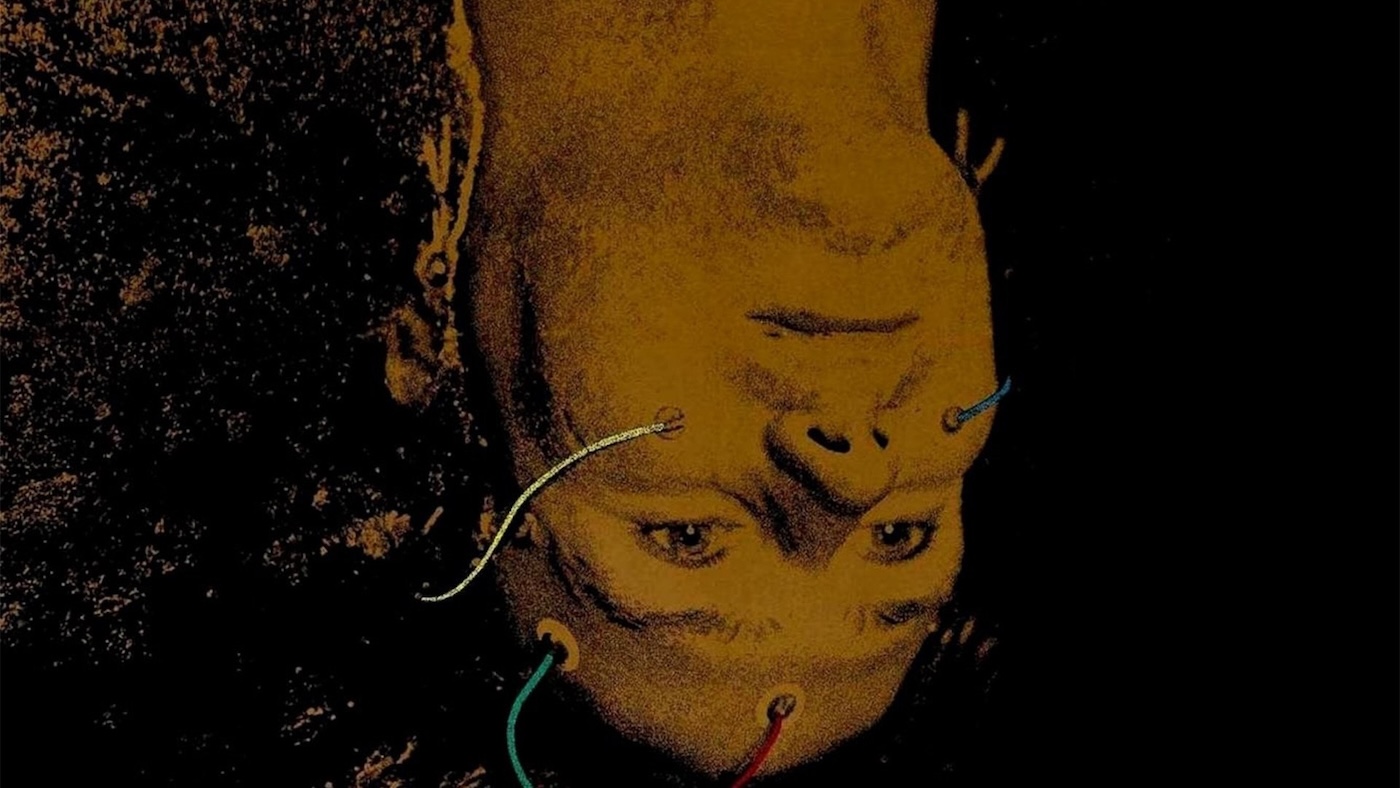

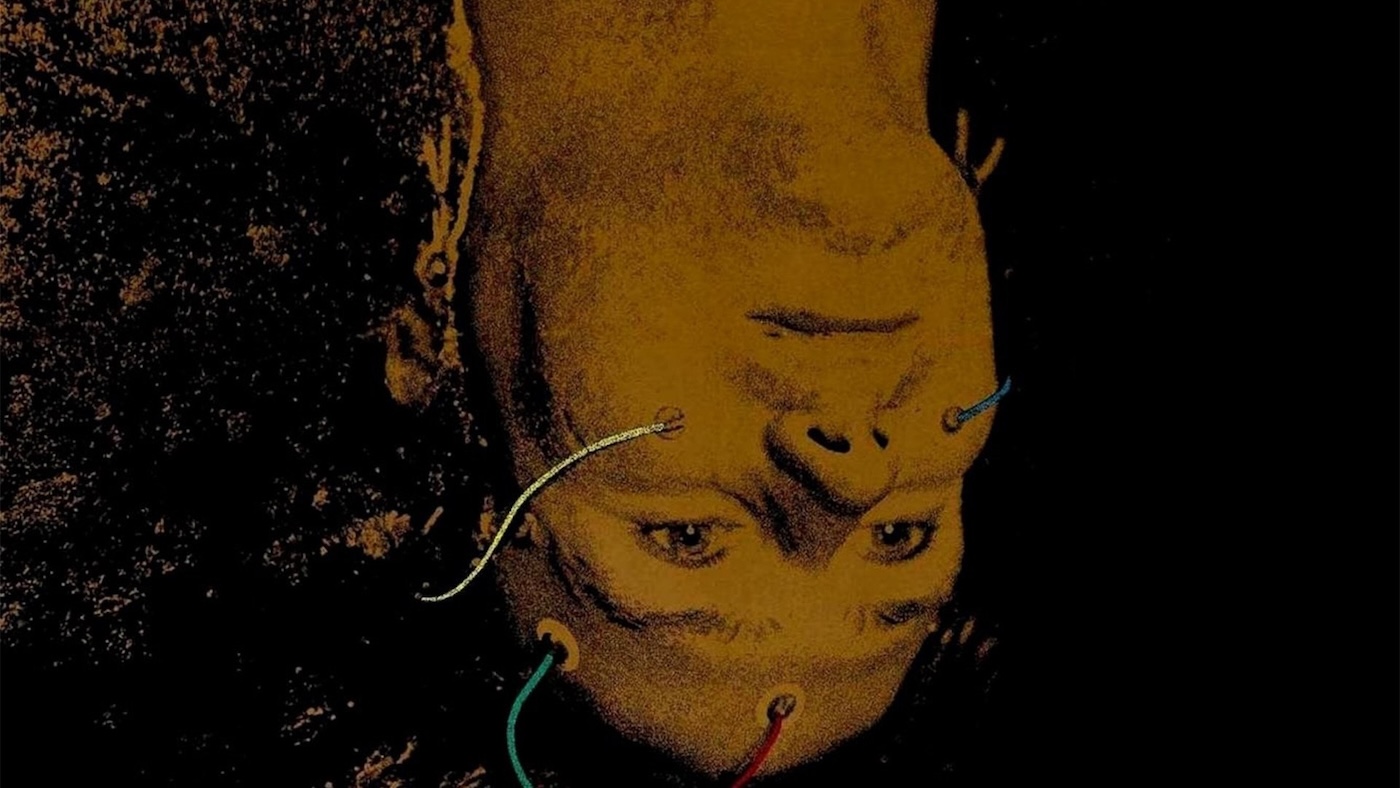

ALTERED STATES (1980)

A psycho-physiologist experiments with drugs and a sensory-deprivation tank and has visions he believes are genetic memories.

A psycho-physiologist experiments with drugs and a sensory-deprivation tank and has visions he believes are genetic memories.

British director Ken Russell was a bold and adventurous filmmaker. His creative output that spanned over four decades could never be summed up as boring or mainstream. Despite many of his films being commercial failures, Russell never stopped working. His last short film, A Kitten for Hitler (2007), was released only four years before his death.

Russell’s most successful period spanned 15 years, starting with Women in Love (1969) and ending with Crimes of Passion (1984). Throughout this time, the director made an impressive 11 feature films. Several drew on the director’s love of music, including The Music Lovers (1971), which concerned 19th-century Russian composer Tchaikovsky, and the fantasy musical Tommy (1975), based on The Who‘s 1969 rock opera album. The latter proved to be Russell’s biggest commercial hit, earning over $34M against a $3M budget.

Out of this creatively prodigious timeframe, Russell directed two very different but equally brilliant films. The first was The Devils (1971), starring Oliver Reed and Vanessa Redgrave, and based in part on Aldous Huxley’s non-fiction book The Devils of Loudun. This historical psychological drama tells the story of 17th-century Roman Catholic Priest Urbain Grandier, who was accused of witchcraft after a group of nuns said they had been possessed by demons.

Grandier was singled out as being solely responsible and subsequently suffered hideous torture, after which he was burnt at the stake. Even though it enjoyed much financial success—especially in the UK—it was hugely controversial for its sexual and violent content, and as a result, was heavily censored by its distributor Warner Bros. In the years since its release, there have been several different versions, all of varying length depending on which country you are seeing it in, but I urge anyone to check it out as it’s an incredibly powerful and original piece of cinema. This leads us to Altered States, which, I think anyway, has to be considered the second most notable film from this era.

Altered States, to put it mildly, is like nothing you have ever seen before. To think that it was a Hollywood-produced film simply beggars belief, if nothing else because it contains scenes involving experimentation with psychedelic drugs—and that’s just for starters. This was Ken Russell’s one and only time working in the realm of science fiction, but oh boy, he doesn’t do things by halves! This absolutely crazy movie plays out like some modern-day Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde fever dream; with its common theme of duality and transformation, along with such heady topics like science versus religion, the evolution of consciousness, and even the complex relationship between love and selfishness. Boring, it is not!

As the film opens, we see doctor Edward Jessup (William Hurt) immersed in a sensory deprivation tank. At this early stage, his work involves studying schizophrenia and he’s exploring different states of human consciousness. Years later, Jessup goes to Mexico and takes part in a tribal ceremony where he drinks an hallucinogenic brew. Following his intense psychedelic episode, the doctor takes a sample of the concoction back home where he uses it with his new scientific obsession: that the human mind retains ancestral memories encoded in its DNA. Jessup seeks to unlock these primal experiences by combining isolation with the tribe’s hallucinogens. His experiments become increasingly reckless as he consumes higher doses of the brew, eventually regressing into a simian form; literally changing into his primitive self. To say any more at this point would ruin the film, but suffice to say, the ending is quite the spectacle.

On paper, everything about it sounds ridiculous and even silly, but for the most part it holds together well. This, I think, is thanks to the collaborative pairing of both Russell and US playwright, novelist, and screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky. However, the word collaborative can only be used loosely, as the two of them apparently locked horns repeatedly during the production, with Chayefsky eventually removing his name from the credits, using the pseudonym (taken from his full name) of ‘Sidney Aaron’.

The main reason behind their fraught working relationship was down to Chayefsky wanting strict creative control over his script. There was no room for any tweaking to his written words, and so he immediately clashed with Russell after the director started to try and improvise with the text. Chayefsky even demanded that certain words had to be spoken in a particular way. Nevertheless, this combination of intellectual ideas coupled with Russell’s trademark operatic visual excess makes for one happy accident of a film. What could have been an outright disaster somehow ended up to be quite the opposite.

Chayefsky started off his writing career in television. His earliest teleplays in the 1950s often focussed on the quiet struggles of everyday Americans and have now been recognised as helping define what became known as television’s “golden age”. Building on his TV success, Chayefsky transitioned seamlessly into theatre, fiction, and film. His work retained a sharp social conscience and deep understanding for ordinary people navigating the trials and tribulations of modern life. Over the course of his career, he earned three Academy Awards for ‘Best Screenplay’; Marty (1955); The Hospital (1971) and Network (1976)—something which, even to this day, is rarely repeated.

His Altered States novel was partly inspired by the real-life research of Dr John C. Lilly, a neuroscientist and psychoanalyst who, during the 1950s and 1960s, conducted pioneering experiments in his invented sensory deprivation tanks. Lilly’s studies investigated the boundaries of consciousness by immersing subjects—and often himself—in complete darkness and silence while under the influence of psychoactive substances such as LSD, mescaline, and ketamine. He claimed to experience altered perceptions of time, self, and even communication with other intelligences. These fascinating studies that seemed to fuse science and spirituality immediately sparked something within Chayefsky, and so his story of a Harvard scientist obsessed with uncovering the original state of human consciousness was born.

Right from the off, Russell’s opening scene ticks all the boxes on how you should begin a film: this is achieved because the imagery and soundtrack hold your attention and demand questions. At first, we hear the strange sounds of Hurt’s Dr Jessup inside the isolation tank; subsonic hums, a distant heartbeat, breathing underwater, from which we then see a close-up of his face wearing goggles and some sort of diving helmet apparatus to help him breathe. The camera lingers long over this odd-looking visage, while beautiful yet ever so slightly sinister music plays in the background. As film openings go, this is way above average. It has echoes of the beginning for Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979), with its unusual score and film title slowly forming.

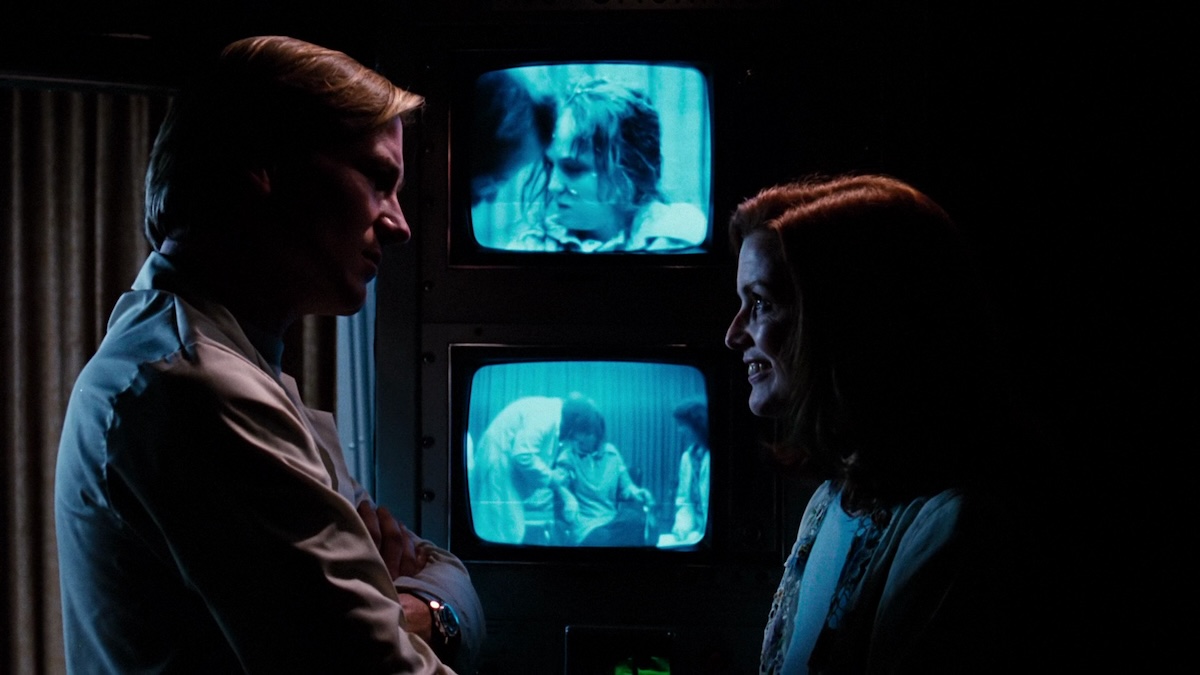

If you have seen any of Russell’s past work, then you will know he has never been a slouch when it comes to bringing a strong visual texture to the screen, and here is no exception. Cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth (Blade Runner) gives the film a rich visual palette of contrasts: sterile laboratory blues and whites that dissolve into crimson and gold hallucinations. Backing up the lush cinematography are the trippy and eye-popping visual effects, largely created by technical genius Bran Ferren. Ferren’s earlier work before moving into film involved pioneering lighting and video effects at huge stadium concerts for the likes of Pink Floyd, David Bowie, and R.E.M.

It’s fair to say, that viewed today, these effects do look a little dated, but they never come across as cheap or ineffective. These were largely practical: employing various optical experiments using a combination of light and mirrors. The end result remains startling and hypnotic at times—not bad when you consider these were all achieved long before CGI existed. Along with the dazzling cinematography and superb special effects, American composer John Corigliano (Revolution), in his first feature film score, crafted a powerful orchestral work that saw an Academy Award nomination. The music veers from haunting percussion sounds, to sweeping strings, creating a hypnotic and visceral soundscape.

Regarding the performances, they’re all strong, but William Hurt’s acting in the lead role has to be considered the stand-out here, and what makes it all the more impressive is that this was Hurt’s screen début. He brings a quiet intensity to his character of Dr Edward Jessup. Even during scenes filled with Russell’s visual chaos, Hurt’s stillness in moments of contemplation (the narrowing of his eyes, the clipped rhythm of his voice)) shows us that the turmoil he’s experiencing is coming from within. Before this, Hurt was a highly-regarded New York theatre actor. He learned his craft at the prestigious Juilliard School, after graduating he joined the Circle Repertory Company, one of the most respected off-Broadway troupes of the 1970s.

Witnessing Hurt on screen, his classical training comes through: the precise way he moves, how he talks, this all helps add a certain quality to his performance. Unlike previous ‘man-made monster’ type of films (1931’s Frankenstein), Hurt performs Jessup not as a conventional movie scientist but as a kind of tragic philosopher. Unfortunately, like so many other cautionary scientific tales, his obsession takes him down a very dark path, one that nearly ends his life entirely.

Opposite Hurt, Blair Brown (Fringe) brings warmth and quiet strength to Emily Jessup, the anthropologist who, despite their troubled marriage, still loves him throughout. Brown, a seasoned stage actress herself, matches Hurt’s intensity without ever being overshadowed. Her Emily isn’t the stereotypical anxious spouse; she’s smart, calm, and compassionate. The supporting cast are also excellent: Bob Balaban (Close Encounters of the Third Kind) plays Jessup’s sceptical colleague Arthur with a type of nervy humour, while Charles Haid’s (Hill Street Blues) Mason adds some levity to the film as the no-nonsense lab partner. Together, they all inject a real human element to the story and help stop it becoming all about the science. In the hands of some other filmmaker, this could have ended up being a cold, emotionless film. Instead, what you are left with is a tale that has a degree of empathy running through its DNA; the characters feel real and care about each other.

I’d be lying if I said Altered States is a flat-out masterpiece; there are some problematic elements that stick out, resulting in some interesting issues along the way. To begin with, the creative clashing of styles between Russell and Chayefsky soon becomes quite obvious. Russell’s visual flamboyance—sometimes excessive—can sit badly against Chayefsky’s philosophical dialogue, with a few scenes drifting dangerously into the over-the-top and/or camp territory. And then there’s the pacing…

The film can never be accused of dragging, but it’s evident the screenplay’s truncated large parts of the book. During the first act, Hurt and Brown first meet at a party, then you see them shortly afterwards talking and then they go back to her apartment and have sex, and before you know it, they’re getting married. And then shortly after that, they’ve clearly separated (with at least five years having gone by), with a few children now in tow. It’s a little jarring to say the least, and I wonder if anything around this timeframe had been edited out and left on the cutting room floor. It doesn’t ruin the overall flow of the film, but it’s certainly noticeable.

Another issue worth mentioning is that the film feels like it ends a bit too suddenly. This sticks out more as what occurs just before the conclusion is so spectacular and dramatic, that when the end comes you really notice it. In my humble opinion, there could have been at least one more scene of just a few minutes to give you time to decompress and fully get your head around everything. Again, did something get cut, or did they simply run out of money? We will never know, but it felt a little ‘off’ to me. This is a minor quibble, though, in what’s overall a fascinating, entertaining, and thought-provoking sci-fi horror thriller.

USA | 1980 | 103 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

This Criterion Collection 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray disc is a treat for your optic and aural senses. The eye-popping visuals throughout Ken Russell’s metaphysical sci-fi film simply look incredible; the overall picture quality is sharp, with colours looking vibrant and fresh. The scenes filmed against a low-light setting, such as the one when Hurt’s primitive self breaks into the city zoo, are full of clarity with perfectly balanced dark contrasts that probably haven’t looked this good since its theatrical release. Equally impressive is the new DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 surround sound, providing a crisp yet powerful range for your ears to feast on, with nary a hint of distortion in sight.

The extras are also top-notch: stand-outs are, first, two archival interviews. One is with director Ken Russell, and the second with a young-looking William Hurt; both of these are chock-full of facts that film fans will find highly interesting. The second is a new interview recorded for this disc, and is with VFX wizard Bran Ferren that gives great insight into how he achieved some of the then ground-breaking effects. All in all, this is another superb Criterion release that will surely please fans of Russell’s marvellously crazy sci-fi movie.

director: Ken Russell.

writer: Sidney Aaron (based on the novel written by Paddy Chayefsky).

starring: William Hurt, Blair Brown, Bob Balaban, Charles Haid, Thaao Penghlis, Dori Brenner & Drew Barrymore.