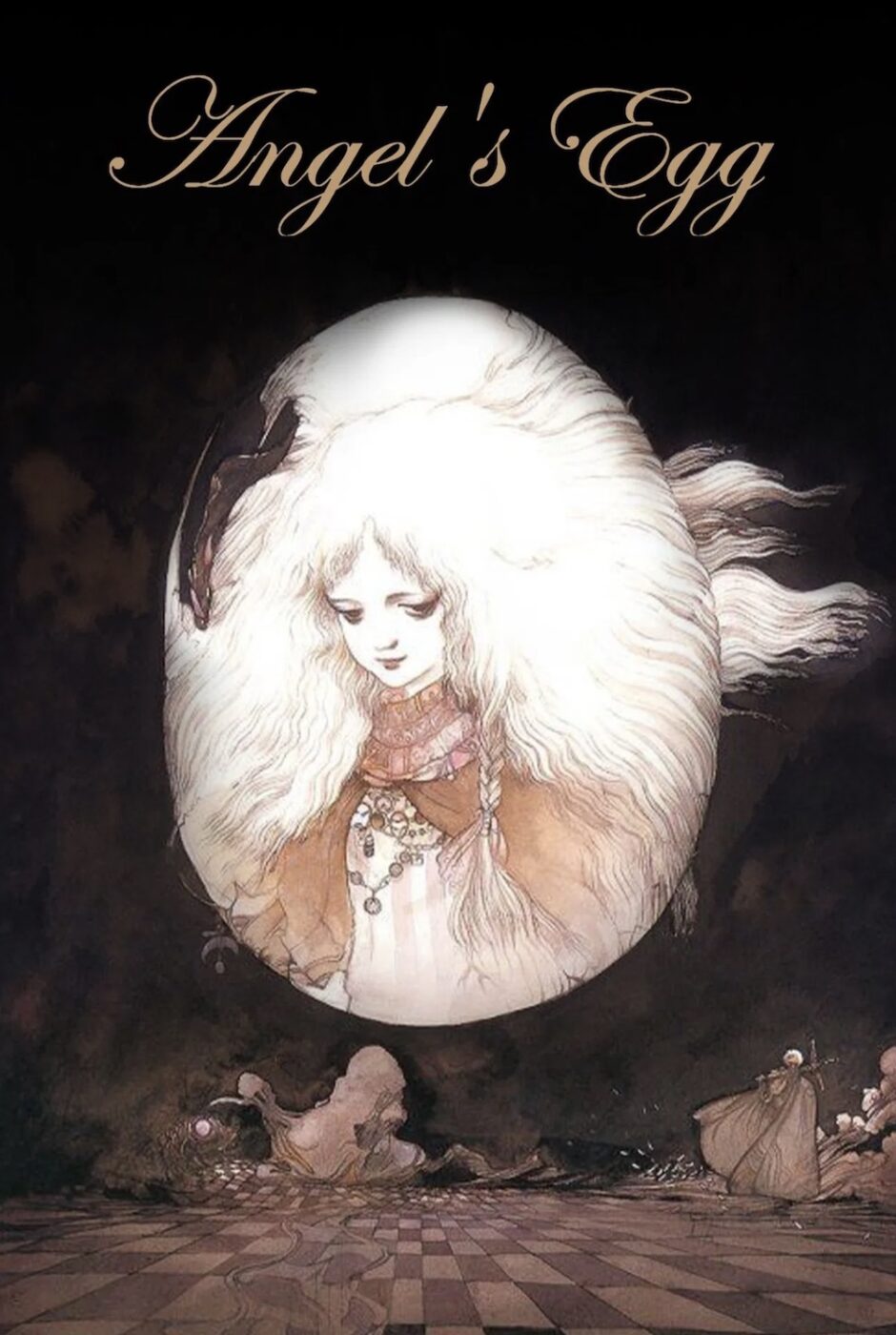

ANGEL’S EGG (1985)

In a desolate world, a young girl devoutly guards an egg of unknown origin, and encounters a boy carrying a cross who begins to question the nature of his faith and his mysterious mission.

In a desolate world, a young girl devoutly guards an egg of unknown origin, and encounters a boy carrying a cross who begins to question the nature of his faith and his mysterious mission.

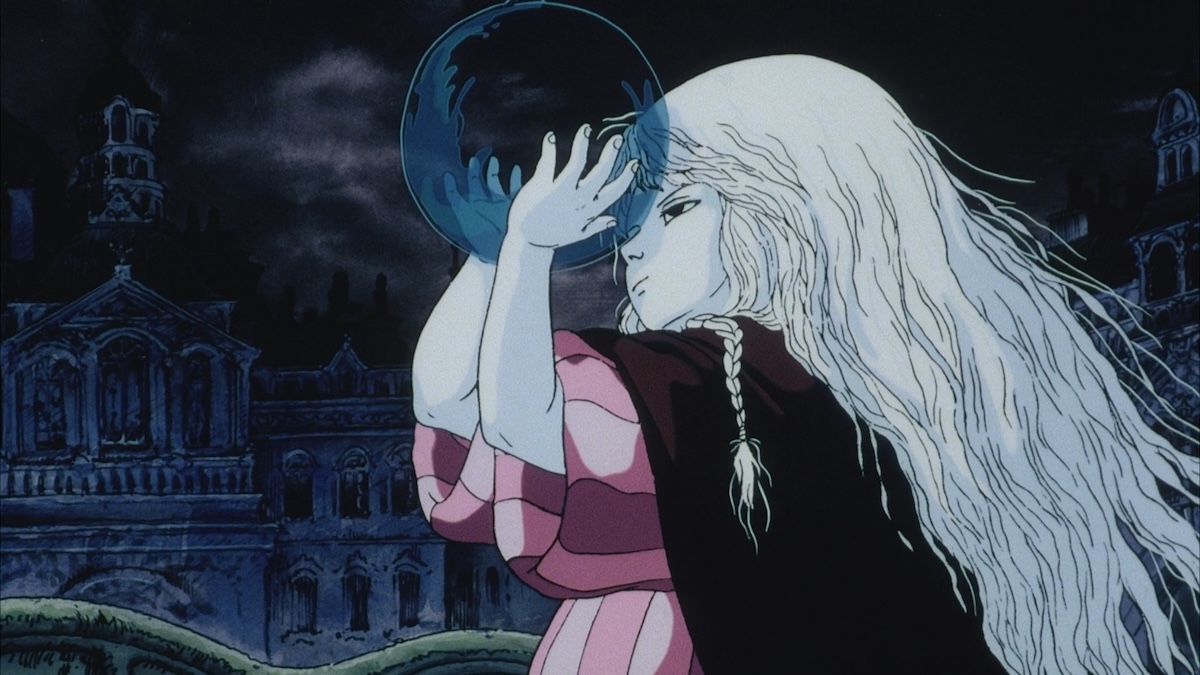

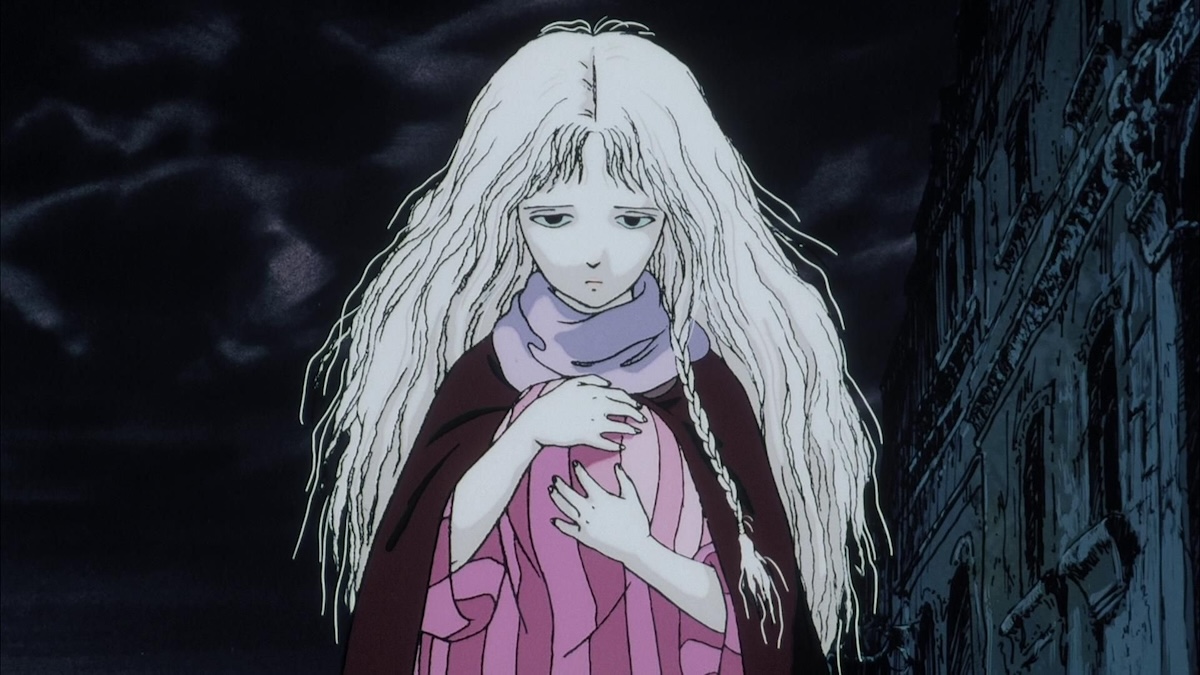

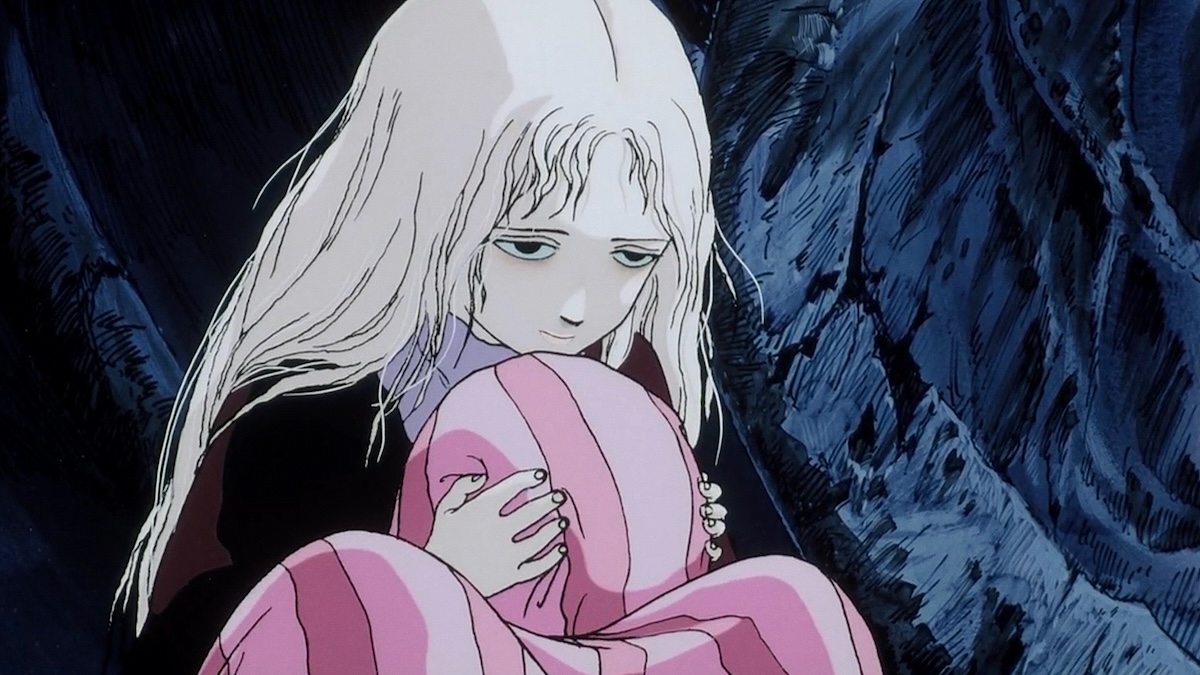

Visually, Mamoru Oshii and Yoshitaka Amano’s animated film Angel’s Egg / 天使のたまご is exquisite. Static gouache paintings occupy the background plane. At times, glimpses of the sky are shown during a sunset or the nocturne, while other times layering is used to define the plane into something recognisable, like the exterior of a building. The animations of the girl (Mako Hyōdō) and man (Jinpachi Nezu) use muted warms and cools to match the mood of their environment, making a cohesive visual experience. Neither of them, nor any of the fishermen shown in a hunt later on, are animated in a way that makes the viewer aware of them being a separate layer entirely—not like other older animated films I’ve seen.

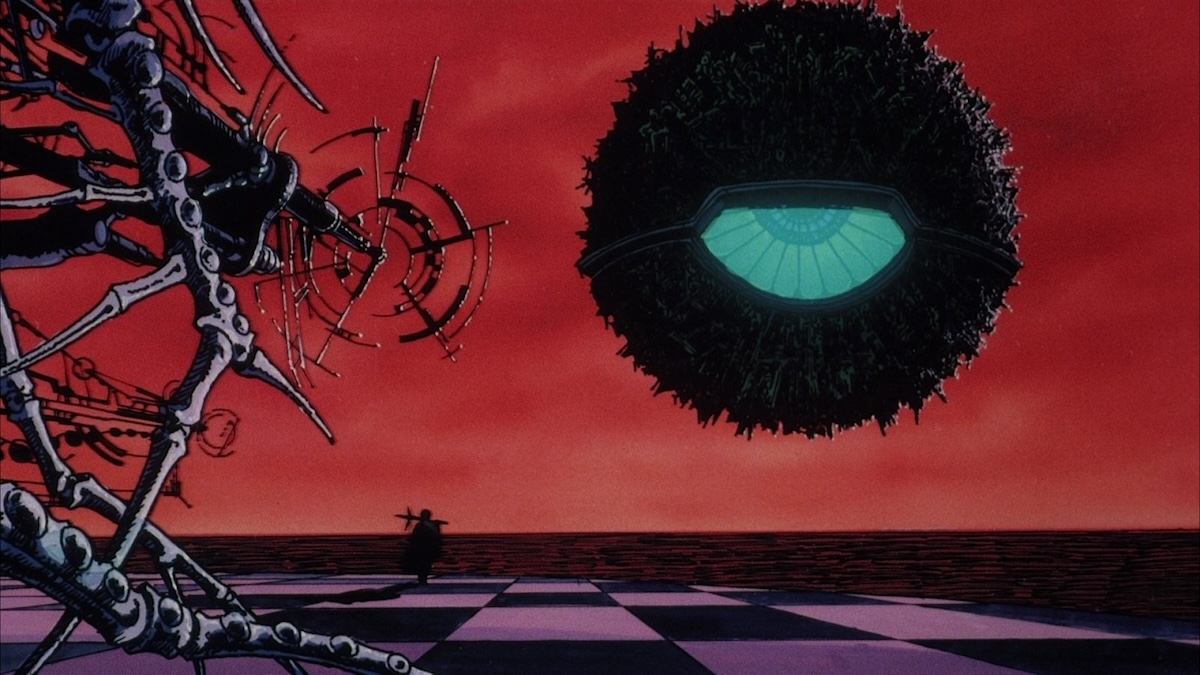

Amano’s presence is all over this film. The girl’s frayed, frenetic, thick hair; how facial features are drawn; the details in the attire of this world’s inhabitants; the textured architectural designs; and the use of industrialised technology—yet surprisingly, I see that these machines are bio-mechanical, which is of foreign design outside the Final Fantasy game series. Amano’s design for Angel’s Egg is darker than other work he has done. Life has always been infused into his art, yet in this film, the muted chroma stifles that vitality in favour of something more oppressive in tone. Angel’s Egg exists on its own, far removed from anything he’s ever done.

Amano’s use of stark black when creating shadows serves a purpose inherent to the shade itself: it draws the eye in and holds it captive. During my undergraduate degree, I learned that the use of black can either enhance or detract from a piece. On its own, black will rob the viewer’s attention away from everything else on the surface due to its potency. This can be sidestepped in two ways: by making everything within the composition just as robust as the black to pull one’s gaze out and move it about, or by mixing the black with a prominent colour in the painting to tone down its richness, allowing it to synthesise with the work as a whole.

Amano chooses to go with the former. With my eyes locked, the movement of the girl’s design recaptured my gaze, looking at the fine details that are her hair, her eyes, and her subtle emotional expressions, yet only to be cut off again by the penumbra. In conjunction with Yoshihiro Kanno’s score and Juro Sugimura’s cinematography, this man creates a waltz of visual and auditory cohesion that plays with the senses. This synthesis compels, unsettles, and overwhelms.

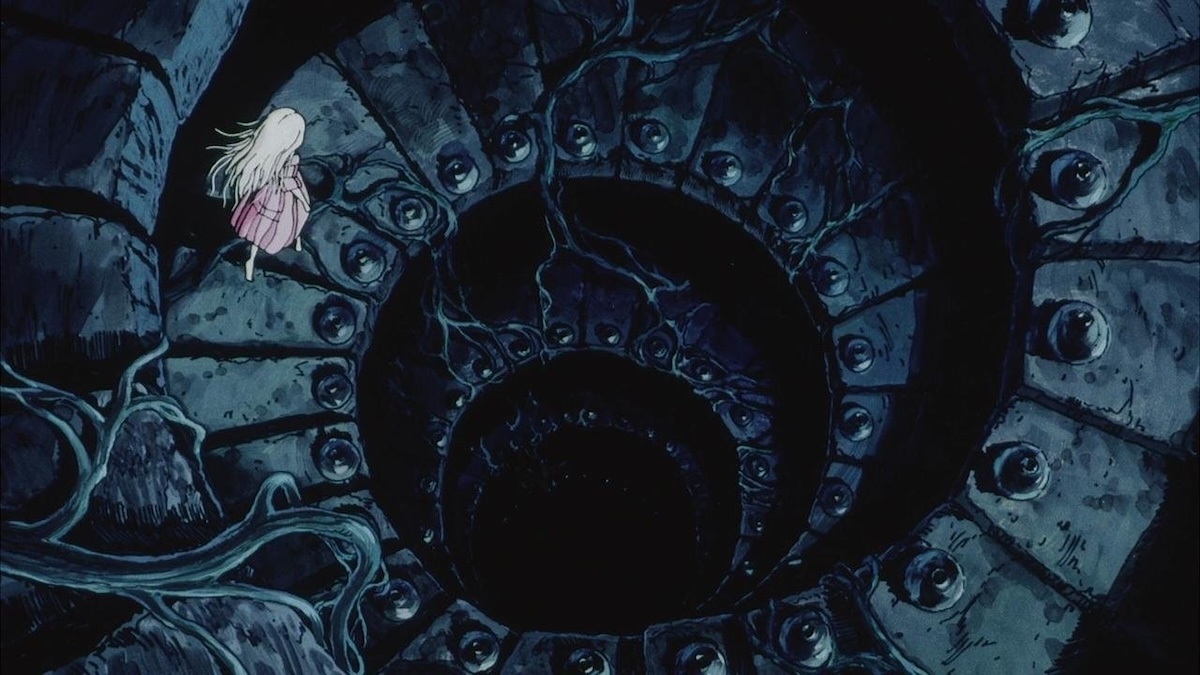

Buildings appear abandoned yet stand monolithic; shadows on structures bend and twist pragmatically yet remind me of earlier works within the German expressionist movement on account of how alive they look, but when they’re used to animate shades of a past long forgotten, the shadows flow with a soft and quiet intensity, like flowing water; figures traverse faintly yet swiftly between the cover of darkness inside an empty house of God or between alleyways. These moments are compositionally sound, yet the movement within is as fluid as Amano wants it to be, riding along the waves of animation’s limitlessness.

Sometimes the compositions are unable to contain such artistic expression that they burst at the seams, giving way to abstraction. When this occurs, these scenes evoke a sense of uncertainty and dread that aligns with how the girl feels, whether traversing the derelict streets of this unknown city for food or when the man endlessly pursues her, inquiring about the egg and musing about biblical catastrophe. These abstractions are alluring and yet lack the variety of colour that was typically found in other forms of visual divergence at the time. Most colour is absent here, and what remains are blues and purples and shades of black-and-white—a palette fitting of Angel’s Egg’s mood.

I caught elements of the film’s visuals that inspired many games I’ve played throughout my life. I saw dynamic camera angles, interior architecture, and fantastical iconography reminiscent of Fumito Ueda’s Ico and Shadow of the Colossus; I saw the constant deluge of rain, the dark fantasy setting, the white-haired girl, and the exterior design of its world’s architecture and couldn’t help but think of Keisuke Okabe’s Ender Lilies: Quietus of the Knights; I saw the highly detailed, macabre, and eldritch architecture and technology used in Team Cherry’s Hollow Knight; and I saw the ambient and emotional desolation, melancholy, desperation, and vigour found in Hidetaka Miyazaki’s Dark Souls and Bloodborne.

However, I also saw shades of things that have inspired Oshii. I saw bits of H.R Giger’s artistry in the manner that Ridley Scott used in his film Alien (1979). I also saw shades of Andrei Tarkovsky’s contemplative and slow-paced camerawork. Theodoros Angelopoulos’ focus on visual storytelling exists here, too, although this is solely based on my perception, as no evidence exists that states Oshii was a fan of the Greek auteur. It never ceases to amaze me to see how a collection of works from a single medium can inspire the work of other artists who reside in different mediums.

Oshii himself has stated Angel’s Egg was another attempt at exploring musings of existence that were present in his Lupin the Third film, which was unfortunately cancelled, and that the film’s interpretation is to each their own. However, these coalescing elements, including its theological imagery, have led many to conflate their interpretation with the creator’s intent. When this occurs, it tends to attract an innumerous amount of people towards said ‘intention,’ turning it into a consensus. I see this happen too often: how people define the value of art as the idea that gives it worth for them rather than the inherent value of the piece itself. Apparently, that isn’t enough. To them, art is a commodity, something that is meant to satiate their individual needs and ideas—nothing more.

The theological flavour of Angel’s Egg is merely that: a flavour. There are no hidden weighty biblical meanings nor purposefully concealed Jungian concepts—these readings exist separate from the film and need to be recognised as such. Oshii’s use of this flavour acts as points of guidance and parameter markers that create a confined space for the viewer to form ideas in. It also sets the tone and the foundation for the world the girl and the man are in, one where the doves sent out by Noah in search of dry land never return.

When I see the film, I feel as though it’s about faith, but specifically when one of faith is faced with cold indifference. The girl appears like a porcelain doll. She’s youthful, with fair skin—symbolising purity—yet her hair is frizzy, frail, and tangled, resembling that of an elderly woman. I especially feel this way whenever the camera is positioned behind her within the composition in combination with her attire. This contrast suggests the enduring nature of faith in this world.

The man walks in a beige-coloured military or enforcement uniform and a turquoise cape coat, carrying a bronze-coloured biotech club shaped like a crucifix—a sign of weaponising faith against those that still cling to their beliefs in the face of immense hardship. He’s the opposition to faith, lingering in the shade, slowly stalking the girl, like a predatory animal stalking its prey, and yet when the man confronts her, he’s instead inquisitive. He asks questions regarding the egg and its contents, her purpose in this world, how long she has kept hold of her tenacious ways in nurturing the egg, and so on. He even helps her stay dry during rainfall. It’s peculiar.

There’s something to be said about the girl’s and the man’s relationship. Faith, or philosophical suicide, as Albert Camus puts it in The Myth of Sisyphus, is an option one has when faced with the absurd. It’s an option many take instead of acceptance, as it sidesteps innate meaninglessness and plunges one into illusory transcendental values. They bury their heads within scriptures, vigorously rereading excerpts that do not make sense of their suffering but instead provide comfort, or maybe, in the case of the girl, a sense of fulfilment?

She gazes at the man with affection, whether he’s offering shelter from the rain or pursuing her with inquiries and intent. Her eyes close partially while a smile begins to surface, and at times, she’ll rest her head against his torso while walking underneath his cloak, like she becomes titillated by the presence of indifference itself. Their dynamic is odd but intriguing, as, when their dialogue is combined with all of the theological imagery, their relationship mirrors ones found in a Tarkovsky film.

That being said, I think all of this wealth within Angel’s Egg is hampered by some infantile editing choices and how unnatural some of its dialogue comes off. Oshii wanted Angel’s Egg to be a contemplative and slow-paced film, like the work of Tarkovsky, and yet he didn’t study his work enough. What Oshii missed when studying Tarkovsky’s work is that there are elements within his films that form an invisible connection between the world at display and the audience, which makes the use of slow-moving, almost roving, and static shots feel naturalistic.

Tarkovsky’s films have a lot more movement in them, albeit still slow, while his static shots are presented as though we’re frozen in a moment of time, peering into something personal, and yet both approaches don’t make the viewer aware of the time spent on the shot. I believe this is because of how Tarkovsky crafts his worlds with relatability and familiarity. His characters go through the same plights as us: the struggle with faith and the philosophical, of sin and transgression, of lucidity and insanity. This craft is then reflected in the environments, as they feel oppressive, worn down, and stifling but sometimes overwhelmingly open still. They can be felt, as though they are a character within the film.

This isn’t the case for Angel’s Egg. Time that could have been used to further cement these feelings of relatability and familiarity within its environments, quality of dialogue, and emotional conveyance was instead predicated towards visual abstraction. A static shot of the man sitting at an open flame while the girl rests sound asleep doesn’t transfix me nearly as much as it could have had these anguishes existed prior, which would have prevented me from becoming aware of the camera’s existence. Instead, moments like this scene come off as dead air, a waiting period, or even a loading screen.

Some of these shots were even painful to sit through. At one point in the film, something profound is revealed via a slow pulling back of the camera, cutting every so often to reveal more and more, yet some of these cuts mirror the shot prior but at a different tilt. They account for a lot of time within this particular sequence of shots that they feel like excess, like fat. It’s nauseating and evocative of freshman energy.

Then there are moments where the man spews out theological banter only for his dialogue to end and the camera to stay locked onto his face for nearly six seconds before cutting, yet moments that should be longer and that should show off the potential of animation are cut way too soon, like water violently flowing through a canal from a biblical deluge to sell the severity of what has just occurred before. It’s perplexing to think someone can approach a work of art a certain way without fully understanding it. Then again, this happens all the contemporary cinematic climate, doesn’t it?

Then there are the man’s exchanges with the girl. While in the midst of some small talk, the man unleashes these tirades about the nature of faith. He doesn’t do them often, but when he does, it becomes more evocative of the back-and-forth found in Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972) than Stalker (1979) when viewing them closely—they appear one-sided. There’s no contention to be heard from the girl to enamour the man’s ideological position. He is indeed enamoured by her tenacity in filling the bottle with liquid and the devotion she has toward nurturing the egg, but that ideological wealth is missing from her end.

It doesn’t help that some of the man’s dialogue feels a bit clunky, and that’s thanks to the new translation used for the 4K being worse than the fan translation that has been around for years. It’s most noticeable in the scene of the man recalling The Story of Noah. This isn’t the first time I’ve read of an anime film or show getting a new translation when something better already exists.

The collection of these shortcomings prevented me from being fully enamoured by this film’s presence. I felt more of a push-and-pull effect going on. I was locked in for the most part, but even a moment’s push can make being pulled back in all the more difficult. Slow-moving, meditative works of cinema, like Angel’s Egg, are as fragile as any other genre. If a filmmaker doesn’t know the methodology towards their approach, then they run the risk of their creation feeling stilted and janky.

Angel’s Egg is good, not great. Yet, despite this, I have a lot of respect for it as a film. It was Oshii’s first original project, which he chose to make into a collaborative experience with Amano, that made way for the foundation of his later works. Angel’s Egg had to hatch and learn to crawl for Ghost in the Shell (1995) and Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004) to be able to run at a full sprint.

Without it, Oshii wouldn’t be where he is, even though the film prevented him from being employed by studios for the next three years. Without it, many of the games influenced by it wouldn’t exist today. Can you imagine a world without Ico, without Bloodborne, without Hollow Knight? Sounds awful, right? I may not have been enamoured by it like Ghost in the Shell and Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, but I’m still picking up a physical copy whenever it’s released. With its recent success at the box office, it’s an inevitability. Heck, maybe in time I’ll take more of a liking to it, as respect gives way to adoration. Maybe.

JAPAN | 1985 | 71 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

writer & director: Mamoru Oshii.

voices: Jinpachi Nezu & Mako Hyōdō (Japanese) • Justice Slocum & Brianna Knickerbocker (English).