ALICE IN THE CITIES (1974)

A German journalist is saddled with a nine-year-old girl after encountering her mother at a New York airport.

A German journalist is saddled with a nine-year-old girl after encountering her mother at a New York airport.

A man sleeps in a motel room, a modern inn for the road-weary traveller. It’s a motel much like any other, and he believes they’ve all begun to blur together. A television blares in the background, shattering the emptiness that surrounds him. And when he dreams, he dreams of the road again, of the life of movement he must wake up to, and of the endless journey he must embark upon once more.

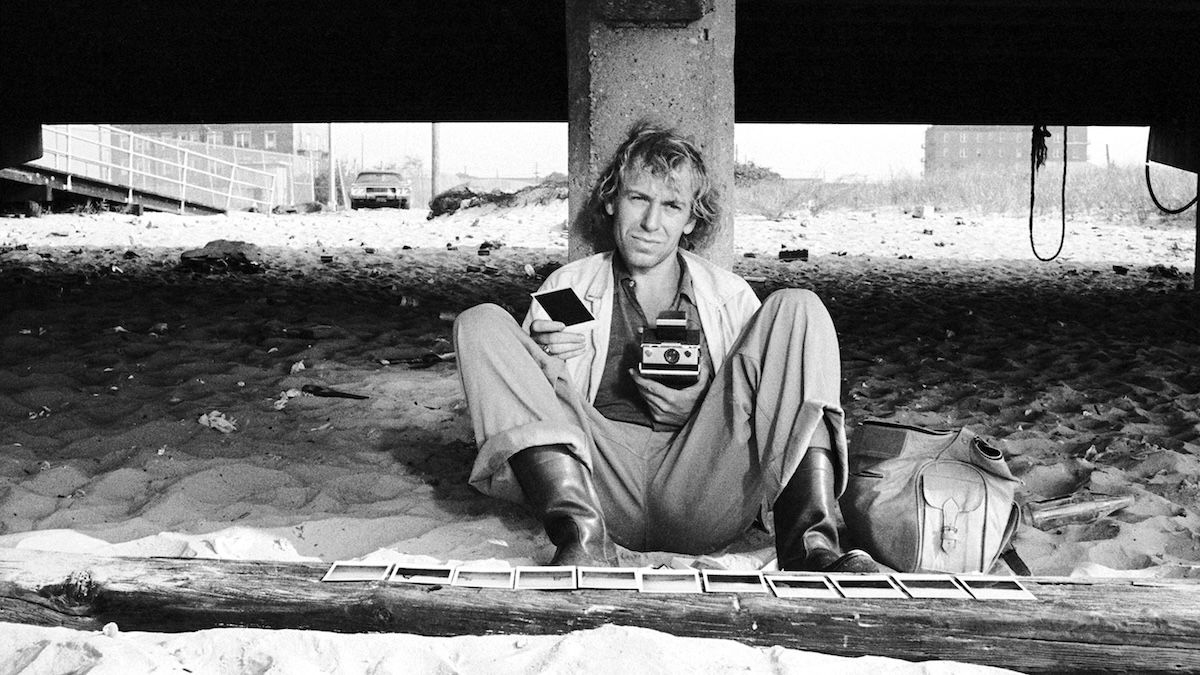

Philip (Rüdiger Vogler) is a writer on the road. A deadline looms large, but he has yet to write a single word. A debilitating bout of writer’s block has left him with nothing to say in his article about the United States. Instead, he has been taking photographs of the American landscape, of shapes that, in his mind’s eye, are gradually coalescing into a single image of a national identity. His editor (Ernest Boehm) is less than impressed; he cuts a scathing figure, reprimanding Philip before firing him.

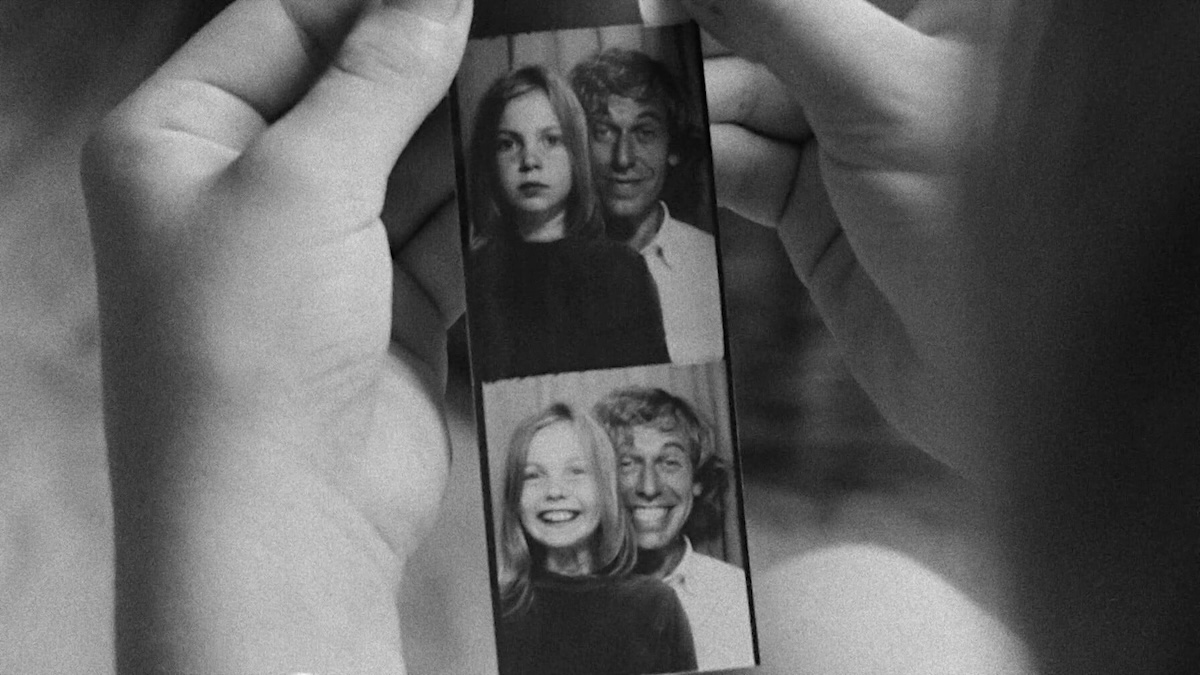

Philip believes he’ll find inspiration for his article after returning to his native Germany. At the airport, he meets Lisa van Dam (Lisa Kreuzer) and her nine-year-old daughter, Alice (Yella Rottländer). But since air traffic controllers are on strike, they can only get a flight to Amsterdam in the morning, so the three of them band together for the night. However, in a panic, Lisa leaves Alice in Philip’s care, asking him to take her to Amsterdam for her, which he does. But when Lisa doesn’t arrive, Philip finds himself in a difficult situation…

Alice in the Cities / Alice in den Städten, writer and director Wim Wenders’ fourth feature, is a definitive work in his estimable career. The first entry into what would become known as The Road Movie Trilogy (1974-76), Alice in the Cities finds the New German Cinema director carving out a new niche: a cinema of loneliness, populated by aimless, listless characters who are in search for something meaningful. As his first personal film, Wenders creates a work that is not only stylistically unique to himself, but also a beautiful meditation on what it means to grow up in a world that’s disinterested with our existence, making it a transfixing viewing regardless of your age.

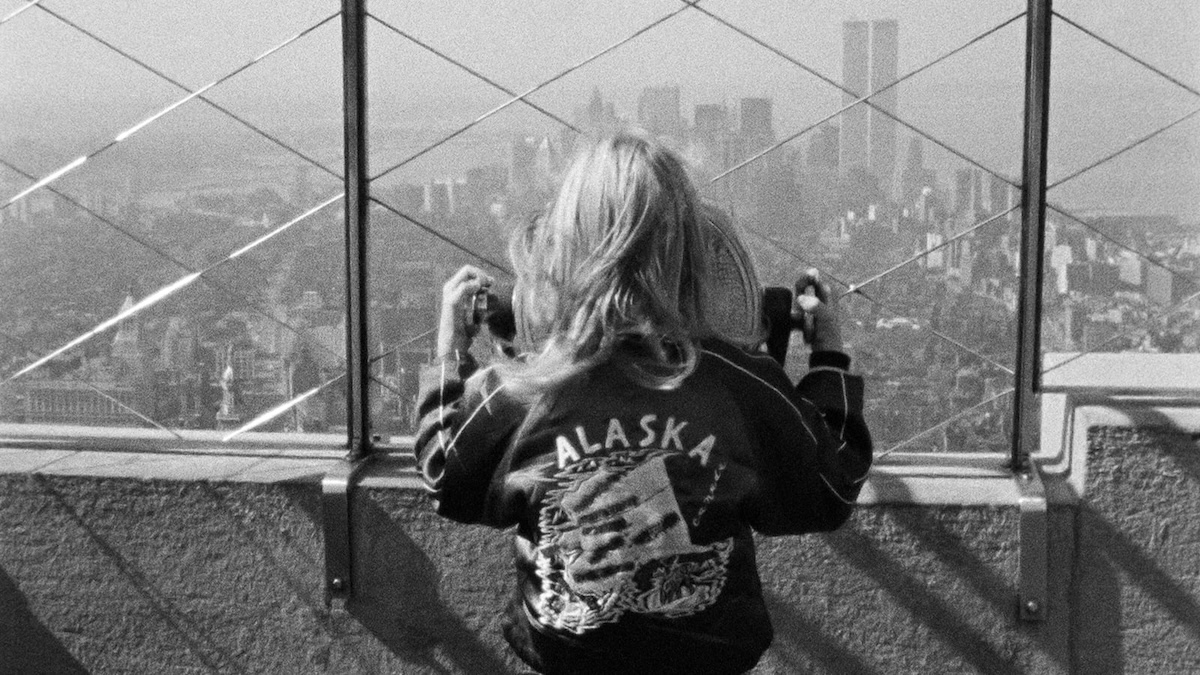

Alice in the Cities is, of course, a road movie—hence the name of the trilogy. But it also finds itself as a flag-bearer for another genre: the city symphony. This film genre originated in the 1920s and provided city dwellers the opportunity to revel in the vibrant, electric space that was their home. The size and scope of the metropolis was displayed in all its frightening and awe-inspiring glory. Originally, these films would have no central plot or identifiable protagonists—the city itself was the main character, one with which everyone could readily identify.

Some city symphonies are joyful, lyrical works, while others are less optimistic about the role urban environments play in our lives. Alice in the Cities appears to be an intriguing combination of both, though it initially seems to argue the latter. Wim Wenders wasn’t the first director to explore this ambivalent relationship between city life and its effect on impressionable young people. Truffaut occasionally teases us with an avant-garde, genre-bending work in The 400 Blows (1959). However, while this film is primarily a coming-of-age drama, it does hint at the potential degradation of youth in urban settings.

Shots of Paris slowly waking up, of the young Antoine wandering the night-time streets, and bright lights from towering buildings. It never becomes a full-blown city symphony, but it is a perfect example of how filmmakers connect character and city, weaving them together to form a cohesive narrative. Much like Wenders did a decade and a half later, Truffaut positions his protagonist in a cavernous cityscape to highlight the sheer extent of their loneliness.

Some other well-known examples include Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967)—Paris again, albeit a much more pronounced city symphony than Truffaut’s. Woody Allen’s Manhattan (1979) is another example of embedding a personal story within a city symphony. Intriguingly, the first film in this genre was also shot in Manhattan: the aptly named Manhatta (1921). As an ardent film fanatic, it’s a clue that Allen was both paying homage to the annals of history from which filmmakers so often draw, while simultaneously adulating his home metropolis.

If you want a more modern example of the city symphony, you can watch the excellent From Scotland with Love (2014), directed by Virginia Heath and accompanied by a gorgeous soundtrack by King Creosote. Factories, streets, and pubs are all shown to be the lifeblood of such compacted societies, places where people are brought together both through work and leisure. It’s an exemplar of a celebratory ode to cities rich in history, creating a tapestry of an entire nation in the process.

So, where does Alice in the Cities fall into this genre? Somewhere in the middle. We location-hop for the majority of the narrative, fulfilling the road-movie component of the story. Though a true city symphony arguably should focus on a single metropolis, Alice in the Cities, much like the title suggests, is keen to explore a variety of different urban environments. As a result, Wenders’ fourth feature isn’t as dedicated a city film as some of his later works—such as the sublime Wings of Desire (1987), which features a meditative tone as pensive angels hover over Berlin—yet it still demonstrates the same concern regarding urban spaces.

From the outset of the story, there is a preoccupation with the effect such large, dwarfing constructs have on us as a species and individuals. Does it have a malignant impact on the human condition, or a binding, unifying one? At times, Wenders appears pessimistic. Sheep graze in front of factories billowing smoke, providing a striking visual contrast between natural and urban settings. There is an aspect of spiritual decay attached to such industrial environments.

Indeed, there’s something vaguely unsettling about some of the cities our adventuring duo visit. As Philip and Alice meander around Ruhr, trying to find her grandmother’s house, they drive past street after street of condemned houses. Each building is beautiful, yet each is destined for destruction. “They don’t bring enough rent,” Philip informs the young Alice, who’s confused by the decision to wreck pretty things. “House graves,” she whispers, fascinated.

In much the same way as Truffaut, Wenders diminishes the importance of his protagonists by placing them amongst such colossal structures. By doing this, existential questions are subtly introduced into the narrative. The city becomes emblematic of the protagonist’s fears of cosmic isolation, and a disquieting nihilism pervades their psyche.

However, they are unaware of this. Philip especially seems conflicted, finding the city to be a comforting environment, yet also one he cannot leave without becoming desperately lonely. When the story starts, Philip has only just left New York and finds himself on the dusty roads out into the Midwest. “Once you leave New York, nothing changes anymore. It all looks the same. You can’t imagine anything anymore. Above all, you can’t imagine any change. I became estranged from myself. All I could imagine was going on and on like this forever.”

This is the first time we can be certain Philip is speaking openly. Talking with his ex-girlfriend Angela (Edda Köchl), there’s a melancholy in his intonation. He describes the city as a beacon, while the rest of America is painted as an interminably long, empty stretch of nothingness. After leaving the city, Philip feels as though he has wandered into a void, with location after location having the appearance of a fever dream. Only in returning to New York does Philip find peace.

Or so he thinks. Angela has surprisingly little sympathy for the suffocating nihilism that’s plagued him since leaving the Big Apple. “That happens when you lose all sense of yourself,” she says. “And you lost that a long time ago. That’s why you always need proof, proof you still exist.” Then, his former lover spurns him and, in a quietly saddening moment, we see them both as deeply isolated individuals, unsure how to deal with this little thing called life.

As Angela asks him to leave, Philip is bewildered, but she laments: “I can’t help you, though I’d like to comfort you… But I don’t know how to live either. Nobody has shown me either.” The future seems to bear down on these sorrowful souls. They are lonely and can no longer find solace in each other’s company. The city is shown to be an alienating force, an isolating entity; despite the throngs of people, it paradoxically intensifies this empty, impersonal atmosphere.

This is addressed more explicitly as a theme when Philip discusses the alienating sensation of living in the second half of the 20th-century: constantly engaged, yet simultaneously always disconnected. It’s a life lived at arm’s length. Media and consumerism are accused of being one of the many culprits: “The inhuman thing about American TV is not so much that they hack everything up with commercials, though that’s bad enough, but in the end all programmes become commercials. Commercials for the status quo. Every image radiates the same disgusting and nauseated message. A kind of boastful contempt. Not one image leaves you in peace—they all want something from you.”

To emphasise their terminal aloofness, the characters communicate in peculiar ways. Adult conversations are riddled with non-sequiturs; Philip, Lisa, and Angela barely listen to one another, solely interested in expressing emotions they struggle to articulate. This inevitably leads to frustration, melancholy, anger, or even desperation. The entire plot hinges on Lisa’s inability to communicate with her boyfriend, for whom she abandons her child. This fractured ability to share thoughts is depicted as the root cause of many societal ills.

However, Philip and Alice have what is probably the only normal relationship in the film: their unlikely friendship becomes the lifeblood of the story. In very real fashion, they open up to each other achingly slowly and it’s just at the end of the film that we feel as though they know anything about the other. We watch them grow accustomed to the shared company in authentic ways: when frustrated by their lack of progress in finding Alice’s grandmother, they hurl insults without fear of losing their comradeship—“Turd!” “Stupid cow!” “Fatso!” “Babyface!” Then, moments later, they are talking about their hopes for the future.

In addition to their journey, there is a shared dream that connects Philip and Alice—a quiet desire to find meaning, to conquer the looming nihilism that informs both of their worldviews. Of course, Alice is unaware that this is true of her; she is heavily dismissive of dreams as silly things. When Alice and Philip play hangman on the plane together, Philip reveals the word that the young girl has failed to guess: “Dream.” The nine-year-old is censorious: “Those words don’t count! Only things that really exist!”

It’s one of their most fascinating interactions. Why does a girl as young as Alice disbelieve in the reality of dreams? That they aren’t tangible entities, capable of being moulded and shaped? Alice possesses an air of jaded youth, unimpressed by everything, yet equally demanding that her wishes be fulfilled. Her chronic dissatisfaction stems from the time she was born: she’s inherited the gloom of a post-war world, one that lives in the shadow of the free-loving 1960s amidst the ever-present Cold War fear of nuclear annihilation. Because of this, dreams hold no true reality—one must focus only on what can be touched.

For a similar reason, Philip doggedly takes photographs with his Polaroid camera. These provide proof that he exists and that he has existed up until this point. As he tells Angela: “Taking Polaroids does have something to do with proof. Waiting for a picture to develop, I’d often feel strangely ill at ease. I could hardly wait to compare the finished picture with reality. But even comparing them wouldn’t calm me—the pictures never caught up with reality.”

This dichotomy—between the lived experience and the tangible evidence Philip requires to verify it—forms the core of his character development. He appears pessimistic about the future, unsure of what lies ahead; for this reason, he collects and silently clings to his past experiences. However, he discovers that he can only truly judge the depth of his experiences in relation to another person: Alice. Much like his Polaroid photographs, confirmation that something important is there just takes time; a little patience is needed to overcome such maladies of the heart.

Alice in the Cities is a film about both physical and emotional distance. The ending is a happy one, despite the ambiguous tone. As the pair stand on a train, looking out of the window, they both finally appear resolutely optimistic about their futures. Until now, the world has dwarfed them, making them feel tiny and painfully insignificant. But after their life-changing adventure, they look out expectantly at the world that awaits them.

This is a conclusion that teeters on the brink of great, lasting change. In different ways, they have both come of age. Their road trip was a literal and spiritual odyssey through a maze of urban jungles. Yet, in searching for towns, houses, and the relatives they contain, they found the one thing they least expected: themselves.

WEST GERMANY | 1974 | 110 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | GERMAN • ENGLISH • DUTCH

director: Wim Wenders.

writer: Wim Wenders & Veith von Fürstenberg.

starring: Rüdiger Vogler, Yella Rottländer, Lisa Kreuzer, Edda Köchl & Ernest Boehm.