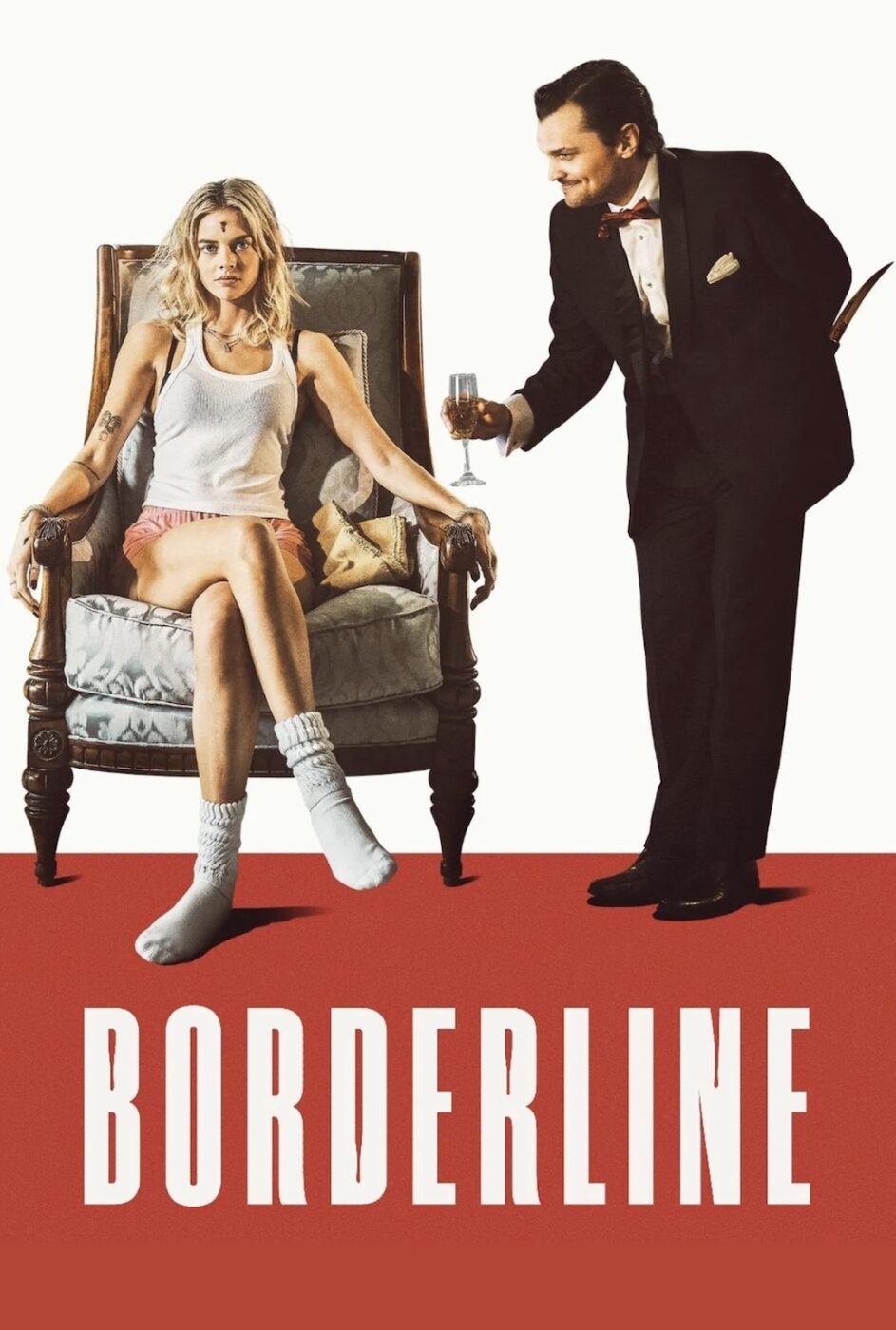

BORDERLINE (2025)

A bodyguard protects a pop superstar and her athlete boyfriend from a determined stalker in 1990s Los Angeles.

A bodyguard protects a pop superstar and her athlete boyfriend from a determined stalker in 1990s Los Angeles.

Pop stardom and fandom are the targets in Borderline, a psychological comedy thriller from first-time director Jimmy Warden, whose previous credits as a screenwriter include slasher sequel Babysitter: Killer Queen (2020) and the creature feature comedy Cocaine Bear (2023). Each film’s titls hint that Warden’s aware on which side his bread is buttered; these are cheap and cheerful B-pictures with no delusions of grandeur. That his next film, named simply Naughty, promises a bright future for this mode.

However, for all the irreverence and mischief at play in Borderline, Warden struggles to settle on what the film actually is, and what and who it’s actually about. It can make for a watch that is partly fascinating, partly frustrating.

Paul Duerson (Ray Nicholson) is a stalker obsessed with hot-shot pop star Sofia Minor (Samara Weaving). We first meet him on the doorstep of Sofia’s mansion, her bodyguard Bell (Eric Dane) gently persuading Paul to cut his losses and go home. We can tell this has been going on for a while. Paul’s dressed up for the occasion (in a Moe Szyslak-esque wooing suit, complete with bow tie and a handful of posies) and grins with unwavering optimism.

Ray Nicholson is wisely cast (as he was in 2024’s Smile 2)—his arched eyebrows and easily coaxed grin are devilish, and here the inevitable comparisons will be drawn between the actor and his father, Jack Nicholson. But even if dropping the almost identically-faced younger Nicholson into horror and thriller films feels like a relatively cheap way to recreate the past, Ray Nicholson’s a clearly gifted actor in his own right, and here he’s forging his own path and his own performance style.

Paul, in Nicholson’s hands, is off-putting and creepy, as stalkers are wont to be. But he’s also dorky and embarrassing, with a touch of vulnerability. Nicholson’s refreshing in his eager naivety. Paul’s vaguely mentally unwell state leaves him in hallucinatory situations in which he sees whomever he’s speaking to as Sofia Minor, and that he and the singer are engaged to be married.

Nicholson is not angling for outright sympathy, but in playing Paul as hapless and truly, utterly deluded (and, it must be noted, sometimes murderous), he proceeds without any overarching maliciousness—mostly he can’t understand why everyone isn’t delighted to see him. After the doorstep altercation between Paul and Bell ends in bloodshed, Paul is sent to prison. But perhaps he isn’t as hapless as he seems, because six months into his stint, he escapes with quirky murderess jail pal, Penny (Alba Baptista). Along with J.H (Patrick Cox), his big bruiser of an accomplice, the trio set out once again for Sofia’s house, and a hopeful reconciliation.

Sofia Minor, as her astronomically themed name suggests, is a star who lives far from the real world, where real people live. In fact, Borderline sometimes feels as if it was filmed in total isolation, but this provides a sense of focus that is beneficial to a film that could so easily have spiralled into being broadly about fame. Instead, Borderline is just a sliver of the bigger picture, a microcosm of celebrity and entitlement.

Samara Weaving’s said her character was inspired by the likes of Britney Spears and Madonna, but while those seem like the obvious pulls, there’s something delightful about watching Weaving play in the shadows. Just as it’s unwise to trust a grinning man appearing at your doorstep, it’s equally foolish to trust a mega-celebrity, and much of Borderline can be spent trying to decipher Sofia’s motivations.

Rhodes (Jimmie Fails) is wondering the same. He’s the superstar basketball player shacking up with Sofia, who soon finds himself caught in the maelstrom that Paul and his friends bring with them. Weaving is effortlessly charismatic, but holds some mystery, some particular aloofness which we and Rhodes pick up on. He’s a sweet, gentle guy looking for a connection, but is he just another accessory for her public image?

Maybe it’s the delusion that all fans, stans, and arse-kissers suffer from: that we mean more to our idols than we actually do. Paul, Rhodes, and Bell are each within reason used for Sofia’s needs, for adoration, career advancement, and safety, respectively. But hasn’t this always been the deal? We watch our celebrities on TV or on cinema screens, we hear their voices from our radios and phones, they are the super-humans we are instructed to fall in love with… yet we understand the contract. Or at least we thought we did.

It’s an interesting choice to set Borderline during a time that had yet to see the absolute worst of rabid fandoms. Social media was years off, ‘Stan’ had not yet become a widely used term, and whether we cared about celebrities or not, there were long stretches of our days when we would not hear about them. It was possible, by virtue of not having a computer in our pockets at every hour of the day, to be blissfully out of the loop.

Yet it isn’t just access to celebrities—to total strangers—that’s most concerning. Rather, it’s the fact that we are being told that we are entitled to strangers that is horrifying. Implied in the constant stream of digital information about people, famous or otherwise, is that they belong to us, that this is their trade-off, their deal with the devil. Paul, and most rabid fans, won’t see it this way. It’ll be seen as passion, protectiveness—we’re just looking out for you. You pick a team and devote your life to fighting anyone who has a different team. It goes without saying that none of this is asked for.

In rocking up to her house in the middle of the night, Paul intends to marry—protect—Sofia. However, Borderline feel so narrow in its scope that Paul’s delusions appear to pop up from nowhere. Further blunting the satirical premise is the fact that regardless of fame, exposure, and access, Paul is nuts. It isn’t specified how exactly.

If Borderline had less of a winking sense of mischief then it might be more offensive. As it is, it’s a strange shock-absorber of a choice; how can the implicitness of Sofia, Bell, Rhodes—or any of us—be questioned when the big bad wolf would’ve come and blown the house down anyway? It certainly loosens up Nicholson, and the film at large, but we are let off the hook as a result. It’s nobody’s fault if there’s the occasional bad egg.

‘Parasocial relationships’ have become a buzzy topic over the last few years, yet Paul’s delusions might’ve meant he targeted anyone—it isn’t only celebs who accrue stalkers. If Borderline doesn’t end up having that much to say about how celebrity obsession develops (the film begins after the obsession is well underway) then at least it has some fun in the process, and doesn’t get bogged down in tiresome backstories.

The film’s modest first half is served by a wilder second half, in which the quirks Warden peppers throughout the film spill over into outright mayhem. Weaving is by now an absolute pro at playing tough-gal in survivor mode, and her utter weight-of-the-world, get-me-the-fuck-out-of-here scowl is never better than when Paul and co. lock her away inside her recording booth. It’s when Nicholson and Weaving finally interact that the sparks fly, their clashing energies threatening a combustion.

Add into the mix Alba Baptista, who as maniacal Penny almost steals the show with her mime-like, hyper-violent (yet oddly delightful) display, and Borderline is up and running. Warden lets the needle drops fly, his camera becomes unchained, and the heretofore pedestrian direction feels alive—as Penny jams a rolled-up magazine into a victim’s throat, it becomes clear that when all is said and done, Warden just wants to have a bit of chaotic fun.

An uneven third act threatens to bungle the burgeoning chemistry and carnage, with Weaving and Nicholson kept apart and Paul’s delusions once again taking centre stage. There’s something approaching progressive (or at least interesting) about Paul’s particular hallucinations, and the lack of gender distinction in them.

Earlier in the film, we see Rhodes dressed in Sofia’s clothes—he seems a bit embarrassed explaining it to Bell. And at the denouement, when Paul is in the throes of his delusion, Rhodes is standing at the altar, clad in a full bridal gown, Paul believing him to be Sofia.

Warden has some fun with gender and sexuality here, but it’s played with an earnestness that never feels as if it’s trying to shock. Instead, Paul takes to anyone that he sees as Sofia, which, while lessening the impact of his ‘relationship’ with her, suggests that it really isn’t about Sofia at all.

If Bjork had never become famous, would her real-life stalker, who mailed her sulphuric acid in 1996, have found another target of obsession? If all social media went down today, if ‘stans’ never again had access to Taylor or Chappell or Ariana, would they find new hobbies, or supplant the obsession with real-life targets?

Borderline, though unlikely to become your new obsession, is a spirited film that suggests that it doesn’t matter what our favourite person does, creates, or says—it doesn’t even matter who they are—once the feelings have taken hold, those deep, personal feelings, so like those in a romantic relationship, that is what we have fallen in love with, become enamoured with. The subject of affection can never be a real person after that, can never match up to the images we hold of them. We may not all go as far as the people in Borderline, but the sentiment is there, and instantly recognisable: you changed my life, now you are responsible for it.

USA | 2025 | 95 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Jimmy Warden.

starring: Samara Weaving, Ray Nicholson, Jimmie Fails, Alba Baptista & Eric Dane.