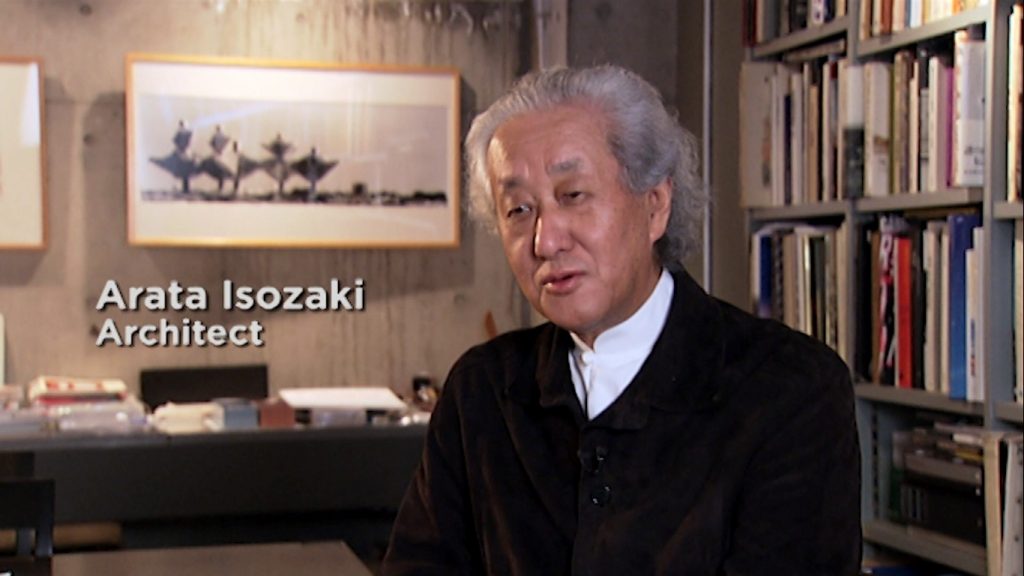

Japanese director Hiroshi Teshigahara came to international attention with his feature film Woman in the Dunes (1964) which won him the ‘Special Jury Prize’ at Cannes, and two Academy Award nominations for ‘Best Foreign Language Film’ and ‘Best Director’, no less. It was a fairly experimental hybrid of mystery thriller and relationship drama. The narrative was stitched together by visual symbolism, mainly involving the titular shifting sand…

This reliance on a kind of poetic cohesion had developed from his love of the visual arts and his professional involvement with Ikebana—the highly refined Japanese art of flower arranging. He was the son of the renowned sculptor and the Ikebana master known as Sofu. Teshigahara’s early films were short documentaries about artists, starting with the most famous of Japanese wood-block printmakers, Hokusai. His third documentary was about the Sogetsu School of Ikebana and the history of the aesthetic discipline.

With a typically Japanese approach, Teshigahara developed a kind of cross-genre fusion that exploited the obvious visual nature of film in meditating upon the visual elements of other art forms. Our experience of art and architecture is always subjective, and his use of the lens capitalises on this. We see something posing as objective reality, but of course, every frame is mediated by the filmmaking process.

In this documentary, Teshigahara takes us by the eyes and leads us through the wonderful world of Gaudí, showing us how he sees the subject. For the most part, there’s no comment or voice-over and he’s encouraging us to look now, think later. The viewer is coaxed into an aesthetic relationship with the material, letting go of the usual historical-contextual way of understanding and seeing things as, perhaps, Antoni Gaudí had.

The film opens with establishing shots of Barcelona, giving us a feel for the city before we get to Gaudí’s architecture. In hindsight, these scenes are not arbitrary through their relevance only gradually dawns on one toward the end of the film.

The first things we see are the streets of the Gothic quarter, its walls pockmarked with the scars left by bullets during the Spanish Civil War. We are shown the famous ‘dancing fountains’ delighting tourists with their multicoloured light show after dark. By day, the people stroll past works by other famous Catalunyan artists including Pablo Picasso and Juan Miro (both of whom were coming to prominence whilst Antoni Gaudí still lived), and Antoni Tapies (who would have only been three in 1926, when Gaudí died). Clearly, Barcelona is a city that has embraced public art, making it a top tourist destination. But Teshigahara also takes in the folk art, represented primarily here by traditional dancing on festival days…

If you can push past the folk dancing—rest assured, it’s a thankfully brief sequence—then the retinal rewards are well worth it alone. Teshigahara takes us through the amazing architecture from deep crypts that feel like ancient magical caves, to grand facades that seem to have grown out of the streets they now dominate, to intricate interiors where every detail, from floor to ceiling has passed through the imagination of the great Gaudí, often described as “God’s Architect”. It’s obvious early on that Teshigahara is a fan and this film is his visual love letter.

We are shown medieval icon paintings depicting the gruesome martyrdom of Barcelona’s favourite saints. This is the kind of imagery that young Gaudí grew up with and he was a devout believer throughout his life. He saw all his own work as an attempt to glorify God and His Creation.

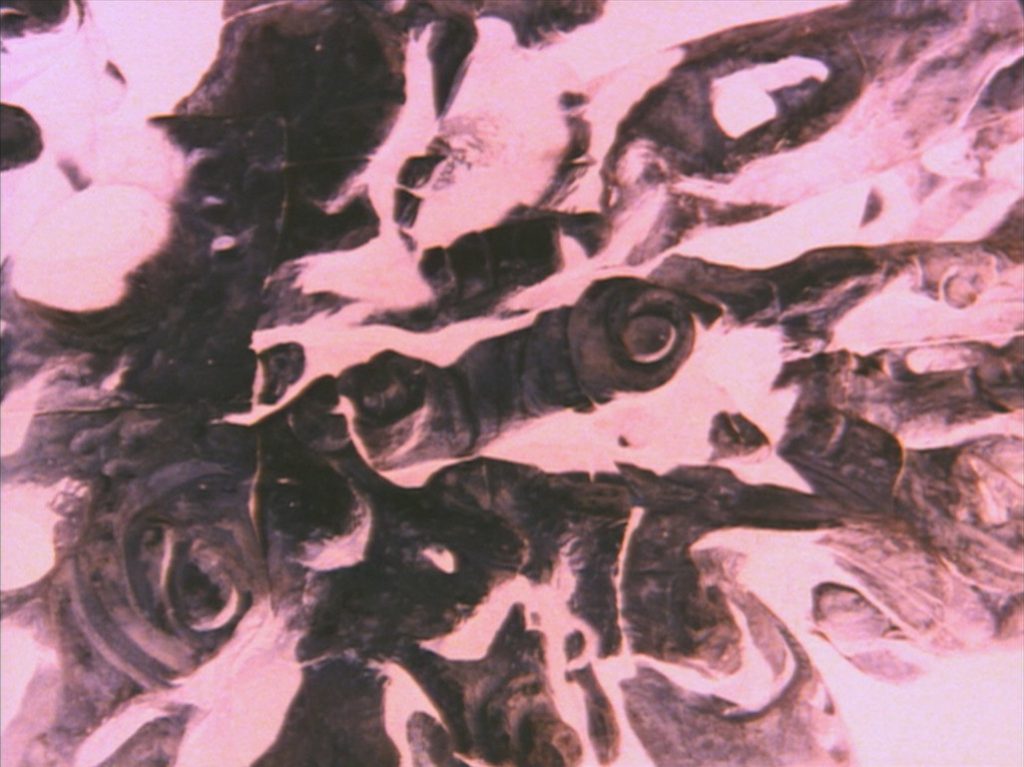

We see the rough stone walls and undulating terracotta roofs of the vernacular architecture and recognise the same earthy aspects in his great buildings, which employed local artisans and traditional craftsmen in their construction. The camera lingers on the unusual geological formations found in the hills surrounding Barcelona and we recognise their eroded shapes in Gaudí’s facades. Plants seem to grow out of rocks just as iron balcony railings and sinuous columns grow from walls and floors of Gaudí’s creations.

The buildings start to look like organic structures that might move, perhaps take a breath, and when Teshigahara takes us deep within their intimate interiors we see spinal vertebrae, the skulls of unborn foetuses, the spiral of an ammonite, the petrified undulation of the oak leaf…

Teshigahara uses the structure of filming and editing to explore all these many and varied connections that Gaudí celebrated in his buildings: Connections that bond humans and the natural world together as part of the vast glory of creation, physically and spiritually.

The otherworldly soundtrack by the avant-garde composer, Tôru Takemitsu (who also scored Woman in the Dunes) adds to the hypnotic effect whilst sometimes jarring the viewer or prodding with unexpected noises. The texture of the music echoes the tone and texture of the surfaces the camera roams over and draws attention to how we use the same terms to describe music as we do to discuss art and architecture—rhythm, tone, volume…

One may expect the 72-minute run-time to drag, but it doesn’t. Teshigahara’s ‘show-don’t-tell’ approach is refreshing and suits the subject matter perfectly, letting the spaces and forms speak for themselves. Gaudí’s architectural language is eloquent and intentionally narrative—the buildings tell their own stories. In fact, the very occasional snippets of dialogue are rather obtrusive and snap the viewer out of the dream-like state into which they may have drifted. I suppose their inclusion is to ensure the viewer doesn’t actually drift off.

director: Hiroshi Teshigahara.

starring: Isidro Puig Boada, Antoni Gaudí & Seiji Miyaguchi.