HOUSE PARTY (1990)

Kid decides to go to his friend Play's house party, but neither of them can predict what's in store for them on what could be the wildest night of their lives.

Kid decides to go to his friend Play's house party, but neither of them can predict what's in store for them on what could be the wildest night of their lives.

The vibrancy of Black youth culture has long existed in cinema, yet for much of the late-20th-century, it was denied narrative seriousness or cultural autonomy. Urban adolescence was rarely treated as a subject worthy of exploration, functioning primarily as an afterthought rather than a lived experience. During the Blaxploitation era of the 1970s, Black teenagers appeared more frequently, but Hollywood executives reduced them to hustlers, criminals, or streetwise archetypes designed to appease white audience expectations.

The following decade did little to correct this distortion. Directors like John Hughes (The Breakfast Club) and Cameron Crowe (Fast Times at Ridgemont High) began mythologising white suburban adolescence as the universal teenage experience. As Black youth became further marginalised, Spike Lee emerged as a disruptive force. With She’s Gotta Have It (1986), he depicted teenagers not as stereotypes, but as complex individuals shaped by history and community. Lee challenged the industry’s assumptions about mainstream appeal and established a framework that allowed Black filmmakers to represent their youth without studio interference.

It was within this movement that writer-director Reginald Hudlin produced his short film, House Party (1983), while at Harvard University. Years later, Hudlin and his brother Warrington expanded it into a feature-length screenplay. Although the project was initially conceived for the rap duo Will “Fresh Prince” Smith and Jeff “DJ Jazzy Jeff” Townes, New Line Cinema hesitated. The studio was ultimately convinced when Janet Grillo (Pump Up The Volume) pitched the idea as a “Black John Hughes film”. Persuaded by Hip-Hop’s momentum and the commercial viability of Black filmmakers, the studio agreed to fund it.

However, the Hudlin brothers didn’t anticipate how House Party would prove the potency of placing Black youths at the centre of a universal experience. It reframed urban culture, diverging from Hollywood’s fixation on crime to showcase a relatable depiction of youth that crossed racial boundaries.

When Play’s (Christopher Martin) parents leave for a holiday, he seizes the chance to cement his status as a burgeoning rapper by hosting a party. His best friend, Kid (Christopher Reid), is eager to attend the ultimate rendezvous, but his enthusiasm is curtailed after an altercation with a bully named Stab (Paul Anthony). When the incident is reported to Kid’s loving but authoritarian father (Robin Harris), he forbids his son from leaving. Despite being grounded, Kid can’t resist the lure of social validation and a potential romance with Sydney (Tisha Campbell). He sneaks out while his father sleeps, but what should be a straightforward trip becomes a perilous journey across the neighbourhood. Kid must evade a vengeful trio of bullies and a pair of racist police officers prowling the streets.

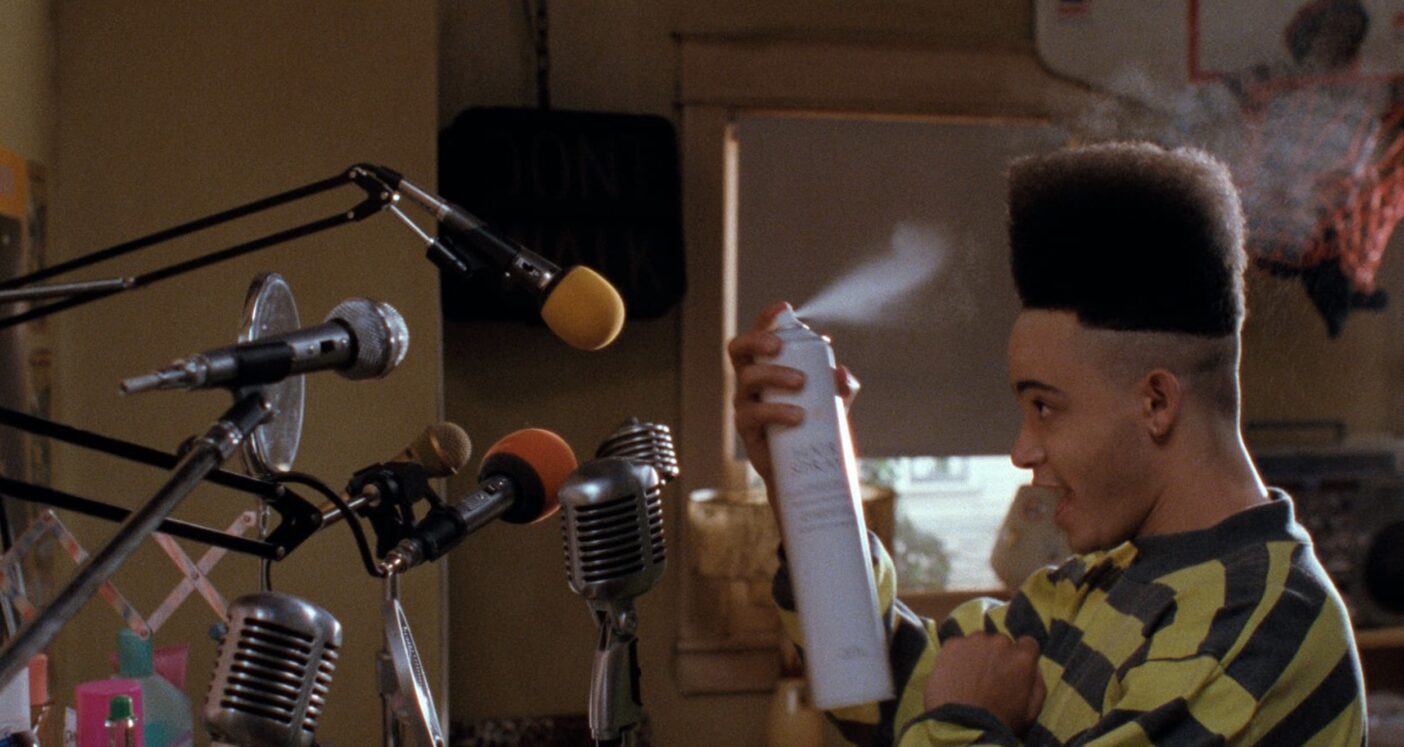

The entire ensemble shines as brightly as their colourful outfits, but the film’s energy derives primarily from Christopher Reid’s performance. Sporting a towering haircut that would make Henry Spencer in Eraserhead (1977) envious, Kid’s greatest concern is surviving the night unscathed. Resisting the temptation to lean into caricature, Reid embraces the character’s impulsiveness with sincerity. Whether he’s smooth-talking his way out of confrontations or deploying earnest seduction techniques, his affable demeanour is naturally likable. His screen presence radiates a disarming earnestness that serves the material well.

Ensuring the momentum never subsides, a dependable collection of seasoned comedians fills the roster. The heart of House Party is the late Robin Harris as Kid’s widowed father. As the perpetually aggrieved patriarch, Harris commands every scene with impeccable timing and scathing comedic authority. Though he passed away shortly after the film’s release, his presence endures. Elsewhere, the late John Witherspoon delivers a characteristically hilarious turn as an enraged neighbour adamant that his sleep won’t be interrupted. Whether he’s complaining about “Public Enema” or forgetting the police’s phone number, he practically steals every scene. Alongside his appearances in Talkin’ Dirty After Dark (1991) and Friday (1995), this performance functions as a preview of the cantankerous brilliance that made him a fixture of 1990s comedy.

Though Hudlin’s screenplay is deceptively straightforward, it is underpinned by a genuine attentiveness to urban adolescence. Black representation was still recovering from an endless cycle of archetypal fantasies typified by Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971). House Party emerged as the antithesis of Blaxploitation, positioning itself in a lineage traceable to Cooley High (1975) and Do the Right Thing (1989). Hudlin rejects portraying his characters as symbols, opting instead for fully realised teenagers contending with the mundanities of youth. Whether it’s Play’s performative bravado or Kid trembling at the prospect of parental discipline, the familiarity of these moments lends them verisimilitude. In presenting this nuanced portrait, Hudlin destabilises racialised boundaries, allowing his characters to be just as relatable as the privileged white teenagers in John Hughes’s fables.

This sincerity is why an unassailable spirit permeates the 100-minute runtime. Hudlin never condescends to his characters, and this respect was reciprocated by the cast. Allowing them to draw from their own experiences generated moments of rare authenticity. The iconic dance sequence emerged organically because A.J Johnson (Sister Act) insisted that a credible party required a dance battle. “All I knew at parties were dance battles,” she recalls. What begins with Kid demonstrating a manoeuvre soon evolves into the scene that perfectly encapsulates the film’s ethos. As the action moves to the heart of the party, it stages Kid ‘n Play’s showboating precision against the fluid confidence of Sydney and Sharane. It’s an intoxicating exchange that exemplifies Hudlin’s commitment to representing Black adolescence as inventive, communal, and playful.

The film is filled with fantastic musical cues. Hudlin weaves tracks by Public Enemy and Eric B. & Rakim through the narrative. Equally deserving of recognition are Kid ‘n Play themselves; their talents extended well beyond their screen personas. Their single “Funhouse” dominated the Rap Billboard charts and marked a pivotal moment in Hip-Hop’s expansion into the mainstream. Crucially, the duo’s competitive verses introduced audiences to the concept of the rap battle. Decades before Eminem captured the world’s attention with 8 Mile (2002), House Party accomplished something radical. Beneath its comedic trappings, it legitimised Hip-Hop as a performative art form worthy of cinematic spectacle.

House Party is imbued with youthful romanticism, but it remains acutely aware of harsher realities. Threaded through the buoyant dance moves is a surprisingly sober social conscience. The recurring presence of antagonistic police officers underscores the threat of institutional violence. Similarly, Play’s remarks about dating a girl from “the projects” expose class prejudices and internalised stigmas. These themes are dark, but Hudlin refuses to allow them to overwhelm the freewheeling momentum. Instead, his social critiques are woven into the narrative fabric, counterbalanced by a celebration of simple pleasures. Rather than ignoring inequity, the film affirms the importance of the escapism found in friendship.

There’s no denying the iconic status the film has accrued, but it’s not without flaws. Through a contemporary lens, its treatment of sexual assault and homophobia is troubling. One sequence, questionable even in the 1990s, has aged poorly: while in custody, Kid narrowly avoids what is unmistakably implied to be a sexual assault. This is a significant low point.

Furthermore, in an attempt to intimidate inmates, Kid launches into a rap that ridicules gay people. It may seem inevitable that Hudlin would lean into the crude humour of the era, especially in a directorial debut. Yet, these attitudes shouldn’t be brushed aside with a nostalgic shrug. What was once dismissed as harmless irreverence now registers as regressive. Acknowledging these imperfections shows how far we’ve come regarding acceptable standards. Hudlin himself has since expressed regret, stating, “There’s nothing worse than offending people who you don’t mean to offend.”

These missteps are minor stumbles in an otherwise assured debut. House Party succeeded far beyond expectations, emerging as a commercial triumph. In an era of white-centric teen comedies, critics celebrated its unapologetic Black sensibilities. It repudiated the assumption that these stories lacked mass appeal, grossing $26M against a modest $2.5M budget. Its popularity on home video cemented it as a cultural touchstone, establishing a franchise and propelling Hudlin’s career to films like Boomerang (1992).

In the wake of this success, studios responded with a surge of projects rooted in Black culture. New Line Cinema backed works like Deep Cover (1992), Menace II Society (1993), and Friday. This momentum influenced other studios to finance a new generation of filmmakers, resulting in John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood (1991) and Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever (1991). While House Party didn’t single-handedly instigate this renaissance, it provided a viable blueprint: Black culture could be joyful, relatable, and profitable.

It’s easy to see why House Party continues to resonate. Its colourful costumes and Hip-Hop soundtrack remain a vibrant time capsule. Yet, beneath the surface, it delivers an intimate portrayal of a generation that crosses racial boundaries. Hudlin’s thoughtful comedy widened the industry’s perception of urban communities, providing a window into a world where Black culture is celebrated without didacticism or caricature.

USA | 1990 | 100 MINUTES | 1:85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

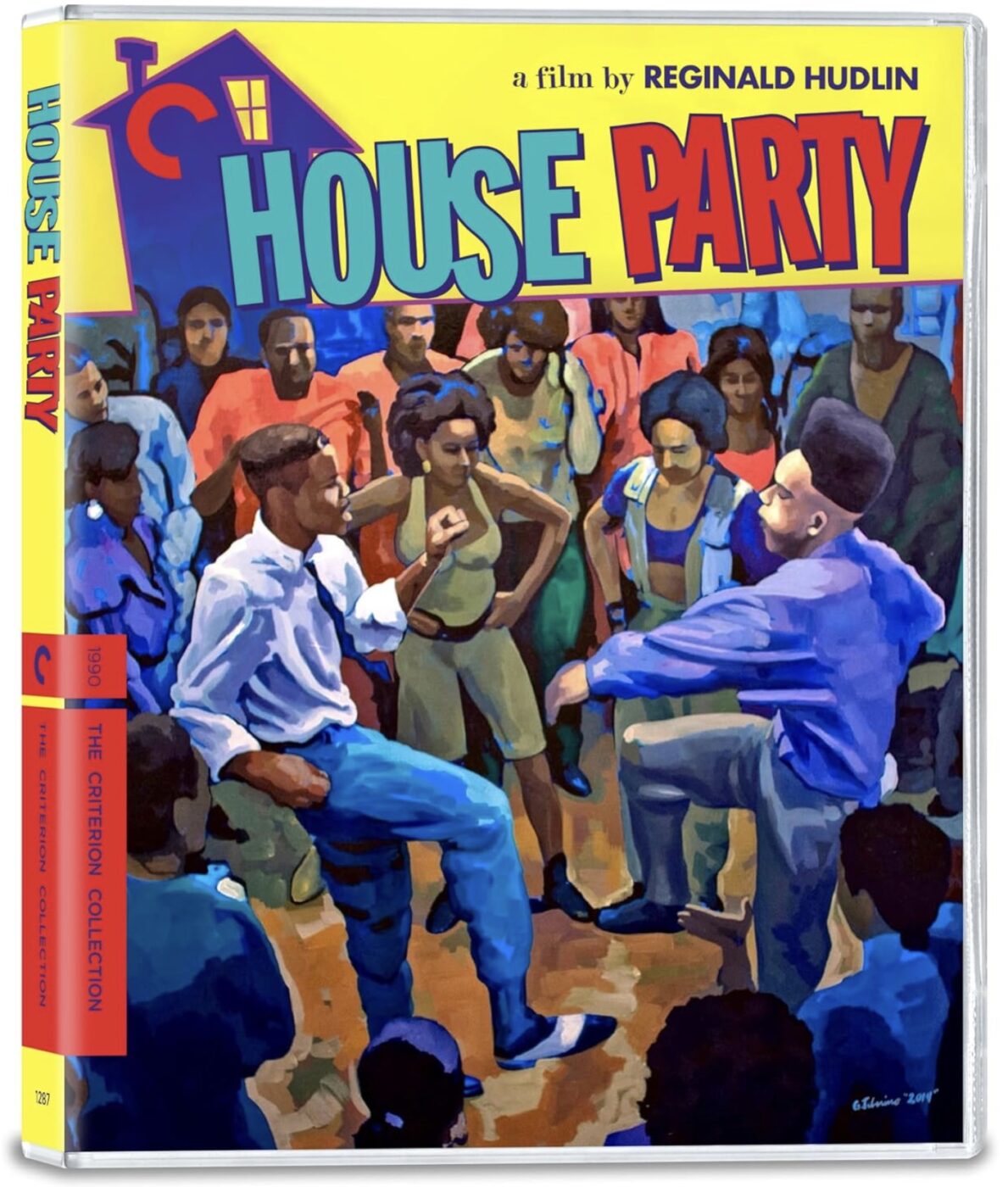

Showcasing a wonderful 2160p Ultra HD restoration, House Party has received an exceptional upgrade courtesy of the Criterion Collection. Sourced from the original 35mm camera negative and presented in its native 1.85:1 aspect ratio, the transfer was supervised by director of photography Peter Deming (Mulholland Drive) and approved by director Reginald Hudlin.

House Party has languished in home video purgatory for over two decades, with prior releases hamstrung by outdated masters. Criterion’s 4K UHD remaster rectifies these shortcomings, delivering a presentation that feels rejuvenated yet remains faithful to the film’s original visual character. The new transfer appears far more organic and possesses a beautiful photographic texture, showcasing a healthy amount of cleanly rendered grain. The addition of Dolby Vision adds a welcome richness to the saturated colour palette, providing a pleasing depth to the visuals. The vibrant primary tones of the notoriously flamboyant wardrobe appear striking yet commendably controlled. Reds remain rich without any traces of bleeding, while yellows are confidently amplified without appearing overblown. Similarly, nighttime sequences illuminated by blue hues are equally impressive, with contrast levels remaining stable and expertly managed.

The image contains wonderful depth, with a deceptive level of rendering that draws out striking delineation. Background details inside Play’s home remain crisply defined without ever appearing artificially sharpened or digitally processed. Tight compositions reveal a wealth of detail, showcasing everything from the intricate patterns of the characters’ clothing to the subtle beads of sweat forming on partygoers’ brows. Even softer imagery maintains consistent clarity—most notably the opening sequence in which Kid coats his hair with spray. Overall, Criterion’s new restoration of House Partyappears stunning from start to finish, remaining as flamboyant and exuberant as Hudlin intended.

This new release includes the original 4.0 surround soundtrack, presented as a single English DTS-HD 5.1 Master Audio track with optional English subtitles.

While the disc doesn’t receive a Dolby Atmos upgrade, the audio boasts excellent fidelity and dynamism. Dialogue is clearly prioritised at the front, allowing the surrounding channels to handle atmospheric sounds. The Hip-Hop soundtrack is perhaps the biggest beneficiary of this presentation; the instrumentals and vocals sound defined, reverberating across the soundstage with clarity. Admittedly, the track rarely erupts into a massive sonic spectacle, but this is certainly the most robust and polished House Party has ever sounded in a domestic setting.

writer & director: Reginald Hudlin.

starring: Christopher Reid, Christopher Martin, Martin Lawrence, Tisha Campbell, A. J. Johnson, Robin Harris, & John Witherspoon.