AFTER THE HUNT (2025)

A college professor finds herself at a personal and professional crossroads when a star pupil levels an accusation against one of her colleagues and a dark secret from her own past threatens to come to light.

A college professor finds herself at a personal and professional crossroads when a star pupil levels an accusation against one of her colleagues and a dark secret from her own past threatens to come to light.

Is any filmmaker today working at a frequency as consistent as Luca Guadagnino? From the moment Call Me By Your Name (2017) swept the film world, the iconoclastic director has not let up even a single second of his hot streak. He’s proven that he can do virtually any task set for him—starting with the pivot he took into Suspiria (2018), reimagining Dario Argento’s seminal giallo fixture into a postmodern horror treatise on wartime history and political power.

From there, Guadagnino’s voice has only expanded in scope. Bones and All (2022) proved his proficiency in retooling the conventions of the YA genre into the realm of visceral brutality. Challengers (2024) instantly hit its stride as perhaps one of the greatest sports films ever made, providing riveting psychosexual tension to the tune of a fiercely polyamorous tennis rivalry. Queer (2024) and its hallucinatory adaptation of William S. Burroughs’s novel at once taps into its unique frequency of gay male loneliness while metatextually peering into Burroughs’s harrowing inspirations for the novel’s conception.

So when Guadagnino’s latest film, After the Hunt, begins with an opening credit font choice that explicitly homages the work of Woody Allen, it ostensibly appears that he’s provocatively taking on the ripple effects of the post-MeToo era. On that note, these are dire, richly sensitive times to be an artist, and it’s becoming clearer by the second that countless recent releases are rising to the challenge of meeting the moment.

Ari Aster’s Eddington (2025) remains the most accurate cinematic diagnosis of America’s national nightmare, reaching back to COVID-19 as the primary inflection point. Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia (2025) dives into the tragic calamities of terminally-online conspiratorial thinking and the inhumane avarice of top-1% billionaires. Kathryn Bigelow’s A House of Dynamite (2025) presents a wide-ranging vision of a competent system completely failing to stop a nuclear attack, almost as if to say, “if they can’t do it—how are we supposed to?”

With After the Hunt, it’s not initially clear what angle Guadagnino and screenwriter Nora Garrett want to approach our modern times from. But as its tapestry of academia, accusation, and accountability unfolds, it slowly becomes apparent that privilege is the shadow looming large over its narrative. The characters found at the centre of Guadagnino’s latest, tied to a singular Yale University philosophy class, benefit from enormous privilege from either their status or their demographics—and for some of them, even both.

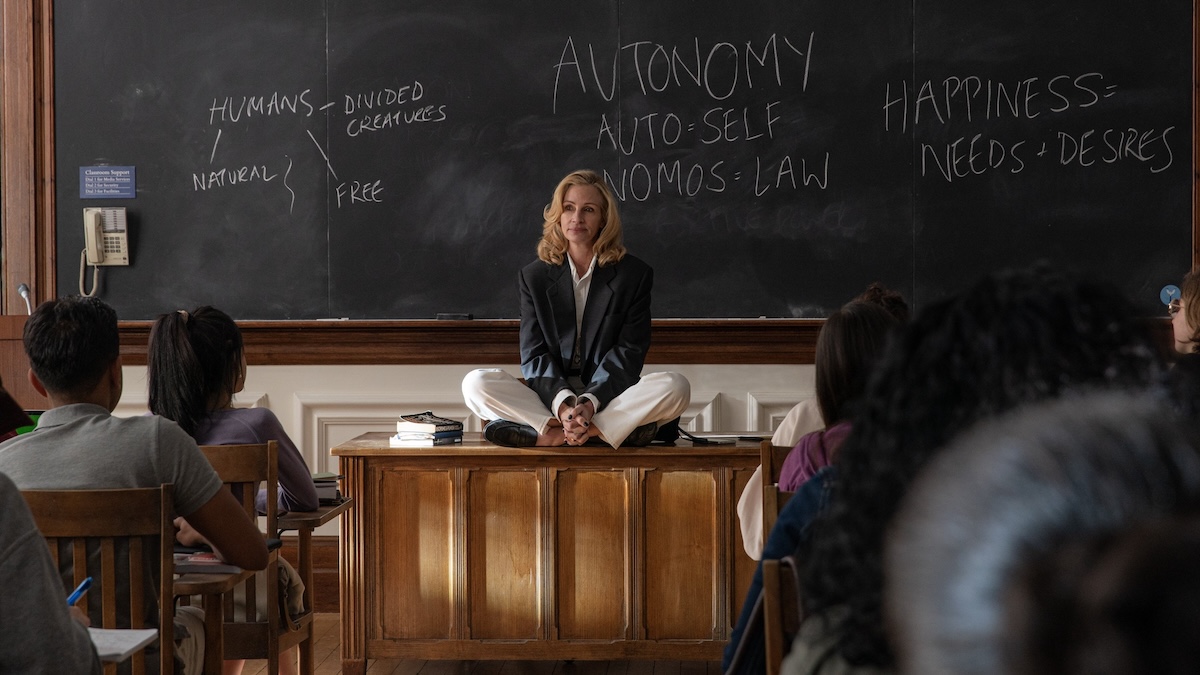

We get our first proper glimpse of them in their usual habitat; an alcohol-laden dinner party held by Professor Alma Imhoff (Julia Roberts) and her therapist husband Frederik (Michael Stuhlbarg), with fellow Professor Hank (Andrew Garfield) and PhD student Maggie (Ayo Edebiri) in attendance. Several things are meaningfully gleaned from their initial conversation. Alma and Hank are both up for tenure, vying for the permanence it lends them, putting them in tenuous competition while remaining vaguely flirtatious with each other. Maggie and Alma are ideologically in lockstep over the unfair treatment of women in academia. Alma has risen past that to her current position, and Maggie aspires to meet that example, even as she remains the only Black person in the room.

Hank has a long history of remaining flirtatious with his students as well; Maggie, for now, appears to be the latest among them. And Frederik has very little sympathy for Maggie, who, as we eventually find, is the daughter of two incredibly wealthy donors to Yale. He sees her as the polestar of nepotistic academic mediocrity, and jabs at Alma’s seemingly unconditional support of Maggie based solely on the admiration she receives.

Already, we see the skeletons in the cupboard. One of them is more literal, as Maggie heads to the bathroom and stumbles upon a hidden letter of Alma’s, perhaps kept in a slightly too contrived location, but one of eventual significance regardless. The sheer prevalence of alcohol in the party proves to be a visual motif of its own; nearly every scene with Gen-X-aged characters will have a bottle of some kind lingering in the periphery, and in small batches, we see Alma struggling with sharp, debilitating stomach pains. Even as she seeks the help of psychiatric counsellor Kim (Chloë Sevigny) for said condition, they’ll still make visits to nearby bars for the sake of getting a drink together. And even here, it becomes clear just how much Alma is willing to hide from Kim, as much as Alma confides in her about her health and situation.

But the clearest among them—Hank’s seeming fondness for Maggie—rears the most immediate, ugly head of them all. Maggie turns up to Alma’s doorstep the very next night in the rain, telling her that immediately after the party the previous night, Hank and Maggie went to her place, and Hank sexually assaulted her. Hank’s instinct when confronted by Alma is to deny it, levelling an accusation of his own (that Maggie is flagrantly plagiarising her thesis paper for the class, using her accusation as a diversion), but soon launches into a barely-restrained misogynistic tirade against Maggie driven by rage and desperation.

Thus begins After the Hunt’s saga of accountability—one where the privileges of all involved create an unfurling, fascinating cascade of academic controversy. It’s an ambitious evisceration of privilege in higher-level academia; how laden it is with politicking of its own, and how it creates an environment where image-consciousness overshadows authenticity. It’s also a nuanced examination of how membership in underrepresented communities is not the be-all-end-all of oppression, daring enough to comprehend how class and money dictate the flow of social power. And it understands a pivotal generational gap in how trauma is dealt with in zones of privilege and pretension, either via self-destructive suppression or outwardly overwrought expression.

Much conversation and polarisation has been made of this film being some kind of reactionary centrist statement, or a provocation that never follows through on its promises. But viewing the film through this lens of privilege is the unifying factor here, one that calcifies its series of revelations as being a cohesive part of a clear intention. How are we meant to see generational differences in how a traumatic event is processed? How is the comfort of privilege its own unifier across those differences? What happens when people working solely in self-interest are faced with serious institutional and moral failure? Garrett’s script is driven less by ambiguity than it is by the collision of these disparate generations and backgrounds, shown by how each of the primary characters holds some kind of tenuous alliance with at least one other person.

Alma and Frederik’s marriage is too outwardly cordial, too marred by bouts of sardonic passive-aggression to be genuine—but they steadily find some union in their growing resistance against Maggie’s overzealous desire to morph her trauma into a cultural moment. Maggie and Alma, as mentioned, have a real unity over their shared experience as female academics, but their racial divide is one facet of the gulf that grows between them—and the skeletons in Alma’s cupboard make it clear that, on multiple fronts, she’ll never be the role model that Maggie wants her to be. And Maggie, on her own, is so overtly keyed into the optical realm of performative leftism that it defines every detail of her response to what she’s accused Hank of, down to how she wields her relationship with her trans partner, Alex (Lio Mehiel), and how she deflects from every plausible accusation of mediocrity lobbed her way.

Formally speaking, After the Hunt is Luca Guadagnino’s least outwardly intensive effort. Those looking for the ricocheting nonlinear rhythms of Challengers or the psychedelically cosmic immersions of Queer will likely find themselves surprised by just how much After the Hunt resembles a straightforward chamber piece. And yet, that’snot to say there aren’t any fascinating gestures—Guadagnino still makes an effort in places.

The occasional use of POV shots deviates from a more typical, steady-tracking-shot visual language, and sonically, the emergence of a ticking clock amid near-total silence is an interesting source of tension. Yale’s campus is ripe territory for some potent composition by cinematographer Malik Hassan Sayed, with some of the university’s distinct buildings and establishments—alongside the Imhoffs’ deeply bourgeois apartment—being framed in all their upper-class, richly-endowed splendour.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross are also here working on a more downscaled scope for their soundtrack, in stark contrast to the propulsive techno beats of Challengers or their unleashing as Nine Inch Nails for Tron: Ares (2025). Here, the emergence of a recurring, halted piano motif becomes gradually more unsettling with each incidence—and Reznor and Ross are as consistent as usual when the film provides a moment for their more intense soundscapes to erupt.

No film this oriented around its ensemble works nearly as well without some concerted efforts from its cast to enliven the dynamics between their characters. Edebiri’s work as Maggie is yet another demonstration of her stellar range, a total mirror image from her work in more comedic fare like Emma Seligman’s Bottoms (2023), where she now gets to embody the entitled corruption of ‘woke’-ist ideals via the near-insurmountable privilege that Maggie’s parents lend her amid this heavy personal crisis.

Garfield’s portrayal of Hank as a man teetering on the edge is a smart casting choice for someone whose previous roles have often coasted on their charm and effortless charisma. Here, he gets to deliver how that charm can be utilised for more manipulative and perhaps even violent ends—via a man so desperate for tenure that this destabilising moment spirals him right off-balance. Garfield keys into how Hank is never quite what he seems at any point, prone to outbursts even as he easily draws people into his orbit.

Stuhlbarg has to be the comedic highlight here. His portrayal of a man who falsely believes himself above the purview of this institutional crisis, while still too loyal to a marriage that is clearly on ice, lends a bitterly sarcastic edge to his humour. There’s one scene in particular where the repeated threat of his knowing intrusion into a particularly tense exchange between Alma and Maggie makes for a strikingly funny moment of physical comedy as he walks in and out of a room with increasingly careless gusto.

It’s strangely Roberts’s role that proves to be a fascinating link in this chain, where Alma becomes perhaps too unreadable for her own good, and where the betrayals she inflicts on those around her aren’t necessarily felt. The character’s incredibly optics-conscious, especially when it comes to the things she dedicatedly hides, as well as how she establishes tenuous allegiances with Hank and Maggie in order to preserve her own hide, but as thorny as such a role is, Roberts plays that outward obscurity up perhaps to a bit of a fault, too lacking in cracks in the mask.

One thing about the timeliness of this film is clear. As American educational institutions steadily begin to come under fire by the current administration’s attacks against free expression and education, high-profile universities are forced to choose between capitulating for the sake of their funding or living up to the ideals of their founding. It’s a choice that requires their leaders, cut from various cloths, to see past the privilege lent to them for so long. And yet, many of them are not making the choice of long-term ideological survival. Rather, nearly all of them have abandoned their founding principles and ideals, giving in to despots to preserve their own hides and save every last penny of their endowments at the expense of their students.

In the context of that, After the Hunt is an oddly enriching film. It has some gaps in its expansive, ambitious narrative tapestry, but its deconstruction of privilege in neoliberal academic spaces has enough bite to last an impact. And its interrogation of privilege in universities—where the presumption of knowledge and educationpermits people to turn away from their biases, consciously or not—allows the film to understand how it affects people of different generations.

These institutions, intended for authentic education and enrichment, are becoming arenas of their own. The most prestigious among them breed faculty ignorant of how they wield or aspire to the permanence of tenure, and create students who believe themselves enlightened despite the coyness many of them demonstrate about the ability to afford the costs of attending these schools. We would be remiss to outright dismiss a film willing to deconstruct this privilege as reactionary—even more foolish to claim that it’s signifying nothing whatsoever. It’s a confrontation like this that contributes to how filmmakers this past year have dealt with our dire present moment. Guadagnino and Garrett are willing to stare down people who respond to moral failure with nothing but privileged self-interest, and daring enough to tell them they provide nothing of any meaning or significance.

USA • ITALY | 2025 | 138 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Luca Guadagnino.

writer: Nora Garrett.

starring: Julia Roberts, Ayo Edebiri, Andrew Garfield, Michael Stuhlbarg, Chloë Sevigny & Lio Mehiel.