THE KILLING OF A CHINESE BOOKIE (1976)

A proud strip club owner is forced to come to terms with himself when his gambling addiction gets him in hot water with the mob, who offer him only one alternative.

A proud strip club owner is forced to come to terms with himself when his gambling addiction gets him in hot water with the mob, who offer him only one alternative.

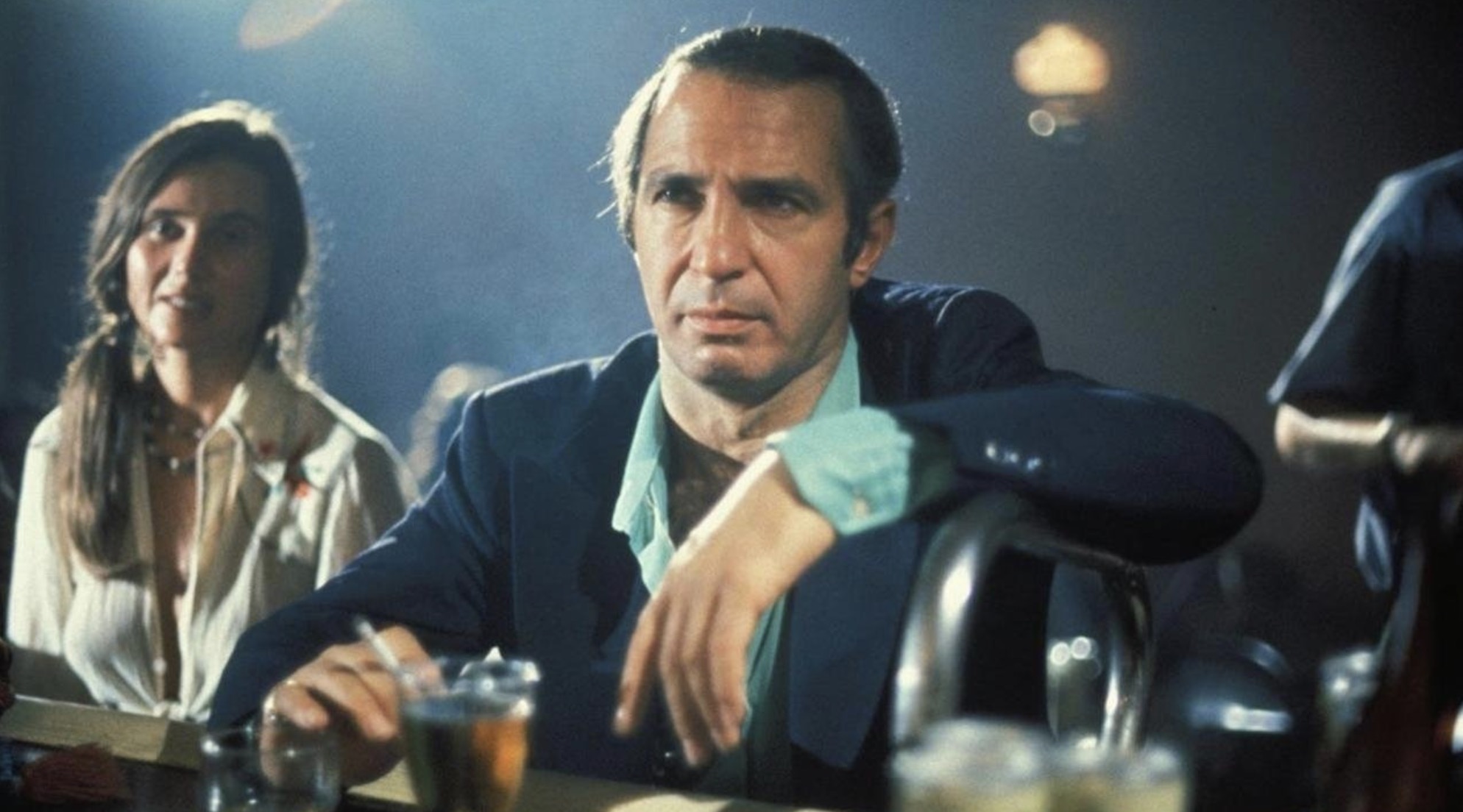

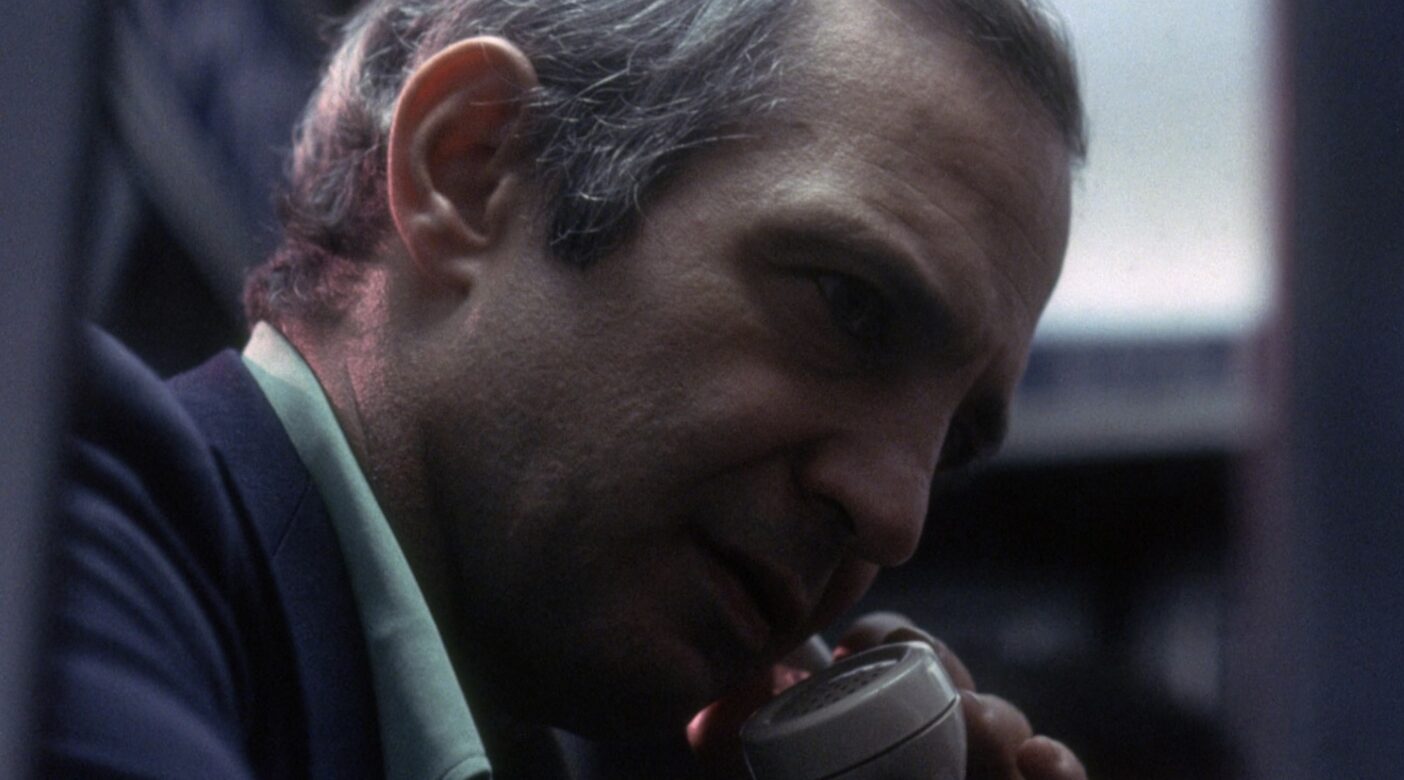

In John Cassavetes’ The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, protagonist Cosmo Vitelli (Ben Gazzara) is a man enlivened and enraptured by a dream. It’s a dream that no one but him respects or understands, yet that does little to dim his hopes. One need only observe Cosmo’s wry smile in times of trouble—as much a symbol of charm as delusional arrogance—to recognise that others’ opinions matter little to him. This outlook pits him against not just those around him, but humanity itself. Other people don’t recognise his dreams, and he can’t recognise theirs; he’s simply too self-interested.

He pins his hopes on a strip club on the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles. For the strippers, it’s work; for the patrons, it’s pleasure. For Mr Sophistication (Meade Roberts), the host of the club’s routines, it’s showmanship. For Cosmo, it is all of these, but more importantly, it’s where he watches his dreams play out. The scantily clad women might as well be there by accident. He is at home in the club’s shadowy corners, alive under its lighting, lost within the cigarette smoke snaking into cracks in the furniture. He’s a fixture of the venue. You might struggle to spot him in the smoky, half-lit room, but you can trust he’ll be there, silently mouthing the words to the routines, praying it all goes to plan.

Why, exactly? No one is there for artistry. Granted, there’s a heightened pleasure for the clientele in having the objects of their lust teased out rather than revealed at once, but the execution matters little. Mr Sophistication and Cosmo might assist with the club’s upkeep, but they’re hardly essential to unlocking the patrons’ pleasure. Cosmo isn’t interested in the customers or his workers, even if he holds no animosity towards them. He is constantly searching for, or chasing, that ultimate spectre of his desire: perfection.

It isn’t enough to be rich, successful, or envied; one must always be on the lookout for something greater. Perhaps that’s why Cosmo is a successful businessman but a terrible gambler: he’ll never quit on himself. Just after handing over the final payment of a years-long debt, he takes out an exorbitant sum and gambles it all away. Back at square one, he owes local mobsters $23,000, and this time they aren’t interested in a simple payout. They want a quick resolution: if he kills someone for them, the debt is erased.

The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is a marvel, regardless of whether it excites. It scoops out the guts of the well-worn crime genre, leaving a hollowed-out husk of the American Dream in its place. There’s a haunting quality to the film, whether we’re watching Cosmo languishing in his club, charmed by a vision only he understands, or wading through unknown territory on an insane late-night journey to take a life. Cosmo is a lonely, sad figure, yet he’s so unaware of this that you wonder if he’s fulfilled after all. He seems perfectly fine as an island; at no point does he ask for love or respect. It is indifference, not hesitance, that keeps him from seeking affection.

All Cosmo needs is an opportunity. With that, he’ll do everything in his power to succeed. Success isn’t guaranteed, but that’s the point. Without the risk of failure, Cosmo would crumple. He is surrounded by lust, jealousy, beauty, and violence, yet none of it means anything to him. He’s lost on others, they’re lost on him, and no one cares to change that. It’s a unique tragedy. While stories of the American Dream have existed for over a century, the theme feels prescient in Cassavetes’ hands. Fifty years later, the film has lost none of its relevance.

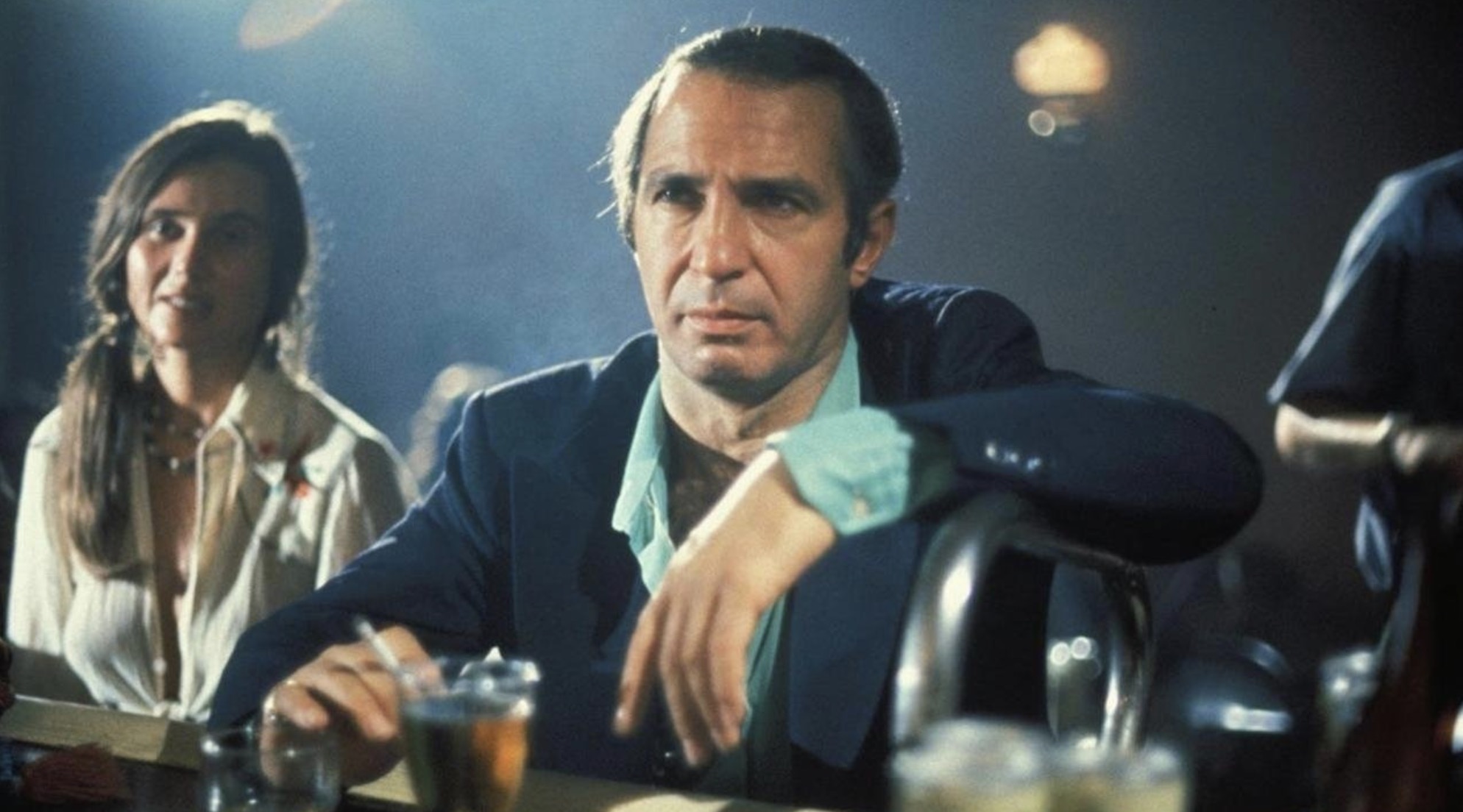

The mobsters’ target is Benny Wu (Soto Joe Hugh), a high-ranking Triad boss—something Cosmo likely suspects but isn’t told before the hit. Cassavetes takes his time with these sequences, whether witnessing Cosmo wander through his familiar stomping ground or seeing him in alien surroundings. Wherever he is, he’s buoyed by charm and self-reliance. He could probably make a living in hell, should he be so unfortunate. Gazzara oozes a mixture of charm and arrogance; you can’t help but be simultaneously impressed and grated by his self-satisfied grin.

Where the film falters is in its attempt to map out the loneliness of Cosmo’s life. It creates emotional voids that hamper the viewer’s investment just as much as Cosmo self-sabotages his own relationships. You understand Cosmo after just a few minutes of watching Gazzara’s routine; once he’s out of his comfort zone, you know him completely. Like many sleazy, self-assured characters, his ultimate con is an unconscious one, effortlessly winning the viewer over. You want him to succeed because you cannot root for “The Man” and its violent enforcers to punish someone who bets everything on themselves. But that isn’t the same as caring desperately for him—a tall order the film doesn’t quite achieve.

Like Cosmo, the film languishes in its own ambience, offering an eerily existential and coolly detached rumination on a country of dreamers and the misfortune that follows their dreaming, all wrapped in one solitary soul. That distance repels deep empathy, yet it’s exactly what binds the film’s existentialist core.

Cosmo admires his workers, has a girlfriend, Rachel (Azizi Johari), and refers to her mother, Betty (Virginia Carrington), as “Mom”. Yet nothing meaningful is ever shared between him and someone else. Cosmo is so rarely sincere, but even when he is, this protagonist’s words are overlooked. There is a grain of tragedy here, but it’s mostly expressed as a detached disaffectedness that enraptures the film.

That doesn’t mean it isn’t a pleasure to watch Cassavetes navigate a crime film the only way he could. His mobsters conduct cordial conversations in mysterious buildings, dealing in receipts and financial documents. They’re always classy, even if they are fundamentally anything but. They’re performers too, lost in the intersection between acting and staying true to themselves.

You can sense this in the film’s central theme. Gazzara reflected that Cassavetes—a dreamer committed to his art and disappointed by its reception—must have seen himself in Cosmo. Where that connection begins and ends cannot be quantified. In the fuzzy ambience between these spaces, where nothing is certain and everything is a gamble, The Killing of a Chinese Bookie is briefly entrancing.

USA | 1976 | 135 MINUTES • 109 MINUTES (1978 RE-RELEASE) | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: John Cassavetes.

starring: Ben Gazzara, Timothy Carey, Seymour Cassel, Morgan Woodward, Azizi Johari, Robert Phillips & Meade Roberts.