NEVER LET ME GO (2010)

The lives of three friends, from their early school days into young adulthood, when the reality of the world they live in comes knocking.

The lives of three friends, from their early school days into young adulthood, when the reality of the world they live in comes knocking.

One of the most obvious questions that springs up in relation to Mark Romanek’s Never Let Me Go (adapted from the highly acclaimed novel of the same name by Kazuo Ishiguro) is why its trio of main characters never think of running away from their horrific circumstances. They are groomed into pursuing incredibly short lives as organ donors, having been raised to be submissive and subservient to the whims of their society’s abhorrent rules. In childhood they’re shepherded around and threatened with horror stories about leaving the countryside mansion where they are tutored alongside other youngsters in the same predicament. This, it becomes clear, is the sunny part of their lives, where a sheltered environment can only go so far in dimming the whims, dreams, and wonder of children, just as it can’t always shield them from the horrors endemic to this society.

In fact, the movie’s opening scenes are practically cheery, exploring the shifting dynamics between the three children at the heart of this story— Kathy (Isobel Meikle-Smith and Carey Mulligan), Ruth (Ella Purnell and Keira Knightley), and Tommy (Charlie Rowe and Andrew Garfield)—instead of wading through the scientific jargon or ethical considerations underpinning this fictional society. The same strain of politeness and charm masking a brutally subservient and self-punishing mentality can be found in another adaptation of Ishiguro’s works, The Remains of the Day (1993), another tragedy which aims its savage critique at how institutions and social standings can produce limp people who accept less than they deserve. Both films’ protagonists are calm under intense duress, heartbreak, or impending doom, making one wish that their hearts would stir more violently at the stasis that has gripped them their entire lives. This banal, pleasant surface mirrors the outward sense of calm projected by both films’ grand country manors.

A simple childhood tale, well-told but with little ability to capture the authentic ebbs and flows of childhood (the child actors are talented, but even their impressive ability to communicate emotions silently doesn’t dampen the fact that they seem like theatre kids instead of real children), soon devolves into something far more horrific. One of their teachers, Miss Lucy (Sally Hawkins), lets slip their predicament and the reason for their existence. When they reach adulthood, they will be subject to surgeries for organ donation. Most make it to their third surgery before perishing; no one has ever survived a fourth. Hawkins is blessed with the ability to not just look radiant when she smiles, but to appear so kindly and self-assured that you can’t help but be swayed by her words. She has a very small role here, but it’s also one that perfectly emphasises her talents.

What impresses most about these childhood scenes is how easily they move the story along without ever losing track of these characters’ emotions. There are no awkward or clunky expositional passages; Carey Mulligan’s (Far From the Madding Crowd) voice-over narration bookending the film isn’t just tasteful, it is essential to the emotional experience. Following these characters across three distinct points in time in their lives only makes the terrifying and beautiful aspects of the film more poignant.

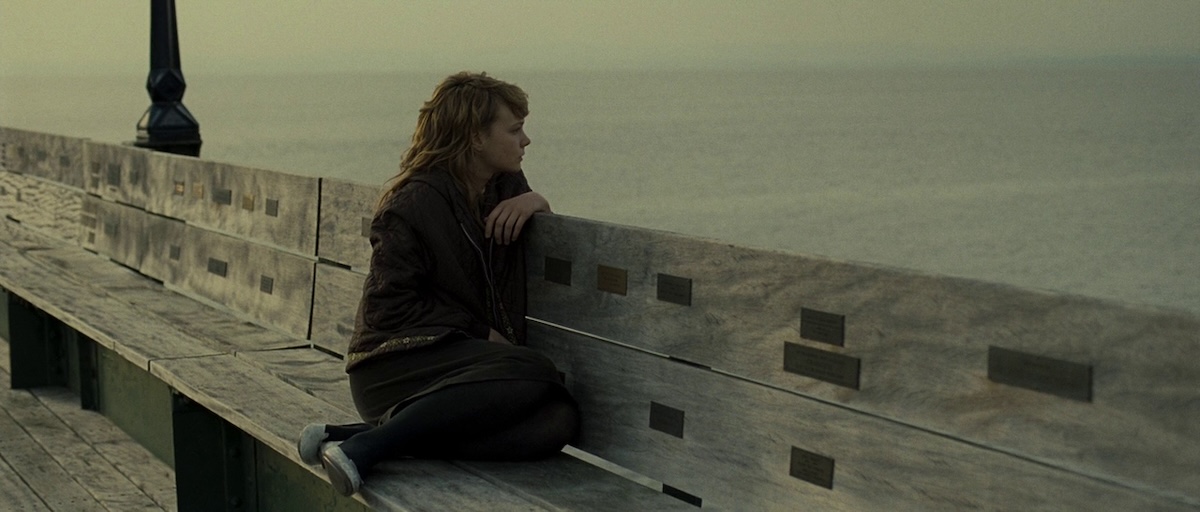

Romanek’s direction is also wonderfully understated, subtly drawing out the false veneer of pleasantness in this story, the horror endemic to it, and the changing tides of childhood, adolescence, and adulthood. But most impressive is how these characters somehow feel like autonomous beings even as they’re shackled to an ideology that has permanently severed their ability to imagine a world in which they rebel against its social order. These characters are adamant to work within the system that they were thrown into, yet don’t spend their time reciting the dogma of their tutelage. They aren’t fanatics, or even politically active. You get the sense that they hardly ever interact with ‘regular’ people. All they have is a belief that their lot in life has already been decided. Never Let Me Go works as both a terrifying alternate reality in the vein of science fiction storytelling from the likes of Raymond Bradbury, and a film whose implications on remaining placid and agreeable retain their relevancy.

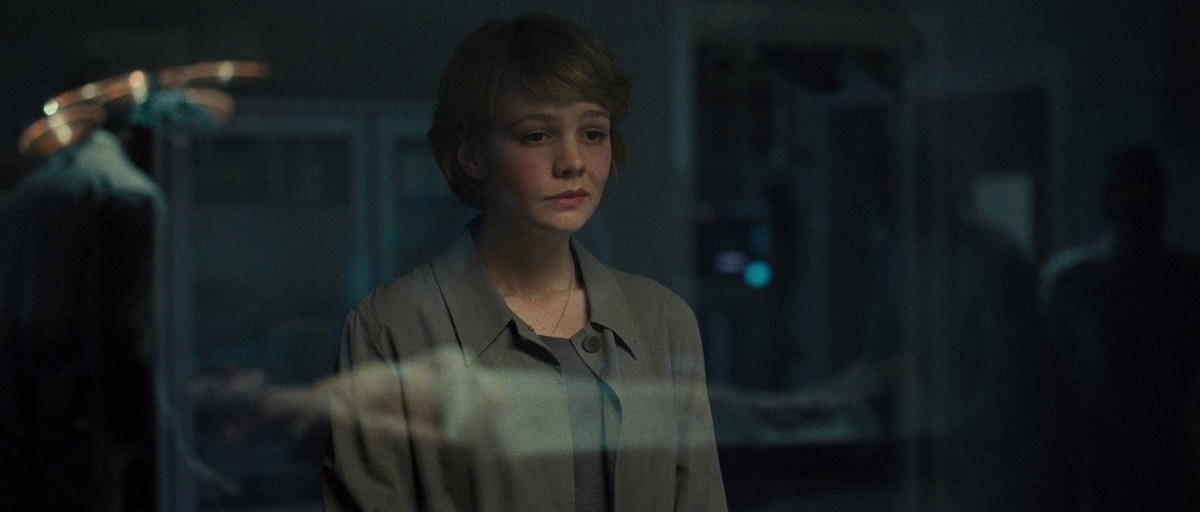

But despite all of its many strengths, I was left with one burning question while watching Never Let Me Go: why isn’t this more devastating? The screenwriting is a fantastic exercise in distilling time jumps, lofty themes, alternate history, and romantic drama into a compact script. Carey Mulligan is phenomenal, bearing a similar warmth that Hawkins conveys so effortlessly, but an even softer, sadder form of it. She is the ideal actress to play a woman not strong enough to defy the cruelty of her life’s path, yet who approaches this inevitability with poise, warmth, and even appreciation for what little time on this Earth she’s been allotted. Ruth is also an appreciably annoying character to contrast Kathy’s behaviour, whether that’s down to her teasing of Tommy in childhood or her scheming as a teenager. The sci-fi elements complement the film’s love triangle, and vice versa.

If this were a checklist, Never Let Me Go would have ticked all the boxes for garnering a strong emotional reaction (even the minor ones, like finding child actors and actresses that aren’t just talented, but who bear a solid resemblance to their teenage and adult counterparts). But a movie is not a checklist of all the things it does right or wrong, and part of what makes this film a frustrating watch is that its faults can be found in all the things it doesn’t say. There’s an unsettling quality to Never Let Me Go’s childhood scenes, but not much room for analysis on the kids’ part as to what their teachers think of them. They don’t have to necessarily fear their educators, but some level of internal conflict would go a long way towards articulating the oddity that is their existence.

Never Let Me Go is a very careful and precise film, using its modest budget wisely by employing few locations. As I was watching it, I thought this was an excellent move, with brutalist architecture present that both highlights and blends in perfectly with this alternate history of England. But there’s still something missing, and that’s a voice. There’s no guiding voice in this story to pick at its characters’ contradictions and their general lack of curiosity. This absence makes it hard to believe that someone as cunning or ruthless as Ruth wouldn’t make an effort to change her fate and fit into everyday society. She’s an avid conversationalist with a talent for twisting people and interactions to map onto her version of reality. But the film can never tackle these thorny issues of identity, lacking a clear way of burrowing deeper into these characters’ states of mind.

The character development might be tightly plotted and generally well-made, but it’s all too neat and tidy to capture fleeting joy or profound sorrow. Thankfully, Ishiguro’s novel covers that ground wonderfully through Kathy’s first-person writing, exploring a conflicted young woman who keeps flitting back and forth between memories as she attempts to make some sense of her life. Obviously, there are aspects of her existence that will never be clear to readers, but Ishiguro manages to cleverly highlight this while also emphasising that we aren’t too dissimilar in our scattershot approach to memory and what the sum total of our lives truly means.

Kathy is constantly ruminating, lending generosity to Ruth’s selfish acts time and time again, letting us know that all of these reflections are filtered through the wisdom and clarity that time has provided her. She sees these memories in a new light even as she’s in the middle of reliving them. Kathy is an ordinary woman who was once an ordinary teen and an ordinary girl, wistfully looking back on a time that seems so simple to her and so profoundly strange to readers (mostly because she conveys her circumstances in such an offhand manner, as though we should know all of this information already). There is so much clarity in the way that Ishiguro conveys her gentle kindness, her understandable moments of irritability and conflict, and the ways in which she can’t even understand that her life is a tragedy. There is beauty in that idea somewhere amidst its pain, which this film adaptation, lacking a strong internal voice and the slew of contradictions inherent to it, cannot access.

UK • USA | 2010 | 103 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Mark Romanek.

writer: Alex Garland (based on the novel by Kazuo Ishiguro).

starring: Carey Mulligan, Andrew Garfield, Keira Knightley, Charlotte Rampling, Nathalie Richard, Isobel Meikle-Small, Ella Purnell, Charlie Rowe, Sally Hawkins, Domhnall Gleeson & Andrea Riseborough.