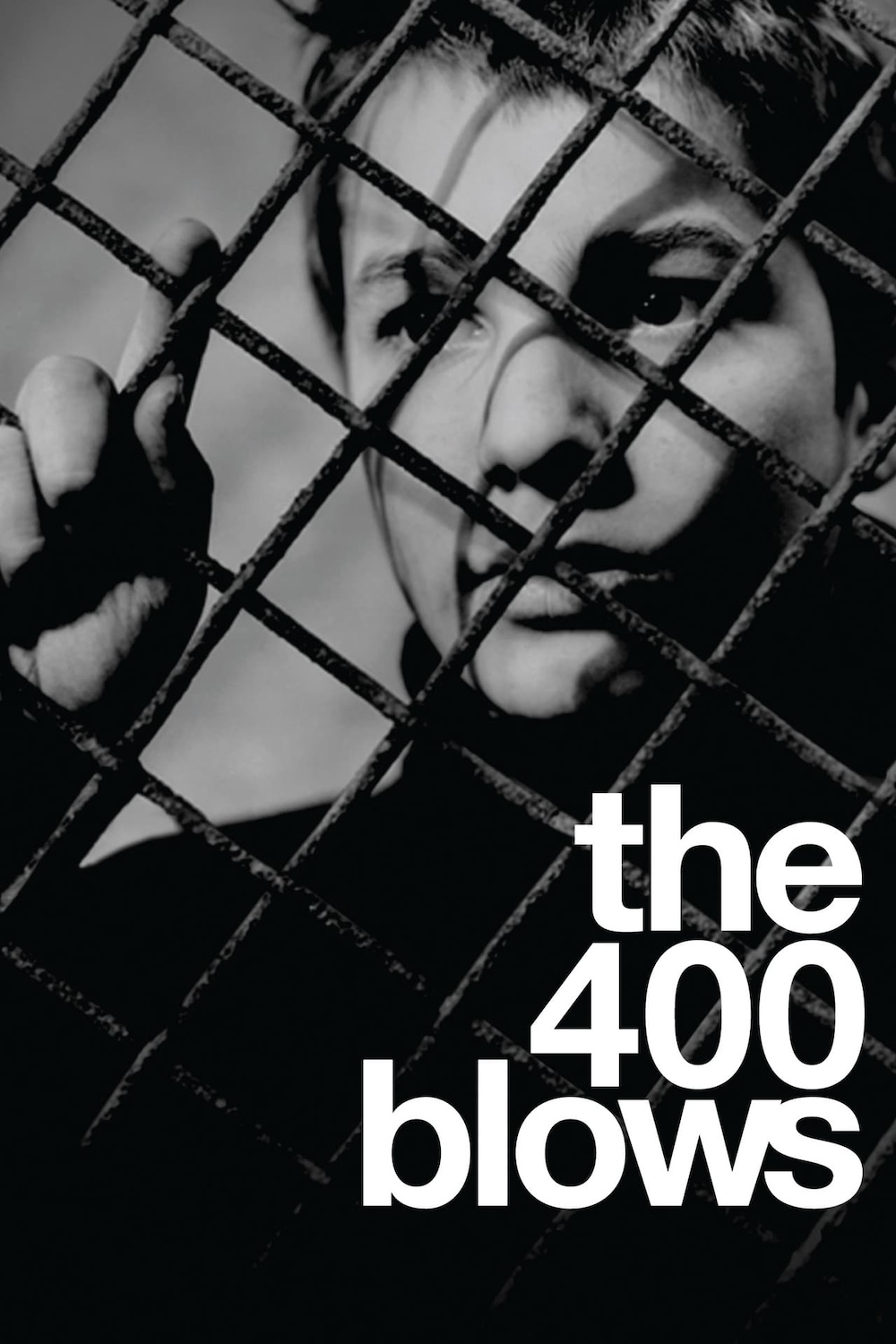

THE 400 BLOWS (1959)

A young boy, left without attention, delves into a life of petty crime.

A young boy, left without attention, delves into a life of petty crime.

Paris twirls in constant motion. Footage obtained from a moving car conveys the perspective of a young boy gazing upon his home city for the last time as a child: he’s being taken away, sent to an observation centre for troubled youths. The opening shot symbolises a life that has been spent almost entirely in locomotion, running, travelling, or escaping from one place to another. Our story depicts the incongruity of childhood innocence within the real world, becoming a moving portrait of adolescent angst.

Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows / Les quatre cents coups isn’t only widely considered his best film, but also one of the finest films of the 1950s. It’s a remarkably prescient piece of work, anticipating the cultural movements of the following decade, particularly the vehement unrest of the oppressed youth. In the 1960s, hearts and minds which were left unsupported by the system they sought to break free from it, with Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud) becoming the iconic visage of this emerging generation.

When we first meet Antoine, he’s one of many mischievous boys in his class. School is depicted as both an autocratic regime and a training ground for adolescent frivolity: here, young males will learn how to push the boundaries of authority. A world of comedy exists behind the back of a belligerent teacher, with the hilarity of the transgression and the danger of detection being inextricably linked; these boys are learning how much fun it is to break the rules.

For most children, this is confined to the classroom, providing a relatively safe environment in which to test their newfound contempt for authority. However, Antoine’s disobedience extends far beyond that, spilling over into his home life and onto the streets of Paris. He engages in petty theft, pathological lying, and chronic truancy, all in a bid to avoid the repercussions of his actions.

Truffaut wisely chooses not to portray Antoine as a villain or a malicious delinquent. He’s simply a child in desperate need of guidance, an understanding and sympathetic ear. Throughout the film, adults bemoan the fact that Antoine doesn’t confide in them, yet they are never shown providing him with the opportunity to do so. They explain, direct, and instruct, but rarely listen.

In this respect, Truffaut astutely positions Antoine as a peripheral figure in the lives of those around him. He’s not even the central character in his own life. To his teacher, he’s merely one of many daily annoyances. His stepfather, Julien (Albert Rémy), constantly talks about work and his forthcoming promotion, while reminding Antoine to be considerate of his mother and her limitations.

Arguably, her limitations are at the root of Antoine’s maladjustments. His mother, Gilberte (Claire Maurier), is utterly cold towards him, often resorting to verbal abuse. She displays little or no maternal instinct, and her first scene establishes the family dynamic perfectly: returning home from work, she berates Antoine for forgetting a grocery item, belittles his intelligence, and then instructs him to leave and rectify his mistake. She never inquires about his day or his feelings; Antoine is little more than a servant for his own mother.

As Antoine curls up in a sleeping bag on a small sofa, it’s clear he’s been neglected for a long time; this existence is all he’s ever known. As we soon discover, Antoine never knew his biological father and was nearly aborted by Gilberte. Sent to live with a wet nurse, then his grandmother, Antoine finally returned home to live with his mother and stepfather at the age of eight. His has been a life of constant upheaval and incessant turbulence, an infant on the run, alone in the world from the very beginning.

However, Truffaut doesn’t divulge this backstory early on. Impressively, he garners our sympathy for Antoine solely by conveying his desires: to be truly alone, away from that loud, nightmarish flat and those who punish him. “I want to live my own life,” he intones to his friend, resolving to run away from Paris. He dreams of living by the seaside and setting up a boating business, bewitched by the prospect of no one bothering him in his own private Arcadia. Being on his own is not a punishment, but rather represents a chance at solace.

Truffaut expertly positions the crushing weight of reality in stark contrast to his boyhood dreams. Instead of living the life of a sun-drenched vagrant, he sleeps in a freezing printing press, stealing milk to keep himself fed as the rest of Paris slumbers in their beds. As the city begins to stir, awakening to the morning light, Truffaut captures the solitary wanderings of a troubled child with gorgeous cinematography. As he meanders through the deserted streets, cinematographer Henri Decaë transports you back to the times of your own adventurous, searching childhood.

This is arguably the film’s greatest strength: it’s a hypnotic ode to the period in one’s life when we’re at our most vulnerable and misunderstood, when we form our mindset about how we will survive in a world that seems intent on conquering us. In such times, the ability to fight back and avenge the wrongs done to you is paramount, demonstrating that one will not be held down or conform to the pressures of a disinterested society; recalcitrance becomes an admirable trait in Truffaut’s The 400 Blows.

However, our auteur doesn’t shy away from portraying the consequences of such intractable behaviour, demonstrating where a life spent in rebellion on the margins of society ultimately leads. Antoine’s blissful myopia is symptomatic of his lack of loving counsel, resulting in his growing reliance on theft. What begins as a relatively negligible shoplifting habit gradually escalates into genuine criminality: Antoine is spiralling into an existence as a lifelong degenerate.

The score does a fantastic job of capturing Antoine’s inner turmoil. It’s a simple yet poignant theme that encapsulates the aimless, anxious questing of youth—a melody written for those trying to forge their way in a world that doesn’t want them in it. It’s magical, yet melancholic, imparting the sensation of childhood dreams being trapped and diffused by a society that makes their achievement impossible. Aspirations become feeble pleas.

Truffaut crafted an odyssey of adolescent disobedience. Any coming-of-age story released after 1959 owes a great debt to The 400 Blows, a French expression for our teenage inclination to live recklessly. Ava (2017) picks up right where Truffaut left off, portraying the life of a 13-year-old girl who rebels indiscriminately upon discovering she will soon go blind. Even last year’s The Holdovers (2023) demonstrates a similar fondness for the teenage desire for rebellion, showing that it’s a universal theme we’ll surely never tire of.

The French New Wave director paints a picture of the unruly and transgressive proclivities of young adults in the most touching and cinematic of ways. Ecstatic at the success of their daring mission, two childhood friends leap through a congregation of pigeons, which take flight in surprise as the boys dash away with their illicit typewriter. They pilfer alcohol wherever they can and puff on cigars like distinguished gentlemen. And the running—is there a better way of visually encapsulating the urgency of youth?

Antoine’s running becomes a leitmotif in its own right. It symbolises his desire to escape but without a specific destination in mind. He only seems content when he’s in motion, as evidenced in the film’s final sequence. Driven by a sudden urge to flee, Antoine turns and sprints towards the beach. Then, mystifyingly, he begins racing towards the shoreline.

In what is arguably one of the most iconic endings in cinema, Antoine turns and gazes into the camera. It’s a haunting image of adolescent uncertainty, of the teenage angst that’s almost impossible for the young to articulate fully. There’s so much that feels incomprehensible that Antoine can only set his sights on the horizon. It’s solely the saltwater wetting his feet that reminds him of his limitations, drawing a misunderstood dreamer back to reality. In one perfect moment, Antoine was free, but he’s now burdened once more with the question: now what?

It’s a problem that has dominated his whole life. As such, Truffaut concludes his story exactly where it begins in earnest. However, by denying us knowledge of what will happen next for young Antoine, he compels us to share his predicament. The precariousness of his future hangs heavily over him and, as the credits roll, it weighs down on us too. Truffaut seems to ask his viewer: “Where were you when you first stared down the barrel of your own life?” Antoine Doinel was standing on a beach, wondering where he should run next.

FRANCE | 1959 | 99 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | FRENCH • ENGLISH

director: François Truffaut.

writers: François Truffaut & Marcel Moussy.

starring: Jean-Pierre Léaud, Albert Rémy, Claire Maurier, Guy Decomble, Patrick Auffay & Georges Flamant.