GHOST IN THE SHELL (1995)

A cyborg policewoman and her partner hunt a mysterious and powerful hacker called the Puppet Master.

A cyborg policewoman and her partner hunt a mysterious and powerful hacker called the Puppet Master.

I’m filled with awe every time I watch Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell. Its rich chroma, muted by the bloom of the sun, its visually advanced world that’s set in the near future yet still contains elements that emulate urbanisation of the now, its musings on existence and ownership of thought—all of it. It’s undeniably the most profound piece of filmmaking I’ve ever seen.

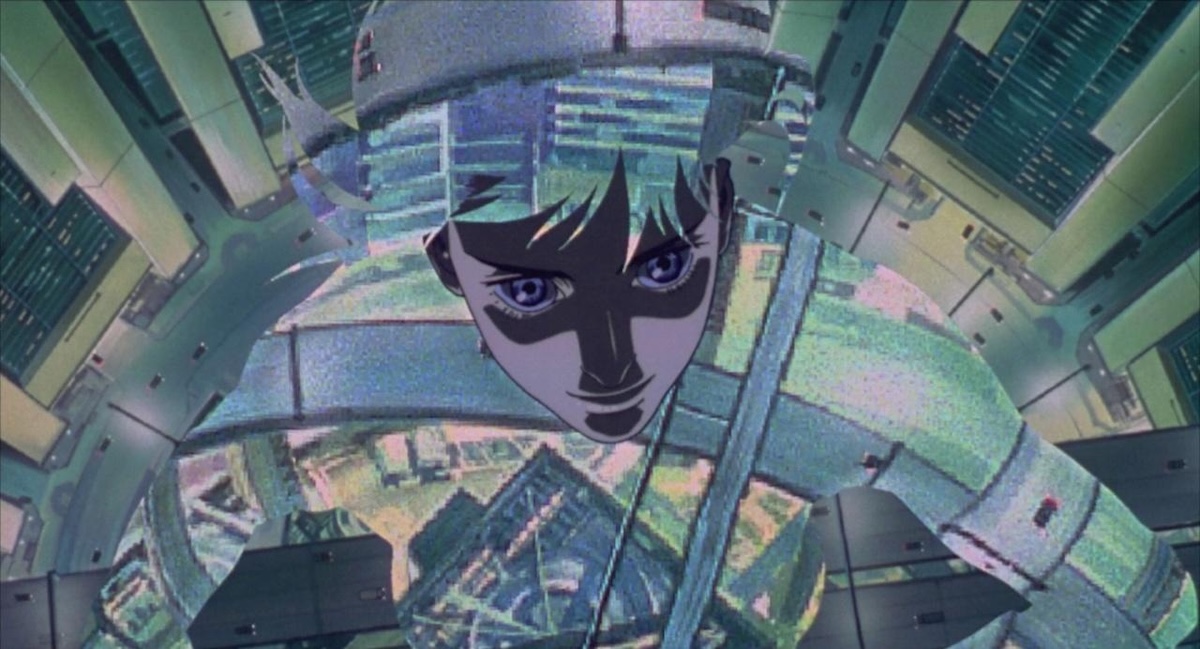

The skyscrapers of New Port City, Japan, do more than touch the sky; they push the boundaries of architecture and technology. I can envisage myself standing within its interwoven grids of asphalt, looking upwards to mechanised beauty and overwhelmed by all that stands before me. Its buildings, monolithic in nature, are accented by the combination of minimalist and futurist architecture and small, warm orange and red lights to guide pilots in the nocturne.

They’re sleek, made of polished metallics of a singular colour so as to give a uniform look to the entire city. The best way I can describe how I feel when viewing this microcosm is that I’m hit with ‘metrovertigo’, though the term’s not my own. You can thank a certain third-wave, avant-garde blackened death metal jazz trio for that one.

My gaze, now pivoted towards the ground, looks more familiar but overwhelming still. Buildings here are weathered with streaks of rust dripping down alongside their exterior; neon incandescence extends like branches from the sides of buildings, while industrialised wiring connects these separate neglected structures together, creating its own uniform look, but of a much lesser lustre; and the general filth from the wake of mankind can be seen, stretched across every inch of the city’s roots, like vermin endlessly populating.

I’m stunned at how detailed these background paintings are. Gouache goes a long way, but the added layer of transparent film with acrylic-painted structures helps create a sense of depth and volume to make this city feel naturalistic, like a living, tangible thing. I can scrape the rust off buildings in the slums. I can feel their weathered shingles, the concrete walkways, and the accumulated filth left by the self-centred and uncaring. The layering that is possible with this painting medium is endless: how thick and bold or thin and soft they can appear and the varying degrees of control with colours. The best part is that all you need is a little water. Unbelievable.

It’s clear as day that the design of this city is inspired by Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982). There’s no denying this, nor do I need a statement on record to prove this as fact. Outside of architectural and automotive advancements, technologies and the sciences have gotten to the point where cybernetics fully replicate the anatomy and the many systems of the human body and can fully quantify the brain. Remarkable as it may be, all of its world’s advancements are matched by its day-to-day sufferings. The laborious grind, the stifling and oppressive design, the lack of autonomy of some, and the desperation of others—it’s all there, and within it, like our world, we question so much.

Oshii’s philosophical musings on existence and meaning from his past works, including the ones in his cancelled Lupin the Third film, are present here, yet something is different; something makes it click, makes it feel more complete. He strived for a sense of wholeness with his first original film, Angel’s Egg (1985), but was missing a crucial element for it to have any staying power.

What he was lacking was the relatability and familiarity found in the Andrei Tarkovsky films he was inspired by, where their characters go through the same contemplative struggles we go through, specifically that of faith and the philosophical, which is then bled into the film’s environments, shaping them to match the mood of its characters. Thankfully, Oshii learned his lesson. Visual abstraction no longer exists, nor do long and static shots. In their place is time spent on world-building through visual proficiency, complementary and dynamic cinematography, and a focus on the human condition.

In times of hardship, no matter how relentless, we meditate on the nature of our existence. We ask many questions. Why do we suffer? What’s the point? What’s my purpose? Is there meaning to life? Is any of this real? Am I real? What makes me so? These reveries stretch as far back as civilisation itself, and yet an answer has never been solidified, only debated.

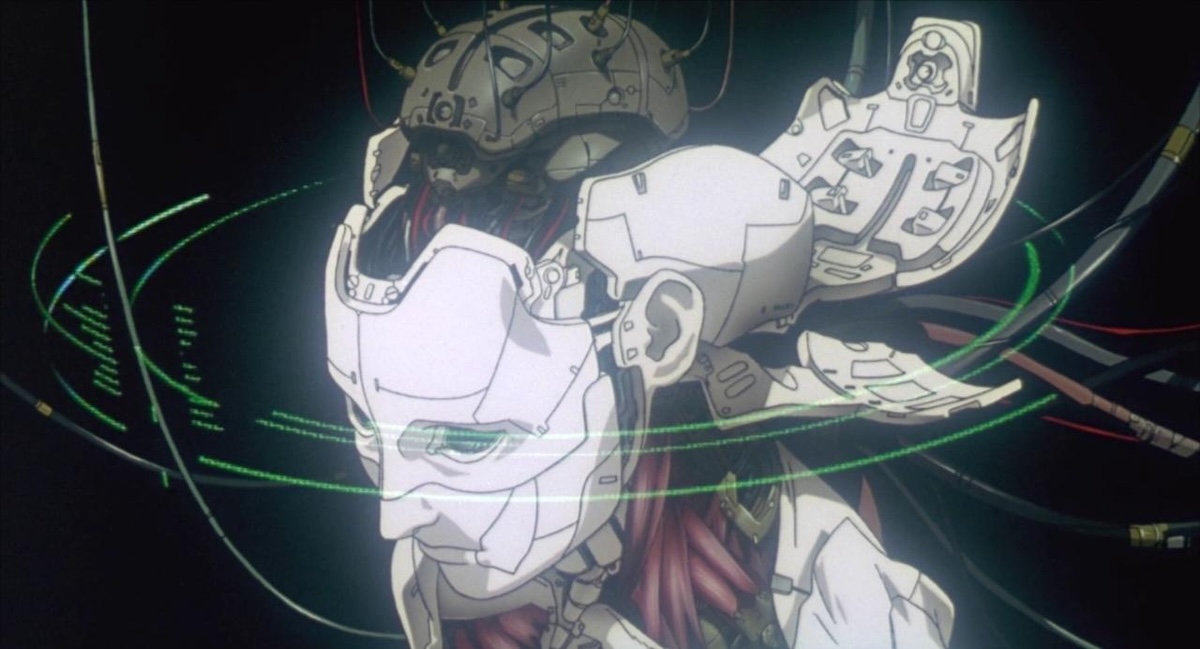

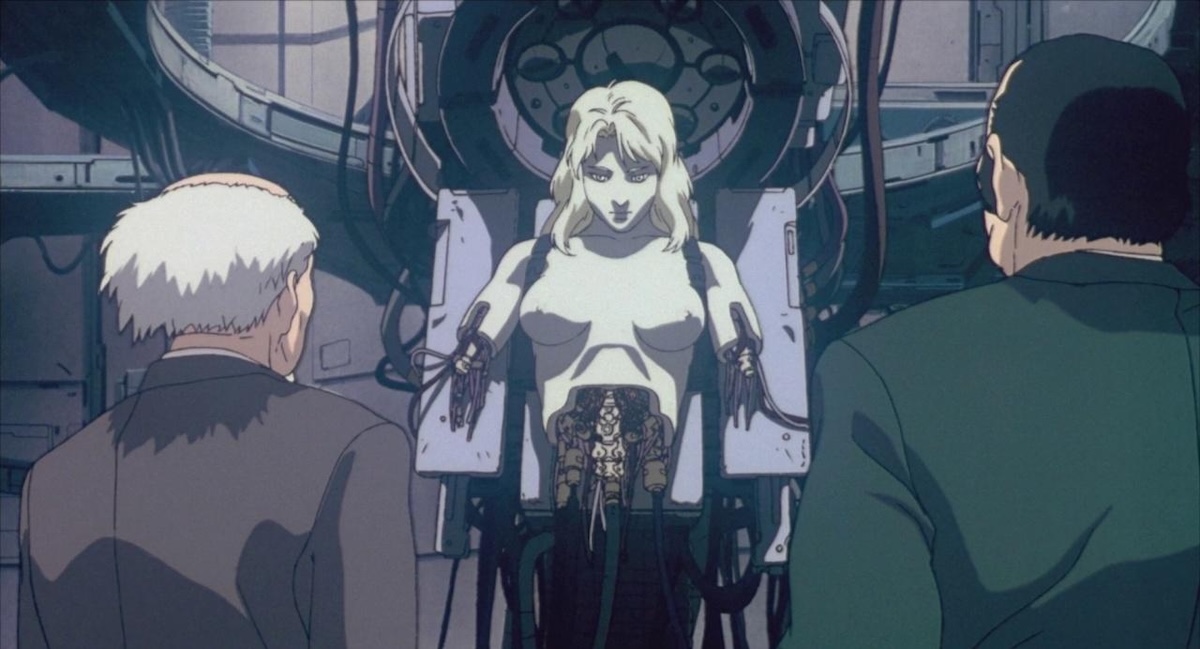

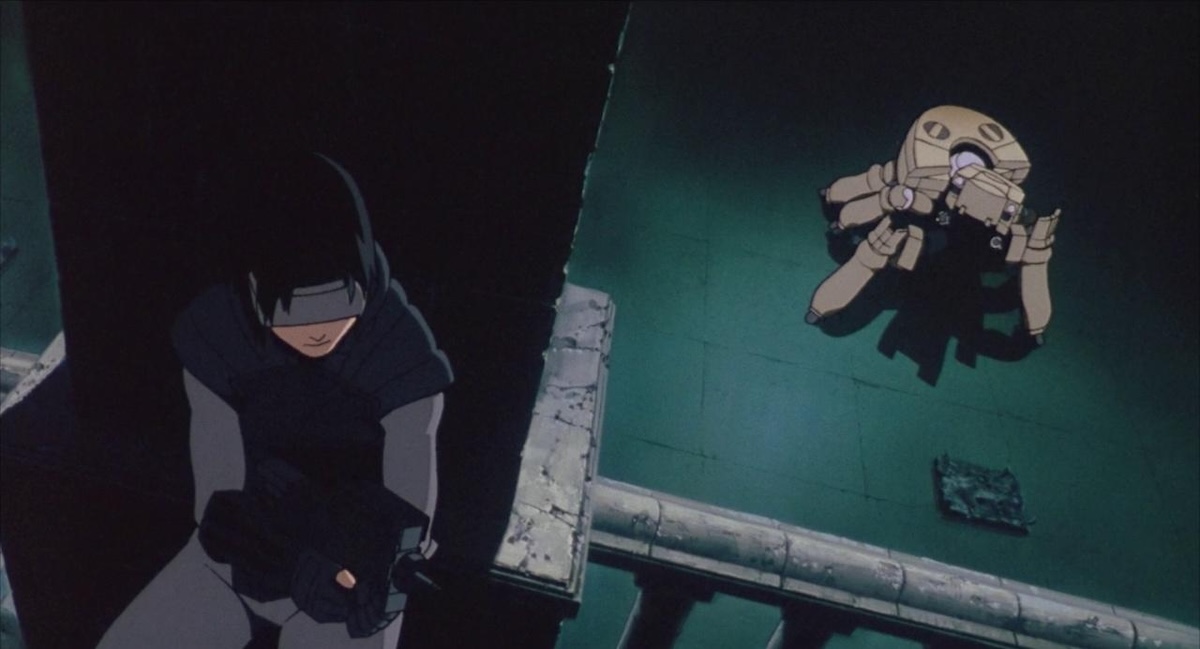

I see these same questions asked by Motoko Kusanagi (Atsuko Tanaka) during Section 9’s investigation of the Puppetmaster (Iemasa Kayumi). Motoko, outside of her brain, is fully cybernetic, yet her brain is augmented to a titanium casing that allows it to interact with the technological facets and intricacies of its world. She doesn’t remember her past; her memory only contains her time working under Section 9. They’re responsible for her design, as well as her fellow officer Batou (Akio Otsuka) and other members of this law enforcement division.

According to Batou, they can leave Section 9 at any time, but Motoko reminds him that if they do, then they would have to return whatever was given to them: their cybernetics, their augmented brain, and everything stored in it, including their memories. This fact, plus the politically motivated, brain-hacking occurrences of the Puppetmaster, is what brought Motoko to this place of contemplative fog. While spending time with fellow officer Batou on his boat after diving in the bay, Motoko takes a drink and questions the significance of the “I” if it can be taken away from someone. Memories, emotions, and thoughts may not necessarily define an individual.

What I love about this scene is how these musings questioning the famous Cartesian maxim are played after a beautiful set piece of animation, where Motoko dives deep into the bay, forcing herself to linger in the darkness before rising to the surface. The waters are a deep black, similar to the black used by Yoshitaka Amano’s choice in Angel’s Egg, yet appear hazy to give a distinction of being in a body of water. Through the darkness, the orange sky pierces through the surface of the bay, which is now visible as Motoko ascends to the surface, yet as she draws closer, the water shifts from black to teal, then gives way to a deep blue before it shifts to the orange sky.

Art director Hiromasa Ogura blends the colours of the water together, but not entirely, so as to keep their presence somewhat separated to illustrate the layers of the ocean’s depth. He chooses to omit blending the sky and the top layer of water altogether, seeing as they are complementary colours and blending them would cancel each other out, creating a muddy neutral colour. Instead, he layers them on top of each other, making it unclear which is the bottom layer and which is the top. There’s a layer of white that’s washed on top of this convergence line, obscuring it yet softening it visually, as it seamlessly blends into the orange and blue. This beautifully animated scene exists as a visualisation of that very same internal plunge Motoko takes and shares with Batou in the following scene.

The actions of the Puppetmaster (Iemasa Kayumi) warrant Motoko to continue these ruminations. Batou at one point asserts Cartesian influence to ask if the notion of the self isn’t enough for her, while at another point, we see Motoko gaze at various people and inanimate objects imitating the human form only for her to see herself in their place.

The Puppetmaster’s meddling in political affairs involves hacking into cybernetically enhanced human brains through a link to what is called a “ghost”—what is implied to be the soul—to carry out their plans, all the while highlighting the consequences that come with man’s accelerated progress. When finished, the person’s memory, their sense of self, and their identity are all wiped clean. They leave no traces of themselves, just a sterilised tool at the crime scene.

This “pulling of the strings” is what got this international cyber terrorist hacker their name, yet it also stands to reason that their actions are of the same philosophical and psychological contention/alternatives towards the notion of the self and ownership of thought. Ideas and emotions simply just come to us. Nobody thinks about getting mad when something happens that is unfavourable, like dropping food on the floor or losing to an opponent in a high-execution fighting game because the net play is dogshit. They just come to us. It’s the same with inspiration.

Whatever form of contention or alternate ways of thinking exist, they all bring Descartes’ principle to the point of obsolescence. As I see it, it’s no longer “I think, therefore I am”; rather, something is thinking, and we’re just receptive to it.

The thought of just being while something else influences and guides us is horrific. Even the most fearless of people quiver and piss. Look no further than the garbage man in this film; he’s used as a tool by the Puppetmaster, then wiped clean. When questioned, the man is dripping sweat and frozen stiff with the profound realisation that everything they thought they knew—their memories, their life, their existence—was all a fabrication. We witness these reflections of losing one’s sense of self earlier on Batou’s boat through discourse, and now we see it occur to a random blue-collar civilian.

This scene hits me every time. The soft bloom of the sterile lights used in the interrogation room, reflective of the garbage man’s current state of being; his eyes wide open, staring downwards into the photo of what he once perceived as his wife and kid that he has held firmly in his hands; the colour of the bandage on his chin closely matching the colour of his eyes so as to balance all the degrees of teal used as the cool of the shot amidst the off-whites of the back of the photo and his skin; and the tears that fall down his face.

This is that clicking point I mentioned earlier, that moment where our plights align with the fictional world, the creation of relatability and familiarity that absorbs the viewer into the film. This is what was missing from Angel’s Egg. This is what is missing from a lot of films that attempt to craft a microcosm, now that I think about it.

What I find impressive about this point of the film is that I feel it’s easier to craft a successful microcosm when real people and real settings are used, yet Oshii does this through animation. He fuses real-world miseries and meditations with the progress of this fictional world, bridging the gap, so to speak, and with this fusion comes a nice little perk: the impact of its plights and ponderings is made more horrific with its world’s technological advancements.

The fact that the mind, now fully quantifiable, mechanisms and all, can be replicated, manipulated, and erased warrants further questioning, no? Ghost in the Shell not only shows the philosophically profound, but it also warrants participation. If this is all possible, what does that say regarding one’s ghost, or in our case, the soul? Does it even exist? Maybe it doesn’t. Maybe we are just an extension of whatever force influences us. Maybe there is no ghost in the shell.

With Oshii’s direction and the combined talent of Ogura’s art direction, the dynamic and well-composed cinematography of Hisao Shirai, the screenplay by writer Kazunori Ito, and the culturally Eastern-sounding ambient score composed by Kenji Kawai, Masamune Shirow’s manga series of the same name is brought to life, which I’ve yet to read, but I have read that the film is a rather faithful and interesting adaptation.

Apparently, it’s the story of the first volume of the manga, but Ito selected bits of its dialogue and specific visually striking occurrences from different scenes of several unrelated moments in the other two volumes of the manga and blended them together to accent and uplift this story arc. I need to make it a point to get my hands on them soon. Ghost in the ShelI is one of my favourite films ever made, so not having read the manga feels like a sin.

If there is one thing I really enjoy about this film, it’s that there is an answer as to the “why” of our existence, which, when combined with its philosophical meat, is what makes this film one of the most profound pieces of filmmaking I’ve ever seen. This answer to the “why” is what the screenplay is written around, making its philosophical musings actual musings rather than a mere dressing. I’ve seen this “why” done in other animated media I’ve seen—the series Serial Experiments Lain (1998) comes to mind—yet I’d argue that they don’t execute it nearly as well as it’s done here.

In my eyes, Ghost in the Shell is a perfect film: a true piece of cinema. Oshii not only learns from his past mistakes but also creates a film that I’d argue is on par with the contemplative work of Tarkovsky, Yasujirō Ozu, Béla Tarr, and Theodoros Angelopoulos, and he does so in half the time and at such a brisk yet fruitful pace. In fact, I prefer Ghost in the Shell over the rest of these filmmakers’ work, with the exception of Tarr. You’d think these art-minded fans of cinema would have recognised this film’s quality by now. It deserves a spot on Sights & Sounds’ ‘The Greatest Films of All Time’ list—to be honest, I’m surprised it’s not on there already. Maybe people will wake up one day.

JAPAN • UK | 1995 | 83 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Mamoru Oshii.

writer: Kazunori Itō (based on the manga by Masamune Shirow).

voices: Atsuko Tanaka, Maaya Sakamoto, Akio Otsuka, Iemasa Kayumi, Yoshisko Sakakibara, Koichi Yamadera, Tamio Ōki, Yutaka Nakanom Tesshō Genda & Mitsuru Miyamoto. (Japanese) • Mimi Woods, Richard Epcar, Tom Wyner, Christopher Joyce, William Frederick Knight, Michael Sorich, Simon Prescott & Richard Cansino. (English)