RASHOMON (1950)

The rape of a bride and the murder of her samurai husband are recalled from the perspectives of a bandit, the bride, the samurai's ghost and a woodcutter.

The rape of a bride and the murder of her samurai husband are recalled from the perspectives of a bandit, the bride, the samurai's ghost and a woodcutter.

Among other hyperboles, it’s been said that Rashomon / 羅生門 isn’t only the greatest film to come out of Japan, but perhaps the greatest ever made. While such claims are as debatable as the film’s own elusive narrative, it cannot be denied that it’s a hugely important work of pure cinema that changed the trajectory of Japan’s domestic film industry and established Akira Kurosawa among the pantheon of truly great directors. It’s also an effective and engrossing murder mystery, courtroom drama, supernatural horror, period piece, political satire, and philosophical conundrum. Even now, 75 years later, it has plenty to please and perturb everyone.

Rashomon was the name of a grand gatehouse. It was two storeys high, roofed with gilded tiles, and the entire structure comprised several flights of stairs and a stone bridge. On the first day of 1107, Masami Taira utilised it as a triumphal arch on his return to Kyoto after defeating Yoshichika Minamoto’s rival clan. As the Heian Era drew to a close, so the gate fell into disrepair and disrepute. It’s probably during this time that it became associated with some frightening folklore as it was used as a ‘base camp’ for outlaws and a cemetery of sorts, with corpses offered to the sky on its roof instead of being buried in times of plague and famine. The bodies on the roof are mentioned in the film’s dialogue.

According to tales told as early as the 10th-century, the demonic Oni Ibaraki-dōji rampaged through Kyoto and haunted the Rashomon gate until battled and driven out by the legendary samurai Watanabe no Tsuna. The script also drops a passing reference to this well-known story.

The respected author Ryūnosuke Akutagawa used Rashomon Gate as a motif in his short story, “In a Grove” / “藪の中”. The source material for Kurosawa’s film, it was first published in the January 1922 edition of the literary magazine Shinchō / 新潮. The existence of the gate fixes the events described within its 12th-century period setting while also serving a symbolic function as something that may be imagined but not seen. No trace of the gate remains, not even a single foundation stone. All we know of its existence comes from surviving plans, prints, historical accounts, folklore, and spooky stories. A simple monument erected in 1895 marks the place where it once stood, which is now a small play park. The site’s supernatural associations prevent town planners from approving any new build there. Sounds like an ideal premise for a J-Horror film, doesn’t it? And, in some ways, the film Rashomon can be approached as such.

A prominent theme running through “In a Grove”, and consequently Rashomon, is that many things we may know about or believe are not built upon one’s own primary experiences but gleaned from stories recounted by others. Much of the information that reaches us has, therefore, been mediated, coloured by the understanding of others or even deliberately selected and reframed to serve their own agenda, with the intent to influence others. This notion is like Friedrich Nietzsche’s critique of truth, in which he posits that our understanding of the world is based on subjective interpretations, and recognising the lies we tell reveals more of an underlying reality than anything presented as an objective ‘truth’, which he argued did not exist.

We may know where Rashomon Gate stood, but no one has lived experience of it, and we can only try to understand why it was built and what happened there via secondary sources. We may believe the historical fact that samurai Lord Masami Taira paraded victoriously through it after a decisive battle. Fewer will believe that another lord, Watanabe no Tsuna, fought and repelled a formidable Oni there. But which makes for the better story?

The newbie scriptwriter Shinobu Hashimoto thought “In a Grove” was a superb story and set himself the challenge of transcribing such a quintessentially literary work into audio-visual media. The story deals with the aftermath of a double crime in which a samurai has been murdered and his wife raped. We aren’t given a direct account of the crimes, and even if we were, they’d still be a fiction told by the author. Instead, we hear from several different ‘unreliable narrators’ who recount their perception of events leading up to the crimes. The testimonies of those directly involved are also presented: the notorious bandit Tajōmaru (Toshirô Mifune) who confesses; the raped woman Masako (Machiko Kyô); and even the dead man (Masayuki Mori) by way of a supernatural scene involving a shaman (Noriko Honma). Aspects in each of these accounts are in conflict, rendering it impossible to work out what actually occurred, calling into question the very notion of an objective truth.

Akira Kurosawa saw an early draft of the script while on the lookout for new material to pitch to Daiei Studios, which had invited him to direct for them following the success of The Quiet Duel / 静かなる決闘 (1949), a medical drama made by his own production company Eiga Geijutsu Kyōkai (Film Art Association), which Daiei had distributed. He worked with Shinobu Hashimoto on expanding and refining the screenplay, which would be the first of their eight successful collaborations.

Apparently, Kurosawa worked on his draft while staying at the same traditional Japanese inn, a ryokan in Atami, as Ishirō Honda, who was there scripting his debut feature, The Blue Pearl (1951). They both wrote all day and then met in the evening to read and give feedback on each other’s scripts, so in this way, Ishirō Honda had some uncredited input. He would become an equally important influence on the cinema of Japan as the writer-director of Godzilla (1954) and go on to direct genre classics such as The H-Man (1958), Battle in Outer Space (1959), and Mothra (1961), among many others.

Both Daiei and Toho considered and rejected the first Rashomon screenplay. So, Kurosawa simplified it and pitched it again, emphasising the meagre budgetary demands of a small cast of eight and just three locations. The Rashomon Gate itself was the only set that demanded any real production design and construction, with the other two being a woodland location and an outdoor courtyard with minimal props and costume. This time, Daiei recognised the potential.

The film opens with scenes of the Rashomon Gate, its name plaque serving as the title frame. The elements will play an important symbolic role throughout the film and, to start with, dirty rain hammers down, flowing off the roof in torrents and splashing up off the muddy road. The dilapidated gate is sheltering two morose men, a priest (Minoru Chiaki) sitting in silence and a woodcutter (Takashi Shimura) who mutters the first line of dialogue, “I don’t understand.” They are joined by a nameless third person, usually referred to as ‘the commoner’ (Kichijirô Ueda), who is absent from the original story and was constructed by Kurosawa to question the other two and propel the dialogue.

These three characters provide the framing device that contains the multi-layered, nested narrative in which we hear the testimony of several other characters. It’s easy to forget that all we see and hear of their stories is a visualisation of what is being recounted primarily by the woodcutter, who may or may not be recollecting correctly. Of course, he may choose to omit or embellish certain details. This isn’t the first film to show various constructs that may or may not have happened in the way we are shown, but it’s certainly the earliest to embrace such an unusual storytelling method as its raison d’être. It fully exploits and subverts the adage of ‘seeing is believing’ and reinforces the truism that ‘context is everything’. In this way, Kurosawa is not only exploring the concept of objective truth but also objective reality.

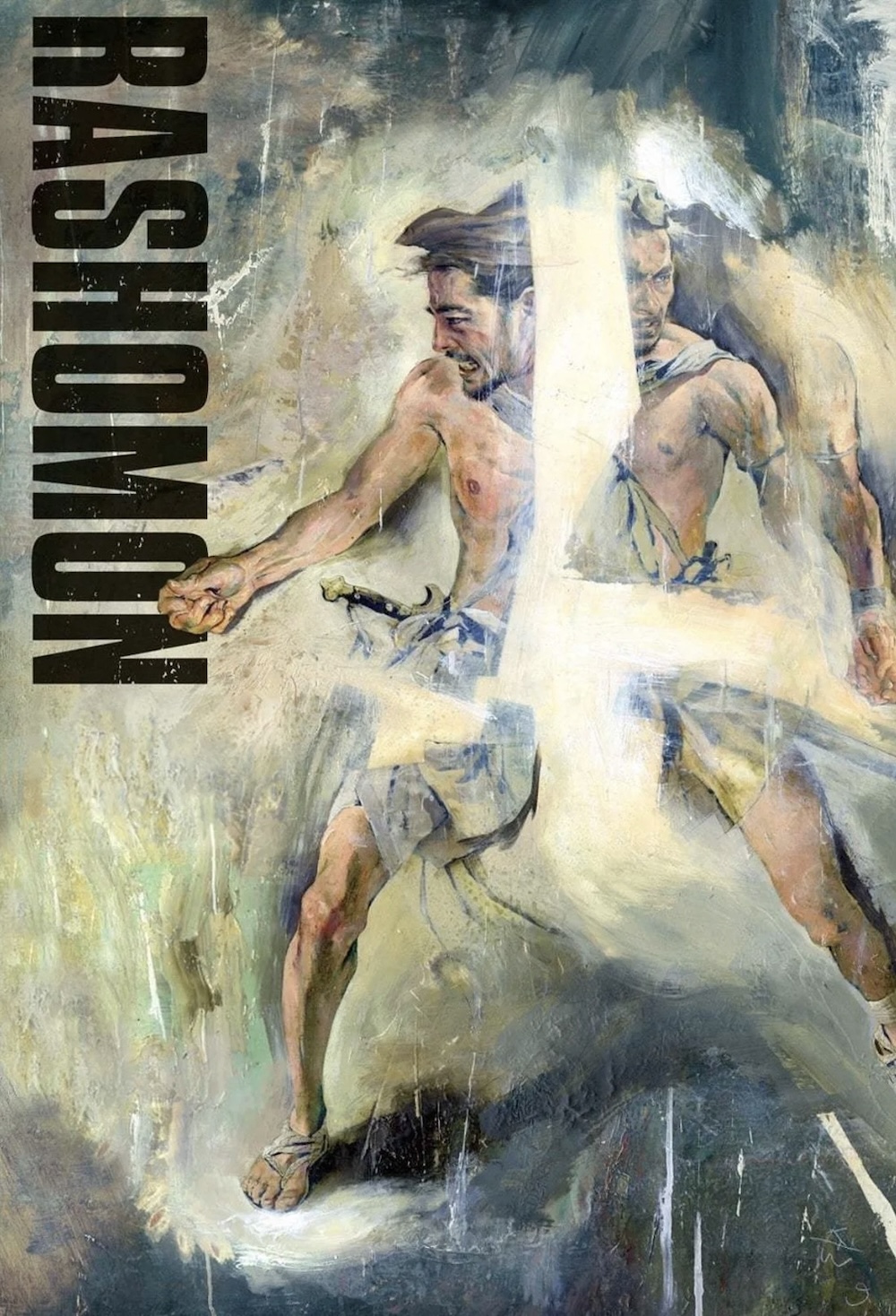

The acting is a treat with fine, carefully managed performances all round. Rashomon becomes a showcase for various acting styles with each vignette. Although it’s all very theatrical, it distances itself from stage traditions such as Noh and Kabuki. Instead, it features the Modern mannerist influence of the novelist and dramatist Tomoyoshi Murayama (Shinobi), who brought influences of Constructivism and German Expressionism back to Japan after studying art and theatre in Berlin during the interwar Weimar Republic. Indeed, the best way to describe Toshirô Mifune’s style here is Expressionistic, with some of his poses and facial expressions lifted from famous woodblock prints of warriors and bandits.

In the version of events as told by Tajômaru, he plays the bandit with cocksure arrogance as a formidable swordsman capable of defeating a samurai, and the rape is reframed, at least partly, as consensual. He struts and prowls like a wild beast. Kurosawa showed him wildlife documentaries about lions and great apes as he prepared. And even in his dishevelled state, he’s almost heroic. Later, in the version told by the woodcutter, he’s a sweaty bully and the sword fight is presented as almost comically incompetent and cowardly. It’s a towering performance from Mifune that confirmed him as one of the great actors of Japan, also drawing comparison to the likes of Marlon Brando and other contemporaries known for their unbridled onscreen energy.

The other performances are more than competent and, although imbued with great subtlety, may seem workmanlike by comparison. With the definite exception of relative newcomer Machiko Kyô, who is at least on a par and, in my opinion, surpasses Mifune in certain scenes. She portrays Masako on a spectrum ranging from fragile victim to a fierce independent woman who can turn the tables on the oppressive and abusive men who cannot tame her. But we must bear in mind that all the versions of events are being retold with a bias of masculinity, both within the fiction and through the male gaze of the lens.

Considering the limitations of lenses and cameras available at the time, the ambitious cinematography of Kazuo Miyagawa is astonishing. Texture, contrast, and depth of focus are used as narrative devices throughout. Sometimes, people are minimised in the distance while an important gesture or object is presented monumentally in the foreground. He manages to precisely realise each of Kurosawa’s meticulously composed shots and carefully scripted sequences. Apparently, the first reveal of Masako’s beauty, when her long veil is parted by the breeze as she rides her horse past the languid Tajōmaru, took a whole day of retakes to get right. There’s also deliberate use of triadic symmetry and asymmetry. Visual elements are arranged to create a sense of depth by presenting something in the foreground, middle distance, and background. This has been a tradition in Japanese art that tended to avoid vanishing point perspective until the later Edo period. In addition to this triadic approach, the three significant things either form a balanced or imbalanced triangular composition, thus echoing the harmony or disharmony between characters. The spatial relationships to each other change as the, often gendered, power gradients do.

Throughout, the abrupt cuts or conspicuous wipes make transitions obvious, emphasising that what we’re witnessing is a constructed representation as well as reflecting the disharmony or violence in the narrative. Only in the final scene does Kurosawa employ softer dissolves to visually integrate the action. The rain at the gate also ceases and the clouds part, allowing sunlight to break through on the sodden scene. This almost clichéd symbolism implies that, despite the darkness in the world and the great propensity for evil in humankind, there’s also a ray of hope. Even ‘bad’ people can choose to do good. A simple act of kindness can change the path that our own lives take and may have profound repercussions for others somewhere down the line. The closing scene, involving a foundling and a stolen kimono, and the title of the film itself, are not taken from the same story as the rest of the content but from Rashōmon / 羅生門, another short story by the same author, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa, first published in 1915.

It’s known that George Lucas took inspiration from Japan’s cinema in general and the films of Akira Kurosawa in particular. One clear influence that stands out in Star Wars (1977) is the prominent use of wipes for transitions, which had, at that time, fallen from favour. Rashomon has left an indelible legacy on world cinema and has been loosely reworked numerous times since. Quentin Tarantino cites it as a major inspiration for both Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Pulp Fiction (1994). Zhang Yimou’s international wuxia breakthrough, Hero (2002), shares many structural and narrative aspects. Over the decades, Rashomon has inspired episodes of popular television series from The Dick Van Dyke Show (1961-66) to Frasier (1993-2004), from Star Trek to Star Wars: The Acolyte (2023).

On its initial release, Rashomon was well-received in the domestic Japanese market, and although the box office figures are not reliable for this period, it reached the top ten. However, as Japan’s first entry to an international competition, it wasn’t the first choice until a panel of editors and directors from Film Italia strongly suggested that Rashomon represent Japan at the Venice Film Festival. It took home the Golden Lion, the first major international award to be won by a Japanese film. The president of Daiei, Masaichi Nagata, who had been dismissive of the film, soon changed his tune and realised the huge potential for the period dramas, which Daiei would soon become known for. However, Rashomon was rejected from competing at Cannes due to copyright concerns relating to its score, which quite obviously quotes Maurice Ravel’s Boléro, composed in 1928. Admittedly, I found this aspect of the film far too blatant and distracting—the only significant flaw in a near-perfect work.

The Rashomon Effect, or Principle, is a term now used in legal and psychology circles to describe the unreliability of eyewitness accounts. Immediately after experiencing anything in the ‘real world’, it enters memory where our perceptions of it are influenced by many factors, including preconceptions or prejudice constructed through our own past experiences. In addition to sensory limitations such as how clearly we saw or heard something, the emotional state of an individual will also impact their response to an experience and therefore affect how they later recall and interpret it. Witnesses to events will often give subtly, and not so subtly, differing versions of what they think happened. Some may well be lying to present things in ways that benefit them the most. Others may well believe they are giving an accurate account, although it can only ever be subjective.

Three-quarters of a century later, Rashomon remains essential viewing, not only for those with an interest in the cinema of Japan but for any serious cinephiles and aspiring filmmakers. However, it will be a different film for you than it was for me.

JAPAN | 1950 | 88 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

director: Akira Kurosawa.

writers: Akira Kurosawa & Shinobu Hashimoto (based on ‘In a Grove’ by Ryûnosuke Akutagawa).

starring: Toshiro Mifune, Masayuki Mori, Machiko Kyō, Takashi Shimura & Minoru Chiaki.