THE ICE STORM (1997)

In 1973 suburbia, several middle-class families experimenting with substance abuse and the swinging lifestyle find their lives spinning beyond their control.

In 1973 suburbia, several middle-class families experimenting with substance abuse and the swinging lifestyle find their lives spinning beyond their control.

One of the couples in Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm owns a waterbed. It sits unobtrusively in a modest bedroom, hugging the ground. It looks like any ordinary bed until the husband tiredly plops down on it. Little tidal waves are sent rippling under the surface, a tense ocean trapped under plastic, bobbing the wife up and down like a survivor on a rescue boat.

She, Janey Carver (Sigourney Weaver), remains facing away from her husband Jim Carver (Jamey Sheridan), her eyes fixed on her hardback Philip Roth novel. On the night-stand sits another book by John Updike. Jim is back from a business trip. He’s already checked in with his sons, who, after bearing witness to their father’s return, respond “you were gone?” They’re past the age of asking “did you bring us back anything?” The children need nothing from him, and neither does his wife.

The kitsch modernism of the time (The Ice Storm is set in upstate New York in 1973) may explain why the couple decides to trade in the tried-and-true marital bed for a glorified pool-toy. But the couple, a hallway and a galaxy away from their introverted teenaged sons, need to colour their lives with something. Hence these frivolous purchases, and a home like an adult playhouse: inflatable armchairs, waterbeds, conversation pits with shag carpeting and rabbit-eared TV sets that are always on. Outside, there are woods to play in, but they are inhospitable. The trees are bare and unclimbable. There’s a prevailing feeling of coldness and sharpness, as if you might prick yourself on the sharp air if not the brambles and branches.

There’s nowhere for the kids to go. Janey and Jim’s sons, Mikey (Elijah Wood) and Sandy (Adam Hann-Byrd) are on the borderline between childhood and adolescence, perhaps a year apart in age. Mikey is sharp and introspective, curious and filled with wonder about the world. Sandy still plays with Action Man dolls, though he’s recently begun blowing them up with fireworks on the back porch for fun. The sound of explosions cracking through the trees underscores just how quiet the place really is.

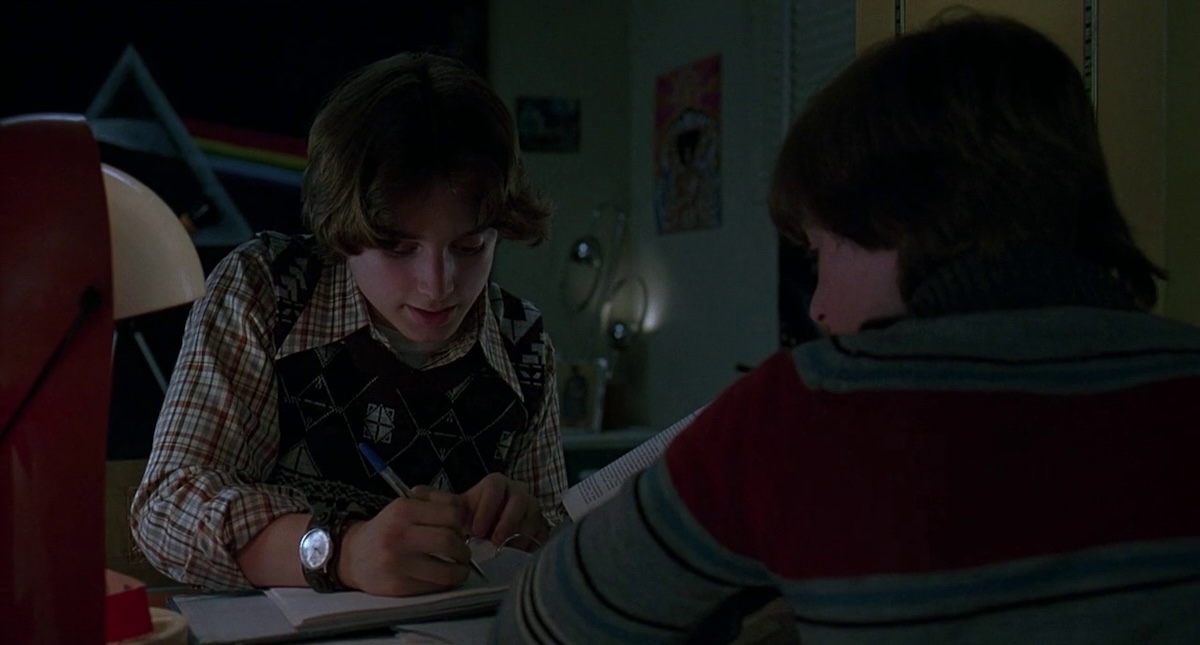

Mikey and Sandy talk in a constant low register, trying to neither be seen nor heard—by parents, by the environment. Sandy asks his big brother for help with his maths homework. Perhaps Mikey has been waiting to be asked a question—any question. He becomes thoughtful, his imagination running. “You can’t draw a perfect square in the material world”, Mikey tells his sibling. “But in your mind, you can have perfect space”. Sandy is appreciative, but it doesn’t help with his homework.

Another teenager, just down the road, is struggling to express and sort his feelings, too. Paul Hood (Tobey Maguire) is the smart, precocious 16-year-old son of Ben (Kevin Kline) and Elena Hood (Joan Allen). His parents don’t own a waterbed, but their actual bed is no more stable—Ben’s having an affair with Mikey and Sandy’s mother, Janey. Paul takes the train into the city by himself to visit friends; he attends an expensive boarding school, and dabbles in recreational drugs. He longs for pretty girls in his class and recommends Dostoyevsky novels to them. His voice is constantly cracking, the process of his voice breaking somehow still ongoing. He reads Fantastic Four comic–books, and ruminates on the nature of family via internal monologue.

“Your family is your own personal anti-matter”, he muses. “Your family is the void you emerge from, and the place you return to when you die. And that’s the paradox: the closer you’re drawn back in, the deeper into the void you go”. Here, the literary origins of The Ice Storm present themselves—the film was adapted from Rick Moody’s 1994 novel, and the teenagers speak as if they’re hoping to be quoted.

But Rick Moody, Ang Lee and James Schamus, who helmed the screenplay, cut to something more pertinent and truthful here; kids, teenagers, do perform, they espouse, and they write poems, songs and make declarations – particularly when they are not being listened to, and their frustrations require an outlet. Paul and his 14-year-old sister, Wendy (Christina Ricci), are wise enough to recognise that things at home aren’t going well.

Yet The Ice Storm is restrained, repressed—for all of Paul’s treatises on the world, for all of Wendy’s political calls to action (“Wendy, would you cool it with the political assassination talk?” sighs Ben as his daughter watches Nixon on the nightly news after dinner), nobody talks about anything that is actually happening under their own roofs. Elena floats through the home as if in a constant state of shock, or perhaps loss.

We watch Ben cover his tracks, offering up half-hearted explanations for his visits to the neighbours’ house. We sense that Elena already knows. Perhaps Ben knows this, too, and perhaps the stultification that one experiences in adult life is miserable enough to secretly long for an explosion. It never really comes; feelings are delayed and denied, affairs are unsatisfying—the atmosphere is too frozen to ever allow for combustion.

Ang Lee and his cinematographer Frederick Elmes present environments and characters that should belong in a Douglas Sirk film: lavish yet claustrophobic home interiors, secret longings and disappointments that freeze in the winter. Sirk’s films could swell and pour forth with feeling; here everyone is too damaged to express much of anything. Ben and Janey’s affair isn’t one of fireworks – she lies staring at the ceiling during and afterwards, Kline stealing glances to try to extract information. Is she enjoying this? Am I? Is anyone?

The Ice Storm’s wry humour comes from exactly this emotional constipation—Ben is unable to offer up even a cursory “was it good for you?” after the fact. When secrets do start coming out, it’s often with resigned acceptance rather than histrionics. When the shouting does come, Wendy can just turn up the volume on the TV set—it has probably taught her more about human behaviour than her parents ever could.

And the children watch a lot of television. They watch the news, where Watergate is playing out like it’s the movie of the week, the prevailing mood one of deception and sneaking around in the dark. They watch the proto-reality series, Divorce Court, and the sitcom M*A*S*H (1972-1983). War, marital strife, treason—is this the world the children are so eager to join?

They are the definition of latchkey kids, coming home to empty houses, babysitting themselves while their parents attend key parties or conduct affairs. The sexual revolution of the 1960s has been and gone—these are people who are still trying to get blood from that stone, or else missed it entirely the first time around.

Kids and adults alike fool around with each other in locked bathrooms and basements. In one scene, Wendy picks up a Richard Nixon mask and pulls it over her head. She and Mikey are alone, and they start to fool around. Mikey is nervous, while Wendy finds a degree of remove from behind the rubber mask. It’s a disconcerting tableau, and a hopeless one too.

Kids are curious about themselves and about each other, but in The Ice Storm, it only leads to more confusion, more distance. They are children playing pretend, dressing up in Halloween masks that depict disgraced leaders, in turn attempting to lead each other through the mess they’ve been dropped into. Ben walks in on the scene, chastises the kids and retrieves his daughter. He must be careful to avoid the fact that he too was in the Carver family home at that time to continue his affair with Janey. Another stalemate. What are these children supposed to do but recreate whatever it is they see their parents, their leaders, doing? What else is there but deception and the thrust for self-pleasure?

As Ben walks his daughter away from the Carver home, back through the barren elms of Westchester, she tramples through a puddle. It’s an act of teenaged defiance, a way to suggest to dad that she doesn’t care for the clothes he’s bought her, nor for her own wellbeing. But it only makes her seem like a kid. They walk quietly, the forest creaking. Ben asks if her feet are cold. She has before her two options: independence and defeat. She nods. Ben picks her up, her legs wrapped around him, head rested on his shoulder. He carries her out of the trees and back towards the car. It’s a stunning moment.

Ang Lee’s film does not scold, nor judge. His characters are flawed, not malicious, naive rather than cruel. It’s permanent midnight in America: are your kids at home? Are your parents?

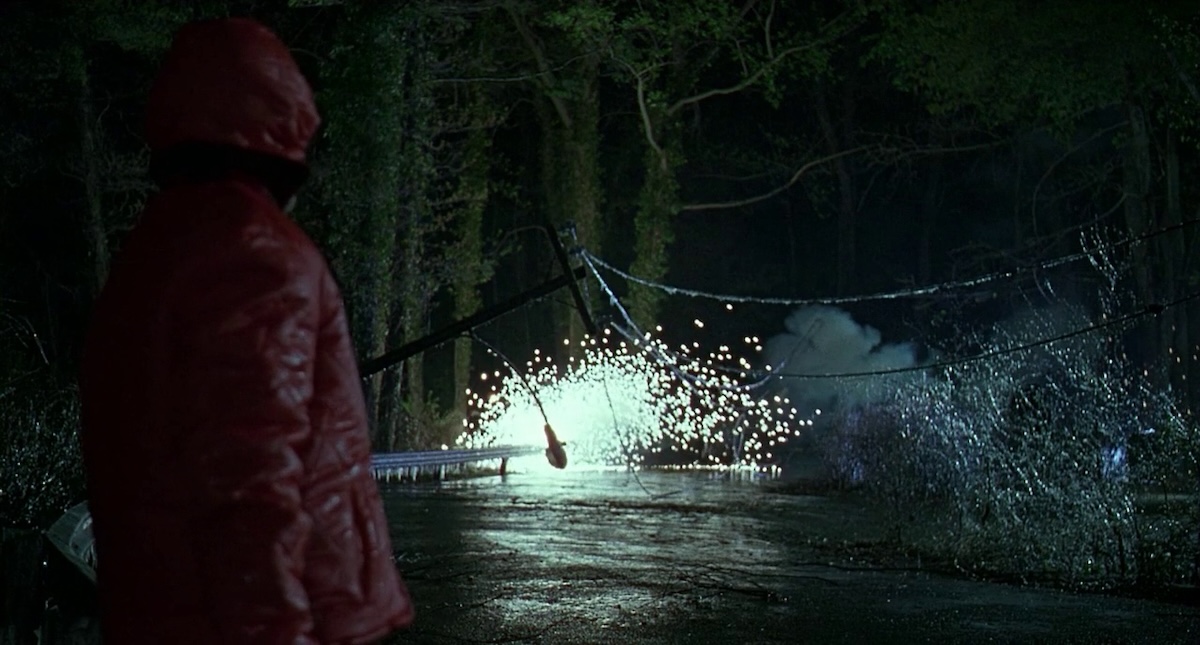

Lee’s most stirring moments spring from quietude and stillness. The grace with which the Samurais glide through the trees in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), the cold wind that howls through the Wyoming Mountains in Brokeback Mountain (2005), the frozen train car that slowly ticks and crackles to life, warming slowly with an electric pulse in The Ice Storm; each demonstrate a director with a thoroughly non-Western sense of patience, of watchfulness and solitude.

Lee does not rush the viewer along—we’re not harangued with an American sense of overstating things. In this sense, Lee’s style is perfectly suited for a film taken from a novel—he relishes not just in the dialogue, but in what’s unsaid, what remains and lingers in the elements. The Ice Storm is less about two families, and more about the brew of it all; the families and their interactions, their homes and their achievements, their jobs and salaries; whom they vote for or do not vote for; whether they sit at the dinner table to eat together or hide out in satellite bedrooms, away from the mother planet of the family living room.

Ang Lee’s focus on the elements, on texture, and on places, enriches The Ice Storm’s novelistic beginnings, filling out a world so cluttered with human stuff: we wander down the aisles of chemists’ and sit in cramped cars as freezing rain batters the roof. We listen to the pipes and tambourines that howl ancient and ghostlike through the woodlands. Thanksgiving dinners are prepared, and a prayer is spoken by Wendy that concludes with her quipping “Thank you to all the white people” who “killed all the Indians and stole their tribal lands”.

What was the American family, in 1973? It was just a few years before the country’s bicentennial, and here is a fledgling nation with no sense of how to rebuild what it’s already destroyed. Here is the nuclear family that can only exist in this place, in this time, because of destruction and death. Sitting down to a calorific meal, a bottle or two of wine, and maybe a sitcom or football game afterwards, nobody here seems to quite know what they are doing, or why they are doing it. Is there some spirit stirred from the land, bound to ever haunt them with dissatisfaction?

An ice storm is coming, and it’s going to be one of the worst storms of the century. But it will play out in the background. Ben and Elena won’t put chains on their tyres. Janey and Jim won’t stock up on household necessities. Nobody will come together until the damage is already done. Water will freeze in gutters and congeal into ice, but Jim and Janey’s waterbed will never freeze, will never be still.

Each infinitesimal movement will push the other further away in seasick arcs. The lifeboats are gone, and a continual sense of disappearing under the waves of a dreadful storm will take hold—but perhaps this is still preferable than looking somebody in the eyes and telling the truth.

USA • FRANCE | 1997 | 113 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

This Blu-ray release of the film in HD 1080p is a welcome improvement over the older DVD editions of the film, but it isn’t a startling transfer. The Ice Storm is a beautiful film, filled with gorgeous textures—the close-up of the pages of a comic book, ice in a tray at cocktail hour—and while this is a pretty good representation of the film, a new re-master, or even a 4K Ultra HD upgrade, would’ve been ideal.

As it is, the leap between DVD and Blu-ray isn’t gigantic. The film’s cold colour palette is represented naturalistically, and there’s true richness to the interior scenes; it all just looks a tiny bit flatter and less dynamic on disc than you’d hope for when it comes to a film this beautiful to behold.

The soundtrack was clear, with dialogue sounding crisp and the film’s soundtrack particularly standing out. It isn’t the fullest mix I’ve heard, and it tends to linger on the higher end of things, but it does the job.

director: Ang Lee.

writer: James Schamus (based on the novel by Rick Moody).

starring: Kevin Kline, Joan Allen, Henry Czerny, Adam Hann-Byrd, Tobey Maguire, Christina Ricci, Jamey Sheridan, Elijah Wood & Sigourney Weaver.